Dear Capitolisters,

I often start outlining my weekly column on the Saturday before it’s due—just jotting down various notes and links as my coffee-soaked neurons fire off into all directions. Things in Ukraine, however, have confounded that process, as new events cannibalize their predecessors. So, instead of giving you some detailed hot take about the current moment, today I’m going to provide a somewhat random list of early observations that, I hope, will inform your thinking about these events (in which—let’s face it—U.S. economic policy plays, at best, a secondary role).

Economic Impact

The question I’ve been asked most in the last few days (including by my mom) is how this war might affect the U.S. economy. This, I’m afraid to say, is tricky. On the one hand, the direct economic impact of the conflict and of U.S. and global sanctions—together cutting off most trade and capital flows between the United States and both Russia (sanctions) and Ukraine (war)—should be relatively minor. According to the office of the U.S. trade representative, for example, total trade U.S. trade with Russia was a meager $34.9 billion in 2019; bilateral investment flows (inward and outward) were another $18.8 billion that year; and sales by overseas affiliates in each country were $10.3 billion in 2017 (the last year available). These same figures for Ukraine were even smaller (less than $5 billion in total trade and investment in 2019). This might sound like a lot—and disruptions will surely affect some particularly-exposed companies—but, overall, this is little more than a rounding error for a $23 trillion U.S. economy.

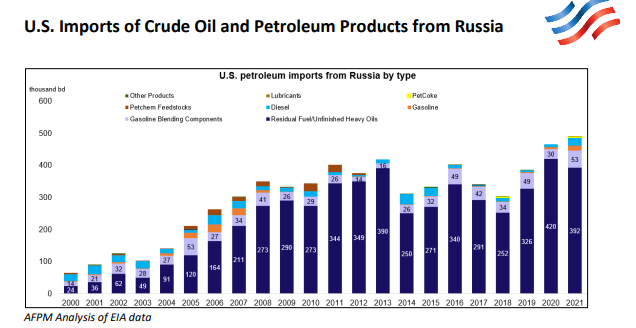

Even in energy goods trade (which hasn’t been banned—yet), there isn’t a huge area for concern. For example, “2021 crude imports from Russia averaged 0.2 million barrels per day, the highest level in many years, but still a small share of total imports and total crude oil processed by U.S. refineries (~1%).” Even when you add in other petroleum products, it’s only about 700,000 barrels per day. With about 357,000 of those barrels going to U.S. refineries as unfinished oils, you’re still only looking at Russian oil supporting about 3 percent of total U.S. refinery consumption (for stuff like gasoline)—and that was before U.S. importers started “self-sanctioning” themselves away from Russian crude.

Of course, there’s a lot more to the situation than just these bilateral trade and capital flows—and that’s where the questions and concerns arise. For starters, while Russia is a minor player in global trade too (between 1 and 2 percent of global GDP and trade), it is a major energy and wheat exporter—second only to the U.S. in global oil and gas trade and often first in wheat. Ukraine, meanwhile, is also a major grain exporter—second largest in the world. Though most of these supplies go to places other than the United States, global commodities markets are—well—global, meaning that real or anticipated reductions in supplies of these commodities in one place can lead to higher prices in others. Bloomberg gives one example of how: “Any disruptions to [grain] flows would quickly ripple through to buyers in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, boosting costs for bread and meat and potentially increasing demand for supplies from the Americas or Europe.” Thus, global oil price benchmarks (including the U.S.-based West Texas Intermediate) broke $100 a barrel yesterday, and wheat, soybean, and vegetable oil prices are “near unprecedented levels.”

Drilling (pun!) into oil and gas a little more, there’s bad news and good. On the former, while high prices are pushing some frackers back into the oil patch, energy expert Bob McNally recently notes that there really aren’t any “quick fixes” (e.g., leveraging the relatively small strategic petroleum reserve and substantially boosting U.S. production) here. Indeed, the just-announced release of 60 million barrels from global strategic reserves is only about 5 days of U.S. crude oil production and less than a single day of global consumption—a literal drop in the bucket. U.S. bans on oil imports or exports won’t help matters either, and might actually make things worse by discouraging more domestic drilling and perhaps also encouraging foreign countries to impose their own export bans.

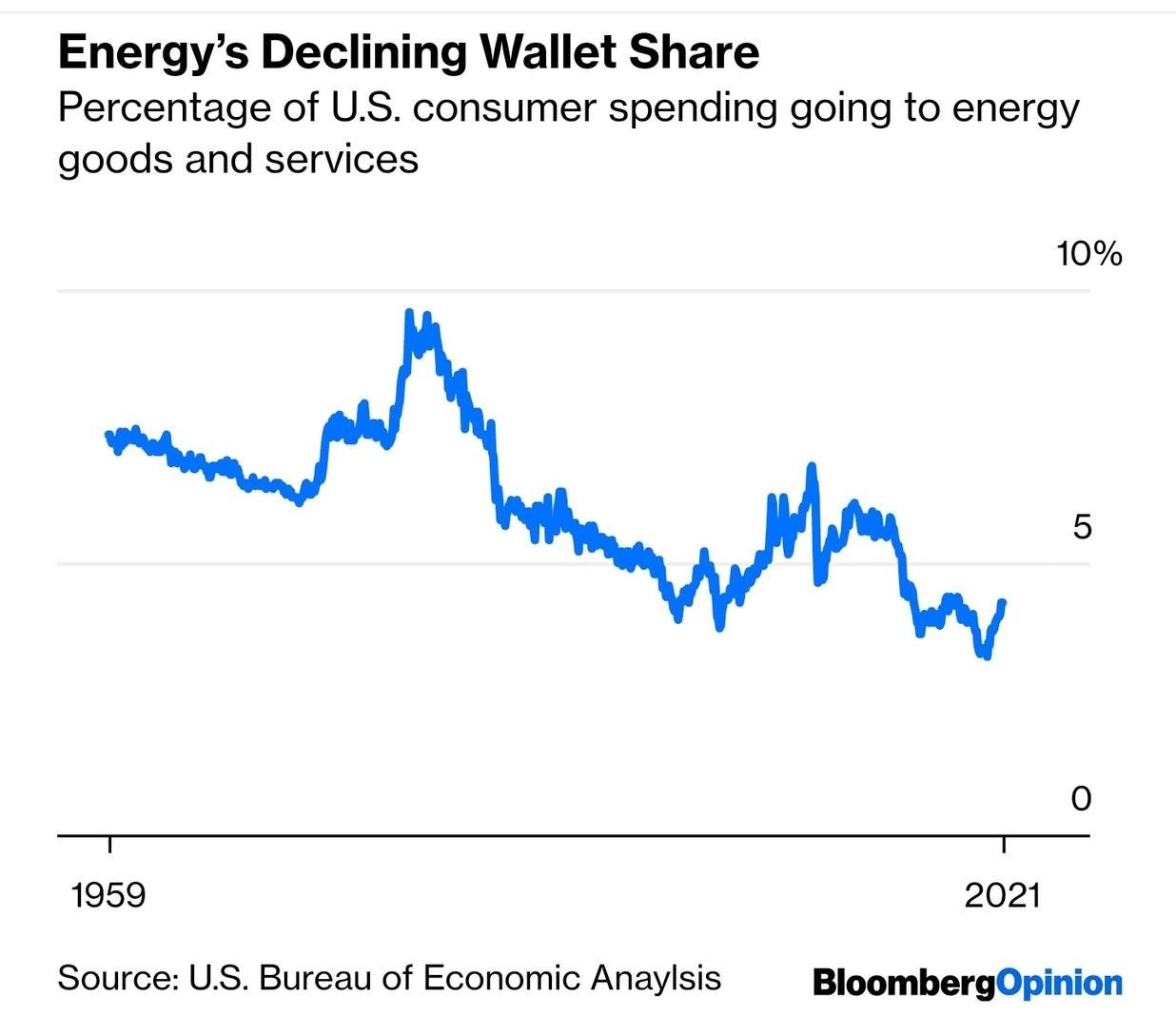

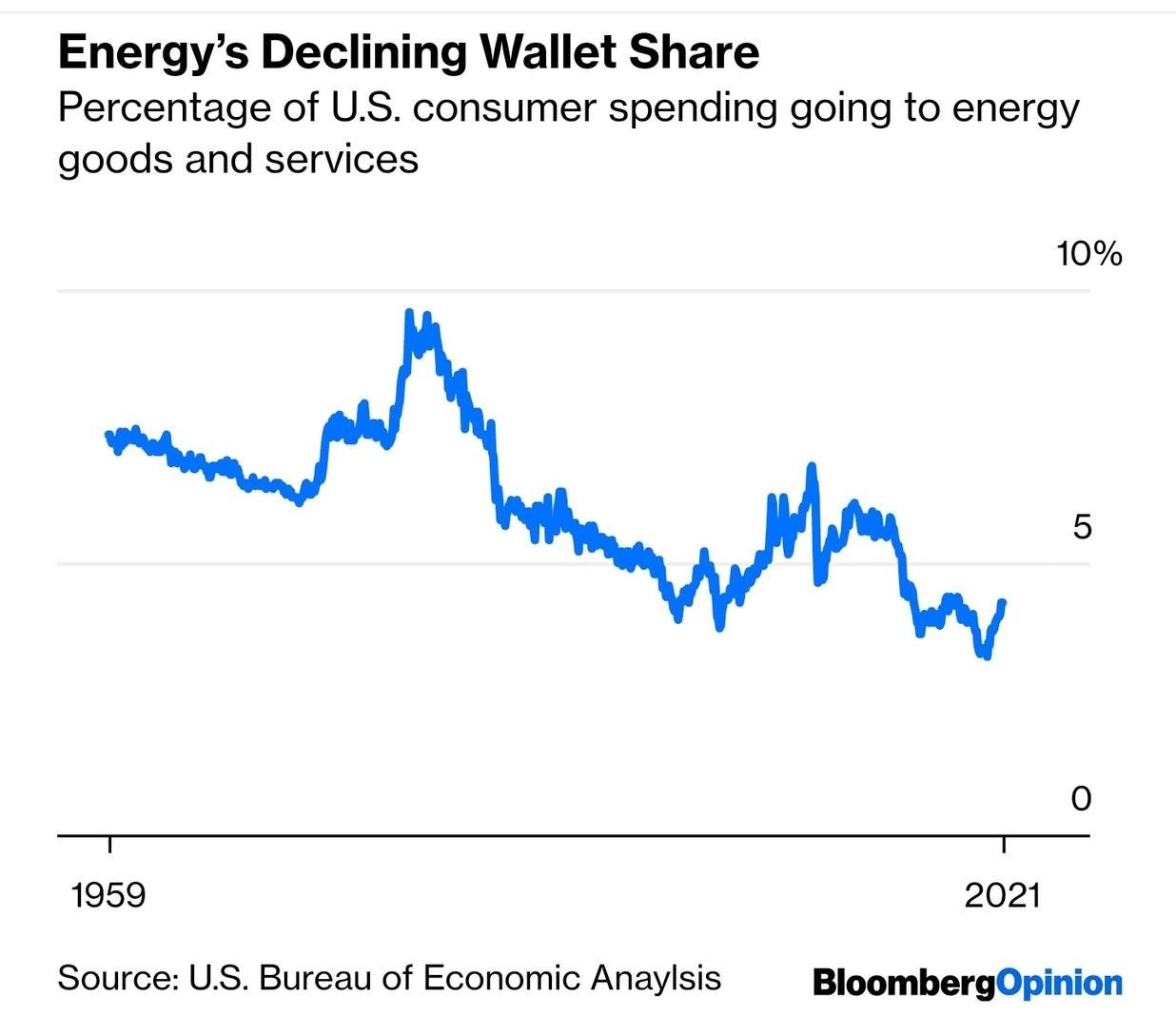

On the bright side, the U.S. economy is a major energy producer and far less reliant on oil than we used to be, so higher energy prices alone (within reason!) shouldn’t risk a major economic shock like they did in, say, the 1970s or 1980s:

Higher commodities prices aren’t always passed on to U.S. consumers (especially for food), but we should nevertheless expect to see food and energy prices rise and remain uncomfortably high in the coming weeks—precisely the opposite of what American shoppers and central banks, already grappling with inflation, need today.

Probably the biggest economic concern, however, isn’t what’s happening right now but what might happen next. What will happen, for example, to already stressed global supply chains with energy supplies and shipping routes disrupted, or if cyberattacks are unleashed? Will economic problems in more-exposed Europe spread to the United States, or will the armed conflict itself spread? (As AEI’s Michael Strain notes, the costs of the latter are potentially massive.) There are also open questions about the longer-term effects of the unprecedented financial sanctions—particularly those unleashed against Russia’s central bank and targeting the SWIFT bank messaging system—that the United States and so many other countries have now unleashed.

What will they unleash next? And, of course, how will Russia and Putin react? We just don’t know, and this extremely heightened uncertainty—as shown in numerous economic studies on the subject—is sure to weigh on U.S. and global economic activity (spending, investment, innovation, etc.) in the coming weeks and months.

The ‘Liberal Order’ and ‘Hayekian Sanctions’

On a brighter note, those epic multilateral sanctions and the global response more generally seem to ushering a shift in the pre-invasion conventional wisdom about the inevitable rise of nationalist illiberalism. All of a sudden, national populists in the United States and Europe (and heretofore Putin fanboys/girls) are distancing themselves from Russia, while—as AEI’s Kori Schake notes—the much maligned “liberal order” of the West appears to be ascendant:

Vladimir Putin has attempted to crush Ukraine’s independence and “Westernness” while also demonstrating NATO’s fecklessness and free countries’ unwillingness to shoulder economic burdens in defense of our values. He has achieved the opposite of each. Endeavoring to destroy the liberal international order, he has been the architect of its revitalization.

There has been a ton of ink spilled on the coordinated government actions from not just the United States, the U.K., and Europe, but also Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey, and even usually neutral Switzerland and frequent tax havens Cyprus and Monaco. Certain Chinese banks have also cut ties. Overall, the government response has been swift, broad, and—as detailed in this useful Alan Cole article—effective (so far). As such, it is a direct rebuke of the nationalist/populist trope, pushed by Putin himself, that the post-war liberal order—grounded in multilateral cooperation—has become impotent and obsolete.

It seems it just needed a little motivation.

Just as impressive, however, has been the non-governmental response—a private, bottom-up, spontaneous, and uncoordinated avalanche of “sanctions” against Russia and Russian interests around the world. As Schake explains:

Ukraine’s tenacity and creativity have ignited civil-society energy, corporate strength, and humanitarian assistance. The hacker group Anonymous has declared war on Russia, disrupting state TV and making public the defense ministry’s personnel rosters. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has promised to help keep Ukraine online. The chipmakers Intel and AMD have stopped sending supplies to Russia; BP is divesting from its stake in the Russian energy giant Rosneft; FedEx and UPS have suspended service to Russia. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is cutting all its investments in Russia. YouTube and Meta have demonetized Russian state media.* Belarusian hackers disrupted their country’s rail network to prevent their government from sending troops to support the Russian war. Polish citizens collected 100 tons of food for Ukraine in two days. Bars are pouring out Russian vodka. Iconic architecture in cities all over the free world is lit up with the colors of the Ukrainian flag to show solidarity. Sports teams are refusing to play Russia in international tournaments. The London Philharmonic opened its Saturday concert by playing the Ukrainian national anthem, and the Simpsons modeled Ukrainian flags. This is what free societies converging on an idea looks like. And the idea is this: Resist Putin’s evil.

Since that was written, there have been dozens more high profile moves by private parties to sever ties with Russian parties or otherwise support Ukraine—shipping companies, film studios, automakers, tech companies, oil traders, sports leagues, and on and on and on. It’s impossible to keep up with them all. (Reason’s Natalie Dowzicky is keeping a running list, and Eric Boehm adds more.) Here’s one of my personal favorites:

These spontaneous, diffuse, and asymmetric “sanctions” are pretty unprecedented, and some of them could go too far (let’s please not start acting like every Russian is a Putin stooge, ok?). But these non-violent actions do have some benefits, including over their state counterparts. They could, for example, be harder for the Russian government to respond to or explain away, and in many cases (e.g., divestments) they’re more serious because they can’t be reversed overnight. Indeed, Russia’s immediate response to the divestments—temporarily banning Western companies from exiting their Russian investments—is a boneheaded way to make things even worse in the long-run by discouraging future investment in the country.

I’d wager that most of these actions are, as Schake indicates, driven by a moral revulsion to what we’re seeing on our screens in almost-real-time—a testament to those oft-maligned smartphones and social media websites that, per the Financial Times, have utterly confounded the Russian propaganda machine: “Even some of Putin’s most ardent supporters appear concerned that Russia is struggling to wrest control of the narrative.” However, even if the private, “Hayekian” sanctions implemented by various multinationals are driven by pure self-interest (e.g., public relations), it’s a testament to Adam Smith’s age-old lesson as to how “selfishness” and the free market can be powerful forces for public good.

(Smith and Hayek in the same paragraph? LOL.)

Peace Through Commerce?

Similarly, we may be witnessing a revival of the longstanding notion that globalization promotes peace—whether the participants like it or not. As I wrote a couple years ago on the literature in this regard:

[A]rmed conflicts decrease as nations’ economic interdependence and trade openness increase, and a country should seek to encourage other countries’ global economic integration to discourage future attacks on that country. These national security benefits are driven by several factors: First, by making countries more commercially interdependent, trade encourages these nations to avoid war or other large‐scale armed conflicts (which could impose substantial economic losses). Second, trade and commercial bargaining are more cost‐effective than war as a means of resolving disputes with, or obtaining resources from, another country. Third, trade increases material prosperity (e.g., goods, services, investment, ideas) and promotes mutual tolerance and understanding. And fourth, free trade can limit the political power of domestic constituencies that may benefit from increased conflict.

Regardless of the reason, the outcome is clear: while global economic integration cannot eliminate armed conflicts, trade liberalizing policies make peace among nations more likely (and thus enhance national security) than the nationalist alternative.

Here, of course, Russia’s economic integration didn’t stop the Ukraine invasion (though Putin was actively trying to decouple from the West for the last few years). But could the massive, global response and the resulting economic destruction in the still-connected Russia (occurring in expected and unexpected ways) serve as a warning for other illiberal countries that also have extraterritorial ambitions? As Bloomberg’s Conor Sen put it:

The Wall Street Journal’s Nate Talpin concurs: “[B]y acting in concert, the owners of all the major reserve currencies have sent a very strong signal about the consequences of direct aggression against a neighbor by a major power while showing the limited advantages of diversification. … This week has been an unhappy wake-up call for Beijing.”

I wouldn’t go that far just yet—there’s still a lot of clock left in this game (unfortunately); China is a much bigger and different animal than Russia; and there’s a chance that these untested sanctions backfire in certain ways (e.g., by emboldening China’s SWIFT alternative, though these risks are probably oversold). But it’s impossible, I think, to deny that the last week—especially the broad and intense multilateral response to Russian aggression, public and private—has changed the calculus of both illiberal governments around the world and those in the West who champion “economic decoupling” from those same governments on national security grounds. Put another way, are we perhaps seeing, as Middlebury professor Gary Winslett just put it, the rise of “Pax Democratica”?

This Pax Democratica is different than the Pax Americana. Americans, somewhat haughtily to be honest, saw the Pax Americana as a thing we authored and that was a gift we bestowed on others, whether they wanted it or not. This is not that. This would a system in which, even if the United States remains the largest single player, every liberal democracy in the Pax Democratica understands that it is a multipolar global system, that it would self-consciously include non-Western democracies, that the United States would act with others’ interests in mind and not from a posture of ‘America First.’

Again, it’s too early to say, but…

What Else Should be Done?

Finally, a few quick words on U.S. policy moves to improve the short- and long-term situation here and abroad:

Fast-track permitting of U.S. oil and gas infrastructure. The United States can’t quickly ride to Europe’s gas rescue, and energy contracts are complicated things (especially for liquified natural gas). But the last week again shows why domestic regulation shouldn’t be an active impediment to the deployment of additional U.S. energy resources. According to the CEO of the American Exploration & Production Council, for example, there are now four pending applications at FERC to expand, relatively quickly, three already approved U.S. LNG export facilities and thus add about 5 billion cubic feet per day of additional U.S. export capacity (“roughly equivalent to the amount of gas that would flow through the Nord Stream 2 pipeline”). Proposed changes in FERC policy might also “mean a harder road for new pipelines to clear regulatory hurdles.” We really need to cut this stuff out.

Waive the Jones Act indefinitely. One of the reasons why the U.S. imports any Russian oil at all is because “[the Jones Act … has effectively limited the size of vessels that are allowed to transport goods between U.S. ports,” and “[i]t isn’t profitable for companies to ship oil from that region to the U.S. East and West Coasts by such small ships, so refiners along those coasts, lacking pipeline connections from the Permian and Cushing, mostly import it from overseas,” including from Russia. East Coast energy companies occasionally buy LNG from Russia because of the Jones Act too: “The United States has not produced an LNG carrier since the 1980s and U.S. shipbuilders have shown little inclination to reverse course especially now that they could never compete with carriers built elsewhere.” Even after protectionist amendments made waiving the Jones Act difficult (limited only to national defense), you’d think the current moment was sufficient reason to do so.

Eliminate “national security” and other tariffs on imports from Ukraine (and any other country in the region). It’s horrible (and telling!) that the United States has since 2018 imposed “national security” tariffs on Ukrainian steel (totaling around $570 million in 2019). While that past mistake can’t be remedied now, President Biden could at least lift the tariffs and approve any pending exclusion requests in case Ukraine’s commerce resumes. He should also do the same for any other countries in the area (including by lifting the new quotas on European steel). In the longer term, Biden and Congress should reinstate the “generalized system of preferences” program, which gave Ukraine and other developing countries limited duty-free access to the U.S. market but expired in 2020. (Sigh.)

In general, impoverishing allies, especially poor ones, is a really stupid idea; here, it’s borderline criminal.

Expand immigration for Ukrainians and Russians. Finally, I’d be remiss not to mention the role for immigration policy—for both humanitarian and strategic reasons. Granted, most of the heavy lifting will be in Europe due to sheer geography, and there have already been some positive signs in that regard (e.g., both Estonia and Moldova opening their doors wide open). But there are tens of thousands of Ukrainians already here, and there are some relatively simple moves—such as designating Ukraine for “temporary protected status” and Ukrainian students here “special student relief,” as some members of Congress just requested—that Biden could implement tomorrow to ensure their safety.

But more will need to be done. As our new Dispatch-er Klon Kitchen noted last week, for example, there could be millions of Ukrainians displaced in the coming days:

My Cato colleague Alex Nowrasteh laid out some things Biden could do quickly to help these people—and, as we discussed last year in the context of Afghan refugees, there are strong humanitarian and economic reasons to do so.

In terms of broader U.S. strategy, we could strengthen our economy and potentially weaken Putin’s regime by “offering a green card to any Russian with a technical degree who wishes to emigrate to the United States.” And we should do this for other authoritarian regimes, too, thus re-embracing the consistent and longstanding U.S. Cold War policy of using immigration to achieve strategic foreign policy goals. Sure, the usual suspects will complain, but this policy is precisely what a confident economic superpower engaged in a real and supposedly-existential global struggle would do.

I mean, are we in a “New Cold War” or not?

Charts of the Week

The Links

Sam Gregg on industrial policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship

“Remote Work Seen More Persistent Than Planners Expect”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.