Critics of President-elect Donald Trump’s plan to deport millions of immigrants and supercharge (supposedly) manufacturing with tariffs and subsidies frequently note that the U.S. lacks the workers to enact such a plan. And a common response to that skepticism (including my own) is that there are millions of American workers—mainly men—sitting idle today, just waiting to fill the jobs that have been “taken” by immigrants or foreign manufacturers. Perhaps most famous in this regard was Trump’s running mate (and soon-to-be vice president) J.D. Vance, who, when asked by New York Times reporter Lulu Garcia-Navarro about future deportation-related labor shortages in industries like construction, explained that we could just take “the seven million prime-age men who have dropped out of the labor force” and “absolutely” get them back into the U.S. labor market after the immigrants are gone.

Vance certainly isn’t alone. Core to some protectionists' claims that tariffs would be pro-growth, for example, is that large amounts of “surplus” labor can be deployed in newly protected industries instead of simply taken from other, more productive ones. And, as I can confirm (boy can I!), the claim is also common to today’s debates about the economic implications of new U.S. limits on trade and immigration.

Upon further examination, however, the idea that there are anywhere close to 7 million men just sitting around waiting for a “good job” withers under scrutiny, as does the idea that trade and immigration are primarily to blame for the men who really are “missing” from the labor force. That latter group remains a real and significant economic concern that deserves better policy, but protectionism and nativism aren’t the answer.

Math, Again (Sorry)

It’s hard to track down the original data underlying the “7 million” number, but there appear to be two possible sources—each with big asterisks.

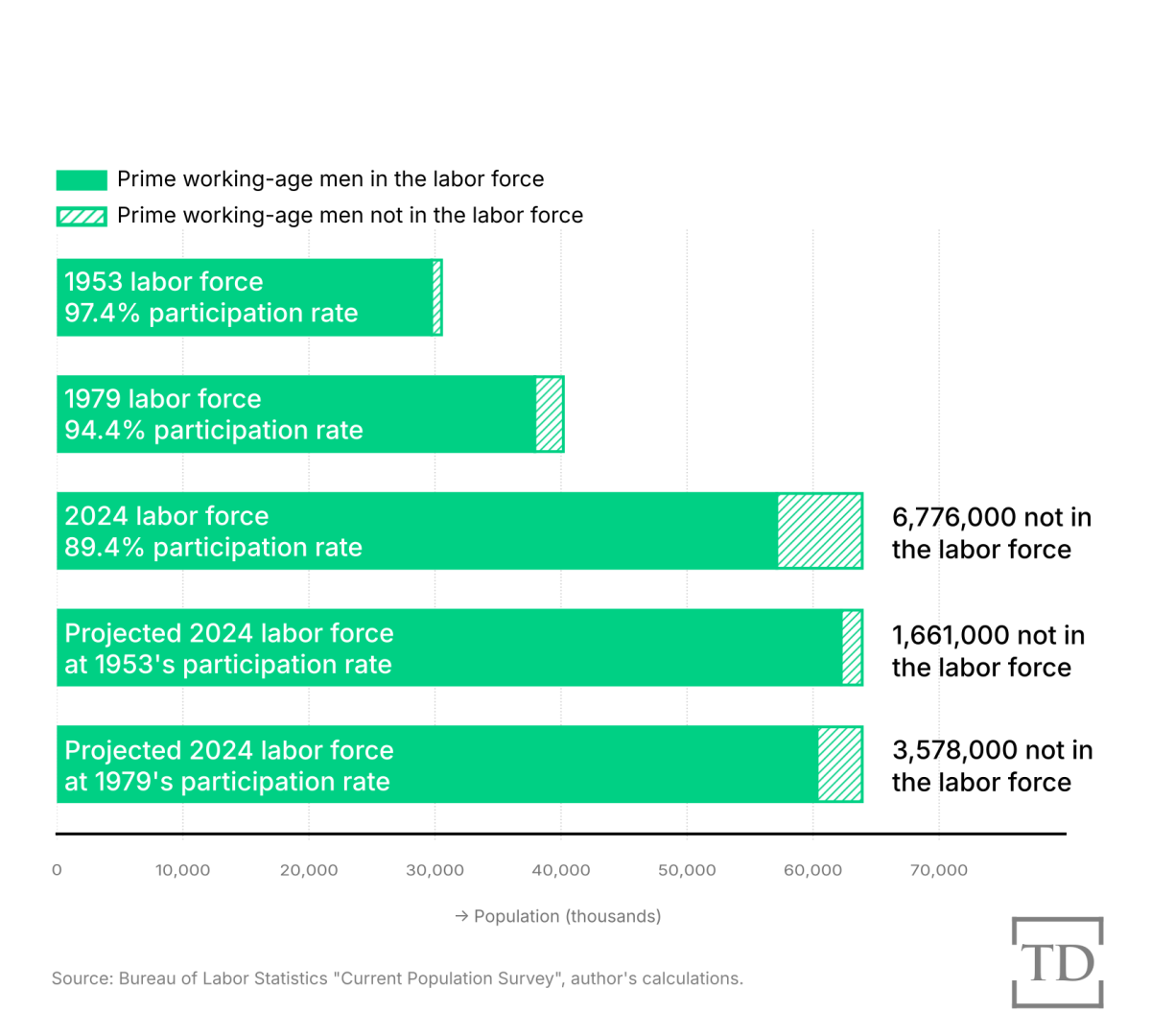

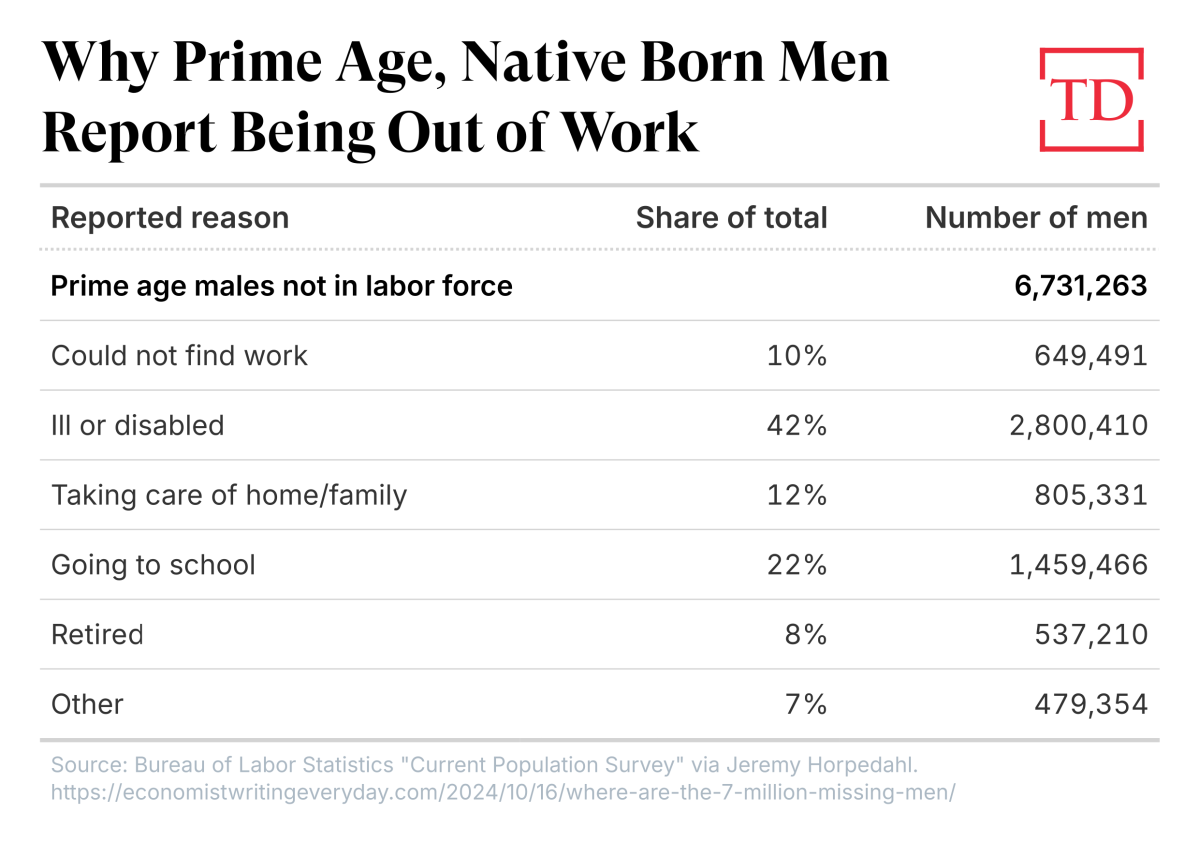

First, there’s the total number of “prime age” (25 to 54) men not in the U.S. labor force today, which can be easily pulled from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and stood at 6.84 million as of October 2024. Economist Jeremy Horpedahl, by contrast, finds a similar number of native-born, nonworking men—6.73 million, to be exact—by expanding the age range to 20- to 55-year-olds. The slightly larger BLS figure is used to determine the much-discussed male labor force participation rate (LFPR)—a rate that steadily declined from its 97-plus percent peak in the 1950s, bottomed out in 2014, and has since settled in the 89 percent range for a few years (excluding the pandemic, of course)—but the trend presumably applies to natives and non-natives alike.

From this number, however, appears the first issue with claiming “7 million” men are ready to work: Even in the “good ol’ days” of peak male labor force participation, a significant percentage of American men weren’t working for various reasons. In fact, if the prime-age male labor force participation rate were today at its absolute 1953 peak, there’d be still be around 1.7 million men out of the labor force. And if we used the lower rate from 1979—when the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs peaked—you’d more than cut the “missing 7 million” number in half (around 3.6 million).

So, even assuming we could magically apply to today the “best ever” U.S. labor market conditions for working-age males, there’d still be millions of American men not working for various reasons—men who simply wouldn’t be available to fill any new jobs (or old ones now open) generated by of a U.S. labor market that’s supposedly* more welcoming to them because of Trumpian protectionism and mass deportations. Put another way, when people rightly ask where American factories or farmers or other employers will find needed workers in our post-neoliberal Trumpian future, a “7 million” response simplistically assumes that every single working-age man not working today would be available to fill in. This simply isn’t the case—and it never has been.

(*I say supposedly here because, as we’ve discussed, protectionism and deportations might actually make the U.S. economy and labor market worse—even in male-dominated industries like manufacturing. But for our purposes today, we can ignore that very important issue.)

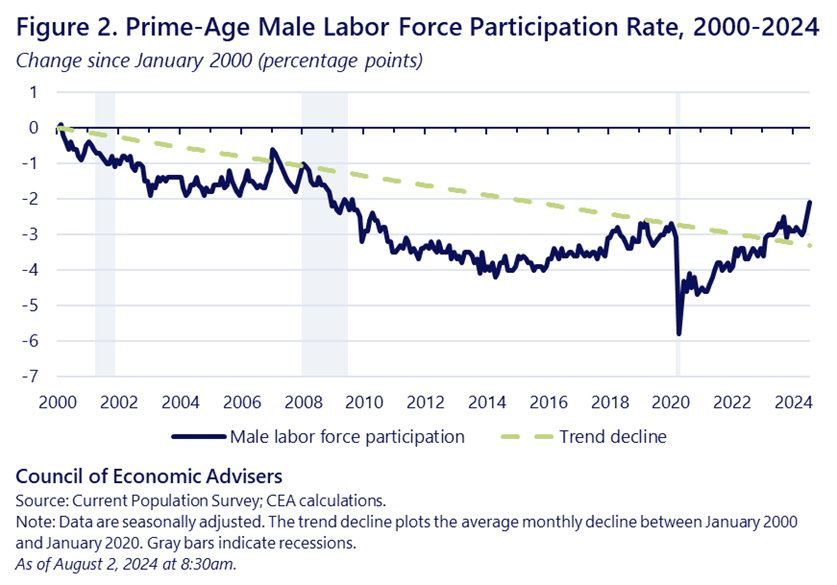

This gets to the second big problem with the 7 million men number: A significant share of “working-age” men in the United States are—and have been—out of the labor force for reasons that have nothing to do with the U.S. labor market. As we’ve discussed, the 2024 labor market is still pretty good today, and last Friday’s healthy jobs numbers reiterated this fact. According to the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, the generally positive situation extended to prime-age men, with both their labor force participation rate and employment rate at or slightly above pre-pandemic levels:

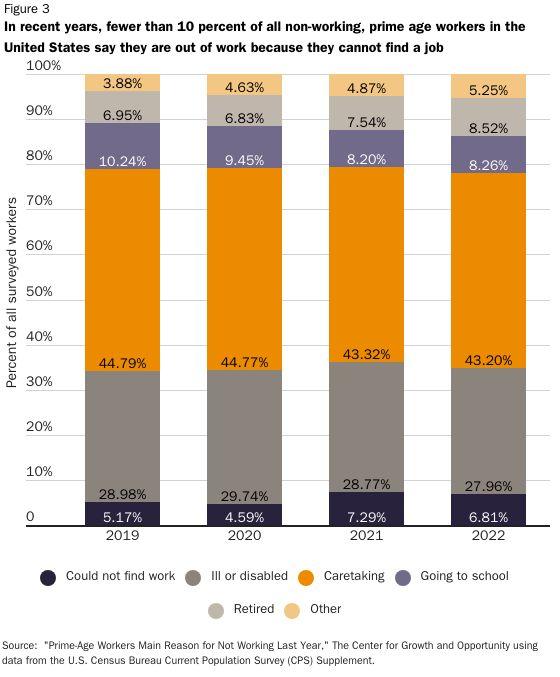

Yet even in these circumstances, BLS reports that just 10 percent of all nonworking prime-age individuals (2.1 million of 21.1 million) and 5 percent of all nonworking men (2.3 million of 42.4 million) want a job, and only a couple hundred thousand of each group are actively searching for work but “discouraged over job prospects.” This finding is generally consistent with other surveys and pre-pandemic trends, which show that very few prime-age workers are out of work because they can’t find a job and would thus be able and eager to fill new U.S. job openings:

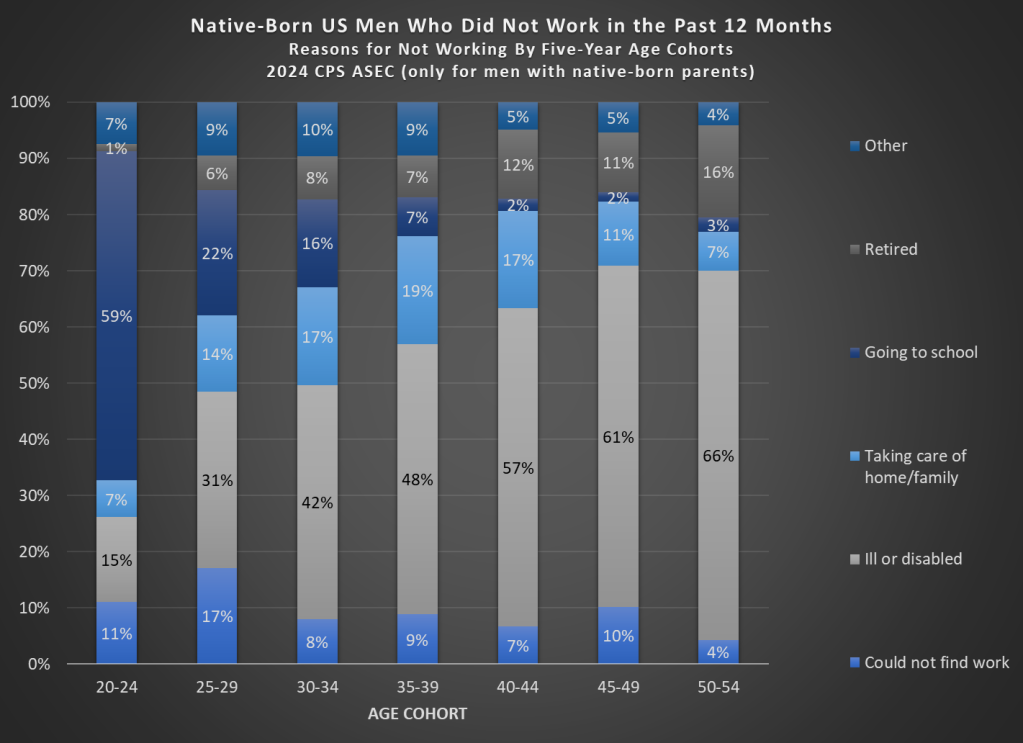

These numbers admittedly cover many people who aren’t prime-age, native-born men, but thankfully Horpedahl has sifted through the (annoyingly difficult) Census data to examine why men in this group are out of work. And he finds similar things:

Combining these men into one big cohort shows that just around 10 percent (649,000) of them report that they can’t find a job. By contrast, 42 percent (2.8 million) report being ill or disabled, 22 percent (1.46 million) in school, 12 percent (805,000) taking care of family, and 8 percent (537,000) retired.

A private survey from the Bipartisan Policy Center reiterates these results, finding that less than 5 percent of working-age men who are both unemployed and not looking for a job are in that position because they can’t find suitable employment. Once again, disability looms large in the results, while a large number simply aren’t working “by choice” (for whatever reason). In looking at these and other data, AEI’s labor market guru Scott Winship concludes that declining male labor force participation simply “hasn't been due to any deterioration in the labor market or economy.”

One can question whether these millions of “disabled” male workers really are disabled (more on that in a sec), but the results still leave millions of working-age men on the sidelines for perfectly legitimate, noneconomic reasons. As Horpedahl put it, “even if we could wave a magical wand and cure all of the men that are ill or disabled, this would add less than 3 million people to the labor force”—far from the 7 million that Vance and others claim. And, of course, many of these men actually are sick or disabled.

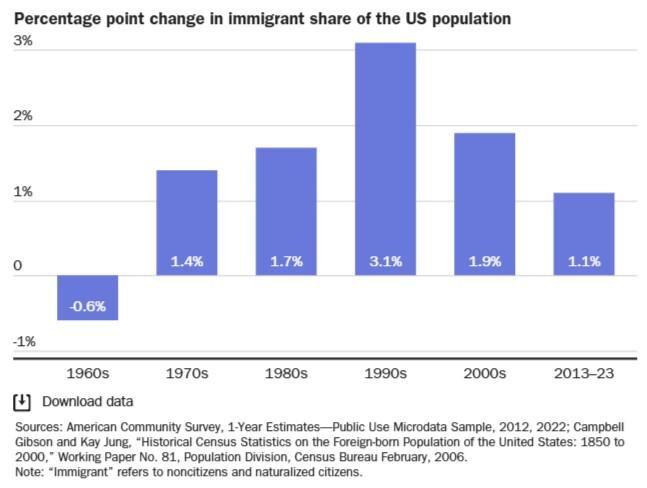

Immigrants and Trade Aren’t the Main Problem

Finally, there’s little hard evidence that male labor force participation is being broadly depressed by the United States having too many immigrants or too few manufacturing jobs. As Reason’s Eric Boehm wrote a couple of months ago, the work of AEI’s Nicolas Eberstadt—a top expert on male nonparticipation—shows that “the decline in work force participation of American men has been steady and ongoing since the 1960s … during periods when immigration has been high, and when it has been low.” Here’s a useful chart in this regard:

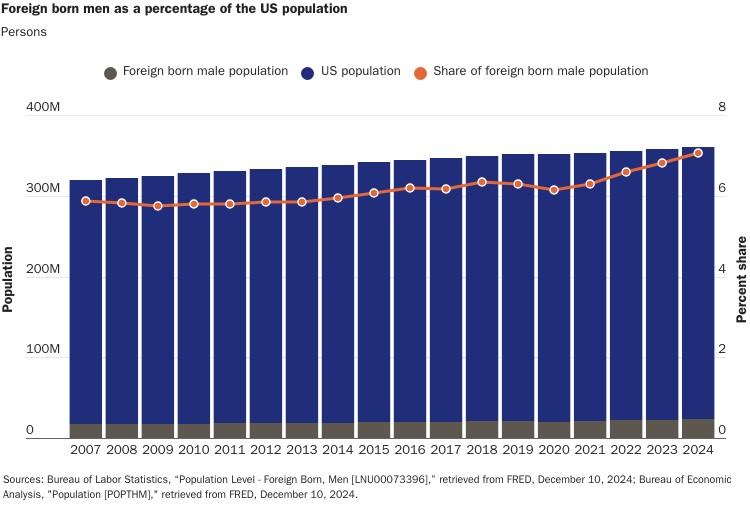

More recent data on male immigrants show a similar lack of correlation. In fact, the recent, admittedly modest rebounds in the male labor force participation rate and employment rate have coincided with an also-modest increase in the population’s share of foreign-born men:

Blaming trade is similarly weak, Boehm adds, quoting Eberstadt himself from 2020 (emphasis mine):

The tempo of workforce withdrawal appears to be almost completely unaffected by the tempo of national economic growth, which varied appreciably over this period. Even recessions—including the Great Recession—appear to have scarcely any impact on the trend. Likewise, the NAFTA agreement, China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, and other ‘disruptive’ trade events with major implications for the demand for labor in America do not stand out.

More recent data, per economist Jon Murphy, tell a similar story on the trade front. Today, there are still about 500,000 job openings in manufacturing—down from the number’s post-pandemic high but still well above its pre-pandemic average (293,000) and a number that’s been “generally rising” for decades. Layoffs in the manufacturing sector are also “very low” and have been that way since 2001 (when China joined the WTO), and wages have generally been rising faster than inflation (indicating persistent demand for workers). If somehow “deindustrialization” were keeping manufacturing labor demand low and, in turn, keeping American men out of the labor market, we’d expect the opposite trends.

What Is to Blame?

So, there are probably far fewer than 7 million sidelined men out there, and most of the men who are really sidelined are probably that way for reasons other than U.S. immigration or trade policy. For a significant chunk of those that remain, moreover, nonparticipation probably has little (if anything) to do with policy of any sort. Practical barriers to their working—geography, job type, qualifications, desire, etc.—surely play a role, and cultural resistance to certain kinds of work (see, e.g., here and here) might too. The U.S. government (fortunately) also can’t force someone to work if they really don’t want to—a hurdle that’s particularly relevant as American houses get bigger (more parents’ basements!) and leisure gets cheaper.

These points, however, don’t mean that there are no problems with male labor force nonparticipation today, or that various policies aren’t playing a meaningful role in keeping men (and women) out of the workforce. We can reasonably assume, I think, that the real number of discouraged working-age men is more than the 650,000 or so who are telling the government that, and the survey’s “other” category alone adds another 480,000. This group can, in turn, have concerning social, political, and economic implications worth addressing.

As detailed in my 2023 book, moreover, there really are federal, state, and government policies that either encourage nonwork or discourage (or even prevent) men from taking jobs that they want. Occupational licensing laws, for example, block many men from entering professions—including several blue-collar ones—without first enduring a lengthy and costly application process. (See, for example, this brand new report on how Connecticut’s insane construction licensing laws contribute to the state’s lack of construction workers.) Misguided criminal justice policies, meanwhile, contribute to the fact that there are today hundreds of thousands of men not working because of their criminal records (though of course not every guy with a record deserves to be free of it and quickly reintegrated into the workforce). And when licenses are denied to people with records, the policies can work together to keep people—men and women—out of the labor market.

Welfare policy can also play a role, most notably by paying able-bodied men not to work or otherwise discouraging their participation in the formal economy. Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), for example, can allow many people who should be working to instead go on disability, especially when the economy is poor. According to one recent paper, high unemployment during the Great Recession “induced nearly one million SSDI applications that otherwise would not have been filed, of which 41.8% were awarded benefits, resulting in over 400,000 new beneficiaries who made up 8.9% of all SSDI entrants between 2008 and 2012.” Since then, policy reforms and a good economy have modestly reduced caseloads, contributing to the rebound in male labor force participation. But more should be done.

Policy can also discourage men from moving to work, especially across state lines. Licensed workers in one state, for example, often can’t legally work in another state, while transportation policy makes the trip more expensive. Housing policy, by artificially inflating home prices and rents in many high-growth places with lots of jobs, also makes it harder for lower-income Americans to move for work. Various welfare programs tie people to certain places because benefits are offered as in-kind payments (e.g., housing assistance) or paid by a specific state or local agency. And education policy also looms large: Eberstadt himself cites “a lack of educational options for low-income men” as the “primary cause” of their nonwork (along with welfare and criminal justice policy).

Summing It All Up

Contrary to common nationalist claims, it’s simply implausible that there are anywhere close to 7 million working-age American men just itching to jump into the U.S. labor market should future President Donald Trump somehow make millions of immigrants and billions in imports quickly disappear. Given various survey results, in fact, a large majority of that 7 million isn’t working today for reasons unrelated to the labor market, and—barring a serious life change—is unwilling or unable to hop back in tomorrow. Even discounting some of the survey responses (especially on disability), the real number of “missing” American men is probably a small fraction of the total number not working today.

Pushing back on the 7 million men narrative is about more than just nitpicking the exact number. It’s critical to understanding a big, practical reason why mass deportations and widescale protectionism won’t usher in a new era of Trumpian prosperity: Without a vast reserve of available American workers, U.S. companies will struggle to replace newly deported immigrants or expand into newly protected industries, and that will—barring a robot/AI revolution!—act as a hard limit on future economic expansion, especially as policy diverts already employed workers from more productive enterprises to less-productive ones (like making T-shirts or toasters). Skepticism of such plans certainly runs deeper than simply asking “who will build the houses and man the factories,” but the question remains a perfectly fine and important place to start.

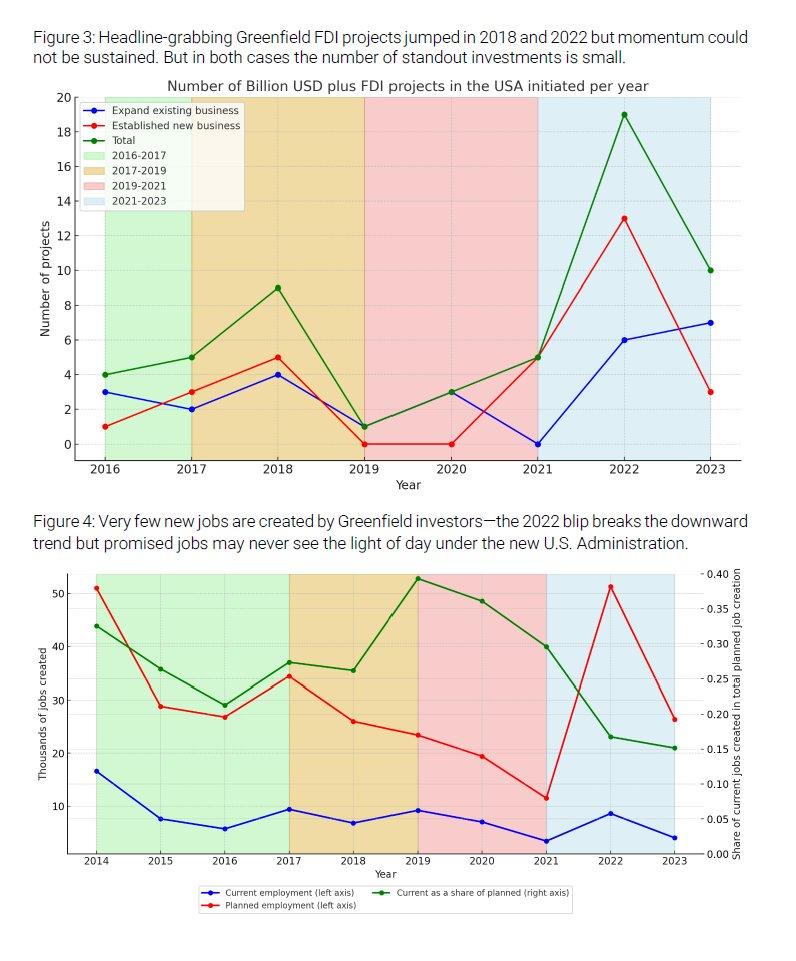

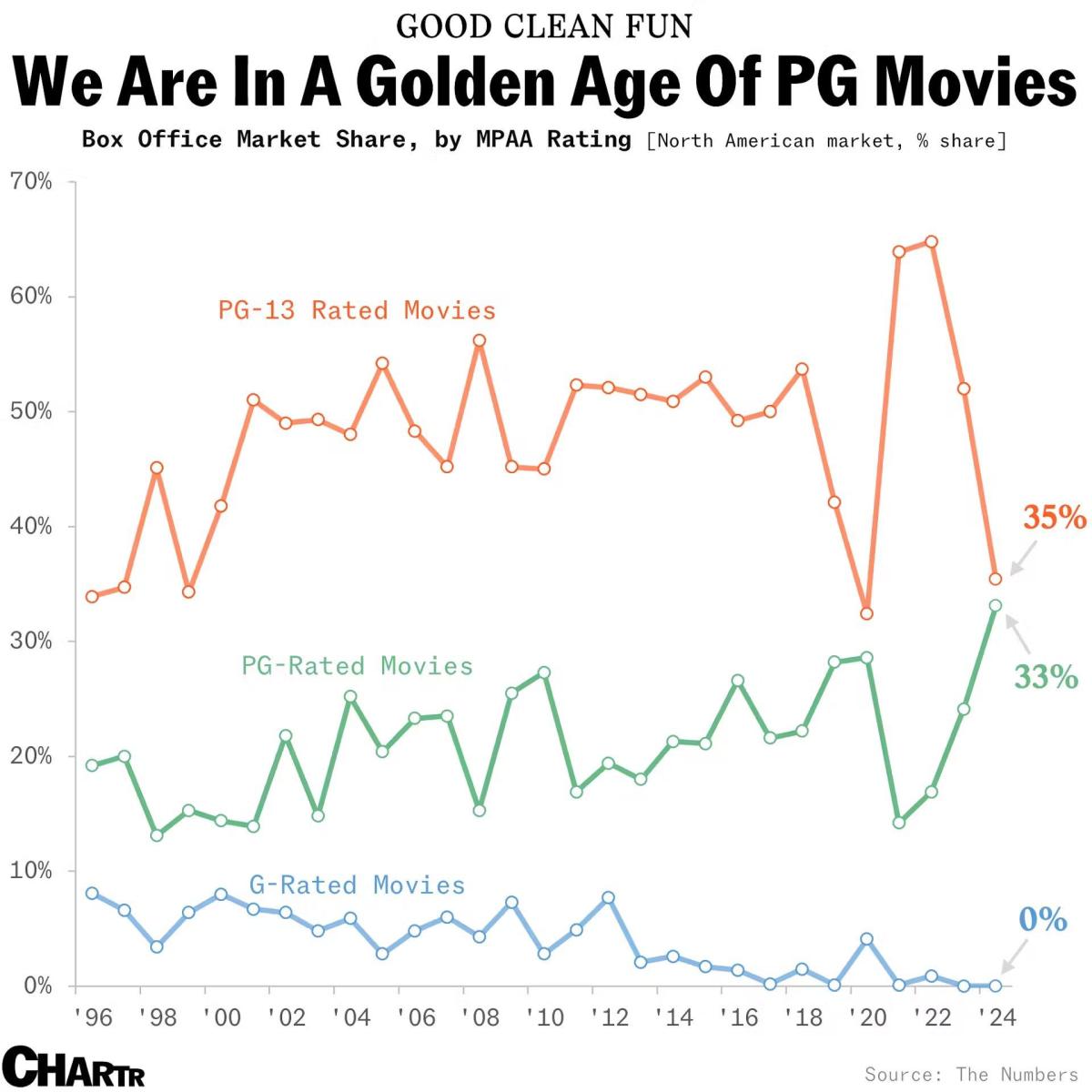

Charts of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.