Last week, Ruby Freeman and Wandrea “Shaye” Moss, two Fulton County, Georgia, election workers, filed a defamation lawsuit against The Gateway Pundit, and its publisher Jim Hoft and contributor Joe Hoft.

The right-wing media company, which has a history of promoting falsehoods, had specifically targeted both Freeman, a temporary election worker during the 2020 election, and her daughter, Moss, a Fulton County registration officer, with false claims. The suit includes chilling details showing how the misinformation campaign made both women fear for their lives.

And in response? The Gateway Pundit published a story doubling down on the very same claims that brought about the suit in the first place.

On December 2, the site published a story headlined “Ruby Freeman and Daughter Sue Gateway Pundit for Posting Video of Her Shoving Ballots Through Voting Machines Numerous Times – PLEASE HELP US Fight This Latest Lawsuit.”

The Gateway Pundit, according to the lawsuit, had more than 2.8 million unique visitors in September 2021. Comscore shows it having 3.2 million uniques in October 2021 making it the 11th most visited conservative website in the U.S. It was one of the foremost purveyors of false claims about the 2020 election, not just in regards to Georgia. It spread false claims about Dominion Voting Systems, Michigan’s election results, Maricopa County, Arizona; and other issues. And so the case highlights not only the dangers of misinformation and disinformation, but also the difficulty in trying to tamp it down that through reporting and fact checking.

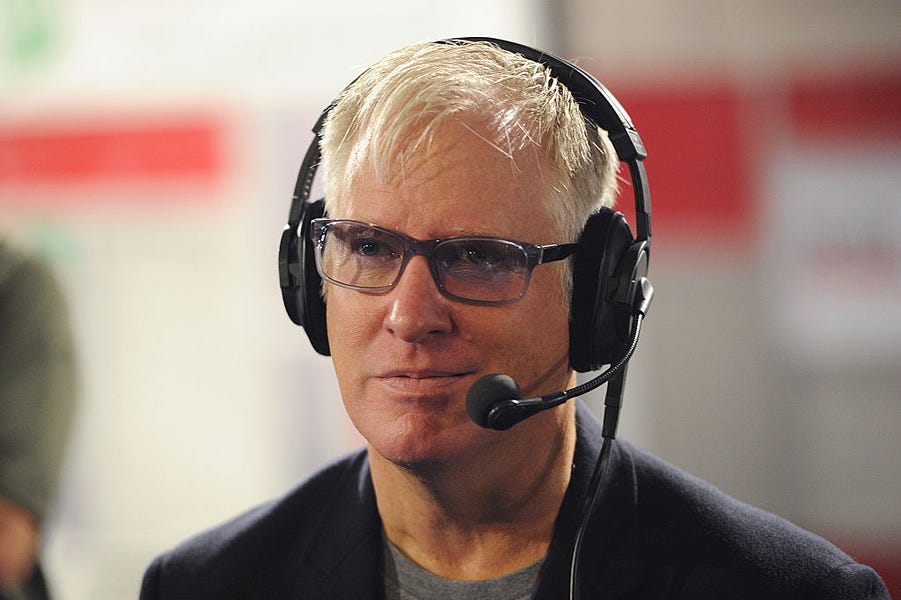

Bill Adair, founder of PolitiFact and a professor of journalism and public policy at Duke University, said that although the increasingly large partisan divide is not insurmountable, it has become harder to convince some audiences of facts when their favorite politician says something false.

“What’s most troubling to me is when certain audiences just resist facts and that has become a real problem in our political discourse, particularly critical issues such as vaccines and voting,” said Adair. “Those issues are so rampant with misinformation, it worries me that accurate information is not getting through.”

The importance of fact checking, explained Adair, is that, even if readers aren’t convinced that a fact check is debunking misinformation, the fact checker is still creating a larger record of falsehoods from a particular politician or news organization.

“Anytime a claim is getting a wide audience, unless it’s clearly satire, I think it’s valuable to fact check it,” he said. “I think it needs to be logged in so that, one, the people who might go to that source see what that source is saying and see that that source has said something false, but also to create the larger record that tells people that a particular news organization has a record for many falsehoods.”

David Becker, the executive director and founder of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research, thinks that although holding organizations like the Gateway Pundit accountable is a good step, it won’t solve the issue entirely.

“There are way too many people whose entire model of income and wealth is built upon generating disinformation that hurts people,” Becker said. “The grifters that are behind The Gateway Pundit will likely just find another way to spread disinformation after it’s gone. I think we need to hold individuals and organizations who create this content and spread it accountable. And that’s just one step in a very, very long road to getting back to reality.”

In Becker’s eyes, it’s not just Freeman and Moss who are victims, but to a different degree and in a completely different way, the people who read The Gateway Pundit’s lies are victims, too. “We need to have empathy for them,” he says. “They’re being targeted as part of a profit-making scam.”

In the lawsuit, which was filed in circuit court in St. Louis, Freeman and Moss claim that The Gateway Pundit’s lies have not only “devastated their personal and professional reputations,” but have also “instigated a deluge of intimidation, harassment, and threats that has forced them to change their phone numbers, delete their online accounts, and fear for their physical safety.”

Here’s how it all started.

At a Georgia Senate hearing on December 3, 2020, a member of Trump’s legal team presented a video clip that supposedly showed video footage from Election Night of Fulton County election workers bringing in thousands of illegal ballots in what was described as suspicious “suitcases.” The conspiracy posited that the “illegal ballots” were counted without Republican poll observers present.

The claim soon began circulating in pro-Trump spheres. Jenna Ellis, a legal adviser for Trump, tweeted that the video was “SHOCKING”:

That same day, The Gateway Pundit published the first of several stories circulating the same rumor. The story, the first to explicitly name Freeman, is headlined: “What’s Up, Ruby?… BREAKING: Crooked Operative Filmed Pulling Out Suitcases of Ballots in Georgia IS IDENTIFIED.” The article alleges Freeman was “one of those people involved who were caught on video counting illegal ballots from a suitcase stashed under a table.”

On December 4, The Gateway Pundit published a second story, naming Freeman’s daughter, Moss. The story was published with a similar headline: “BREAKING: CROOKED GEORGIA ELECTIONS SUPERVISER [sic] Filmed Pulling Out Suitcases of Ballots from Beneath Table IS IDENTIFIED — IT’S RUBY’S DAUGHTER! (Video).”

The rumors of suitcases filled with fraudulent ballots in Fulton County were false and were quickly debunked by election officials. Gabriel Sterling, Georgia’s voting implementation manager and a Republican, appeared on The Dispatch Podcast that same day and said that the containers described as suspicious “suitcases” were actually the “carrying cases used in dozens of counties to haul around ballots so you don’t have to be carrying boxes. They have wheels on them,” he said. Fulton County officials also addressed the “rampant misinformation” the same day the story naming Moss was published, tweeting that “we are aware of no credible reports of voter fraud in Fulton County.”

Sterling further debunked the conspiracy during a December 7 press conference: “The ‘secret suitcases with magic ballots’ were actually ballots that had been packed into those absentee ballot carriers by the workers in plain view of the monitors and the press,” said Sterling. “The reason they were packed away is because they were under the misbegotten impression that they were getting to go home.”

Trump not only repeated the false claim about suitcases during his January 3 phone call with Raffensperger, where he pleaded with Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to overturn the results of the election, but he also mentioned Freeman by name 18 times.

During the call, Trump referenced a video that he claimed proved there was a “water break” that caused law enforcement and Republican poll watchers to flee the area. Trump further explained that there were 18,000 fraudulent ballots “all for Biden” in “what looked to be suitcases or trunks, suitcases but they weren’t in voter boxes.”

The Dispatch’s Alec Dent addressed this false claim in a fact check from December 24: “Georgia’s voting implementation manager, Gabriel Sterling, has said that no poll watchers were forced to leave the room. Surveillance footage shows that a water leak did occur, but Trump appears to be conflating two separate incidents. The leak occurred around 6 a.m. on November 3, while the video Trump describes happened around 10:15 p.m. November 3. Sterling says that the poll watchers and the poll workers left out of confusion over what time they were allowed to stop. The poll workers returned after being informed of their mistake, and the poll watchers returned about 80 minutes later.”

Although the rumors were false, Freeman and Moss were quickly subjected to threats and harassment. Freeman, as noted in the lawsuit, fled her home for two months at the recommendation of the FBI. “On January 6, 2021, a crowd surrounded Ms. Freeman’s house, some on foot, some in vehicles, others equipped with a bullhorn. Fortunately, Ms. Freeman had followed the FBI’s advice and had temporarily relocated from her home,” the lawsuit notes.

The suit also details how, as a result of the harassment, Freeman and Moss are both fearful when they are recognized in public. Freeman was forced to give up her online business when social media became too difficult to navigate, and Moss suffered in her work as a Fulton County elections official.

Freeman, the lawsuit notes, at one point got 75 text messages and 420 emails, with one message in particular that said: “‘We know where you live, we coming to get you.’”

Moss used to live with her grandmother, and there were at least two times that strangers showed up at the grandmother’s home and “attempted to push into the house in order to make a ‘citizens’ arrest.’” People would also frequently send unwanted pizzas to Moss’s grandmother’s house.

“I couldn’t have imagined the lies that The Gateway Pundit would tell about me, pushing people to harass me and my family and to threaten us with violence,” Freeman said in a statement from Protect Democracy, which is part of the legal team representing Freeman and Moss. “I want the defendants to know that my daughter and I are real people who deserve justice, and I never want them to do this to anyone else.”

Jim Hoft did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Freeman and Moss are being represented by Protect Democracy with DuBose Miller LLC, Dowd Bennett LLP, and Kastorf Law, LLC and the Yale Law School’s Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic.

Brittany Williams, Counsel at Protect Democracy, in an email to The Dispatch, explained how the lies documented in the lawsuit impact democracy more broadly.

“The Gateway Pundit has an outsized reach and platform. The defendants speak to millions of people and their stories are shared and amplified across our information ecosystem,” Williams said. “As a result, these lies have the ability to erode the kind of shared reality that is necessary for democracy to function.”

“As a general matter, a shared sense of reality is a prerequisite for the healthy exchange of ideas necessary for any successful democracy,” Williams said. “But more specifically, our democracy cannot function if its people do not believe in the integrity or effectiveness of its elections. Baselessly attacking election workers only exacerbates the issue, because we need civil servants to administer those elections. If partisans are able to run off election workers, our elections grind to a halt.”

Williams also noted that the statements challenged in this case are “clearly” not protected by the First Amendment: “First Amendment protections are crucially important to democracy. However, the law of defamation properly reflects those protections and the statements we’ve challenged in this case are clearly not protected,” she said. “You cannot knowingly and intentionally spread lies about people, particularly when those lies were thoroughly and effectively debunked within 24 hours, as they were in this case.”

Similarly, former Sen. John Danforth, partner at Dowd Bennett, says he has been concerned about the attack on the integrity of the election in general.

“When an assertion is made that an election was stolen, the further danger is that this will become kind of a template for how future elections are conducted,” he said. “I think this is more than just a one off problem, but I think this is a general problem that was certainly given a huge push forward by President Trump and by Trump followers.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.