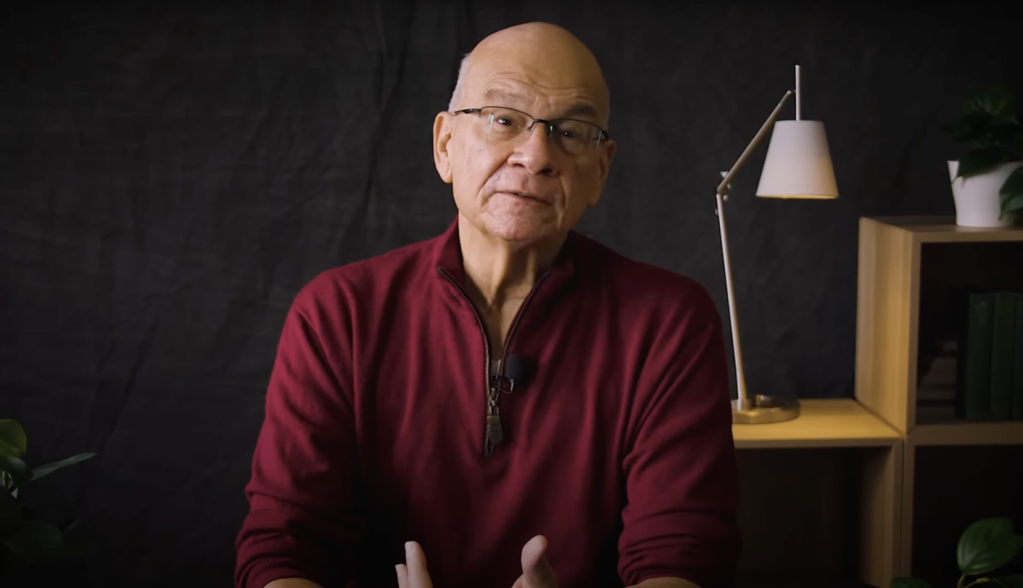

Even just hours before dying Friday of pancreatic cancer at age 72, Tim Keller’s final public words indicate he left the world the same way he lived in it—telling others about his faith. “I’m ready to see Jesus,” he said Thursday night, according to his son Michael. “I can’t wait to see Jesus. Take me home.”

It’s hard to quantify the impact of Keller, an author, New York City pastor, scholar, and intellectual leader. In many ways, he became America’s pastor.

Raised in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Keller became a Christian while a student at Bucknell University before attending Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and receiving a Doctor of Ministry degree from Westminster Seminary.

He began ministry humbly, as the pastor of West* Hopewell Presbyterian Church in Hopewell, Virginia. In the late 1980s his denomination—the Presbyterian Church in America—assigned him the task of finding someone to establish a new church in New York City. When no one else raised his hand, he did. As biographer Collin Hansen shares in his book, Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation, Keller thrust himself into the task of connecting the truths of the gospel with a city with a minuscule Evangelical presence, and thousands of New Yorkers converted to Christianity through the ministry of Redeemer Presbyterian Church.

Keller built Redeemer in the late 1990s in a way that was counterintuitive to the church growth movement of the time. While others built congregations by de-emphasizing the traditional symbols of Christianity and creating more seeker-sensitive entertainment environments, Keller insisted on preaching substantive messages from books of the Bible in a method commonly referred to as “expository preaching.” He was unafraid to address contemporary topics like sexual ethics in a city where the Christian vision of marriage and family was countercultural.

Idolatry was a frequent topic in Keller’s books and sermons, as he would often highlight the fallen human heart’s ability to become, in John Calvin’s words, “an idol-making factory.” Those idols could be money or sex, fame or security. They could be good things we exalt to ultimate things, robbing us of intimacy and joy with God. Yet his overriding message was one of grace. “We are more sinful and flawed than we ever dared believe,” Keller was fond of saying, “yet more loved and accepted in Jesus than we ever dared hope.” The Bible, to Keller, was not merely a collection of stories, admonitions, and inspiration, but one cohesive narrative pointing both to humans’ sinful condition and Jesus Christ as the only solution.

I first heard Keller preach in 2011 at an event for the Gospel Coalition, an organization he co-founded to equip Christians for ministry. I’d heard of Keller but hadn’t listened to him before. I was struck by his clarity, his knowledge of the scriptures, and his pastoral and apologetic approach. His message on Exodus connected the events of the Old Testament book to Christ in a way I’d never heard done before. I soon read his first book, A Reason for God, a defense of Christianity directly addressing the deepest questions and doubts people have about Christianity. The book changed my life, helping me approach evangelism—a lifetime passion of Keller’s—without defensiveness.

I devoured his books on marriage, preaching, work, justice, and other topics and grew from his wisdom and application of the scriptures. I can’t say it better than my friend Trevin Wax, a scholar and cultural commentator:

Keller’s writing and ministry became something of an anchor for me. He exuded a sense of calm no matter what was taking place. He didn’t get caught up in all kinds of drama. He was the epitome of a “non-anxious presence,” and he had a deep-rooted security in his faith that allowed him to interact with people of various beliefs with respect and kindness. He also cared deeply about the future of the church and the spread of the gospel globally.

It wasn’t just me. Keller’s profound impact on a generation of leaders came from urging them to embrace their cities with the message that salvation comes through believing and trusting in Christ. He launched church-planting networks, wrote church-planting manuals, and helped Christians recover a rich doctrine of creation that all equip believers to live out their faith in a variety of callings. After 9/11 devastated his city, Redeemer became a hub, meeting the needs of thousands of New Yorkers reeling from the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history, and Keller delivered one of his most well-known sermons, “Truth, Tears, Anger, and Grace.” The behind-the-scenes story of Redeemer’s impact on post-9/11 New York is told in a narrative podcast produced by the Gospel Coalition for the 20th anniversary of that tragic day.

As both the church and his national profile grew exponentially, Keller modeled a vision of cultural engagement that didn’t flinch from difficult questions. In 2017 Princeton Seminary* awarded him a prestigious prize named for Dutch theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper. But the once proudly Christian institution rescinded the award after intrepid critics discovered, to their chagrin, that Keller, like Kuyper, took the Bible’s teachings on sexuality seriously. Yet the New York pastor was also known for his warmth and gentleness, even toward those with whom he disagreed. When Princeton withdrew his prize, Keller went and delivered lectures associated with the award anyway, a magnanimous gesture that demonstrated his generous spirit.

In the last few years, a few Christian critics targeted him for being “too winsome” and capitulating to cultural mores—a critique that sounds strange to those who actually read him. What made Keller unique is his unusual blend: the heart of an evangelist, the approach of an apologist, the commitment of a pastor, and the precision of a theologian. In an era marked by celebrity culture and numerous church scandals, Keller was known for personal integrity, a hero you could meet and not be disappointed in. He often spoke in interviews, books, and articles of the necessity of regular spiritual disciplines. When asked about the secret to good preaching, I once heard him respond simply, “Reading through the Bible, year after year, day after day.” He also urged Christians to regularly read the Puritans, the church fathers, and to pray through the psalms.

Keller was a brilliant scholar who never flaunted his intellect. He could be prophetic without being condescending, always loving and tender, especially when speaking hard words to fellow believers. “Even when Keller chastised evangelicals, he spoke and wrote as a pastor with love for his flock,” Hansen writes. “As easily as Keller quoted obscure academics or New York Times columnists, he aimed to build up the local church.” He wasn’t embarrassed to be associated with Jesus, nor was he embarrassed to be associated with Jesus’ followers.

As he endured the painful reality of his fatal pancreatic cancer, Keller modeled what he had so faithfully taught, exhibiting faith as death approached. “If there is a God great enough to merit your anger over the suffering you witness or endure, then there is a God great enough to have reasons for allowing it that you can’t detect,” he wrote in The Atlantic. “It is not logical to believe in an infinite God and still be convinced that you can tally the sums of good and evil as he does, or to grow angry that he doesn’t always see things your way.”

It is fitting that the last few books Keller released centered on suffering, forgiveness, and Jesus’ resurrection. Keller was a gift to the church who lived what he believed. As he wrote in The King’s Cross:

On the Day of the Lord—the day that God makes everything right, the day that everything sad comes untrue—on that day the same thing will happen to your own hurts and sadness. You will find that the worst things that have ever happened to you will in the end only enhance your eternal delight. On that day, all of it will be turned inside out and you will know joy beyond the walls of the world. The joy of your glory will be that much greater for every scar you bear. So live in the light of the resurrection and renewal of this world, and of yourself, in a glorious, never-ending, joyful dance of grace.

Corrections, 5/22/23: This article has been updated to reflect that Keller pastored West Hopewell Presbyterian Church and received the Kuyper award from Princeton Seminary.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.