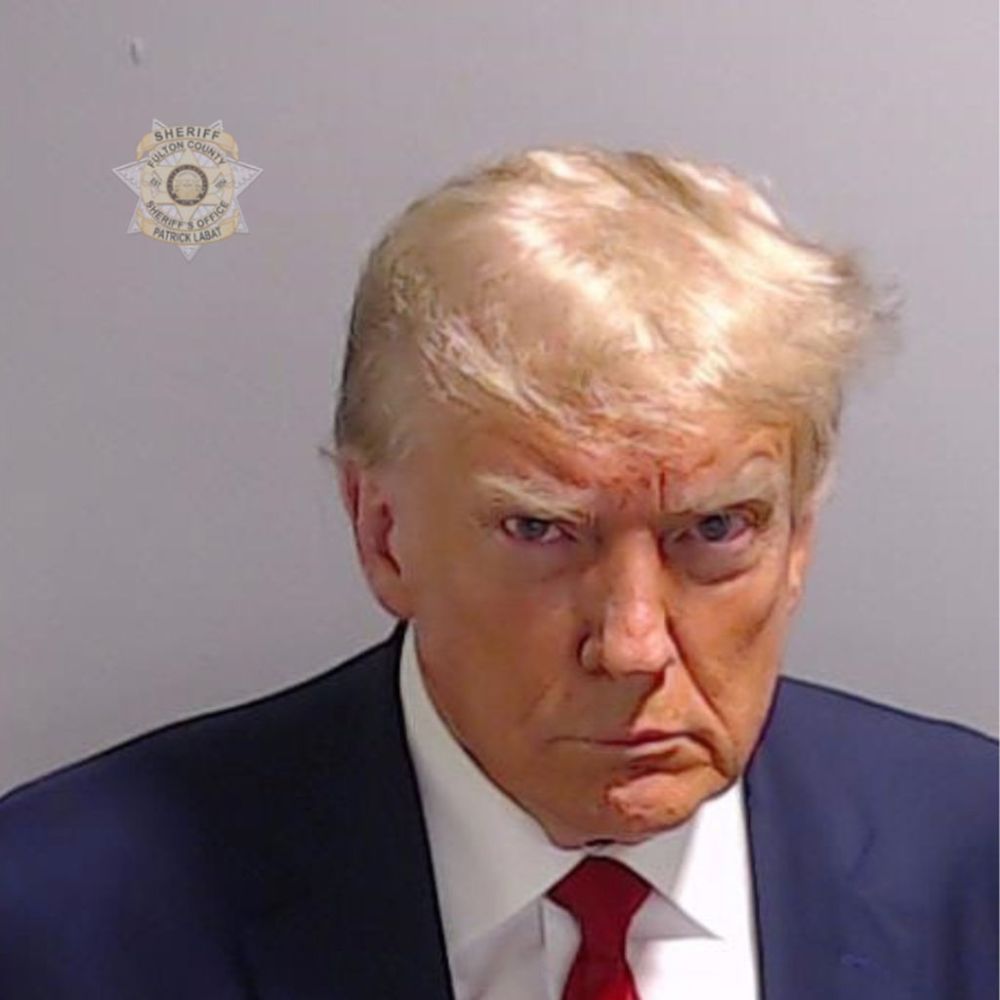

When Fulton County inmate P01135809’s mugshot was first released last Thursday, a number of adjectives likely jumped into your mind. Dour. Husky. Orange. Unless, of course, you host a show on Fox News. Then it made you think of one word, and one word only:

That wasn’t the only time Fox News’ new 8 p.m. guy reflected publicly on how, ahem, “hard” Donald Trump looks in his new mugshot. He did it again after Joe Biden mocked Trump by calling him a “handsome guy, wonderful guy” in response to a question about the photo. “That’s the first time Biden’s told the truth,” Jesse Watters told his audience. “It’s a handsome mugshot. My wife says he looks fierce. He looks hard.”

It’s interesting that Watters reacted to the photo with admiration more than anger. If ever there were a moment for the eternally aggrieved MAGA bloc to blow its top, one would think the indignity of its hero being forced to pose for a police mugshot would have been it.

Not so. There wasn’t much anger about it on social media this weekend. Again, rather the opposite.

Some even spun the photo as a political asset, offering certainly-not-racist speculation that voters in the “urban black community” will find an accused criminal to be relatable, if not admirable.

The irony, of course, is that it’s rural white communities (“real America!”) who’ll find the mugshot appealing more so than urban black ones. Which is bad—but also really odd given that those rural white communities are part of a political movement that purports to represent law and order, no?

Glorifying a mugshot is one of the most arresting countercultural signals a person can send. To celebrate the image of an accused criminal is to challenge the legitimacy of the system that’s accused him. Examples where that’s warranted come to mind easily; imagine a T-shirt with a mugshot of Martin Luther King Jr., for instance. A T-shirt with a mugshot of Donald Trump is … less warranted, but no less countercultural for being so. The Fox News talking heads and social media fanboys who have embraced his status as a criminal defendant are indicting the culture that aims to hold him accountable as unjust.

… while also holding themselves out as defenders of that culture against the lawless leftist hordes.

Sometime soon we’ll see a news photo from a Trump rally of an attendee wearing a mugshot T-shirt while carrying a “thin blue line” flag, oblivious to the contradiction. What should we make of that?

Can a political movement be reactionary and countercultural?

I have a bad habit of using the term “populism” as a catch-all to describe the post-Trump right when its excesses are often more precisely captured by other terms. Last week, Tom Nichols wrote this of Vivekmentum at the first Republican primary debate: “The GOP has mutated from a political party into an angry, unfocused, sometimes violent countercultural movement, whose members signal tribal solidarity by hating whatever they think most of their fellow citizens support. Ukraine? To hell with them! Government agencies? Disband them! Donald Trump? Pardon him!”

The word “countercultural” in that passage landed awkwardly for me, which may be a function of my age. To a child of the late 20th century, “countercultural” will forever mean hippies and their heirs among the utopian left. Even absent the historical pedigree, “countercultural” fits uncomfortably with a party like the GOP that skews older and whiter and disdains liberals for their comparative irreligion and lack of patriotism. It’s darned strange to think of a movement that one might charitably call “traditionalist” and less charitably “reactionary” as countercultural.

Strange, yet true.

Of course it’s true, a social conservative might say, marveling at my confusion. America’s educated governing class supports abortion, gay rights, trans rights, and lax immigration policies. If you’re pro-life, favor traditional marriage, think there are two genders, and prefer tighter borders, you’re countercultural by definition.

Right, fine. But Nichols is getting at something deeper than policy preferences when he uses the term “countercultural.”

He’s talking about a spirit of contrarianism toward the establishment so entrenched and consuming that it ends up losing its moral bearings. Traditionally, countercultural movements come together to challenge particular ideas of the governing class and end up challenging basic moral principles indiscriminately just because the governing class holds them. Not everyone who opposed the war in Vietnam was “countercultural,” for instance, but if you opposed the war and then decamped to a commune, believing “free love” was the future—yeah, that’s pretttttty countercultural.

A movement isn’t “countercultural” in the way we’ve typically understood that word until it begins to reject moral norms that the wider culture has traditionally taken for granted. That’s confounding in the earlier example I gave insofar as it’s the educated governing class, with its progressivism on gay rights and abortion, that’s more quintessentially countercultural than the social conservatives who oppose them. But it’s also why social conservatives view those victories as such an affront, I think. It’s not just a matter of finding the policies immoral or ill-advised, it’s a matter of countercultural forces—hippies, basically!—having seized the reins of the culture. It feels wrong.

A movement circa 2016 that rejected the Republican establishment’s supposed tolerance for “endless wars,” indifference to the collapse of America’s manufacturing base, and appetite for cheap labor from across the border wasn’t “countercultural” in the sense that we tend to think of that word. But a movement that now celebrates its leaders as “gangsta” after they’ve been arrested for crimes relating to a coup attempt?

Yeah, that’s pretttttty countercultural.

This right here? Also pretty countercultural.

It’s not “countercultural” to worry that the U.S. is sending too much aid to Ukraine. It’s incorrect, but one can believe in good faith that we’re hurting military readiness and risking a conflict between Russia and NATO by shipping huge stores of weapons to Kyiv.

But treating the aggressor in a war of conquest as a victim of religious persecution while they go about committing new and ever more creative war crimes? Countercultural. In fact, there are few turns in American politics as classically countercultural as apologetics for Russia. I grew up listening to left-wing tankies defend a communist regime in Moscow as fighting the good fight for global equality. Now I get to listen to right-wing tankies like Tucker defend a fascist regime in Moscow as fighting the good fight for Christianity—falsely, of course, in case the war crimes didn’t already clue you into Russia’s sincerity.

One might think that a reactionary movement preaching traditional norms to the godless left would be less susceptible to countercultural moral confusion than progressives are. If your shtick is God, country, and law and order, that should make you somewhat more resistant to applauding a mugshot of your party’s leader as “hard” or crying crocodile tears about the enemies of Christendom uniting against mother Russia. To all appearances, it hasn’t.

If anything, right-wing countercultural moral confusion looks more sinister at this moment than its left-wing ancestors did because it’s reinforced by religion. I recommend this short but essential social media thread by an exasperated pastor who can’t get through to his congregation that they’re practicing idolatry by refusing to hold Trump accountable for anything. They think they’re being good Christians by doing so, he says. Quote: “Support for this bully is fully equated with doing the will of God.”

Forget admiring his mugshot. If you’re giving up on Christianity because Jesus sounds more like a lib than like Trump, that’s about as countercultural as it’s possible to be. How did we land here?

I’ve been kicking around theories about that for almost a year.

Last September, in my second week on the job, I wrote about the importance of spite as an influence in countercultural populism. That column was inspired by another Tucker Carlson soundbite, in this case his unlikely eulogy for the late leader of the Hells Angels. Outlaw bikers aren’t typically wistfully remembered by (formerly) bowtied right-wing pundits, but Carlson had his reasons, I thought.

Specifically, nudging his fans to identify with the Angels was his way of encouraging them to question their assumptions about right and wrong. If you’re hoping to make the American right safe for illiberalism, some basic beliefs about who the good guys and bad guys are will need to be torn up by the roots. It’s because counterculturalism leads to moral confusion that Tucker is keen to propagate it, I think.

And so I predicted in the same column that, while Ron DeSantis was looking good in the polls at the time, that could change if Trump ended up being indicted. A spiteful party, blinded morally by its countercultural impulses, wouldn’t be able to resist nominating him if the criminal justice establishment tried to stop them: “Trump facing criminal charges really might lock up the nomination for him (before he’s locked up himself).”

How does that prediction look today?

In April, a few days after Trump’s first indictment in Manhattan, I argued that the blow to his electability would hurt him in the primary—if Republicans were still a normal political party. But they aren’t.

I think Trump’s movement is revolutionary in nature and will accept electoral defeats as the price of consolidating its power over the Republican Party. His supporters don’t care about building majorities because they no longer believe they can durably build them. Demographics and irreligion have conspired against them to deliver Democrats a more or less permanent advantage. And so Republicans have turned to nationalism, a system in which legitimacy conveniently doesn’t derive from democracy. Under nationalism, the tribe that rightfully rules isn’t the one that gets the most votes, it’s the tribe that embodies the nation’s demographic and cultural heritage.

In hindsight, “countercultural” might have been a better word than “revolutionary.” Revolutions are political and aim to seize power whereas countercultural movements are comfortable remaining in the minority. Win or lose, they retain their identity as adversaries of the establishment. (Yes, even when they take power and become the establishment themselves. Donald Trump is a mega-rich celebrity former president and never once have his fans accused him of being “establishment.”) In fact, insofar as losing feeds the sense of grievance that led them to become a countercultural movement in the first place, it’s arguably preferable.

There’s another reason the right has taken a shine to countercultural politics: It’s freeing. It can be downright thrilling. And it’s easy as hell relative to building a consensus policy platform or, God forbid, governing.

It’s why younger people have traditionally been sucked into countercultures more easily than older ones. It’s not just that they’re less invested in the status quo because they’re younger (although it’s partly that). It’s that they don’t have much to contribute to solving complicated problems that they don’t yet understand, so they revert to simplistic explanations of those problems that rely heavily on accusations of moral corruption. All that’s needed to be part of the movement is to muster righteous indignation at that corruption; once you’ve got that down, the solutions are a detail.

That’s what made Vivek “This isn’t that complicated, guys” Ramaswamy the countercultural candidate at last week’s debate. It’s also what makes Trump a superb countercultural leader. He was long on moral outrage at the establishment’s many failures in 2016, but never asked his fans to countenance solutions any more complicated than “build the wall.” Meanwhile, he’s spent his whole life flouting traditional norms—stay true to your wife, pay your debts, tell the truth—yet has succeeded professionally about as much as a human being could possibly succeed. If the defining trait of counterculturalism is moral confusion, who better to lead a countercultural movement than a guy who’s done everything the “wrong” way according to conventional morality and been rewarded for it at every turn?

Imagine how liberating it would be to live like that, doing anything you want and paying no price (until you’re 77 years old). His fans imagine it all the time, I suspect. No wonder they think he looks “hard” in his mugshot instead of pathetic.

One more nice thing about being ensconced in a counterculture is that it protects you from having your beliefs challenged.

For instance, you and I both know that between the traditional advantage of incumbency, Trump’s abiding unpopularity, and the sheer political weight of four indictments, Joe Biden is the favorite to win next year despite his diminished state. Not a strong favorite, but certainly no worse than a coin flip. You and I know that. Members of the counterculture do not.

Looking at that, is it any wonder that most (not all, most) political countercultures fail to replace the dominant culture? They’re perpetually working off of bad information because the goal isn’t to prevail so much as it is to reinforce the correctness of their beliefs. A movement that was keen to win would look soberly at Biden’s chances and choose a nominee based on a realistic assessment of victory with Trump. A movement that simply wants to exult in its conviction that The People are with them against the establishment—and will draw that conclusion no matter what the election results actually look like—doesn’t need to bother with such things.

The danger of MAGA 3.0 in 2024 relative to MAGA 1.0 in 2016 is that its moral confusion has plainly grown over time. Despite the movement having become more dominant in Republican politics, it’s also become more countercultural in its thinking. I don’t know what it will look like if America hands power to a political bloc that’s trending toward greater radicalism rather than away. Let’s maybe not find out.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.