Several branches of the U.S. military are projected to fall well short of their recruitment goals for the fiscal year, despite numerous initiatives undertaken by all the branches designed to attract as many quality recruits as possible—a problem military brass says doesn’t have an easy fix.

The Army has been the hardest hit by recruiting struggles: It missed its goal by 25 percent (about 15,000 soldiers) in fiscal year 2022 and is projected to be about 10,000 soldiers short of its 65,000 goal this fiscal year. The Air Force, meanwhile, met its active-duty target in 2022 but expects to be 10,000 airmen short of its goal this year of almost 27,000, while the Navy expects to miss its target of almost 38,000 active-duty sailors by 6,000.

Many of the causes for the shortfalls are outside the military’s control, John Noonan, a former national security adviser to Sen. Tom Cotton, tells The Dispatch. Only 23 percent of Americans between the ages of 17 and 24 meet the physical and mental requirements for military service, with Army aptitude test scores falling by 10 percent during the COVID pandemic, according to the Army Times. Up to 70 percent of potential Army recruits are now disqualified in the first 48 hours due to obesity, low test scores, or drug use.

Similar problems plague other branches, and defense officials have responded by relaxing some standards: In January, the Navy raised its maximum age for new recruits from 39 to 41 and has experimented with lowering entrance exam requirements.

But data reveal other problems: Americans are not only less able to serve but also increasingly unwilling. Benefits that had once helped the military stand out against private sector employers, such as healthcare and tuition assistance, have become commonplace. In a tight post-pandemic labor market with less incentive for military service, the Army is engaged in an “intense competition for talent,” Lt. Gen. Douglas Stitt, deputy chief of staff for personnel of the Army, said at a House Armed Services subcommittee hearing in March.

The military has also faced sharply declining public confidence, which has dropped by 18 percentage points since 2009, according to Statista. Media portrayals of the military have contributed to negative perceptions of the Army in young adults, Army Vice Chief of Staff Randy George told lawmakers in April: Only 21 percent of young Americans surveyed believe that Army culture is consistent with their values and beliefs. Other concerns include fear of injury or death, post-traumatic stress disorder, and separation from friends and family, according to a 2022 Department of Defense survey.

In recent years, the military has also contended with accusations of “wokeness” from many conservatives—mostly thanks to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, plans to reduce its environmental impact, and progressive training videos and advertisements. The extent to which these factors actually influence recruitment is unclear: In 2022, only 5 percent of respondents to Army surveys listed “wokeness” as a reason for not enlisting, according to the Associated Press.

Meanwhile, voices on the left have accused the military of looking past right-wing extremism in its ranks, prompting Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in 2021 to order the establishment of a “Countering Extremist Activity Working Group.” Republican lawmakers such as Mississippi Sen. Roger Wicker have pushed back against that working group as well as Department of Defense DEI initiatives, arguing that while the recruiting crisis is all too real, military extremism is a “problem that doesn’t exist.” Such initiatives “dissuade young people from enlisting,” he said. “They suggest to the American people that the military has a problem with diversity and extremism.”

“You want everyone to feel like they are unifying behind a core American identity and a healthy patriotism,” Noonan tells The Dispatch. “That’s what motivates people to serve. And when you start distancing yourself from that message, you do start to isolate people because politics are inherently divisive.”

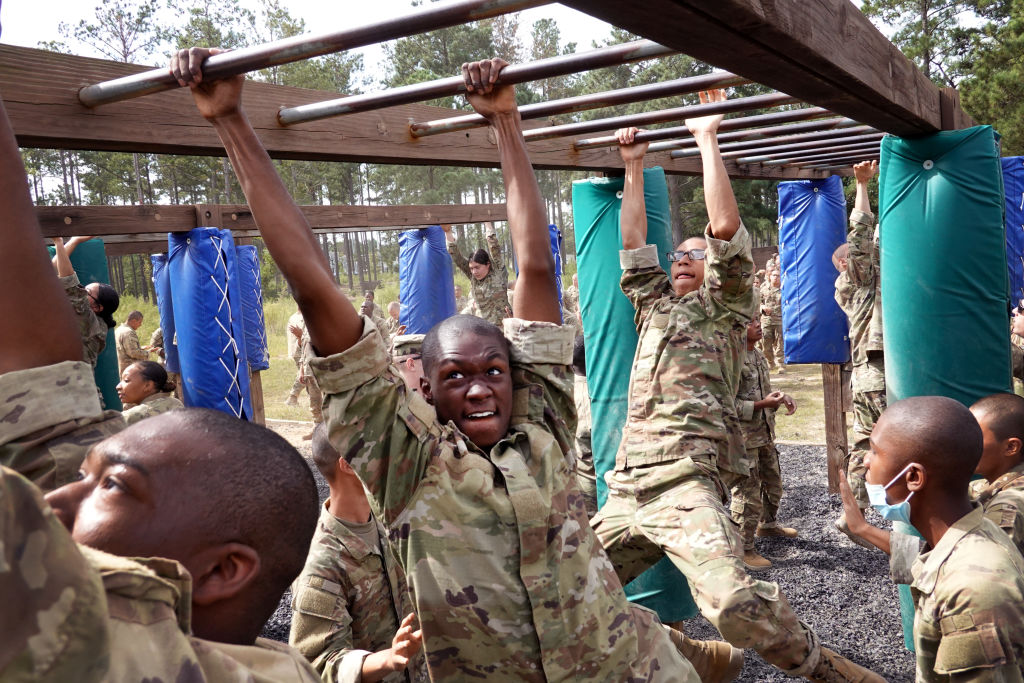

Whatever its mix of causes is, fixing the recruiting problem will require more than one solution. The Army, for instance, has instituted a Future Soldier Preparatory Course to help more youth meet the academic and physical standards for service. It’s also attempting to provide recruiters with better training and financial incentives and to launch marketing campaigns designed to improve young Americans’ perceptions of a military career.

The Government Accountability Office has recommended that the Department of Defense collect more data to know what’s working and what isn’t. “Today’s recruiting landscape did not emerge overnight,” Under Secretary of the Army Gabe Camarillo told Congress in March. “And it will take more than a year to solve.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.