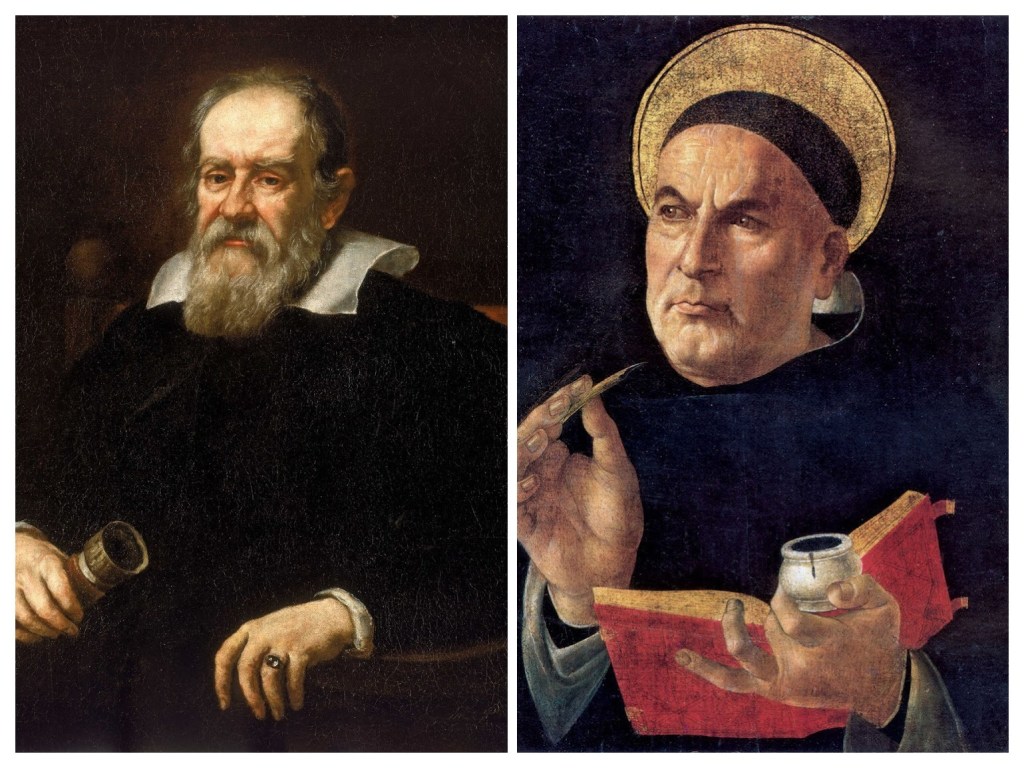

The prestige of the scientific revolution goes largely unquestioned. The power of its discoveries, the usefulness of its results, the speed of its progress all win approval when compared to the ancient worldview that preceded it. But despite modern characterizations, the ancient view—especially as articulated by Aristotle—was and remains broader than its modern counterpart. Modern science may be more productive and accurate, yet it eschews the philosophical resources to ground and measure its significant achievements. Two titans of the Western canon, Galileo and Thomas Aquinas, help illustrate the point.

Galileo is best known for the groundbreaking discoveries he achieved with his telescope. Through what was then a remarkably new observational instrument, he helped to topple the long-held geocentric view of the universe in favor of the heliocentric alternative. The former view was largely understood in terms of Aristotle’s four causes: material, formal, efficient, and final. Materially, the celestial bodies were characterized as being composed of a different stuff, which accounted for their distinct movement; the efficient cause of their movement was their attraction to the outermost sphere, that of the unmoved mover; their formal cause was their movement in perfect circles befitting eternal bodies; their final cause was their relation to the unmoved mover.

The intellectual revolution that Galileo contributed to changed all this. It held celestial bodies were made of matter, just like the earth; the efficient cause of their movement was neither an outer sphere nor the earth, but rather the sun, which has no privileged location; the form of their movement was governed by the same laws that govern all movements, even of earthly things; and the final cause of celestial movement, as with modern science generally, was considerably less central or altogether ignored.

There are some key assumptions behind Galileo’s philosophy. In his essay The Assayer, published 400 years ago on October 1623, Galileo lays out the details of his epistemology. He focuses on the senses, the first element of our cognition, almost exclusively through material and efficient causes. Invoking one of the basic claims of atomism—an ancient philosophy dating from the fifth and fourth centuries BCE—he regards all material entities to be collections of tiny particles, which he calls “corpuscles.” Galileo then claims that our sensations are explained not by objects, but by the qualities of the object’s corpuscles. Something might taste pleasant or harsh, for example, because of the shape of the corpuscles as they contact the tongue (smooth or jagged respectively). Next, he develops the distinction between primary and secondary qualities. He deemed that primary qualities (ex: size, shape, and motion) truly belong to corpuscles, and by their conglomeration, the objects they compose. By contrast, we impute secondary qualities, which we derive from our senses, onto objects because of their effect on our sensory organs.

Even as he departs from Aristotle’s philosophy in this initial step of the scientific revolution, Galileo still invokes some of its components. He explicitly associates one of Aristotle’s earthly elements with one of our external senses: earth with touch because of its solidity, smell with fire because of how it rises through the atmosphere, savoriness with water which is a characteristic in the function of taste, and air with hearing understood as vibrations thereof. Galileo leaves sight, which he concedes to be “the most excellent and noble of all the senses,” largely unexplained.

It’s an avowedly materialist approach. All senses, insofar as they are explicable, are explained by the efficient causality of material elements (the corpuscles) on passive material receptors (the sensory organs).

But as plausible as this might seem to us today, Galileo’s approach raises significant concerns about our cognition. Something important is lost when sensory knowledge is construed as simply the passive reception of physical stimuli, when it omits an active response in sensate beings.

That’s something that Thomas Aquinas, the 13th century philosopher and Catholic saint, understood. Perhaps to our modern surprise, his philosophy helps support a careful analysis of Galileo’s project: It proceeds along the same lines, associating four external senses with the same earthly element. But he does so in a way that is much closer to Aristotle’s epistemology.

To each sensory faculty, Aquinas identifies a spiritual or supraphysical component, which emphasizes an active response by the senses. When a sense organ registers some quality, it “becomes” that quality in a manner that is of the physical but is not itself physical. When the eye sees the color blue, it can be said to “become” blue, not materially, but in intention. The eye actively apprehends blue rather than simply receiving its influence. This markedly differs from the material passivity of sensation proposed by Galileo. For him, colors, audible sounds, tactile qualities, are received without any cognitive apprehension. Aristotle and Aquinas, by contrast, make clear that sensation properly understood involves a kind of responsiveness to stimuli, and that sense organs are not found in isolation, but rather that they necessarily belong to cognitive agents.

For both of these interpreters of Aristotle, sight poses particular difficulties. Galileo, granting its uniqueness, seeming to have run out of earthly elements by which to explain it, declines to go further. Aquinas, on the other hand, characterizes it entirely by supraphysical change. In our times, biological research explains sight in terms of rods and cones: retinal photoreceptors that register different kinds of light, dim and bright respectively. This answer, of course, is still open to different interpretations. Galileo might well appreciate that these photoreceptors may be characterized as purely physical, thus providing the explanation to complete his study. Aquinas, by contrast, would still insist that such reception must be apprehended for it to count as more than physical change, something we must assess in terms of formal and final causality.

The advantage of Aquinas’ reading is that it locates sensation within a broader cognitive rubric which involves perception in all animals, and which in humans includes intellection or cognition. Cognition in this broader sense is not just an agent’s awareness that it’s being effected by stimuli; it includes the recognition of the object that causes this. Sheep scurry away from an approaching odor, not simply because of its offensiveness, but because they associate it with a threatening wolf, the formal object of such sensation. The final cause, or end, of this apprehension is the sheep’s own safety. It’s similar with humans, though in more varied and complex ways. Unique to humans is our desire to know what a thing is, not just as pertaining to our use or harm, but as pertaining to the thing itself: What is it in itself? Sensation certainly begins such engagements, but it does not complete it.

Evidence of final causality in human knowledge can even be gathered in Galileo’s astronomical investigations. We not only see light (matter), we see points of light in the sky, which we understand to be planets and stars (form) derived from the objects causing such cognition (efficient cause). In this we invariably seek to understand such phenomena according to some ultimate end (final cause). In Galileo’s case this is the dynamic patterns of those objects relative to each other. For Aquinas it’s the relation of such movement relative to more theological considerations.

Aristotle began his Metaphysics with the observation “all men desire to know, and the evidence of this is the delight they take in their senses.” This delight is not simply in sensation, but in how sensation beckons us to understand the world and ourselves. Perhaps this knowledge allows us to appreciate our relation to God in a direct physical manner, or perhaps not, but that’s another question: In either case, while this end begins with sensation, it stretches far beyond it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.