In the immortal words of the Count de Money, “The people are revolting.” (“You got that right,” replies the king. “They stink on ice.”) Nobody is happy about their property taxes.

I know I’m not.

(Part of my beef with my local property taxes is purely procedural, i.e., that the techno-incompetents who run my little semirural taxing jurisdiction have an online payment system that will not process a payment of more than $2,000, a sum that is ... a good bit less than my property taxes. It takes a special kind of municipal turd to raise taxes above what your payment system can handle.)

And while I’m feeling surly ...

Writing in Slate, which has no obvious editorial standards, Yale law professor David Schleicher offers some pretty interesting observations about California’s Proposition 13, the 1978 ballot measure that limited property tax increases in the state and that is regarded both as a precursor of the Ronald Reagan movement in 1980 and an inspiration for today’s property tax fights. Schleicher argues that limiting property tax assessment increases, as Georgia recently has done, distorts the market. “Changes like those just passed in Georgia slow the rate at which homes change hands by making new buyers and builders pay more in taxes than existing holders. This makes it harder for people to move to opportunity and punishes people for building new homes.”

So far, so good.

But:

In California, Schleicher writes, Proposition 13 “resulted in education spending cratering.” And that would be a very relevant consideration, if it were true. But it isn’t. It is the opposite of the truth. I know that Slate has no particular standards about what kind of expired baloney it will publish, but I like to believe that Yale professors still do. They should—we need them to.

As you might have guessed if you know anything about California, the state’s spending on the schools did not crater—or even decline—following the passage of Proposition 13. By the relevant measure—per-pupil spending in real dollars—California’s school spending went up by a big jump—about 25 percent—in the decade following Proposition 13’s being enacted. To reiterate: This is spending per student measured in inflation-adjusted dollars. So Consumer Price Index changes and student-population size are accounted for.

California spent a lot more money on education, both in nominal gross terms and in real per-student terms, after Prop 13 than it did before. Schleicher’s claim about education spending is untrue. (As of yesterday evening, the article remained uncorrected.) I will not relitigate the entire history of the media bias debate here except to note that it almost always is the case that unexamined, unquestioned, uncorrected falsehoods of this kind almost always support some progressive political priority. You can observe much the same thing in Slate’s utterly incompetent and error-ridden coverage of firearms policy or its ludicrous Supreme Court coverage. I don’t have a bee in my bonnet about this stuff because I think Prop 13 was great policy—I don’t; more on that below—but because the contempt that Slate and its editors show for journalism as an enterprise undermines the credibility of news media per se. The same is true across the press. I don’t want to see the Washington Post collapse—I want to see it competently edited. We need functional newspapers, even if the paper bit is going away.

Back to California.

What actually happened is that many other states increased their education spending even more quickly than California did—by a national average of around 30 percent to California’s 25 percent. The result is that over some years California went from being one of the relatively high-spending states to one of the relatively low-spending states—but that is an interstate comparison, not a California-to-California comparison. Education spending did not crater in California—or in the rest of the country. In real per-student terms, education spending has been going up, up, up for practically all of my life.

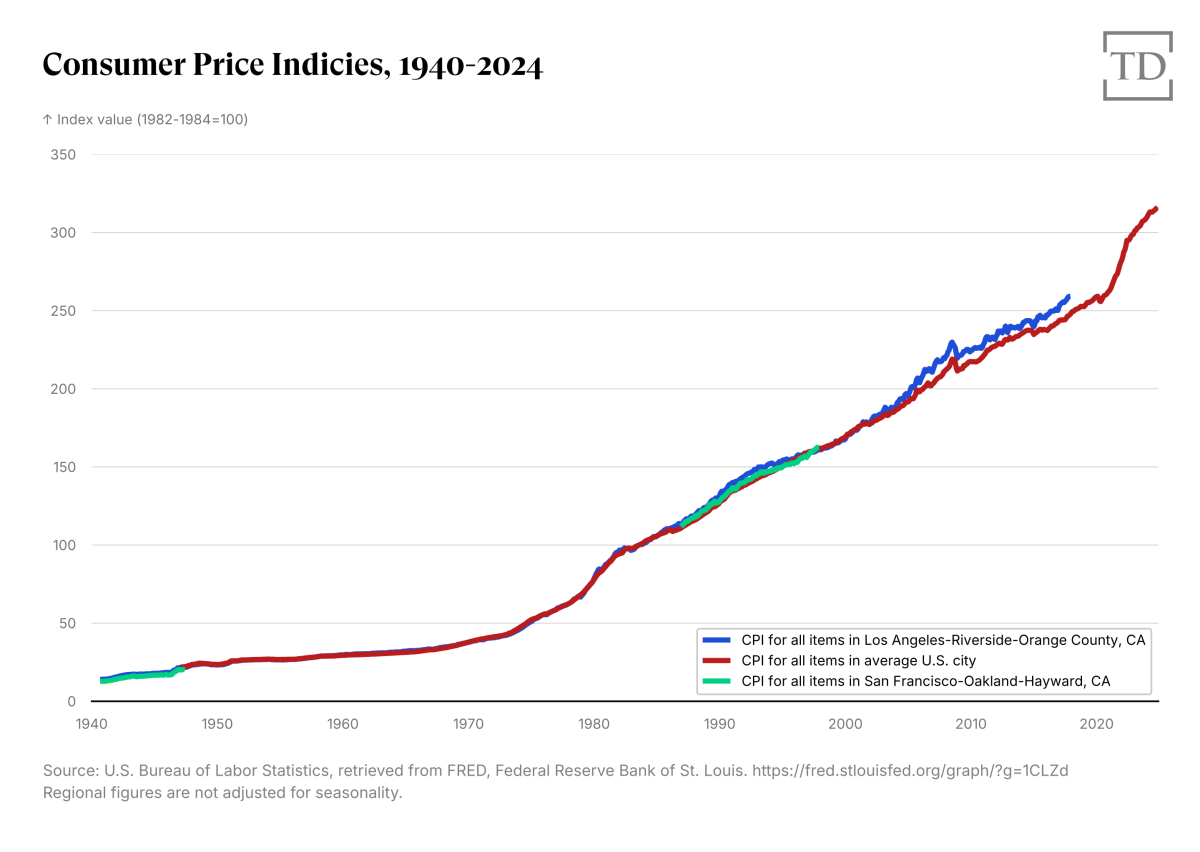

I wrote to Schleicher to see whether I was missing something, and his answer was unsatisfactory. He pointed to the interstate comparison as though that had something to do with what he actually wrote—which it doesn't—and then added that California has experienced bigger cost-of-living increases than the rest of the country, so maybe those CPI-adjusted figures don’t tell the whole story. But that doesn’t account for the economic facts, either. Note here that the data for San Francisco are limited, but here is a comparison between urban-U.S. CPI and CPI in the Los Angeles and San Francisco metros by my buddy FRED, aka Federal Reserve Economic Data:

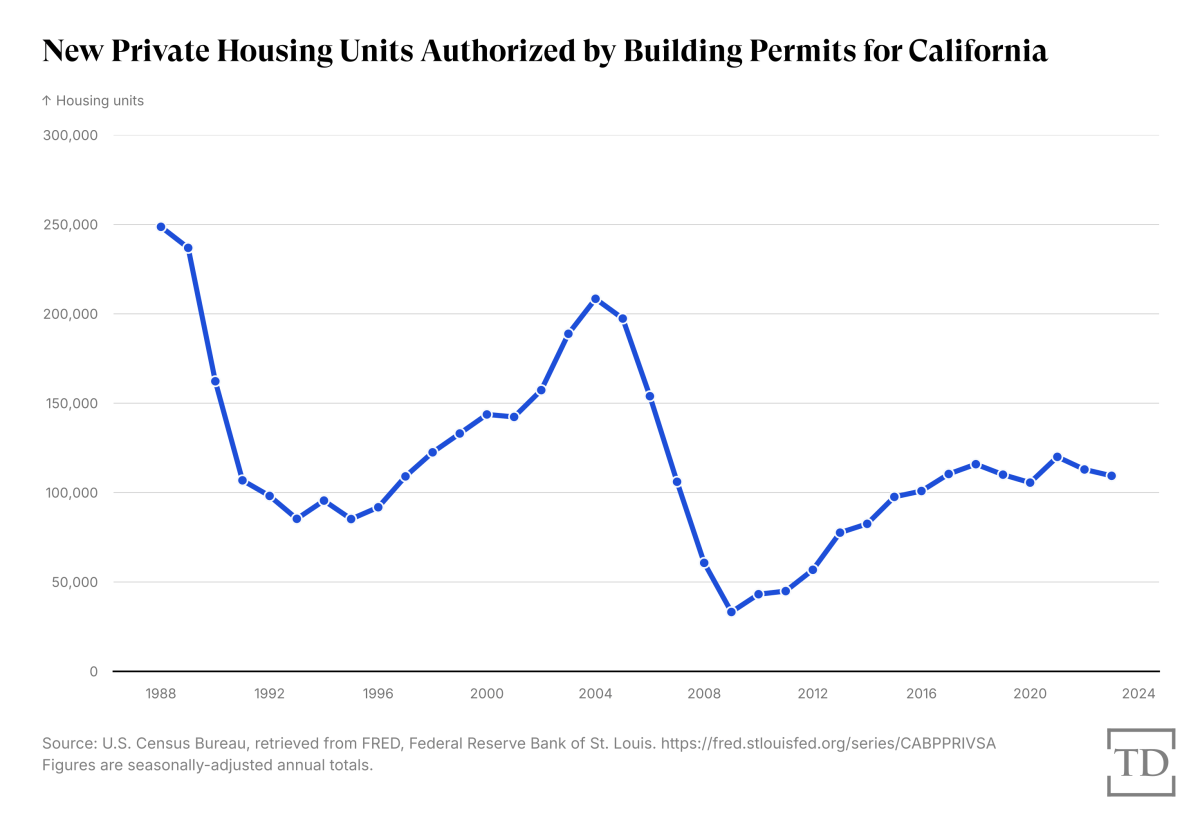

Not exactly a radical departure. But FRED does have some ideas about why the housing market in California isn’t so great:

Prof. Schleicher may be very well correct about the effect of the tax disincentives at work, but there is a steady build-up in permit approvals from 1994-2004 and then a sharp downturn from which California still has not recovered.

If you go back and read post-Prop 13 media reports in California, you’ll see a lot of stories about highly valued programs that are being cut or reduced, administrators complaining about the financial pinch, all that kind of thing. Assuming that the reporters weren’t simply making up stories about course offerings being reduced or library hours being cut, we have a mystery: More money was being spent, but things people care about were being cut.

So, where did the money go?

The answer, in no small part, is administrative costs. I do not have California-specific figures, but, to give you an indicator of the wider school-spending context: Nationally, we saw total school-level administration costs per student climb about 42 percent, and administration salaries per student increase by about 24 percent from 1990-91 to 2019-20. That’s according to the National Center for Education Statistics, a project of the U.S. Department of Education. On a per-student basis (meaning that the spending growth isn’t driven by population growth) spending on school administrator benefits has more than doubled, money spent on purchased services has doubled, etc. That’s larger than the increase in instructional expenditures (which includes salaries and benefits for instructional staff) while spending on textbooks has declined. So, the money isn’t going to books, and, while some of it is going to salaries and benefits for teachers, it is disproportionately going to administrative costs. There are lots of things that drive that: bureaucratic bloat, increasing compliance costs from heavier regulation, the gradual transformation of the schools into more general social-welfare agencies (we’ve seen large increases in real per-student food services spending), etc.

So, the real story reads more like this: After Proposition 13, education spending in California increased substantially, though not as quickly as in the rest of the country, but we have reason to believe that the increases were disproportionately captured by political interests who put that extra money toward the creation of new administrative jobs and increased compensation for existing ones, thereby servicing an important political constituency, while state and federal political interests successfully shifted some obligations (on food support, for example) away from their budgets and onto the schools’ budgets. And wherever the additional money went, it wasn’t for old-fashioned stuff like, you know, books. And the results have been ... not great.

It is worth pointing out here that the failure of Prop 13 is not a failure of mushy-headed Californian progressivism but a failure of conventional conservative orthodoxy: Prop 13 was an early example of bog-standard Republican “starve the beast” thinking. As it turns out, the beast wasn’t starved: Prop 13 created a bunch of market distortions, but spending was not reduced, or even slowed down significantly as far as the data can show. I am not an enthusiast for “starve the beast”-ism for the same reason I am not an enthusiast for using business regulations to achieve social-welfare ends: It is cowardly.

As I have written many times before, we talk about civic virtue in politics as though it were some ethereal, metaphysical thing with no practical application for hard-headed realists of the kind that Republicans like to flatter themselves as being. Civic virtue is eminently practical: Maladministration in public programs, like bias in media, undermines public confidence in critical institutions, and that makes public life more expensive and more dysfunctional. Trust, on the other hand, enables us to lower all sorts of transaction costs. “Starve-the-beast”-ism is cowardly in that its advocates champion the popular stuff—tax cuts!—right now, and then claim that this will force ... somebody else ... to do the hard and unpopular stuff—reducing spending—at some point in the future. Beyond being utterly chickens—t, there is the inconvenient fact that it almost never works. Even if you were a completely amoral political operator who just wanted to get a few useful things done, you still would ultimately need to take into account that the cowardly approach is generally ineffective.

We need politicians—and news media and Ivy League intellectuals—who can and will tell us the truth about things. Our problems are too deep and too complex to address in any other way.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.