Pundits should take responsibility when they get something wrong. I will do so eventually for this prediction. But not yet.

I concede that there’s no evidence so far that Americans on the losing side of the last election “feel like the social contract itself is breaking.” Political analyst Mark Halperin expected, and I agreed, that seeing a failed coup–plotter return to power would “cause the biggest mental health crisis in the history of America,” but it hasn’t. Why it hasn’t is an interesting question—people have tuned out of politics momentarily, perhaps, or they’re clinging to hope during the president’s honeymoon that their worst fears won’t be realized. Or they’re too distracted by the pitiful state of the Democratic Party to focus on what he’s up to.

Or Halperin and I were just plain wrong, and millions of frogs whom we expected to be leaping out of the pot as it comes to a boil have already cooked through.

We’ll consider the matter at length at some point. But let’s hold off for now, in case Americans haven’t realized yet how hot the water’s already gotten and how much hotter it’s about to get. Denial takes time to penetrate. Let ‘em cook.

I feel weaselly promising to take accountability and then refusing to do so, though, so let me admit something else I got wrong. As dire as my predictions about a second Donald Trump presidency have been for the last two years, I did not expect it to get this bad this soon.

Since Friday:

1. The president unilaterally declared what the Wall Street Journal called “the dumbest trade war in history” on America’s two neighbors, which is based on blatantly false pretenses in Canada’s case, at least, and may or may not actually take effect after last-minute deals to postpone the tariffs were reached. He seems to think he might be able to pressure Canadians into, er, agreeing to be annexed by the United States. “We don’t need anything they have,” he insisted, boasting that without American trade Canada “ceases to exist as a viable country.” Gratuitously insulting a loyal ally to no obvious end: That’s diplomacy, Trump-style.

2. Dozens of federal prosecutors who worked on cases related to January 6 were fired by a 2020 election conspiracy theorist who’s currently serving as an interim U.S. attorney. Eight FBI executives were also purged and the acting bureau director was ordered to compile a de facto enemies list of agents who assisted in insurrection cases, presumably so that they can be purged too. The only thing they’ve done wrong, it appears, is to have held Trump’s foot soldiers accountable under the law. They went against The Family.

3. Elon Musk and a bunch of aides, some as young as 19 years old, have gained access to the U.S. Treasury’s checkbook and other elements of federal infrastructure and have begun to block payments to recipients they deem unworthy—which appears to be news to the president. The USAID agency in particular is being hollowed out (we’re “feeding [it] into the wood chipper,” Elon claimed) after Musk aides barged their way into the bureau’s headquarters on Saturday and gained access to classified systems over the objections of security. It’s unclear whether anyone involved had or has the requisite security clearances, let alone the legal authority, to do any of this.

4. Trump ordered the Army Corps of Engineers in California’s Tulare County to begin releasing vast amounts of water from two dams, apparently to show Americans how boldly he’s moving to cut through progressive red tape and address the local wildfires. Problem one: None of the water released is flowing to affected areas. Problem two: Locals were unprepared, risking flooding. Problem three: Farmers rely on that water during the dry summer months to irrigate their crops. Trump did get a nice Twitter post out of the episode, though.

5. Marco Rubio reportedly will name Darren Beattie as his acting deputy in charge of public diplomacy at the State Department. Beattie worked in Trump’s first administration before being fired—for attending a conference with white nationalists. He used the riot on January 6 as an occasion to warn various African Americans, including Sen. Tim Scott, to “take a knee” and “learn his place” in MAGA America. Beattie’s a fan of China’s Uyghur genocide, too, it turns out, and is hoping to see the United States barter away Taiwan’s independence to Beijing. If you want to understand the difference between Trump 1.0 and 2.0 at a glance, Beattie going from persona non grata to high-ranking American diplomat is hard to top.

“A little pain,” the president said on Sunday when asked by reporters what Americans could expect from his new tariffs on Canada and Mexico. Musk said something similar before the election, warning the country to expect “temporary hardship” following a Trump victory. All of two weeks into a second Trump administration, the magic beans have already begun to feel somewhat less magical.

The essential thing to remember as this nightmare plays out is that Congress could stop all of it at any time if it wanted to.

Caesarism is a choice.

Well, fine, not all of it. There’s nothing the legislature can do to send pardoned January 6 cop-bashers back to prison, for instance. They’re beyond the law’s reach now, free to return to their favorite pastimes.

And there’s nothing the House and Senate can do to prevent Trump from being the sort of imbecile who might flood a bunch of farmland just to show that he means business about making sure water is flowing in California.

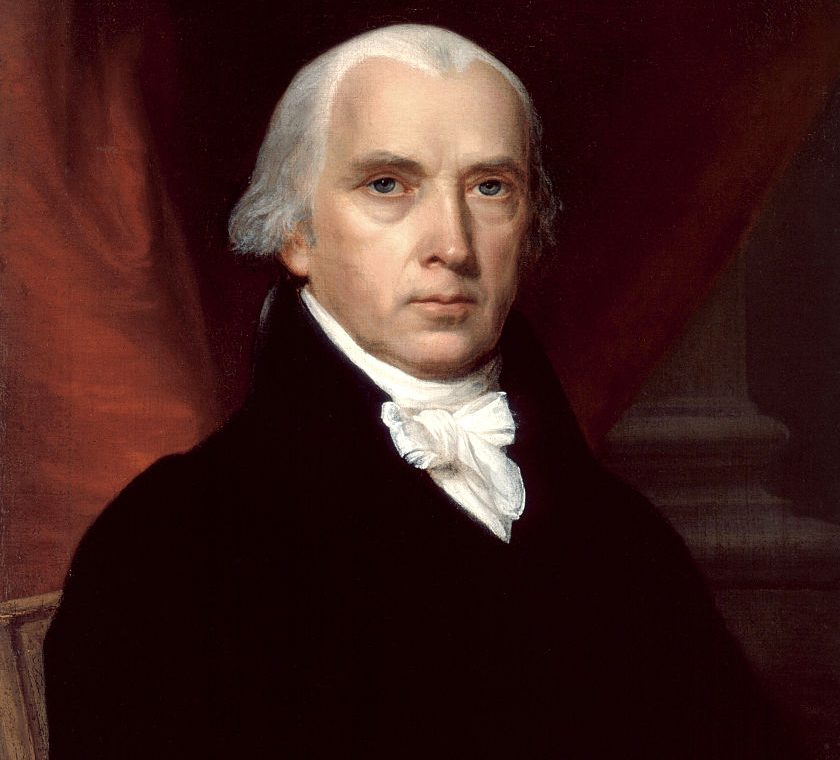

But Congress retains a lot of power on paper—parchment, specifically—to impede him and Musk as they run around setting the U.S. economy and the constitutional order on fire. A decade of self-abasing cowardice by congressional Republicans has convinced many Americans, I suspect, that there just isn’t anything to be done about what Trump is up to. Hogwash. James Madison gave Congress plenty of tools to maintain equipoise between the three federal branches and an institutional mandate to use them aggressively. It’s not that there’s nothing to be done, it’s that the legislature refuses to follow the Madisonian scheme by accepting its mandate.

Caesarism is a choice, and the people’s representatives are choosing it.

Trump’s trade war demonstrates that fact beautifully, as Republicans in Congress have every reason—political, legal, economic, diplomatic—to want to thwart him. Tariffs on Canada and Mexico would slow growth in the United States, raise the cost of living for Americans who are anxious about inflation, assuredly fail to stop fentanyl trafficking and illegal immigration, turbo-charge cronyism in policymaking, spark a nationalist backlash to Washington’s predation abroad and drive anxious allies into Beijing’s arms, and possibly lead corporate interests to move production from Mexico back to China to take advantage of lower tariffs.

Even loyal MAGA toadies like Sen. Rand Paul and Sen. Ron Johnson can’t feign enthusiasm for it.

The kicker is that arguably none of it is legal. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement that Trump signed in his first term is supposed to govern North American trade. It took less than two weeks for the new president to threaten to dump it in the shredder. Nor is there any emergency (certainly not on the northern border) that justifies him using the “emergency” powers over tariffs that rightly belong to Congress under Article I but which the legislature long ago foolishly granted to the executive by statute.

In a Madisonian system of separation of powers, the solution is obvious. The president has overstepped his constitutional authority, and he’s done so in a way that risks serious harm to the country, economically and diplomatically. Congress should defend the American people by asserting its own authority and punishing him for his trade war or one of his other dubious gambits this weekend.

For instance, the Senate could halt the confirmation process for Trump’s nominees or begin rejecting them outright to protest his power grabs. Last week Kash Patel promised there would be “no retributive actions taken” at the FBI. How can senators take that promise seriously and confirm him now knowing that retributive actions have already been taken? Why should it confirm any State Department deputies if Trump insists on insulting nonwhite Americans by offering a creature like Darren Beattie to represent them?

Congress could also exercise the power of the purse by refusing to approve Trump’s coming tax-cuts plan or shutting off the spigot of money for the president’s priorities until he gets Elon Musk to stop treating federal expenditures like a game of fiscal jenga. “‘World's richest man seizes control of U.S. Treasury and directs payments be made in accordance with his personal preferences’ is so far beyond a constitutional crisis that I don't even know what term to use,” one lawyer said of Musk’s chicanery this weekend. I didn’t like impoundment when Trump wanted to do it; I really don’t like it when an unelected plutocrat who hasn’t been confirmed by the Senate to anything asserts that power on Trump’s behalf.

But if that’s not enough to deter Trump, Congress could always go nuclear. Checks and balances aren’t symmetrical in the Madisonian scheme, remember: The legislature can pass any bill it likes and, subject to constitutional limitations, make that bill a law over the president’s objections by mustering two-thirds majorities in both chambers to override his veto. All it would take to undo Trump’s “emergency” tariff powers or to restore the USAID agency is 75 Republicans in the House and 20 in the Senate to vote with Democrats. The trade war would be over, never to recommence.

The Madisonian scheme understands that Caesarism is a choice and incentivizes legislators not to choose it. It recognizes ambitious politicians for the reptiles that they are and encourages them to hold each other in check by placing the three branches in conflict and forcing them to compete for power. If an imbalance should arise in favor of the president, as is currently the case with tariffs, the people’s representatives will jealously correct it by clawing some of that power back. In theory.

The flaw in the Madisonian scheme is that the people themselves might come to prefer Caesarism.

What did Americans vote for?

Madison’s vision is premised on the belief that Americans, not just their representatives, would resent assertions of monarchical power by the president. Which was a reasonable thing to believe in a country that had just overthrown the world’s most powerful sovereign and established a democratic republic.

It’s not a reasonable thing to believe anymore. Modern Americans view competitions for political power exclusively through a partisan lens. The only relevant conflict is Republicans versus Democrats; insofar as the Madisonian conflict between the three branches complicates that overarching conflict, it’s expected to yield to partisan interests.

That’s not to say that most Republicans want a Caesar. (Although plenty do. Don’t kid yourself.) What they want is for the Republican agenda, as articulated by the president, to prevail. If that means upending the Madisonian scheme by having congressional Republicans yield their power to Caesar, they’ll take that 10 times out of 10 over Republicans in the House and Senate siding with Democrats to vindicate Madison’s vision by blocking Trump’s autocratic pretensions.

This is the “civic disaster” in America that I mention in every other column but rarely define. A meaningful share of the public is now indifferent at best to the virtues of dividing power among the branches and hostile at worst if doing so is likely to mean that their party will achieve fewer of its goals. The personality cult around Trump and chronic frustration with Congress’ ability to solve major problems like immigration has intensified that Caesarist impulse too, to the point that most Republican voters have effectively outsourced their views on policy entirely to Trump. Tool around Twitter today, for instance, and you’ll find MAGA diehards alternatively arguing that tariffs are good for America and that exemptions for certain key sectors, like energy, are also good and that Trump halting tariffs entirely for a month are, indeed, likewise good.

A population that no longer values separation of powers and can no longer form judgments about policy independent of their partisan rooting interests even when a policy’s flaws are starkly obvious, as with tariffs, is a Madisonian nightmare. It’s a recipe for authoritarianism, standing the constitutional incentives for checks and balances on their head: Thanks to party primaries, instead of jealously guarding their own branch’s power, House and Senate GOPers now have a strong electoral reason to jealously guard the executive’s.

That’s why I expect Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Tulsi Gabbard, and Kash Patel to be narrowly confirmed this week even though the Senate will be voting in an environment of presidential purges and power grabs. And that’s also why there’s no scenario in which Congress would ever dare try to reclaim its tariff authority from Trump, no matter how disastrous his trade wars get. Congressional Republicans joining forces with Democrats to take any form of power away from Caesar would be considered a betrayal by many GOP voters more egregious than voting to impeach him after January 6 was. To hardcore Trumpers, the Madisonian scheme itself is, by nature, an affront to the system of government they truly hold dear.

And so we arrive at an interesting question: Did Americans vote for any of this in November?

They voted for cheaper eggs and a tighter border, no doubt. But did they vote for Trump to plunge Canada into recession for no discernible reason or for Elon Musk to rummage through federal workers’ personal information or for white nationalists to take charge of “public diplomacy” at State? Some soft Trump voters will spend the next four years (or longer!) bleating that they never voted for Caesarism. Did they?

Of course they did.

They didn’t vote for any of this specifically, perhaps, but never in American history has there been a clearer case of caveat emptor than Donald J. Trump running for reelection after January 6. The Atlantic’s Mark Leibovich gave the right answer when asked about the president’s loathsome scapegoating of diversity hiring after last week’s plane crash over Washington: “This, in some ways, is democracy at work because everyone knows what this guy was and this is perfectly predictable. People voted for it.”

Politico made the same point after Trump’s sudden—and then suddenly rescinded—spending freeze: “Throughout the election campaign, he told America repeatedly that he would reshape the federal government, root out (and even prosecute) his enemies, pardon supporters who were convicted of violent crimes, slash government spending programs en masse and ax huge numbers of federal jobs. And then he won 77 million votes to do exactly that. Those accusing Trump of being anti-democratic might note that this is largely democracy in action.”

Democracy in action. Everyone knows what this guy was. What else is there to say?

Americans knew they were voting for a predator. They didn’t know what forms his predation would take, precisely, but they surely knew their new leadership would be mean-spirited, volatile, opportunistically autocratic, and given to luxuriate in its own ruthlessness. Implicit in the Madisonian scheme is the assumption that Americans would never knowingly trust the Constitution to a full-spectrum miscreant like Trump who would aggressively test separation of powers. We’re about to find out if there’s anything left to Madison’s contraption once that assumption proves false.

We chose to become an unapologetically predatory nation on November 5, believing that we might suffer “a little pain” in the process. Instead we’re going to suffer a lot, and we’ll deserve it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.