Conspiracy theories thrive in environments rife with motivated reasoning and mass confusion. The chaos of the Iowa caucuses earlier this week provided both in spades.

In the hours after the first votes of the 2020 presidential election cycle were cast, the Iowa Democratic Party proved unable to report the results. Only 62 percent of the vote was released the following day, with the remaining precincts reporting their final tallies at a slow drip throughout the week. By the time 100 percent of the results were finally published on Thursday, the process had been marred by not only justifiable accusations of incompetence and serious allegations of errors and inconsistencies, but conspiracy theories that lacked supporting evidence.

Central to the dysfunction in the Hawkeye State was a mysterious app—fittingly called Shadow—backed by Acronym, a self-described “nonprofit organization committed to building power and digital infrastructure for the progressive movement.” Emily Stewart put together an excellent explainer on the pair’s relationship over at Recode.

In a press conference on Tuesday addressing what went wrong the night before, Iowa Democratic Party Chair Troy Price blamed the app for the delays. “This was a coding error in one of the pieces on the back-end,” he said.

“While the app was recording data accurately, it was reporting out only partial data,” an official statement from the state party read. “We have determined that this was due to a coding issue in the reporting system.”

Almost immediately, rumors began to fly about ties between the campaign of South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg and those behind the app. Supporters of other candidates began to float theories connecting him to Shadow and suggesting he benefited from the technological breakdown.

Buttigieg—a polarizing candidate among the Democratic party’s younger, more liberal base—outperformed expectations in Iowa. The RealClearPolitics polling average in the state showed him in third with 16.8 percent of the vote going into the caucuses; he ended up edging ahead of Bernie Sanders by winning 26.2 percent of the pledged delegates.

In the early morning hours of February 4, as the chaos of the counting was unfolding, Rep. Ilhan Omar, who has endorsed Sanders, drew attention to the rumors.

A short time later, a tweet from @GotBerniesBack pointed to alleged ties between the Buttigieg campaign and individuals connected to the app, concluding, “this all reeks.” It has since been retweeted more than 1,200 times.

The next morning, Shaun King, a prominent Sanders surrogate, claimed “Pete’s team funded the company that built the failed election app in Iowa.”

It wasn’t just Bernie supporters spreading the claims. Kayleigh McEnany is the press secretary for Trump’s re-election campaign:

And Donald Trump Jr. weighed in:

Here are the facts surrounding Shadow, Acronym, and Mayor Pete.

The Buttigieg campaign paid Shadow $42,500, but they weren’t the only campaign to do so.

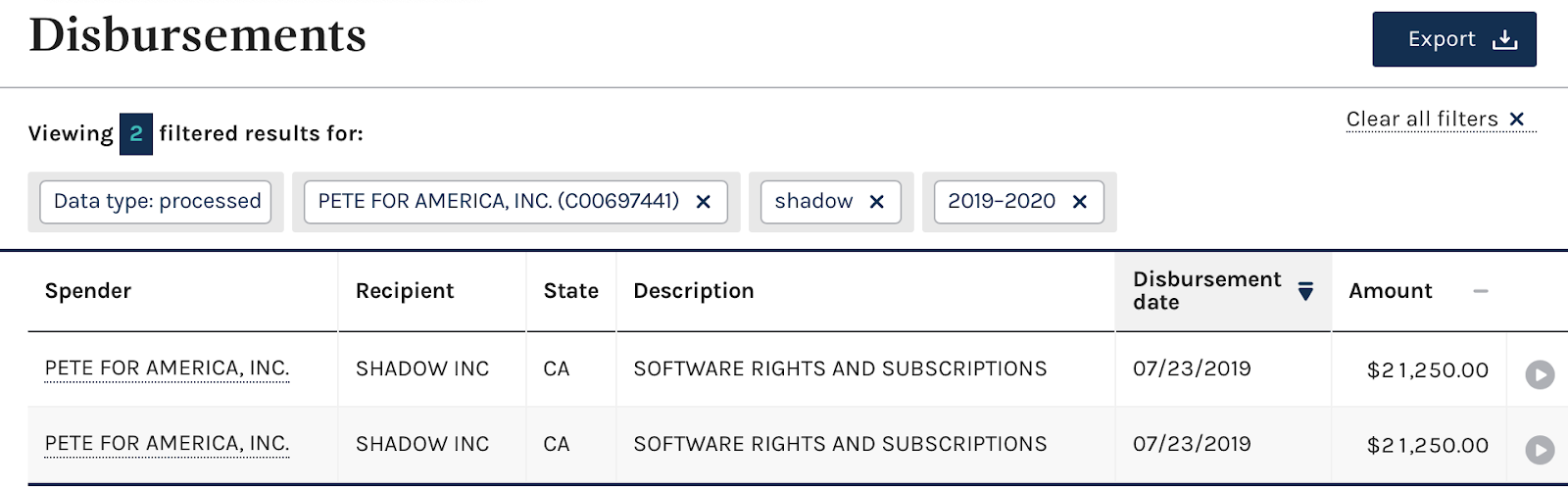

Pete For America made two separate payments of $21,250 to Shadow in July of 2019, according to filings with the Federal Election Commission.

A campaign spokesman acknowledged to The Dispatch that the Buttigieg campaign has contracted with Shadow. The relationship, however, was for “[text] messaging services to help us contact voters,” he said. “It’s totally unrelated to any apps they built for the party.”

But the Buttigieg team wasn’t alone. Kristen Gillibrand’s presidential campaign, which ended in August, spent $37,400 with the company. Joe Biden, who is very much still in the race and floundered in Iowa, gave Shadow $1,225. The Nevada State Democratic Party paid Shadow $58,000 in August—but promptly cut off its relationship with the company after the role it played in the Iowa debacle. “We will not be employing the same app or vendor used in the Iowa caucus,” a statement read.

The founder and CEO of Acronym, the organization behind Shadow, has demonstrated support for Pete Buttigieg’s campaign.

A quick scan through Tara McGowan’s Twitter feed illustrates the Acronym CEO’s backing of the former South Bend mayor.

“MAYOR PETE IS RUNNING 😍😍😍” she tweeted upon the candidate’s launch last January.

“Mayor Pete is an incredible candidate I am so, so excited to see get in this race,” she added.

In November, she dreamed of a potential Democratic ticket.

McGowan’s husband, Michael Halle, describes himself on Twitter as a “strategist for @Petebuttigieg,” and McGowan’s brother-in-law, Ben Halle, was Buttigieg’s Iowa communications director.

McGowan’s views on Bernie Sanders—Buttigieg’s main competition in Iowa—have been much less enthusiastic, though she did say last month she would “proudly vote for Bernie on Election Day if he is our candidate.”

McGowan did not address these previous expressions of support in a lengthy Medium post on Wednesday, but she did write that the group’s employees support a variety of candidates.

“We are proud to count among our ranks supporters for nearly every Democratic candidate, as well as former employees who are working for nearly all the leading Democratic campaigns. This diversity of viewpoint is something I’m incredibly proud of, it’s what makes us that much stronger and better prepared to take on the fight at hand, together. ACRONYM and PACRONYM will continue to stay neutral in the primary so that we can better focus on the common threat before us. But make no mistake, we will rally around and support whomever is the eventual Democratic nominee.”

The bottom line.

Political campaigns are notorious for their nepotism and self-dealing, and there is certainly some overlap here that raises questions about conflicts of interest. But there is no evidence that the caucuses were “rigged,” or that the problems with the Shadow app had anything to do with Buttigieg’s connections to those behind it.

Beyond that, such a conspiracy theory lacks common sense.

The Iowa caucuses take place out in the open. Citizens announce their votes by standing with others who support the same candidate—and they do so in front of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of other witnesses. Journalists from around the world descend on Iowa to cover the caucuses. International observers attend them. Some of the 1,765 caucus sites are covered on television. It’s simply not possible to secretly manipulate the results through an app when they’re among the most public electoral contests in the world.

There were undoubtedly problems with the app itself and errors with subsequent attempts to tally the results—that much is indisputable. But there is zero evidence that the problems with the app were orchestrated by the Buttigieg campaign or Buttigieg supporters—or anyone else, for that matter.

If you have a claim you would like to see us fact check, please send us an email at factcheck@thedispatch.com. If you would like to suggest a correction to this piece or any other Dispatch article, please email corrections@thedispatch.com

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.