Happy New Year. While most of us were holiday hibernating, venerable steelmaker and longstanding champion of American economic nationalism U.S. Steel gleefully agreed to be acquired by its onetime nemesis, Japanese multinational Nippon Steel. Since U.S. Steel had been on the auction block since the summer (when Ohio-based Cleveland Cliffs, backed by the United Steelworkers union, initiated an unsolicited buyout that U.S. Steel quickly rejected), the only surprising thing about the sale announcement was the name of the acquirer: Nippon Steel had never been mentioned as a possible suitor. Beyond that, the announcement gave us little to get worked up about. U.S. Steel would keep its name; Nippon Steel would honor existing USW and other contracts; and the merged company was eyeing domestic expansion (to meet an expected increase in steel demand), not painful contraction.

Within hours of the announcement, however, people did get worked up. In particular, the USW and a bipartisan cadre of protectionist politicians, wonks, and pundits denounced the deal as undermining national security and the U.S. industrial base, threatening American workers, and revealing fundamental flaws in corporate governance and U.S. regulation, which (supposedly) prioritizes shareholders and managers over the former priorities. A trio of Pennsylvania Democrats (Sens. Bob Casey and John Fetterman, along with Rep. Chris Deluzio) and a trio of “national conservative” Republicans (Sens. J.D. Vance, Marco Rubio, and Josh Hawley) each wrote to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, chairwoman of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), to block the transaction because of its “dire” implications for the U.S. industrial base and national security. The pols and pundits were followed by President Biden himself, who—via economic adviser Lael Brainard—didn’t go so far as to oppose the deal but instead pulled the classic Washington move of calling for an “investigation” by CFIUS … while explicitly praising the USW (whose support they think they need in 2024). The union, the Financial Times reported, “welcomed Brainard’s intervention.”

(Of course it did.)

As we’ll discuss today, this protectionist caterwauling is ridiculous. Though details will of course matter, the acquisition in general raises zero economic or security concerns, and it could very well benefit U.S. Steel’s domestic facilities and workers (and thus American steelmaking capacity). Just as importantly, the deal was the predictable result of the very protectionism and industrial policy that today’s critics say they champion. But this predictable nothingburger is still important for at least one big reason: It speaks volumes about today’s protectionists.

And none of it’s good.

The Bogus Case Against the Nippon Steel Deal

Let’s start with the economic insignificance of the deal in question—and U.S. Steel. As National Review’s Dominic Pino explains, the company was once vital to the U.S. industrial base and a major American employer, but it has shrunk dramatically since the 1970s and today employs just 20,000 people. That figure might sound like a lot, but it represents a mere 0.012 percent of the U.S. workforce and 0.15 percent of our manufacturing workforce. (The United States actually gained more manufacturing jobs in November 2023—28,000—than the total number of people employed by U.S. Steel!) In terms of market capitalization, meanwhile, U.S. Steel was the 572nd most valuable company in the United States when the Nippon Steel deal was announced, thus causing the company’s stock to surge. (Pre-deal, it was in the low 900s!) The company dropped out of the S&P 500 in 2014 and, in terms of crude steel output, now ranks just third in the United States—about 18 percent of total domestic output—and 27th in the world. This isn’t your grandfather’s U.S. Steel.

It isn’t his Nippon Steel, either, by the way. Although that company was once closely connected to the Japanese government (and Japanese industrial policy), those days are long over. Today, Nippon Steel is a private multinational corporation, with stock traded publicly on Japanese and U.S. over-the-counter markets, steelmaking facilities all over the world, and a large share (23 percent) of foreign ownership. And while protectionism and government intervention were once core features of the Japanese steel market, high tariffs and distortive foreign exchange controls were phased out in the 1960s and more liberalization has followed. Today, Japan’s steel market is fairly market-oriented—in many ways more market-oriented than the U.S. steel market.

For example, the World Trade Organization reports that Japan’s average tariff rates on steel and steel products are the same or a bit lower than those of the United States; Japan’s highest tariffs on these goods are nearly four times lower (3.3 percent vs. 12.5 percent); and Tokyo allows significantly more steel products to enter the Japanese market duty-free than does Washington into the United States. Japan also applies only 15 “trade remedy” restrictions (anti-dumping, countervailing duty, or safeguard) on steel imports, compared to the hundreds that are applied here. And, of course, the United States also applies those 25 percent “national security” tariffs and related quotas—policies that have no Japanese analog.

That isn’t to say Nippon Steel is some sort of free-market poster child—this is the global steel sector, after all, where government involvement has long been pervasive. But “when you push the sentimentalism aside,” Pino notes, all we really have here is “a relatively large publicly traded company in a global industry … purchasing a much smaller publicly traded company in a way that will have negligible effects on industry consolidation either globally or within the United States.” That’s hardly grounds for the ensuing political hysteria.

The “national security” arguments are similarly empty. Japan has been one of the United States’ closest allies for more than 60 years (dating back to the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty of 1960) and today hosts not only 55,000 U.S. military personnel and thousands of Department of Defense civilians and family members, but also the United States’ most advanced military assets, “including the U.S.S. Ronald Reagan carrier strike group and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.” As a result of the governments’ numerous defense-related procurement agreements, Japan acquires more than 90 percent of its defense imports from the United States, totaling tens of billions of dollars in government-to-government sales. Indeed, just days after the Nippon Steel deal was announced, the Japanese government literally changed its domestic law so it could sell American-designed Patriot missiles—manufactured by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Japan under a license from U.S.-based Raytheon and Lockheed Martin—to the U.S. government for potential use in Ukraine. (Very similar, by the way, to the type of defense-related manufacturing and procurement partnership I advocated in this 2021 paper, with Japan specifically mentioned.)

Japan’s close relationship to the United States—and its important role in countering China’s influence in the Asia-Pacific region—extends to private investors like Nippon Steel. As the Congressional Research Service recently documented, Japanese investors haven’t been a CFIUS concern since the 1980s (today it’s all about China). In fact, per the Hudson Institute’s William Chou, the hawkish bipartisan House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party just recommended that Congress put Japan on the CFIUS “whitelist” of close allies—a list that includes Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom and exempts their investors from CFIUS jurisdiction for many U.S. transactions. Knee-jerk opposition to the Nippon Steel deal, note Chou and others (including Col. Heino Klinck, who served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for East Asia under former President Trump), is not only groundless but also undermines important U.S. national security objectives.

Steel-specific security concerns are also silly. Even leaving aside the utter vacuity of the Trump administration’s “national security” findings regarding global steel imports and tariffs, recall that President Trump’s own secretary of defense, James Mattis, wrote during that investigation that “US military requirements for steel and aluminum each only represent about three percent of US production.” At the same time, Trump’s own secretary of commerce, Wilbur Ross—who oversaw the aforementioned “national security” investigation of steel imports—noted in supporting the Nippon Steel acquisition that idled steelmaking capacity in the United States today exceeds U.S. Steel’s total steel output. Double or even triple DOD steel consumption and shut down U.S. Steel entirely, and there’d still be plenty of domestic steelmaking capacity available.

Even this calculus, however, overstates the security risk here for three big reasons. First, as a previous U.S. government investigation of steel imports documented, even a large-scale military conflict wouldn’t strain U.S. steelmaking capacity because DOD needs are simply tiny relative to U.S. production (emphasis mine):

Even if entirely unforeseen events were to generate national defense-related demands for steel that were greater than DOD forecasts, such demands would still consume only a very small percentage of total U.S. steel output. To take just one example: DOD indicated that 60,000 net tons of finished steel was used in the multi-year construction of the U.S. Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, the USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76). Sixty thousand net tons constitutes less than one-tenth of 1 percent of total U.S. annual steel output. Accordingly, DOD could double the U.S. Navy’s entire fleet of aircraft carriers, and still not substantially vary the total percentage of U.S. domestic output attributed to national security uses.

Second, as that same investigation noted and as the aforementioned Patriot missile example recently demonstrated, the U.S. would still have access to imports from close allies like Canada that are both easily accessible and raise no security risks.

Third, and most important, Nippon Steel isn’t going to shutter U.S. Steel and will more likely strengthen it. The large premium was paid because, rightly or wrongly, Nippon Steel’s management sees the deal as an opportunity for growth and expansion in the notoriously closed U.S. market. And, as we discussed here back in 2021, foreign investment—including mergers and acquisitions like this—is usually good for both the U.S. economy and the U.S. companies getting acquired (and their American workers). Dartmouth’s Matthew Slaughter provided additional data last week:

Inward foreign direct investment by companies like Nippon Steel boosts America’s economic competitiveness. Although U.S. affiliates of foreign multinational enterprises comprise less than 1% of U.S. companies, in 2021 these affiliates in America accounted for 13% of business spending on research and development, 17.3% of investment in plant and equipment, and 23.6% of total goods exports.

All these activities contribute to successful businesses and high-productivity, high-paying jobs. In 2021 these affiliates employed more than 7.9 million U.S. workers, of which 35% were in manufacturing, far higher than manufacturing’s 9.7% share of all U.S. private-sector jobs today. Total annual compensation at these companies averaged $86,859 per worker—about 22% above the average for the rest of the private sector. Workers at globally engaged companies tend to earn more than comparable workers at purely domestic companies because global engagement fosters innovation and growth.

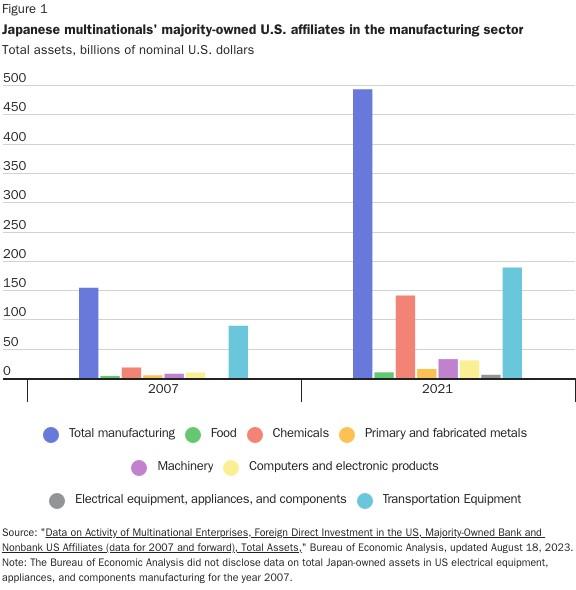

Japanese companies are a standout in this regard—including in the industrial Midwest. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Japan has long been the single biggest source country for foreign investment in the United States, with almost $712 billion invested here as of end-2022. This sum most famously includes the many Japanese automotive plants across the country, and those holdings are indeed huge (almost $190 billion as of 2021). But the BEA data also show that Japanese multinationals own increasingly large majority stakes in a wide variety of other U.S. manufacturing companies, including ones with possible “security” concerns like food ($10 billion), chemicals ($140 billion), and metals ($15.5 billion):

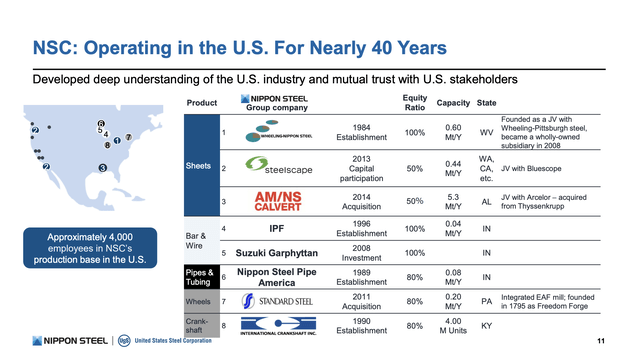

Those U.S. metals investments are particularly noteworthy here because some of them include … wait for it … Nippon Steel-affiliated facilities. As Slaughter notes, several thousand of the 963,000 Americans today employed by Japanese companies in the United States work at affiliates of Nippon Steel, “which itself has been operating in the U.S. since the early 1980s.” (According to its website, Nippon Steel already owns large stakes in eight different steel manufacturing facilities across the country.)

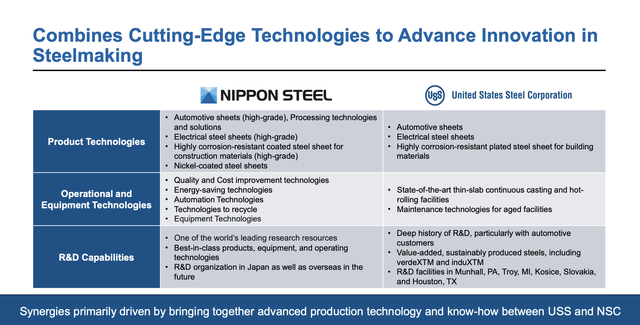

As I explained back in 2021, research shows that foreign acquisitions of existing U.S. companies can produce big benefits for the target firms and the communities in which they’re located. Improvements can occur through increased parent-company spending on R&D and capital equipment in the United States or through various internal changes (e.g., management or business practices or the implementation of proprietary technologies) at the new affiliates’ locations. Both companies believe Nippon Steel would do similar things for U.S. Steel, in part by creating a global steel behemoth that could act as a counterweight to China’s steel giants (the combined entity would be second in total output to China’s Baowu). Here’s how the company’s management explained the “synergies” in their shareholder presentation:

It isn’t, by the way, just globalists and corporate shills who know how a Japanese acquisition can benefit a U.S. steel facility. J.D. Vance himself wrote about this very thing in Hillbilly Elegy:

The Kawasaki merger [with Ohio-based Armco] represented an inconvenient truth: Manufacturing in America was a tough business in the post-globalization world. … If companies like Armco were going to survive, they would have to retool. Kawasaki gave Armco a chance, and Middletown’s flagship company probably would not have survived without it.

Gee, I wonder what changed?

It remains to be seen whether U.S. Steel actually will improve and thus justify the huge premium Nippon Steel just paid for it, but many industry experts believe the answer to both is in the affirmative:

“There will be a $1 billion capital project every year for the next 10 years if Nippon buys this,” said Tumazos, the son of an Edgar Thomson Works steelworker and a Carnegie Mellon University alumnus who has tracked trends in the metals industry for 44 years. He worked for various outfits before founding Very Independent Research in 2007. “These politicians and union guys are attacking this thing that’s going to save their bacon.”

…

Josh Spoores echoed that Nippon Steel’s purchase would come in tandem with renewed investment — though in more muted terms. “I do expect for them to come and invest in some production lines in the U.S.,” said Spoores, the Pittsburgh-based principal steel analyst for CRU, a business intelligence firm headquartered in London. “It’s probably an upgrade to get Japanese ownership.”

Other analysts, for what it’s worth, don’t think the premium is justified, while others still think it’ll get rejected by U.S. regulators because of election-year politics (bah). But nobody—nobody—who studies this stuff thinks that Nippon Steel is buying U.S. Steel to shut it down, or that the transaction otherwise raises broad and legitimate national security risks.

Protectionism Does What It Does

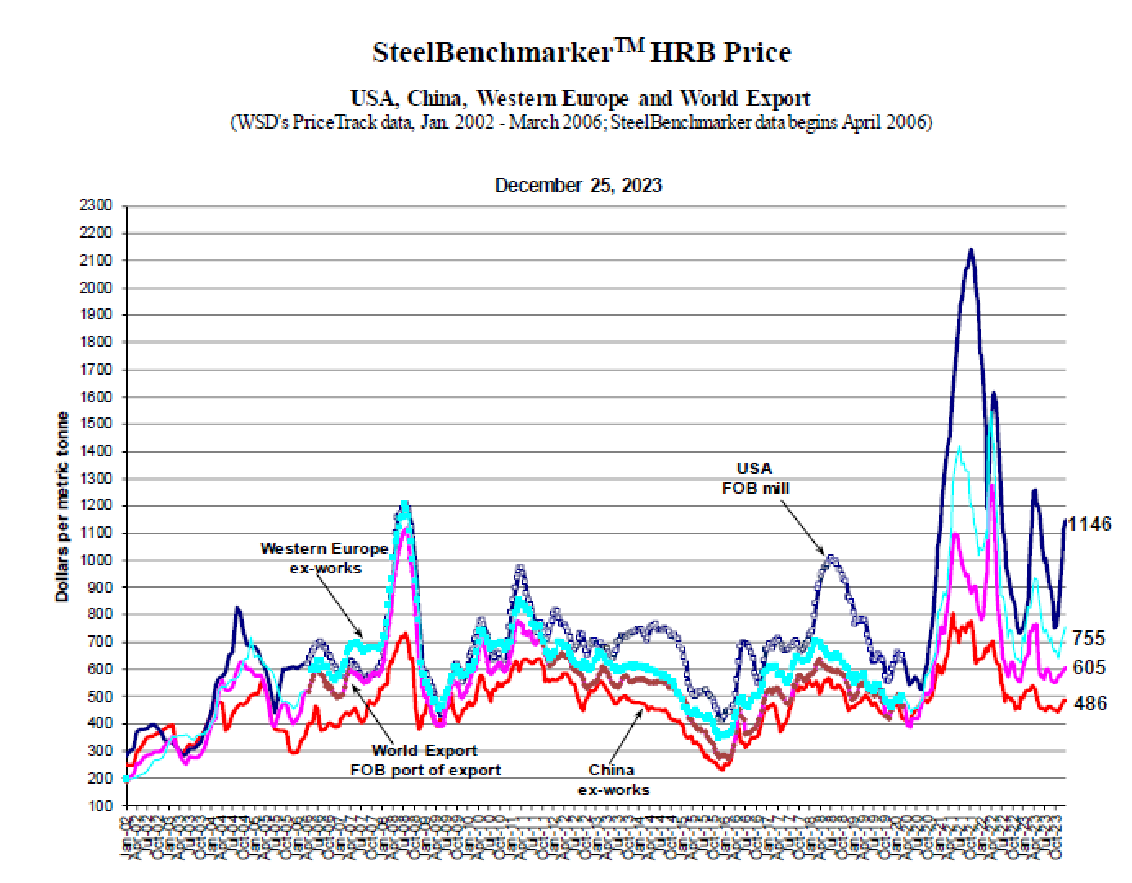

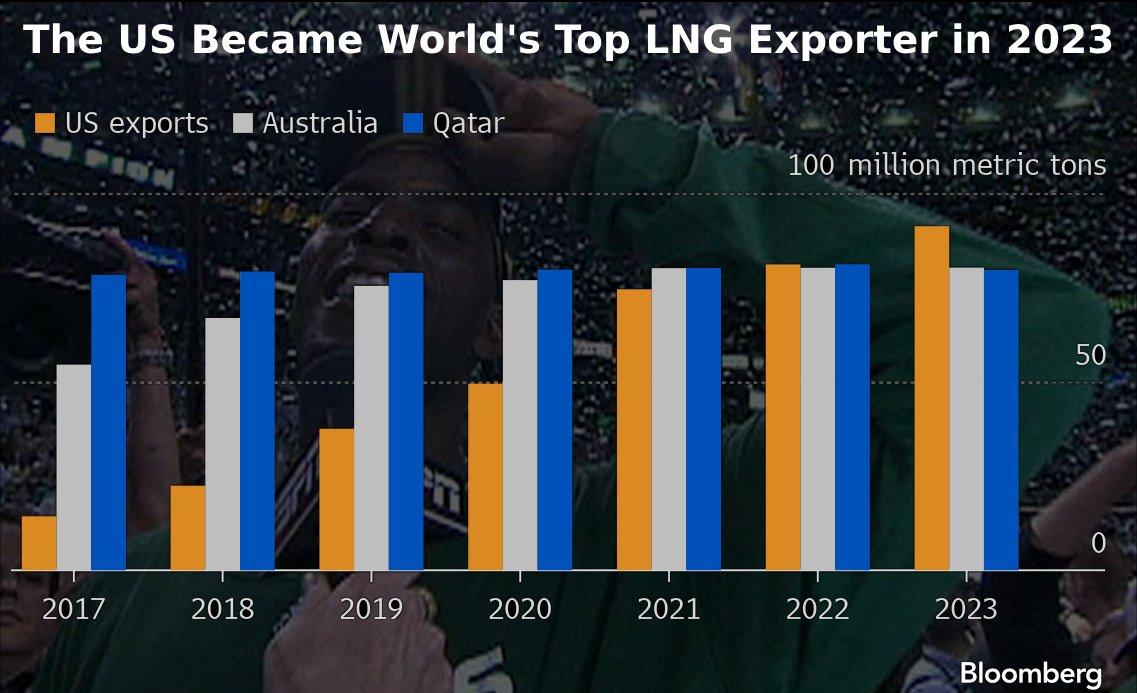

Everyone also agrees that Nippon Steel’s purchase has been driven in large part by the very economic nationalism that Vance and other critics of the deal vocally champion. As Nippon Steel executives explained and as has been widely reported, the company justified the premium it paid for U.S. Steel by pointing to two big things: First, “national security” tariffs and those hundreds of “trade remedy”measures restrict Japanese and other steel imports and keep steel prices here insanely high versus almost everywhere else in the world. Currently, hot-rolled steel is about 50 percent more expensive here than in Europe and almost double the world market price:

This situation is, as we’ve discussed repeatedly, terrible for American steel-consuming companies and the long-term health of the U.S. economy, but it’s obviously nice for the companies selling steel here and reaping windfall profits. Since Nippon Steel couldn’t easily do that with existing capacity in Japan or elsewhere, it looked to buy a U.S.-based firm instead—precisely the type of “tariff jumping” that trade experts have long studied (and that today’s protectionists have celebrated in other contexts).

Second, Nippon Steel and others anticipate a spike in domestic demand for steel caused by the subsidies and “Buy American” mandates in the three major U.S. industrial policy bills—the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act—passed into law since Biden took office. All those roads and bridges and electric vehicles and wind towers need American-made steel to qualify for the subsidies, and, per the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. iron-and-steel-mill order backlog is already at a 15-year high. Nippon Steel wants in on that action and apparently sees buying U.S. Steel as the best way to do that. Whether the move is smart or good for the U.S. economy is debatable, but their motivation surely isn’t.

As we’ve discussed, moreover, U.S. Steel was ripe for the picking thanks at least in part to this same (and other) American protectionism. I won’t rehash all that history here but do recommend the latest dives from Reason’s Eric Boehm and Brian Potter at the Institute for Progress on U.S. Steel’s longstanding prioritization of politics over innovation and repeated choice to maintain antiquated, dirty, and costly “blast furnace” production decades after steel companies abroad—rebuilding from scratch after World Wars I and II and communism—and in the United States (especially “minimill” champion Nucor) had embraced cleaner, more efficient technologies and better corporate management practices. Even after slashing its workforce and closing its worst-performing U.S. facilities, Potter notes, U.S. Steel was an industry laggard, for example adopting now-decades-old minimill technology in just the last few years (starting with its acquisition of Big River Steel in Arkansas). Other steel market experts agree.

Instead of spending billions of dollars on major technological upgrades, contract buyouts, and/or environmental remediation, U.S. Steel chose to spend a mere tens of millions on lobbying for tariffs and subsidies that kept its old facilities afloat and its domestic and international competitors at bay. As Politico reported shortly after the acquisition was announced, “U.S. Steel and its decades-long cries against allegedly unfair competition” formed the “center” of Trump administration efforts to protect the industry with tariffs back in 2018 (something those of us who were personally involved in that case know all too well).

That business model might make some financial sense (why compete or innovate when you can lobby far more cheaply?), but it’s not a recipe for a lean, mean company ready to win the future. So, when competitor Cleveland Cliffs first came calling with an unsolicited buyout offer, U.S. Steel management did just what you’d expect: It went out and found an even better offer from a deep-pocketed rival that wanted to buy not only U.S. Steel’s domestic facilities but also its somewhat-exclusive market access and its outsized political influence.

And, boy, did Nippon Steel pay up, with at least one big winner along the way—U.S. Steel shareholders and management:

Here, again, history repeats. As we discussed in 2021, past tariffs and quotas in the 1970s and 1980s allowed U.S. steel industry executives to increase shareholder returns or attract buyers for their firms. The Nippon Steel deal appears to have achieved both outcomes too, thanks to the very policies championed by the economic nationalists opposing it.

Summing It All Up

For people of a certain age, some degree of emotional resistance to Nippon Steel’s acquisition of U.S. Steel is understandable. The company still looms large in the minds of many who grew up on steady diets of Carnegie, Terry Bradshaw, Springsteen, and “mill town” nostalgia—and who probably don’t know that U.S. Steel is a husk of its former self. It’s also easy to see why some Beltway dinosaurs, including the ones who got rich in the 1980s and 1990s pushing U.S. Steel’s agenda (including against Nippon Steel!), might find the deal to be a particularly bitter pill to swallow. (Insert world’s tiniest violin solo here.)

For the rest of us, however, knee-jerk opposition to the Nippon Steel deal reeks of braindead nativism and cynical politics. Foreign investment can surely raise legitimate national security concerns in specific situations (e.g., a foreign government or state-owned company seeking to acquire a U.S. company that exclusively provides sensitive technologies to the Department of Defense), and there might be—maybe—a few defense-related products or contracts from which the New U.S. Steel may need to divest. But that’s not what we’re talking about here. Instead, we have politicians and their friends in policy and media using ludicrous economic and security concerns to try to prevent a publicly traded company headquartered in a close U.S. ally from buying an American company whose only real significance is in history books and on K Street—a transaction motivated in large part by the very policies and politics those exact same critics champion. They’ve been hoisted by their own protectionist petard and are either incapable or unwilling to see it. Neither speaks highly of them or the nationalist movement that’s supposedly taking over Washington.

Judging from the small number of critics, however, the movement’s fortunately doing no such thing.

Charts of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.