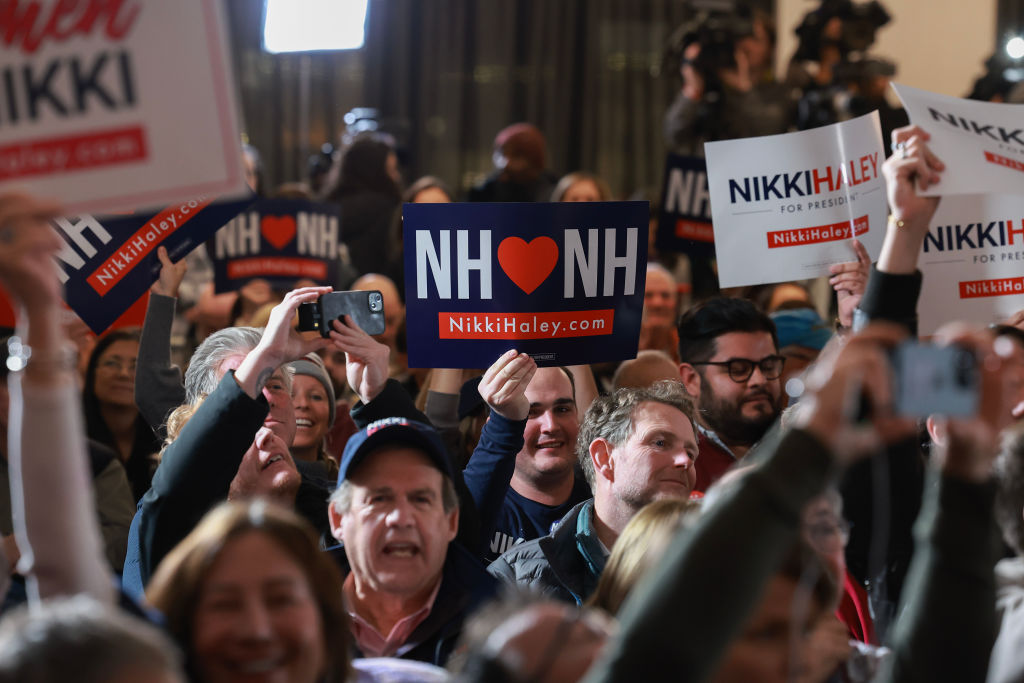

Donald Trump made noise in 2015 about running as an independent if he failed to clinch the Republican presidential nomination. This year, some have speculated that Nikki Haley could jump into the general election field with the gang at No Labels and mount a third party run against Trump and President Joe Biden.

So-called “sore loser laws” make such threats—if the goal is to win the presidency—highly unlikely. But if the goal is to spoil the election for others, there are more meaningful possibilities.

What are sore loser laws?

Sometimes known as “sour grapes” laws, sore loser restrictions keep failed primary election candidates, for local, state, and federal offices, from appearing on general election ballots—either as independents or with another party. Their rationale is that candidates should only get one shot per election cycle at a political office, meaning that if they take it and miss during the primary season they have to wait for another cycle.

These state laws, mostly passed between 1965 and 1985, take several forms. South Carolina bans the practice outright: “A person who was defeated as a candidate for nomination to an office in a party primary or party convention” cannot appear on the general election ballot unless the nominee dies or, for other reasons, is no longer the party’s nominee.

Georgia, like others, imposes restrictions against “cross-filing.” Candidates for a party nomination can neither declare for more than one party nor switch their status to independent in the same election cycle. So, a Republican could not compete for the GOP and Libertarian blessings at the same time. She also could not change to independent for the general election after losing the primary.

Montana has a “disaffiliation” requirement. To run for a party’s nomination, or as an independent, the candidate cannot have been “associated” with another party for a year before submitting paperwork to run for office. This association includes running for, or holding, political office as a member of that party. In Kansas, competing deadlines for filing as a candidate make it impossible for a primary loser to qualify for the general election as an independent or with another party.

In all, 47 states have significant restrictions on candidates running as independents or for other parties if they are failed primary candidates. But not all these laws would apply to presidential elections in the same way.

Do sore loser laws apply to presidential candidates?

The fact that presidential elections are national, with winners and losers declared at a convention outside the primary states, muddies the definitions within many sore loser laws. Presidential nominees often lose several primary contests within the same states they will run in for the general election. The timing of winning and losing is also variable. If a candidate suspends their campaign—effectively withdrawing from the race as Chris Christie did before the New Hampshire primary last month—but is still on the ballot, did they run in the state?

Since some state legislation does not make such distinctions or even reference presidential contests directly, it is not obvious how sore loser laws might apply collectively across the election and individually within some states.

Complicating the issue even more, some failed nomination contestants have shown up on general election ballots, even in states that bar the practice. In 1992, Lyndon LaRouche sought the Democratic nomination and lost. He ran as an independent that fall in Alabama, Arkansas, Minnesota, New Jersey, and elsewhere (and, interestingly, did so from prison).

This raises a thorny question: Does a state’s past decision to allow LaRouche mean it would have to allow Trump or Haley? LaRouche’s campaign was small potatoes, and it did not threaten to derail a major party candidate. The stakes would be much higher if Haley did something similar this year.

There are competing opinions on how this might unfold.

Ballot access expert Richard Winger thinks only two states—South Dakota and Texas—have sore loser laws that would unquestionably apply to presidential candidates. “Until 2012, no state ever perceived a sore-loser law to apply to presidential primaries,” Winger told Fox News last year. “That’s because it was always understood that in primaries people are voting for delegates to the national conventions, and in the general elections, voters are voting for presidential electors.” If he is correct, it is quite feasible for someone like Haley to compete until November, even if she loses the Republican nomination.

Attorneys Jason Torchinsky, Steve Roberts, Dennis Polio, and Andrew Pardue, writing in the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, disagree. They think “sore-loser laws in 28 states do indeed apply to presidential candidates” and those states would bar general election ballot access. Their analysis mostly discards past state actions, and they account for the many forms of sore loser laws noted above. They contend it would be impossible for someone who has already competed for the Republican nomination to run in the general and gain enough electoral college votes to win. Such a candidate could garner enough support to spoil another campaign or toss the contest into the U.S. House.

Inescapably, this would all be litigated.

What is the impact of sore loser laws?

In 2006, Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman lost the Democratic nomination for that office to Ned Lamont. Lieberman’s support for the Iraq War, and his moderate disposition, made him a ripe target. Connecticut did not have sore loser laws, so he ran in the general as the nominee for the “Connecticut for Lieberman Party” and won the three-candidate race. He gave moderates a voice. He also remained, for a time, one of the few senators willing to work across the aisle on legislation.

Lieberman’s story is instructive. There is reasonable evidence that sore loser laws promote party polarization, both within the electorate, and within legislative bodies. By removing the threat of an independent general election run by moderates, primary candidates can focus on the base of each party. While sore loser laws may have been passed to protect party leaders from the taste of sour grapes, the regulations have empowered the base in each camp. Successful candidates carry their narrow concerns for the base into office and behave accordingly. Compromise with the other party has become maybe the only unforgivable political sin.

There is a small movement to repeal sore loser laws, which would allow vanquished primary candidates into the general election. More importantly, repealing them might force other candidates to moderate in response to the potential of another contest against a candidate poised to get support from the larger, more diverse, pool of general election voters.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.