Henry Kissinger did not have a great deal in common with the current commanders of the Israeli military except that he satisfied the American left’s definition of a war criminal: “any Jew gauche enough to take his own side in a fight.”

Kissinger was made to understand the necessity of taking his own side in a fight because, as a German Jew in the 1930s, there had been no one else to take his side. Kissinger was subjected to harassment and violence by the local Hitlerjugend and other Nazi thugs until his family finally was driven into exile, ultimately landing in New York City. Kissinger knew what Nazi Germany was all about, having grown up in the place, and one of his first acts of consequence as an American adult was to sign up to go back and fight the Nazis, which he did, serving with distinction at the Battle of the Bulge among other engagements. In a great (and once typical) example of American meritocracy, Kissinger was put in charge of the administration of a captured German city, a level of responsibility entirely incommensurate with his rank (private first class)—simply because he spoke German.

Kissinger next served as an intelligence operative, hunting down Gestapo officers, and was awarded a Bronze Star for his efforts. An American intelligence agent who had been, only a few years before, a German Jew—you can imagine what being captured would have meant for Kissinger, who nonetheless volunteered for hazardous assignments. Far from being a “war criminal,” Kissinger did good work helping to put some of the worst of that class into their graves.

Kissinger’s supposed crime was believing that, when at war, the U.S. military should drop its bombs where the enemy is rather than where the enemy would prefer those bombs be dropped. This was not a position he held without exception but as a general rule.

The Vietnam War was from the beginning a Democratic project, one of those many conflicts that a certain kind of prairie populist used to denounce as “Democrat wars.” But for political (and perhaps psychological) reasons that need not be explored extensively here, the American left felt obliged to make Vietnam into Richard Nixon’s war and, hence, Henry Kissinger’s war. (Never mind that the great contribution of Nixon and Kissinger to the Vietnam War was ending the thing.) The United States did not achieve its particular military goals in Vietnam, but, engaged on a dozen open and covert fronts, the United States did ultimately succeed in the larger project of which Vietnam was a part: winning the Cold War, defeating the worldwide communist enterprise.

For that success, Henry Kissinger never was forgiven, and never will be.

The legitimate criticisms of Kissinger the statesman include the fact that, as a matter of fact, many of his calculations were wrong, and that he very much represented a Cold War consensus in which American anti-communists were far too indulgent of brutality by anti-communist allies abroad. The crimes of figures such as Augusto Pinochet were obvious enough to Cold Warriors such as Margaret Thatcher, and they probably were obvious enough to almost everybody else, too, but many anti-communists pretended not to see them or pretended that they did not matter. That is our old intellectual enemy, “binary choice”—as though one could not prefer to see the communists defeated and acknowledge the misdeeds of Francisco Franco at the same time. I do not think that Henry Kissinger was an especially egregious offender on that front, but he did not, in that way at least, transcend his times. But, then, Kissinger wasn’t trying to imitate Mohandas K. Gandhi—he was trying to imitate Metternich.

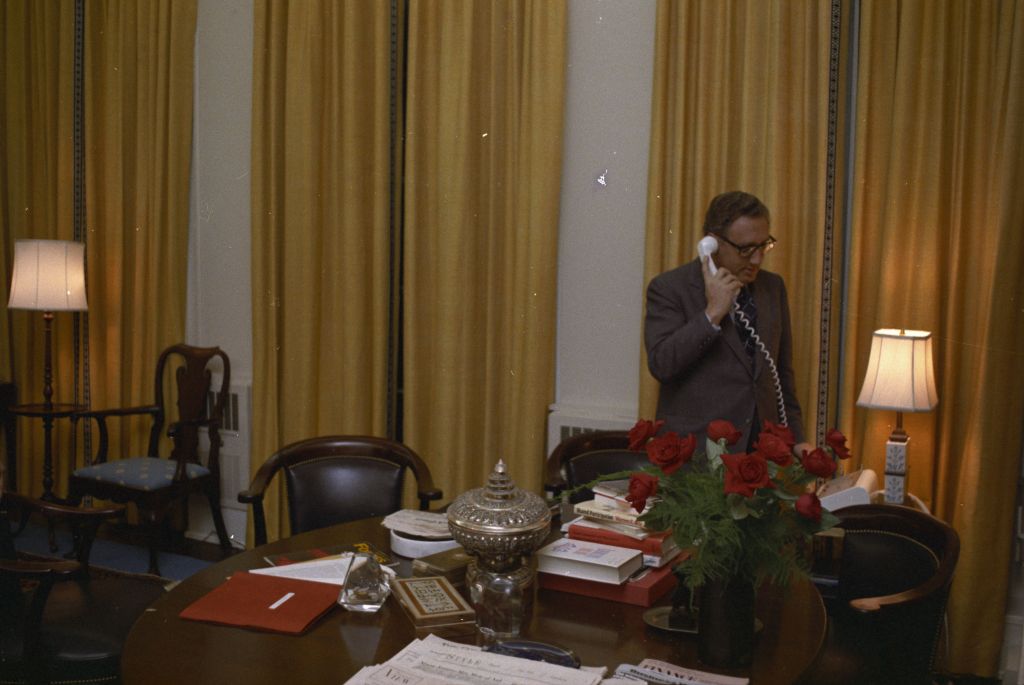

Kissinger the man had his shortcomings, to be sure. He was famously vain, for one thing, and at times put his own interests ahead of those he was meant to be serving. He also was very sociable and could be entirely charming. He never seems to have lost his capacity for being delighted in the company of beautiful women—the last time I saw him (conservative New York is a small place) he must have been at least 90, and there was nothing about him that seemed retired. I suppose that is part of how one lives to be 100 and remain productive until almost the end.

I do not think that Kissinger’s vanity necessarily extended to being called “Dr. Kissinger,” as he almost always was. (A long discussion, but: Nobody calls Phil Gramm “Dr. Gramm” in spite of his Ph.D. in economics, and nobody calls John Sununu “Dr. Sununu,” and he’s an MIT man with a doctorate in engineering.) Dr. Kissinger wasn’t like Dr. Jill Biden—his “Doctor” always seemed to savor of the Cold War dread of nefarious intellectuals, especially foreign-born ones: Dr. Strangelove, The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, etc. (Dr. Manhattan, like Dr. Kissinger, was German-American.) If Kissinger was not a humble man, it may be that he believed, like Winston Churchill, that it was his critics who had a great deal to be humble about.

Kissinger was one of the last adults in the room. He was a realist in the best sense of that word, not using realism as a place to hide from difficult moral and ideological questions but as a way of grounding policy and decision-making in the world as it actually exists. Though his ideas were somewhat modified over the years by events and experience, his thinking was very clear from the beginning: If you would like to understand the thinking of Henry Kissinger, you could do worse than to read his first book—A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-22—which is a published version of his doctoral dissertation. Among his interesting conclusions is that hyperpowers tend to make the world unstable by exposing every other power to “total insecurity,” making revolutionary regimes out of those that might have accepted a more balanced world order. For Kissinger, that was a descriptive rather than a prescriptive finding—that the aspirations of other nations and peoples have to be taken into account not because we believe them to be good or even legitimate, but because they matter empirically, as a matter of fact.

There will be no debate about whether Henry Kissinger lived a consequential life. There will be a great deal of debate about whether he lived a good one. There shouldn’t be: Kissinger was an extraordinarily effective advocate and diplomat, and he was on the right side of the most important conflicts of his time, while his opponents were, to great and greatly culpable degrees, on the wrong side. But as with Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger will never be forgiven for his role in winning the Cold War and securing American interests around the world.

That this should be regarded as a crime against humanity tells us more about Kissinger’s enemies than it does about the late secretary of state.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.