KEREM SHALOM, Israel—Just miles from the point where Israel meets Gaza and Egypt, the Arab descendants of nomadic tribes are defending their country. At the Kerem Shalom military base—the headquarters of the Israeli army’s desert trackers unit, also known as the “Bedouin Battalion”—these soldiers, most of them Muslims, feel a strong sense of national pride and purpose in the wake of Hamas’ October 7 attack.

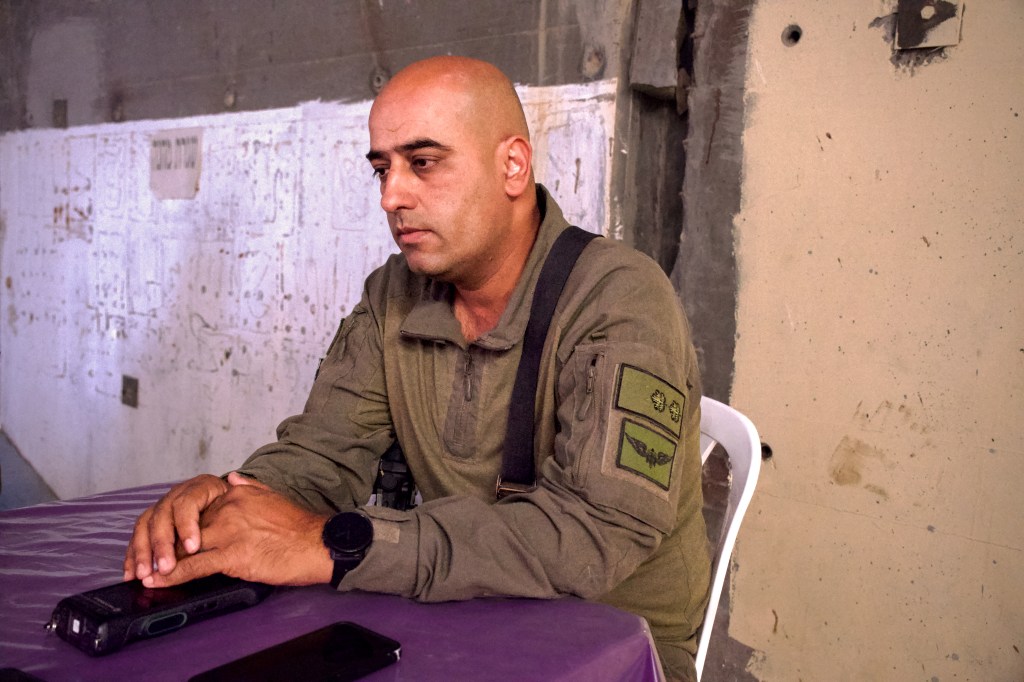

“I saw a woman shot in the head on October 7. Normally it’s army against army, but here’s a terrorist organization killing an innocent civilian,” said Lt. Col. Nader Idat, the battalion’s Bedouin commander. “I’m a Muslim myself and there’s no religion, including Islam, that says that it’s OK to kill. That’s what differentiates Hamas. Their purpose is to kill.”

And on that day, Hamas’ killing squads didn’t distinguish between combatants and civilians, Israelis and foreigners, Jews and non-Jews. The invaders murdered dozens of Bedouins—fellow Muslims and Arabs—and are believed to have abducted six others into the Gaza Strip, where three remain. Ever since, there has been a surge in voluntary army enlistment from within Israel’s Bedouin community, some 400,000 people—roughly 4 percent of the country’s total population—whose ancestors traversed the desert for trade and livestock rearing.

“The Bedouin community was traditionally a tribal community that engaged in trade by finding trade routes through the desert,” Iftah Burman, an Israeli geopolitical analyst and founder of the Middle East Learning Academy, told The Dispatch. “Over time, they passed down these techniques from father to son—how to travel in the desert, how to track the animals, how to make use out of vegetation. Those trades made them excellent trackers.” Since the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, he added, Bedouins have worked with Israeli forces to “patrol the borders, identify smugglers, and identify terrorists coming in through the borders.”

Many Bedouin soldiers have also fought and at least six have died alongside Jewish soldiers in this war. On October 7, as terrorists attacked the kibbutzim and military bases of the Western Negev, Bedouin troops were among the first on the scene. In one instance, a soldier took off part of his Israeli military uniform and spoke in Arabic to lure the attackers out of hiding before others shot them at close range. They’ve also deployed to the Gaza Strip, where they help locate terrorists, weapons, and tunnels.

At Kerem Shalom—the frequent site of Hamas rocket attacks—the Bedouin Battalion is one of Israel’s first lines of defense. On the day of my visit, an interview was abruptly moved to a shelter amid concerns of oncoming fire. “On October 7, [the soldiers] came here to take their weapons and started fighting right away with no question,” Idat said. “They’ve been here since.”

Bedouins currently enlist in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) on a voluntary basis, unlike Jewish men and women and Druze men—a non-Muslim, Arabic-speaking minority—for whom military service is compulsory. Prior to Hamas’ attack, voluntary military service among Bedouins was fairly uncommon, even stigmatized, in the often insular communities across Israel.

Now, Bedouin soldiers say they proudly wear their uniforms home. For many, joining the IDF also offers a pathway to integration into broader Israeli society. Bedouin troops can either pursue a military career after their nearly three-year enlistment period or enter the civilian workforce; both endeavors are aided by the Hebrew lessons taught on the military bases.

As one of the most poverty-stricken communities in the country, Israeli Bedouins are increasingly looking to military service to carve out a better life for themselves. But others have turned to crime, particularly the cross-border smuggling of drugs, weapons, and people from the West Bank and Sinai Peninsula. There have also been sporadic instances of Bedouin terrorist attacks, though Hamas’ efforts to recruit Bedouins to its cause have largely failed.

But ongoing land disputes between the Negev Bedouins and the Israeli government risks opening the door to extremism. The Bedouins have many recognized townships, but their claims over larger swaths of land and efforts to build unrecognized villages have put them at odds with Jerusalem, which sometimes orders the demolition of illegal construction. Establishing new neighborhoods requires the approval of Israel’s interior ministry, which has often rejected Bedouins’ right to build on state-owned land.

These communities also lack basic services like water and electricity, and the warning sirens and shelters that offer protection from weapons attacks in other Israeli municipalities. Iran’s attack on Israel in April underscored this unmet need, when shrapnel from an intercepted missile seriously injured a 7-year-old Bedouin girl at her home in the unrecognized Negev village of al-Fur’ah.

Despite what some have described as state neglect, many Bedouins identify proudly with their Israeli identity. That allegiance has only grown in the face of new threats to the country.

“We’re here in Israel, and we know exactly who Hamas is and what we’re up against,” Idat said from Kerem Shalom. Asked whether Bedouins are conflicted about which side to support in the ongoing war, the commander pulled his national identity card from his wallet and held it up: “I’m Israeli. I was born here and I’m going to fight for my country.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.