Dear Capitolisters,

In case you haven’t noticed (and if you’re reading this you probably have), Donald Trump’s meteoric rise and persistent influence on U.S. politics has created an identity crisis on much of the American right. In particular, there is tension between more traditional “Reaganite” conservatives and a “new right” group of “national conservatives” more in Trump’s mold. In recent years, the energy—more in rhetoric and attention than concrete policy wins and major electoral victories—has been squarely with the latter group, which released last year a 10-point “Statement of Principles” signed by various natcon wonks and pundits. For more than a year, the Natcon Manifesto had the stage to itself, discussed and debated, sure, but not directly challenged by an alternative vision for the future of the American right. That vacuum was filled two weeks ago when a new group, the “freedom conservatives,” published their own mission statement, which—although expressly not intended to be an “anti-Natcon” document (see also this accompanying op-ed by John Hood)—nevertheless offers a conservative alternative what the natcons are selling.

I didn’t sign the freecon document and can quibble with certain elements and omissions, but I know and respect many of the signatories—including The Dispatch’s own Jonah Goldberg and Kevin Williamson—and prefer it greatly over the natcon alternative, as frequent Capitolism readers could surely guess. Were this a world of binary choices, your humble, free-market, lowercase-L libertarian correspondent would choose the freecons in a heartbeat (and twice on Sundays).

But today’s column is less about my choice and more about whether the dueling statements offer much of a choice at all, or whether they are—as some more thoughtful internet commentators have since asserted—simply different points along the same conservative spectrum, separated by modest and marginal policy differences instead of a gaping philosophical chasm. In this reading, the two statements, and the groups they represent, share the same objectives and political adversaries—the woke left, a captured administrative state, compromised corporatists, and so on—and, save a few major policy breaks (mainly trade and immigration) or imprecise/emotional words here and there—really just disagree about where wonky policy lines should be drawn. In short, it’s all shades of the same conservatism—shades that only the dorkiest of politico will care about.

This view, I think, really misses the mark. Indeed, even a cursory look at the two statements reveals a foundational, unbridgeable gap between natcons and freecons on the role of the government—especially the federal government—in American politics and American life. And it’s that difference, in turn, from which the policy differences (and there are many) are derived.

Who’s Serving Whom?

Let’s start with the natcons’ statement, which offers a vision for America that expressly puts the state, not its people, at the center of the action. The document, in fact, begins by declaring that the signatories “emphasize the idea of the nation” because only nations (“each pursuing its own national interests and upholding national traditions that are its own”) are a “genuine alternative” to the “universalist ideologies” they oppose. The rest of the document continues this statist (for lack of a better word?) theme: The first and second principles, on “National Independence” and “Rejection of Imperialism and Globalism,” respectively, address only state action and reference actual people—individuals, families, etc.—only once (and in relation to the state). In Principle 1, in fact, the state has a “right” to maintain borders and conduct policy, while in Principle 2 it is “nation-states”—not people—who work “together through trade treaties, defensive alliances, and other common projects.” (Wonky aside, governments don’t trade; people do; and trade agreements just regulate—or deregulate—how people do that. Anyway, back to the show.)

The theme is continued in Principle 3, on “National Government,” which mentions liberty, freedom, and limited government (hooray), but repeatedly qualifies and limits those principles via an empowered government. They believe, for example (emphasis mine), in a “strong but limited” state; they want a “drastic reduction in the scope of the administrative state” (but not its overall size?); they recommend federalism and decentralized state power to expand freedom, but then add an exception you could drive a tank (ahem) through: “in those states or subdivisions in which law and justice have been manifestly corrupted, or in which lawlessness, immorality, and dissolution reign, national government must intervene energetically to restore order.” These broad terms, of course, are undefined.

Principle 4 again prioritizes the “nation” when advocating public religion (i.e., Christianity, at least where there’s a Christian majority). It kindly permits religious minorities to freely observe their own traditions (in certain settings: “communal institutions” and child-rearing), and ensures that people are free “from religious or ideological coercion”—though only “in their private lives and in their homes.” Principle 5 supports the rule of law but clarifies that it’s “how we preserve our national traditions and our nation itself” (again, emphasis mine). We finally get around to “Free Enterprise” and “individual liberty” in Principle 6, and once again these things are subject to massive caveats and exceptions that authorize, if not prioritize, state action in the (undefined) “national interest.” This part deserves to be quoted in full:

But the free market cannot be absolute. Economic policy must serve the general welfare of the nation. Today, globalized markets allow hostile foreign powers to despoil America and other countries of their manufacturing capacity, weakening them economically and dividing them internally. At the same time, trans-national corporations showing little loyalty to any nation damage public life by censoring political speech, flooding the country with dangerous and addictive substances and pornography, and promoting obsessive, destructive personal habits. A prudent national economic policy should promote free enterprise, but it must also mitigate threats to the national interest, aggressively pursue economic independence from hostile powers, nurture industries crucial for national defense, and restore and upgrade manufacturing capabilities critical to the public welfare. Crony capitalism, the selective promotion of corporate profit-making by organs of state power, should be energetically exposed and opposed.

Well, you might say, at least they’re attacking crony capitalism and corporatism. Alas, we then move on to Principle 7, which advocates for that very thing, i.e., government programs to “focus large-scale public resources on scientific and technological research with military applications, on restoring and upgrading national manufacturing capacity, and on education in the physical sciences and engineering.” Corporations, of course, would spearhead this work—indeed, they’d deny the funds to “most universities,” unless they “rededicate themselves to the national interest.” Education policy, meanwhile, also “should serve manifest national needs.”

I could go on, but I think you get the idea. This is “nationalism” in its most literal sense. L'état, c'est nous.

With this context, one can more clearly see how the freecon statement is fundamentally different from its natcon counterpart. Principles 1 and 2 lead off by focusing on human beings, not the state:

Liberty. Among Americans’ most fundamental rights is the right to be free from the restrictions of arbitrary force: a right that, in turn, derives from the inseparability of free will from what it means to be human. Liberty is indivisible, and political freedom cannot long exist without economic freedom.

The pursuit of happiness. Most individuals are happiest in loving families, and within stable and prosperous communities in which parents are free to engage in meaningful work, and to raise and educate their children according to their values.

You may not agree with the line about families (these are conservatives, after all), but the emphasis here is clearly on people—the state/nation is as yet unmentioned (though perhaps implicitly referenced in the part about “arbitrary force”)—and is a stark contrast to the natcon priorities. The contrast on education—serving the state (natcon) or parents’ values (freecon)—may be the most telling example of all.

Freecon Principle 3 continues the theme, prioritizing free enterprise (the “foundation of prosperity”) and decrying “government intervention and private cronyism” that makes Americans’ lives unaffordable. Beyond that, the state is again omitted, and while certain terms have some wiggle room (e.g., “free trade with free people”) that might permit government interference, the emphasis is clearly on private action, human freedom, and limits on government action. Principles 4 and 5 then address that action more directly, but only as advocating limits thereon: in particular, fiscal responsibility and the rule of law. Principle 6 is on immigration, and while not nearly enough of a full-throated embrace of expanded immigration for my tastes, it again makes clear that policy should be implemented to “advance the interests and values of American citizens”—not the “nation-state.” Principle 7 supports federalism in an almost-unqualified manner. Principles 8 (on race) and 10 (on speech and belief) again emphasize individual and economic freedom. And it’s only Principle 9—on foreign policy—that ever mentions a national interest (“American foreign policy must be judged by one criterion above all: its service to the just interests of the United States.”), but, even then, freedom and individual liberty are mentioned.

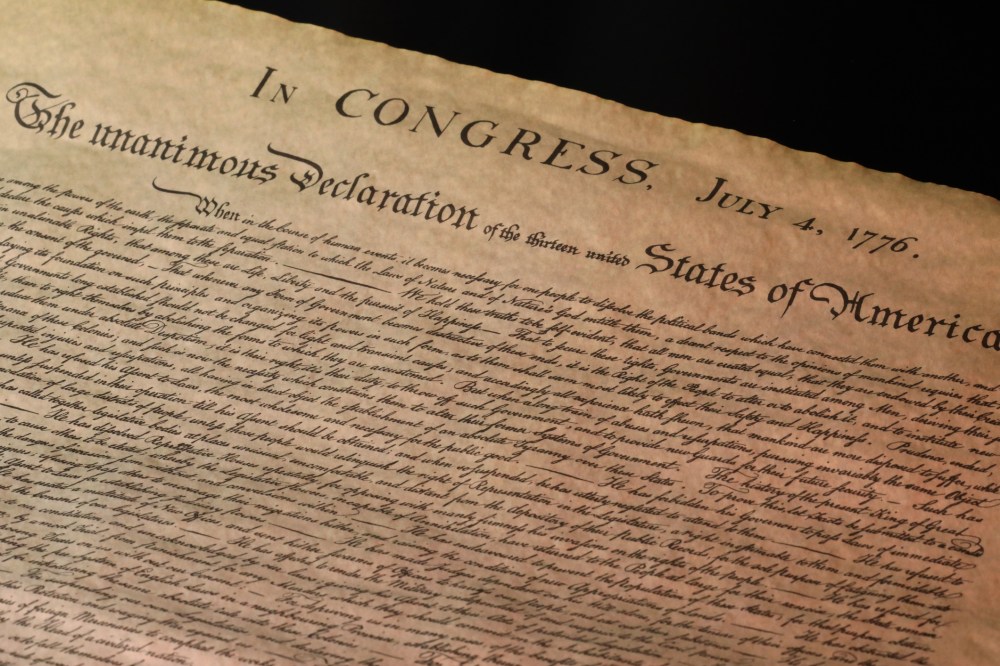

From all of this, clear and fundamental differences emerge between these two groups on the relationship between the state and the individual, and the role of each in American politics and life. In the natcon document, the state—the “national interest”—is first (and anthropomorphized), and the people are a distant second (“liberty” and “freedom” are even lower, but that’s a discussion for another time). Freecons take the exact opposite approach: their default human liberty, and state action is the (limited) exception. They prioritize—as the Declaration of Independence did—individual rights and the primacy of the people over their government:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

This is also, of course, a classically conservative view of American government and the nation’s founding. As George Will (another freecon signatory) explained a few years ago, the Declaration guided the Constitution’s framers when they created “an institutional architecture that would achieve their intention: to establish governance that accords with the common sense of their time, which was that government is properly instituted to ‘secure’ the preexisting natural rights referenced in the Declaration.” Matthew Continetti, who wrote a recent book on the American right, adds that the freecon statement is perhaps most remarkable in “that it had to be written at all” because conservatives since the 1930s have “placed freedom at the heart of their political program”—a program resistant to control by centralized bureaucracies; supportive of constitutionally limited government, free markets, individual choice and competition; anchored on the American founding and an individualistic culture suspicious of authority; and almost universally concerned about the dangers of “unconstrained government.” (And, I should add, for good reason.)

In any statements like these, there’s an inevitable amount of strategic ambiguity to entice signatories and commenters. But, even with the usual fuzziness, the freecons’ overall messages—and their fundamental difference from the natcons (whose statement omits the Declaration entirely)—couldn’t be clearer. As Hood put it in his op-ed: “We think Washington has too much power and our states, communities, private associations, and household[s] have too little.” How many natcons would agree with that?

Not so many, I’d guess. Indeed, here’s Sen. J.D. Vance—obviously not a natcon spokesman but still one of their champions—in 2021 (emphasis mine):

So a lot of conservatives have said we should deconstruct the administrative state. We should basically eliminate the administrative state. And I'm sympathetic to that project, but another option is that we should just seize the administrative state for our own purposes. We should fire all of the people. I think Trump is gonna run again in 2024. I think he'll probably win again in 2024, and he'll win by a margin such that he'll be the president of the United States in January of 2025. I think what Trump should do, if I was giving him one piece of advice: Fire every single mid-level bureaucrat. Every civil servant in the administrative state. Replace them with our people, and when the courts—because you will get taken to court—and when the courts stop you, stand before the country like Andrew Jackson did, and say, “The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.”

Elsewhere he was even more blunt: "If we're going to actually really effect real change in the country, it will require us completely replacing the existing ruling class with another ruling class." As Avik Roy documents over at National Review (and as others have done for a while now), Vance is not the only natcon with this view. So, while Vance’s take might not be a consensus or even majority “natcon” opinion, it’s most definitely one that their mission statement—and its prioritization of the “national interest”—permits. Would the freecon statement do the same? Most definitely not.

And This Inevitably Affects Policy

This distinction is not merely rhetorical—it drives big differences in how natcons and freecons approach and craft public policy, with the former taking a far more expansive—indeed, progressive—view of where and how the federal government may and should intervene on various policy issues. This includes, by the way, issues and entities about which many freecons are also quite concerned—things that most freecons agree are a nationwide problem but wouldn’t ever condone bringing the government into the matter. Roy gets at some of this in his piece, highlighting that, while he shares natcons’ concerns about cronyism, corporate power, and Chinese government influence, freecon solutions center on freedom, markets, and both constitutional and pragmatic limits on government action. Natcons’ first instinct, on the other hand, is seizing and using state power.

That embrace, it should be noted, goes well beyond federalism and the administrative state—and beyond discrete policy issues like immigration, trade, or industrial policy. Indeed, seemingly wherever there’s a perceived enemy (Big Tech, Wall Street, “the left”, etc.) or problem (economic or cultural) challenging the (undefined) “national interest,” natcons’ eager default response is to enlist the government to address it. Here are ones I can think of just off the top of my head: Tech policy (e.g., Section 230); corporate speech (e.g, Disney/Florida, social media, ESG); antitrust; education (especially “anti-woke” stuff); financial regulation (e.g., buybacks and “financialization”); labor policy (e.g., at Amazon); transportation policy (e.g., the Railway Safety Act); family policy (e.g., child allowances); and entitlements (sigh).

If this is “conservative government,” I’d hate to see what the progressive version is.

More seriously, much of this policy is progressive, as natcon politicians frequently join with their left-leaning (if not far-left) colleagues to advance legislation along these policy lines. My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne, in fact, has collected numerous examples—Vance and Bernie Sanders on trade with developing countries; Josh Hawley and Amy Klobuchar on antitrust and the “Gilded Age”; Marco Rubio and Sherrod Brown on stock buybacks; Tom Cotton and Jared Bernstein on industrial policy; Tucker Carlson and Elizabeth Warren on the “free market”—of natcons and card-carrying progressives talking about policy in utterly indistinguishable ways. That’s not a coincidence; it stems from natcons’ sharing with progressives views on not only discrete policy, but on the role and power of government itself. And when they do debate and disagree, it’s (usually) on whom the state should support (or fight), not whether it should act at all.

The latter question is where almost all conservatives used to chime in, and freecons would presumably do so in the future.

Summing It All Up

The freecon manifesto isn’t perfect—I have my own disagreements, as do other libertarians and old-school conservatives (including Continetti). But there’s plenty in there to like—for a libertarian, classical liberal, or any other fan of the Declaration’s principles and constitutionally limited government–especially when compared to the statist natcon alternative. These aren’t shades of gray in the same conservative newspaper, and the disagreements aren’t just on a handful of backpage policy issues. Instead, it’s the fundamental differences between natcons and freecons that drive their policy differences, not the other way around. I don’t know which side the American right will ultimately choose, but it’s most definitely a choice—and a very big one at that.

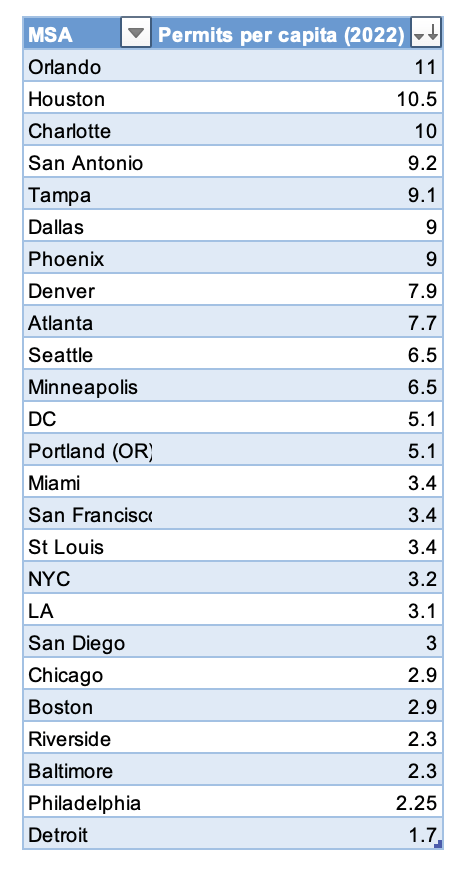

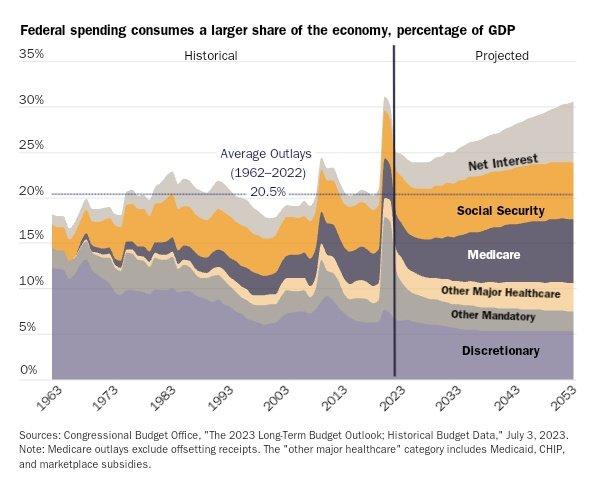

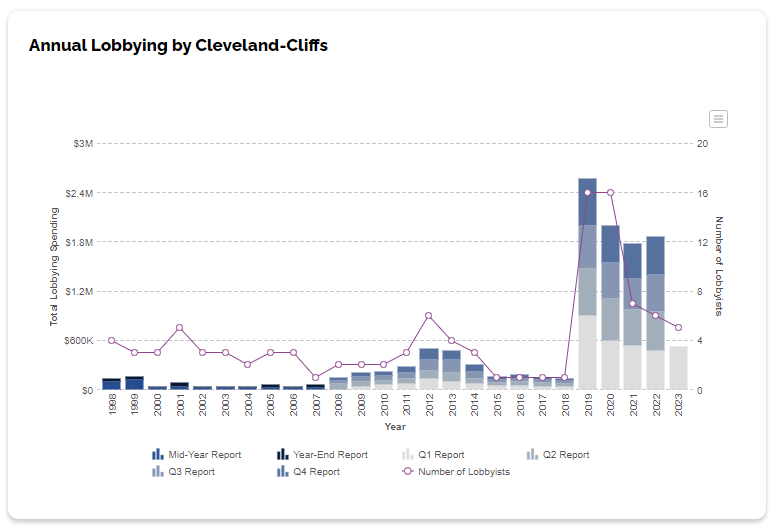

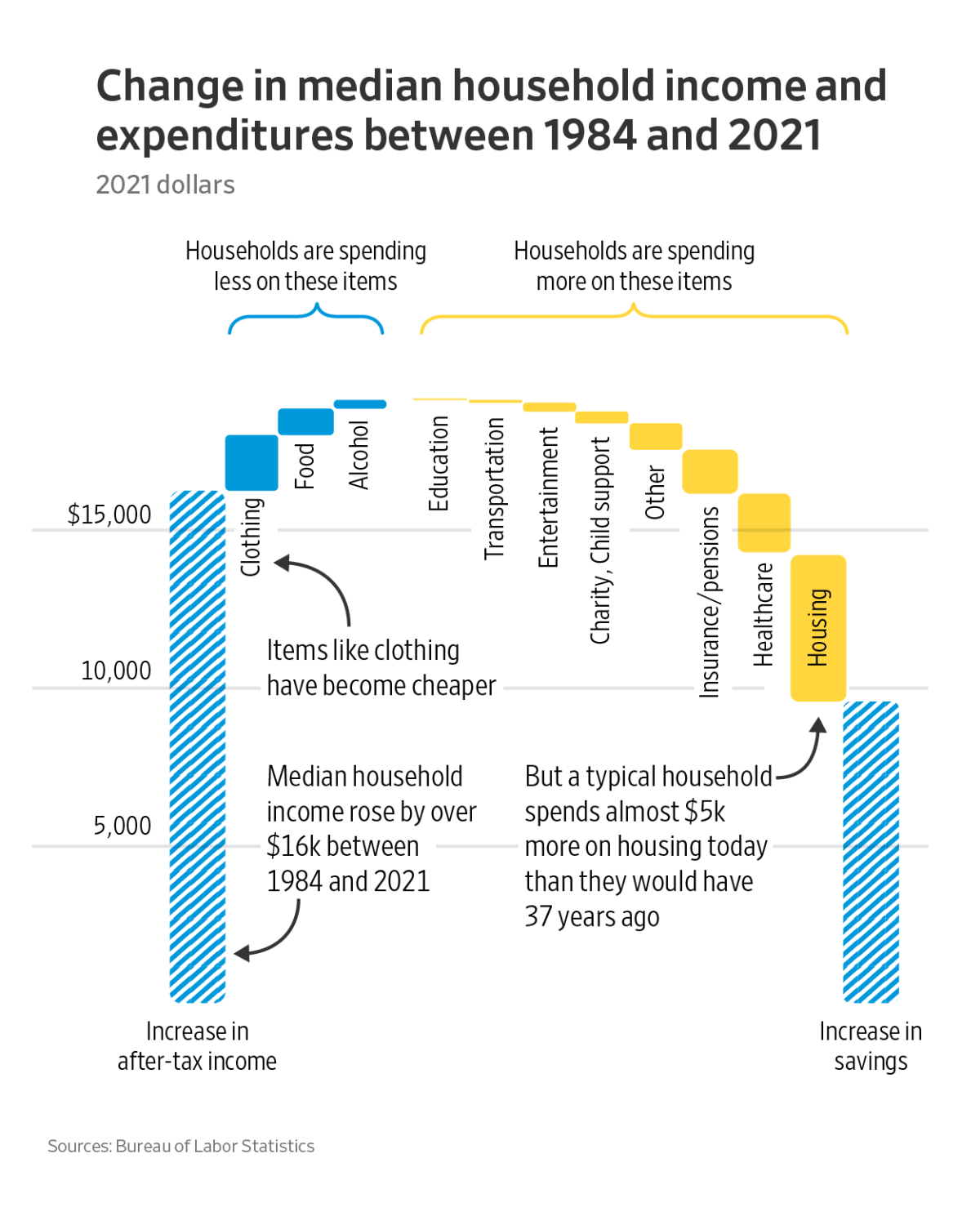

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.