I am not really from a small town: The Lubbock metropolitan area—a phrase that makes me smile a little to write—is home to 328,283 people, right between Boulder, Colorado, and Green Bay, Wisconsin, in the population rankings. It feels smaller because it is isolated: the nearest big cities being Dallas and Fort Worth, 330 miles to the east, or Albuquerque, about the same distance to the west. Turn the axis a little bit, and Lubbock sits about halfway between Denver and Houston, neither of which is very close. It is a small city rather than a small town, and it has something in common with a lot of small cities and small towns: a crime rate that is three times that of New York City, almost twice that of Los Angeles, more than twice that of Boston or Laredo, about 80 percent higher than Las Vegas, higher than Dallas, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Atlanta, or Seattle.

Life in a big city, particularly a transit-oriented northeastern city such as New York, is public in a way that life in a small city—where everybody gets around in cars and the sidewalks are mostly empty—is not. On the street level, New York (or parts of New York) feels a lot more dangerous than, say, Odessa—the most dangerous city in Texas when it comes to violent crime and overall crime. Yet, in reality, that small Texas city has a crime rate per 100,000 that is similar to what you would find in the second tier of the most dangerous American cities (Detroit, Tulsa, Kansas City, Missouri). Though it is still short of the top tier of high-crime cities that includes St. Louis, Memphis, and Albuquerque, each of which has an overall crime rate more than four times that of New York City.

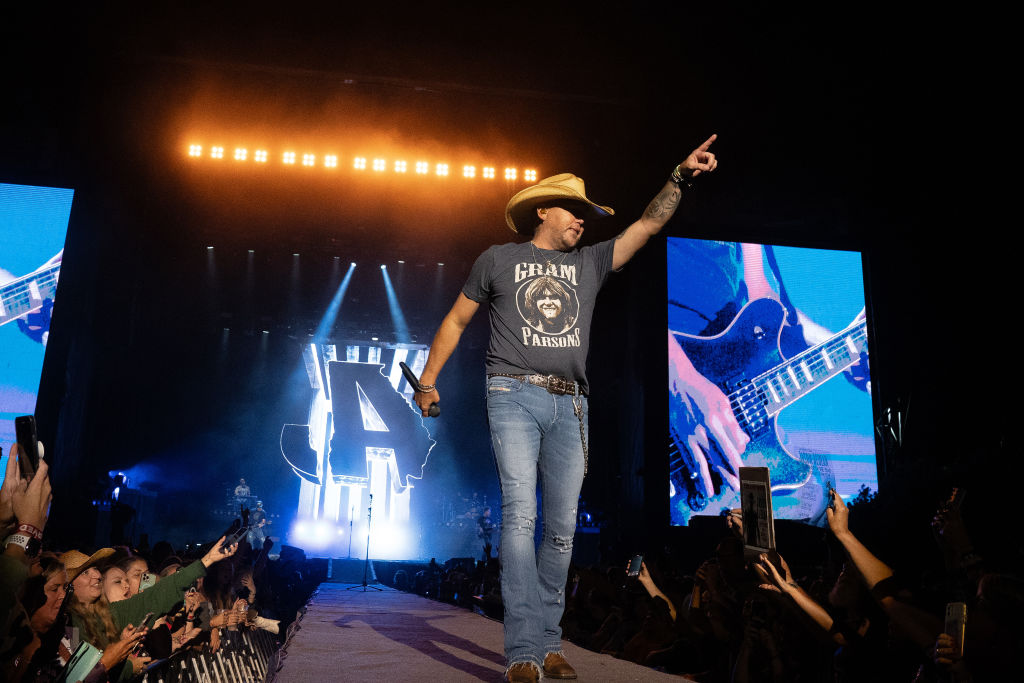

Jason Aldean, who has made a stink with his “Try That in a Small Town,” should think about spending some time in a small town. He might learn something. (If you missed it, the ruckus began with complaints that Aldean shot a video for the song near where a lynching had happened many years ago, though it isn’t clear that that horrible crime had anything to do with the site selection; the criticism later moved on to the generally vigilante-ish tone of the song.) Like so many of the self-appointed spokesmen for small towns and simple country folk, Aldean himself is nothing of the sort: He is, in fact, a former private-school kid from Macon, Georgia., metro population 420,693, adjacent to the greater Atlanta metropolis, population about 6.3 million. Macon, you may not be surprised at this point to learn, has a considerably higher crime rate than New York, Los Angeles, or Newark, New Jersey.

When it comes to actual small towns and rural areas, the data can be a little wonky—one ugly Saturday night in Muleshoe, Texas, can throw the numbers off for a whole year. But the data we do have do not support the hypothesis that life is safer in small towns: The aforementioned Muleshoe has had a higher-than-average crime rate in recent years. Homicides jumped 25 percent in rural areas in 2020. “It was like people lost their ever-lovin’ minds,” one small-town prosecutor told the Wall Street Journal.

Isolation correlates with certain kinds of crimes: Because the news is mostly written by college graduates, you probably have heard a great deal about sexual assault on college campuses; in reality, women in college are less likely to experience sexual assault than are women in the general population. There are high levels of sexual assault in isolated rural areas, on Indian reservations, and in Alaska, which has by far the nation’s highest rate of rape, more than twice that of Arkansas, which comes in second place. Sexual assault, like most violent crimes, tends to disproportionately affect people who are poor, who are not white, and who lack access to social capital. Crimes of domestic violence are, by some measures, much higher in rural areas than in big cities.

I don’t worry too much about Jason Aldean per se. Pop stars in our time are actors, either implicitly or explicitly. Ice-T, responding to a ninny who nettled him for making a living playing cops on television after making a pile of money from his “Cop Killer”-era music, gave the only sensible reply: “It’s both acting.” John J. Mellancamp didn’t hang around Seymour, Indiana, his whole life: He went to college and then went to New York and became Johnny Cougar. “I can breathe in a small town,” he sang, and the air is pretty nice in Montecito, California. Entertainers aren’t the characters they play—poor Jim Parsons apparently has to remind people that he isn’t a brilliant physicist—and I don’t begrudge Jason Aldean how he makes his money. But people who can’t tell the dog-and-pony show from the real world need to get off social media for a minute and read the damned news.

Critics such as my friend Kathryn Jean Lopez who have suggested that Aldean has perhaps struck the wrong tone in his song have, predictably, been subjected to a torrent of abuse from people who insist that they just don’t know what life is like in a small town. Maybe Kathryn, a daughter of Manhattan, doesn’t. But, then neither does Jason Aldean, apparently, and neither do those who embrace his righteous tough-guy posturing while in pristine ignorance of the actual facts of the case.

Proud to be an Okie from Muskogee, like Merle Haggard? Go be a beat cop in Muskogee, Oklahoma, for a couple of years, and you’ll be singing a different tune.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.