We’ve all grown to expect the unexpected in American politics since the vortex opened in 2015 and we crossed over into the Darkest Timeline. But there are moments that still bring one up short, demanding a moment of wonder and reflection.

Behold the state of the “law and order” party, embodied here in the person of its most-watched television host.

Carlson didn’t just attend. He addressed the crowd of bikers and reportedly became emotional. He paraphrased a letter Sonny Barger had sent to his wife and friends: “’Stand tall, stay loyal, remain free, and always value honor.’ … And I thought to myself, if there is a phrase that sums up more perfectly what I want to be, what I aspire to be, and the kind of man I respect, I can’t think of a phrase that sums it up more perfectly than that.”

The kind of man he respects did multiple stints in prison, once for plotting to bomb the headquarters of a rival biker gang, and was charged with numerous other crimes, including murder. Some members of the gang he led wear a patch that reads “1%er” as a sly reference to the observation that 99 percent of bikers are law-abiding. They’re outlaws and they’re not ashamed of it. To the contrary.

This is not the cohort with which one would expect a former host of CNN’s Crossfire—a man who spends much of his time on-air indicting Democrats for lawlessness and whose personal style is most closely associated with the bowtie—to be commiserating. One can imagine how he’d react to Rachel Maddow getting choked up at the funeral of a mafia don, say.

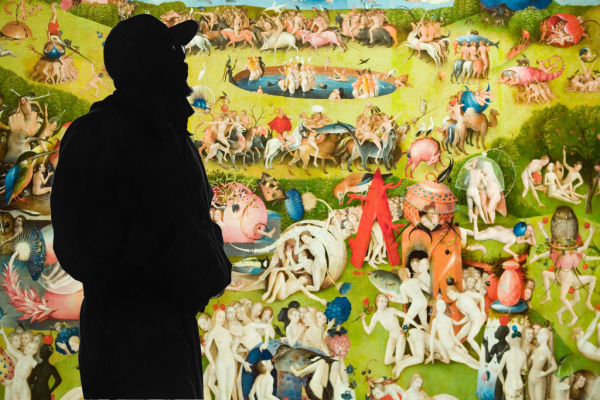

But I suspect there was a point to his attendance beyond the visceral thrill a member of the privileged class inevitably receives from fraternizing with roughnecks and radicals. (Tom Wolfe fans will have already thought of “Radical Chic,” with Tucker in the Leonard Bernstein role.) The point, I take it, was to associate himself with the spirit of rebellion against social norms that the Angels symbolize in the popular consciousness.

I’m reminded again of what J.D. Vance, a Carlson favorite, told an interviewer earlier this year, a line I quoted in another piece for The Dispatch last week. “We are in a late republican period,” he said. “If we’re going to push back against it, we’re going to have to get pretty wild, and pretty far out there, and go in directions that a lot of conservatives right now are uncomfortable with.”

To prevail in the culture war and take America back, Republicans are going to have to behave like, well, outlaws. Political 1%ers, if you will.

One wonders how long it’ll be before the Angels are hired to provide “security” at CPAC.

The cardinal virtue of modern conservative populism is spite. Whatever gambit a populist is pursuing, whatever agenda he or she might be advancing, the more it offends the enemy the more likely it is to be received by the right adoringly. Ron DeSantis’ Martha’s Vineyard stunt is an efficient example. It accomplished nothing meaningful yet observers on both sides agree that he helped his 2024 chances by pulling it off. He made the right people mad. That’s more important than thoughtful policy solutions.

Spite is there, too, in Carlson’s photo op with the Angels. Establishmentarians of either party wouldn’t be caught dead at a rally of outlaw bikers. “Suckers” like me were destined to scold him for his appearance once the photos appeared online, and he knew it. There’s an element of épater la bourgeoisie, unmistakably, to him showing up there. If you’re offended by him eulogizing the head of the Hells Angels, good. Then you’re exactly the type of weak-kneed chump he was hoping to offend by doing it, by definition.

Why spite has become so important to the right-wing populist ethic is hard to say, as it’s not symmetrical between the parties. The most prominent left-wing populist in Congress is probably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a politician who, despite her many faults, doesn’t want for policy ideas. Ask AOC what her top priority as a legislator is and she might say the Green New Deal or Medicare For All. The most prominent right-wing populist in Congress is likely Marjorie Taylor Greene. Ask Greene what she wants to do with her power as a legislator and she’s apt to say, “Impeach Joe Biden.”

“Impeach Joe Biden for what?” you might ask, as if that matters. When moderate-ish Republican Nancy Mace was asked on Sunday whether a new House Republican majority might impeach the president, she allowed that it’s within the realm of possibility—-without so much as gesturing toward what the grounds might be.

Spite doesn’t need a reason.

Left and right face the same structural pressures toward spitefulness. Most modern House members have more to fear from their primaries than from the general election thanks to remorseless gerrymandering and continued geographic self-sorting by voters. They’re compelled by social media to “perform” at all times, and they have unimaginably easy access to the wealth of grassroots activists thanks to Internet donation brokers like ActBlue and WinRed. All told, the incentives on both sides now point toward constant theatrical political combat, producing the dispiriting culture of lib- or con-owning “dunks” with which you’re familiar if you use Twitter. Online retail politics has become little more than a 24-hour stream of spite because political actors on both sides benefit from it being that way.

Where left and right differ is that the leadership of the populist left has a policy agenda whereas the leadership of the populist right does not, apart perhaps from “seal the border.” Trump didn’t run for president because there was a suite of legislation he was keen to pass, he ran because he didn’t want to end up as just another rich guy whom nobody remembers. It’s amazing yet true that the most significant policy achievement of his populist presidency was passing a traditional Republican tax cut written by Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell. He ran against foreign intervention, then bombed Syria within three months of being sworn in. He can be so incoherent and ill-informed on policy that, at one point in his term, he briefly came out for gun control.

As Trumpism has somewhat but not entirely dislodged the conservatism of Reagan, the right has been left with an identity crisis. Populists want one thing, traditional conservatives may want another, and the leader of the party often doesn’t know what he wants. The Republican National Committee dealt with that problem in 2020 by simply declining to adopt a new platform, punting on the subject by resolving to “support the president’s America-first agenda” without further specificity.

A party that can’t decide what it wants on policy can at least converge on the belief that the libs are bad and that whatever irritates them must have value. So spite has become the glue that holds together an uneasy coalition of classical liberals, nationalists, country clubbers, hawks, and social cons. And it’s no wonder that Trump has become its indispensable figure, as he relishes combat with his political enemies for its own sake and rose to fame with policies aimed at excluding undesirables (“build the wall,” the Muslim ban). Shortly before the 2020 election, Rich Lowry described him as “the only middle finger available” to the right in repudiating the cultural left. It’s hard to do better than that in capturing the spite that animates Trump-era populism.

Although I do often think of a quote from a woman interviewed by the New York Times halfway through Trump’s term in 2019. She had supported Trump over Hillary Clinton but was dismayed to see him presiding over a partial government shutdown. “I voted for him, and he’s the one who’s doing this,” she said. “I thought he was going to do good things. He’s not hurting the people he needs to be hurting.”

As a summary of the politics of spite, “hurt the people you need to be hurting” isn’t half-bad either.

Different political actors are drawn to spite for different reasons. For Trump, I think it’s temperamental. He’s a vindictive personality; of course he enjoys spiting his antagonists. For others, like DeSantis, spite is designed to demonstrate ruthlessness. It communicates that he’s a “fighter,” resolute in pursuing the right’s culture-war goals by making the Democrats howl about it. That makes him presidential material. For still others, like Republican strategists, spite performs the function of glue that I described above. At a moment when some members of the Republican coalition might be wavering over, say, abortion policy, a big show of spite in which migrants are airdropped into Martha’s Vineyard for the limousine liberals there to sort out might cheer them and bring them back on the team.

For someone like Carlson, I suspect there’s a strategy to spitefulness. When Tucker shows up to backslap the Hells Angels, he’s not just trying to get a rise out of Democrats and normie conservatives. I think it’s part of his effort to condition right-wingers to a new type of politics by encouraging them to question their traditional assumptions of right and wrong. Sure, the establishment says crime syndicates are bad even if they happen to ride Harleys and mumble platitudes about freedom. But since when do you let the establishment do your thinking for you?

I’ve always believed conditioning the right was the barely hidden goal of Carlson’s Russia apologetics. In March, the economist Noah Smith astutely diagnosed the reason the socialist left and the authoritarian right each seemed so invested in seeing Putin prevail in Ukraine:

Both the liberal center-Left and the conservative center-Right are basically committed to upholding the global liberal order. Putin, by invading and attempting to conquer a sovereign state, challenges that order. If Putin succeeds, even modestly, it represents a failure for the U.S. establishment figures who tried to stop him. And establishment failures equal insurgent opportunities. Both the rightists and the leftists here are fighting against the Fukuyaman end-of-history idea that gives their own movements little space to move up.

If Putin defeats the Ukrainians, the conservatives that are standing against Putin will look ineffectual and weak. The Trumpists will then be able to solidify their control over the GOP. And it also means a victory for raw power and will (perhaps implying that efforts like the January 6th putsch are the preferred method for attaining power). But if Putin loses, then Trump and his allies who for years praised and defended Putin’s regime will be discredited. Success has a thousand fathers; failure is an orphan. Even more damningly, if Putin loses, it’ll be a success for the globalist order — sanctions and aid to Ukraine will represent a triumph of international cooperation. Exactly the kind of world order the Trumpists want so badly to smash.

Carlson understands that convincing the right to ditch traditional conservatism for illiberalism requires uninstalling a lot of civic and cultural software. Republicans who grew up during the Cold War have fear and loathing of Russia in their political DNA. Republicans have traditionally trended toward interventionism, seeing strength in military power and weakness in Democrats’ hesitancy to use it. Republicans instinctively sympathize with Ukraine as an underdog and a fledgling democracy fighting to oust a colonial power.

Nationalists will never build the sort of post-liberal authoritarian system they want as long as those beliefs persist, so Carlson has made a mission of challenging them: Why are we rooting for Vladimir Putin to lose, exactly? What has he ever done to us? Why spend tens of billions of dollars to arm a country most of us can’t find on a map? Are we sure Russia is more corrupt than Ukraine? Why should we prefer a European-style democracy to an Orbanist strongman?

If Russia prevails in Ukraine over the West, it’ll create the sort of political space for insurgents that Smith describes—but only if the right is willing to claim that space. That’s what Carlson’s conditioning program is about, I think. He’s trying to cultivate in his audience an instinct to question—or spite—liberal pieties wherever they arise, from grand-scale geopolitics like “Russia is bad” to more pedestrian but no less correct beliefs like “Biker gangs are bad.” If nationalists intend to see their rebellion against liberalism succeed, they can’t let the enemy dictate to them what their morals should be. One small but vivid way to signal that is to show up as the guest speaker at Sonny Barger’s funeral.

If it bothers you, well, it figures that it would, lib.

Nothing better illustrates how important spite is to the Trump-era GOP than the conventional wisdom that quickly formed after the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago. Any other politician who had their home searched for stolen classified material by federal agents would, at a minimum, be damaged by the process. Hillary Clinton wasn’t damaged enough by her email scandal in 2016 to lose a primary to Bernie Sanders, but she was damaged enough to lose a general election to Donald Trump. No one on either side thought the FBI investigation of Clinton’s servers was an asset to her campaign instead of a liability.

But when Mar-a-Lago was searched, some Trump cronies sounded positively giddy at the development. “I think this basically makes it impossible for a DeSantis [run] now,” said one Trump adviser to Puck. Another happily proclaimed that “The DeSantasy is over!” Many political commentators agreed. The populist impulse to spite the Biden Justice Department by nominating Trump a third time would extinguish DeSantis’ chances, they believed. That the governor is plainly more electable than a twice-impeached disgraced former president facing multiple criminal investigations was neither here nor there.

I’m not convinced yet that DeSantis is licked. But if Trump is indicted, all bets are off. The essence of spite, after all, is being willing to damage yourself for the sake of antagonizing your enemy. And since a criminal indictment would bring maximum antagonism between the parties, one might safely assume it will also evoke maximum spite. Trump facing criminal charges really might lock up the nomination for him (before he’s locked up himself). How’s that for a “law and order” party for you?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.