Dear Capitolisters,

Yesterday, President Biden walked the picket line with striking United Auto Workers union members in a show of support for their demands to “Detroit Three” automakers Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis (formerly Chrysler). He is the first president ever to join a union strike, a testament to how unions are a big part of Biden’s political persona, his reelection strategy, and his economic policies, which emphasize bolstering unionized U.S. manufacturing operations through a range of strings-attached industrial subsidies—especially for the electric vehicles that the UAW and Detroit Three are trying to make. As a result, and given the political and economic stakes (and drama) involved, the UAW strike has received ample media coverage (including here at The Dispatch).

Less mentioned, however, is that the UAW’s demands and actions aren’t just costly; they might—given the economics and recent history—actually speed the demise of the companies at issue, and thus the UAW itself. If so, the president’s own policies must share some of the blame.

Recapping the UAW Demands

With the obvious disclaimer that negotiations are fluid and terms can and do change, the UAW has demanded not only a 40 percent wage increase, but also the restoration of traditional pensions, cost-of-living increases (so that wages automatically rise with inflation), reducing the work week from 40 to 32 hours, increasing retiree benefits, and even a provision ensuring “that workers at closed plants would be paid at the same rate to conduct community service.”

Put it all together, and it amounts to a substantial increase in the automakers’ expenses. According to their internal calculations (seen by Bloomberg), in fact, the UAW’s contract demands “would add more than $80 billion to each of the biggest US automakers’ labor costs” and would increase all-in hourly labor costs to at least $150 per hour—more than double the $64 an hour that the workers currently make.

That’s a massive increase, but the UAW’s leadership counters that it’s both deserved and possible: Detroit automakers have been making record profits over the last few years, they say, and workers put in a lot of hardship time during the pandemic. So, it’s time to pay up, and President Biden agrees.

Economic Reality Has Entered the Chat

The problem, however, is that these demands run headfirst into a wall of economic realities. Most obviously, a substantial increase in Detroit Three automakers’ all-in labor costs would put their U.S. facilities at an even bigger labor cost disadvantage vis-à-vis their overseas and domestic competitors than the one they already face. On the import side, the Wall Street Journal notes that autoworkers’ wages in Mexico and Japan are 18 percent and 80 percent of their U.S. counterparts, respectively. Compensation in Korea is lower too, and—of course—it’s much lower in China, which currently dominates the global EV market.

Labor costs aren’t everything, of course, but they do matter—especially, as the Wall Street Journal points out, in a global market with lots of competitors, one of which just happens to be a major U.S. geopolitical rival:

Raising labor costs by as much as the UAW wants would make it harder to close the gap with China, said Tu Le, an auto industry consultant with long experience in China. “If the contract is anywhere close to those numbers, then maybe at least at the below-$50,000 price point we’ll be driving a lot of Chinese cars,” he said.

Of course, the U.S. has tariffs on Chinese imports and is throwing gobs of subsidy cash at domestic EV manufacturers to lower their production costs or offset higher EV prices, but that plan also runs into problems. The biggest one is nonunion competition here in the United States. Those manufacturers would avoid tariffs and qualify for subsidies, and also already enjoy a substantial labor cost advantage over the Detroit Three. According to various reports, the $64 per hour labor costs at Ford, GM, and Stellantis are higher than the $55 per hour cost at Japanese, Korean, and European automakers’ nonunion U.S. plants—a labor cost gap of $900 million per year. Labor expenses at market leader (and also nonunion) Tesla Inc. are even lower ($45 to $50 per hour).

Furthermore, tariffs and subsidies (newsflash!) don’t actually make a company competitive in the long term, which is what these automakers really need to be, especially if they’re expected to challenge Chinese automakers outside of the United States (i.e., in places with more growth and more consumers):

Big wage increases will make it harder for the U.S. to build an electric-vehicle industry that can challenge China’s dominance, said Willy Shih, a management professor at Harvard Business School. “This puts the administration really in a fix,” Shih said. “You can take the side of labor and say OK, let’s raise everybody’s costs. I get that, but then what’s the long-term competitiveness of the domestic industry?”… Moreover, IRA subsidies by themselves won’t be enough to build a sustainably competitive EV industry, said Shih. “You cannot run that industry on subsidies for the next 50, 100 years,” he said. “At some point you have to be globally competitive.”

Even UAW supporters admit competitiveness is a big problem for the UAW/Biden plan—and one that’s far less an issue for services that are more localized or non-tradable (and thus face less competition from nonunion rivals). As former Obama auto bailout czar Steve Rattner recently lamented, a company like UPS can more easily pass on higher, Teamsters-negotiated labor costs to American consumers because freight services are inherently localized and the latter don’t really have many other options. In a tradable sector like automobiles, on the other hand, “[i]f you raise wages too much, then production will flow somewhere else,” either to Mexico or to non-unionized plants in the U.S.

Tariffs also raise the already high U.S. EV prices, which might be good for automakers and the UAW but will be decidedly bad for American consumers and the proliferation of the very EV technologies the federal government is trying to push. As Bloomberg recently reported, for example, there are a lot more EV options in China and Europe than there are in the United States, especially for small and midsize options “with price tags that won’t break the bank.” That limited variety comes from U.S. tariffs and regulations blocking imports and from U.S. automakers’ focus on more expensive SUVs and premium models (so they can pay for investments in electrification and remain profitable). Meeting the UAW’s demands would exacerbate this dynamic (emphasis mine):

If the carmakers concede to the union on higher pay, [Bloomberg’s Kevin] Tynan expects they will in turn negotiate for a smaller, more flexible workforce, which would lock in fewer car models, fewer cars and higher prices. “If I can sell less and make more, that’s the whole point,” he says. In short, Detroit is drifting further and further from the starter car, while factories in China are specializing in it. Just don’t expect the latter to solve for the former anytime soon.

Elsewhere, Stellantis’ chief Carlos Tavares has echoed much the same: They can’t profitably build a $25,000 EV and meet the UAW’s demands. “Part of the things we need to discuss with our union partners is how we make affordable EVs in the U.S. that the middle classes can buy and that they are sustainable because they are profitable, ” Tavares said. If high costs or tariffs block those types of cars from the U.S. market, the EV transition will be more difficult (at best).

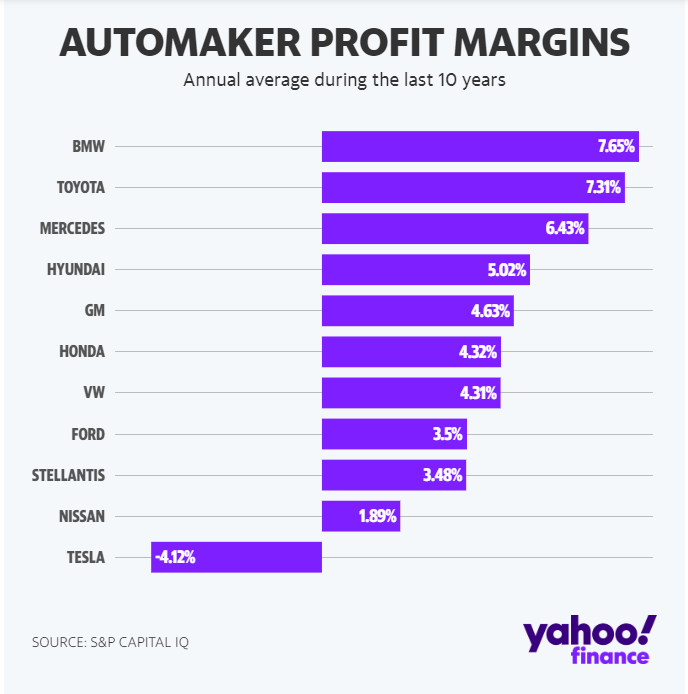

Speaking of Detroit Three profitability, that’s another big problem with the UAW’s plan. As Yahoo Finance’s Rick Newman explained, there was a short-term surge in automaker profits (thanks to stimulus-fueled, big-spending U.S. consumers and limited auto inventories), but that profitability is “meaningless” when you look at how these companies compare to other big automakers and Tesla, over both the short and long term:

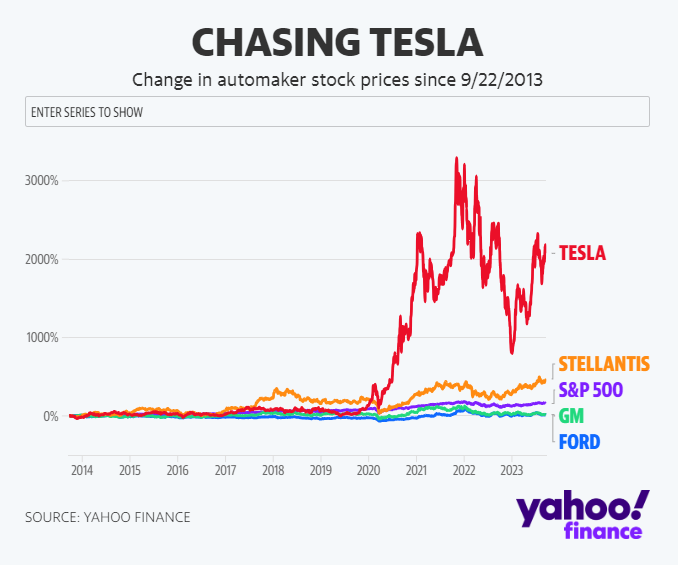

The Detroit automakers’ future profitability is also in doubt, in part because they’re spending so much to transition to EVs. As a result, investors are steeply discounting Ford’s and GM’s stocks, compared to its competitors and the S&P, while Stellantis’ stock reflects a lot of non-U.S. factors (because it’s a U.S.-European “mashup”):

Investors aren’t sanguine about the three automakers’ futures, as the market shifts from the gas-powered models that have dominated for a century to electrics that require completely different technology and massive amounts of up-front investment. Ford says it will lose several billion dollars on EVs this year. General Motors has struggled with technology problems and delayed EV rollouts. Stellantis says EV sales, mostly in Europe, have contributed to profitability, but it still needs deep cost cuts to stay profitable.

The current strikes certainly aren’t helping matters, either. According to an analysis from Michigan-based Anderson Economic Group, a 10-day strike would generate an industry-wide economic loss of more than $5 billion. The last time the UAW went on strike at GM, the 40-day standoff reportedly cost the automaker $3.6 billion in earnings, while workers lost around $1 billion in wages.

Newman thus concludes:

On paper, maybe the Detroit Three can afford to pay workers more and shareholders less. But nobody is asking their competitors to do that, and some of those competitors already enjoy advantages. The Detroit automakers aren’t the titans they used to be, and they’re not the titans the UAW seems to think they are, either.

Indeed.

Productivity gains (producing more with fewer workers) could be a way for Detroit automakers to offset higher labor costs and remain profitable, but here again the UAW plan clashes with economic reality. As Bloomberg’s Brooke Sutherland recently reported, North American carmakers have been investing heavily in industrial robots—installing 20,391 industrial robots last year, up 30 percent from 2021—to boost productivity and efficiency “amid steep competition in the electric-vehicle market and an escalating price war.” Companies like Ford are also investing heavily in “lean manufacturing” to continuously improve operations, eliminate waste, and compete with Tesla and others on price. “Such a wholesale rethinking of manufacturing processes,” she notes, “requires buy-in from every level of the workforce.”

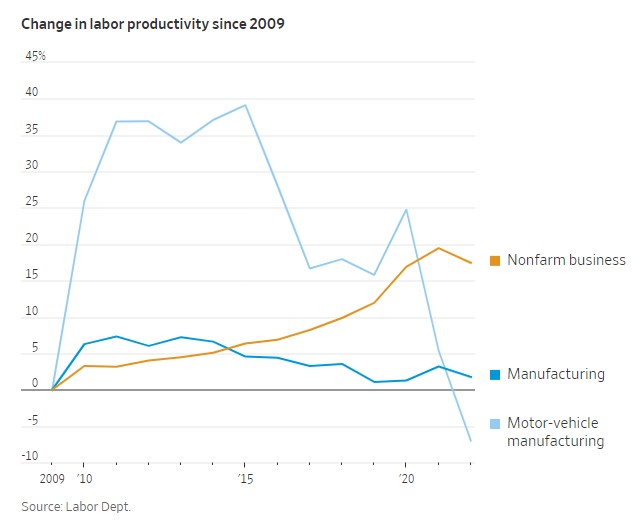

As the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip explained last week, however, the UAW doesn’t seem to be in the buying mood. In fact, most of its non-wage demands could actually lower per-worker output, even as productivity in the U.S. motor vehicle industry has been “especially bad” in recent years:

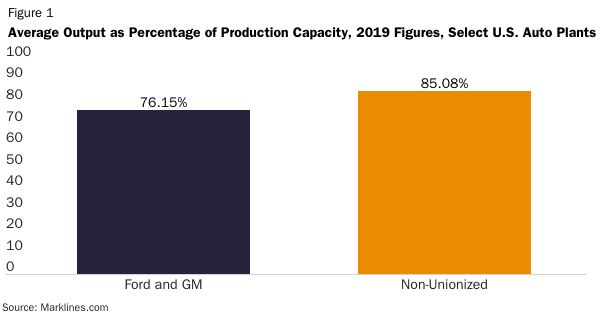

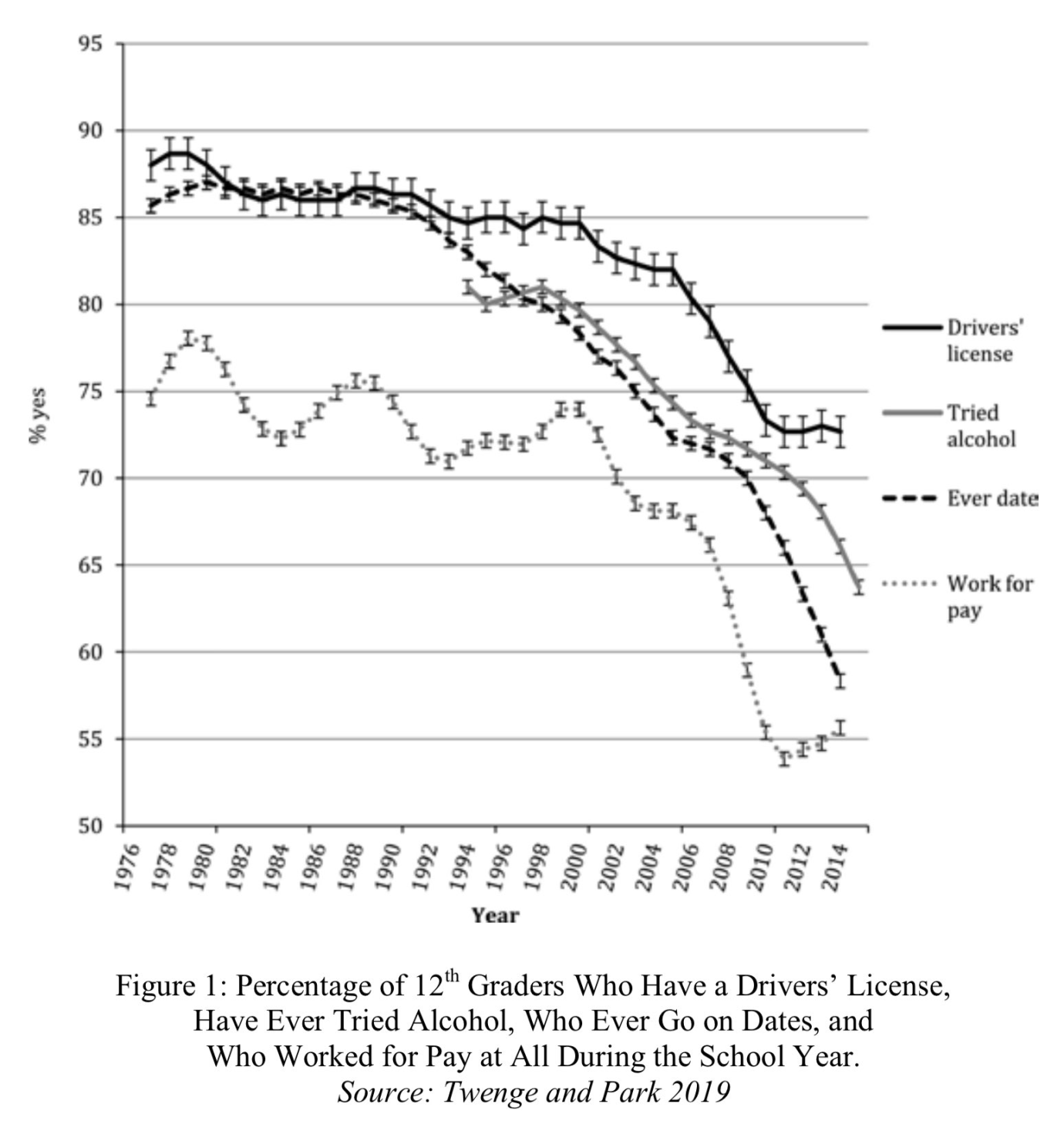

As Ip notes, many factors—not just labor—go into automakers’ overall productivity levels, but the UAW and Detroit Three have “performed badly” nevertheless: The companies have long been losing market share to vehicles—imported and domestic—made at non-UAW plants; their traditional vehicles rank poorly on consumer surveys of dependability and value; and they’re “far behind” Tesla on EVs. Indeed, as I noted a couple years ago when the Biden administration was pushing to limit EV subsidies to unionized plants in the United States, those plants were already less productive, less efficient, and less innovative than their nonunionized counterparts. In particular, nonunion factories and automakers 1) made about half of all vehicles produced domestically in 2019 yet accounted for less than half of U.S. automotive employment; 2) had higher average annual capacity utilization (actual production versus max production) levels than those of unionized plants (see Figure 1); and 3) have been quicker to invest and innovate in the EV space, in the United States and abroad.

Given these facts, the last thing Detroit automakers should be doing is signing on to a long-term contract that guarantees higher wages for fewer hours worked or—heaven forbid—actually paying UAW members not to work at all. It’d be economic suicide.

Ahh, Industrial Policy Doing Its Thing

In a normal market not being spurred by all these subsidies and regulatory mandates, an industry transition from traditional cars to EVs—maybe with hybrids bridging the gap between technology and consumer interest—might take longer, but it would also be less disruptive for almost everyone involved, especially unionized workers. EVs, as has been widely reported, have fewer parts than gas-powered vehicles and thus require fewer workers—as much as 30 to 40 percent fewer—and labor-saving technologies like robots will, as noted, be essential for traditional automakers’ long-term financial health. A slower EV transition might therefore have allowed these companies to let natural attrition (worker retirements, departures, etc.) handle more of the difficult task of shrinking their workforces and shifting to new, more productive technologies and factories.

The government, however, has no such patience, and is throwing hundreds of billions of dollars to accelerate the transition—whether the market is ready or not. This might be good for the environment, but the rush has put the UAW and Big Three on a collision course (pun), with both fighting to maintain future relevance in ways that openly and directly conflict with each other. Indeed, as the New York Times explains, the UAW is not simply fighting for more pay—they’re fighting to maintain relevance and power in an industry that’s using heavy federal subsidies to rapidly shift its workforce, technologies, and location:

Workers are trying to defend jobs as manufacturing shifts from internal combustion engines [ICE] to batteries. Because they have fewer parts, electric cars can be made with fewer workers than gasoline vehicles. A favorable outcome for the U.A.W. would also give the union a strong calling card if, as some expect, it then tries to organize employees at Tesla and other nonunion carmakers like Hyundai, which is planning to manufacture electric vehicles at a massive new factory in Georgia.

“The transition to E.V.s is dominating every bit of this discussion,” said John Casesa, senior managing director at the investment firm Guggenheim Securities, who previously headed strategy at Ford Motor. “It’s unspoken,” Mr. Casesa added. “But really, it’s all about positioning the union to have a central role in the new electric industry.”

As the NYT and many others have pointed out, billions in automotive investment is being driven, at least in part, by “pressure from government officials” (i.e., EV/battery subsidies and regulatory restrictions on ICE cars). But traditional automakers are currently losing money on the transition—“Ford said in July that its electric vehicle business would lose $4.5 billion this year”—while Tesla, which has lower costs, a smaller workforce, and no ICE transition to deal with, simply isn’t. As already noted, other rivals have lower costs too, which is a big reason why all automakers are taking their subsidies and setting up shop outside of union strongholds.

Meanwhile, American consumers remain hesitant about fully embracing EVs, thanks to “range anxiety” and a lack of adequate charging infrastructure—something Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm hilariously discovered herself during a recent promotional tour. Domestic inventories are swelling, and—as discussed—profitability is under pressure. Thus, Axios reported last month, “The EV transition will likely be longer and bumpier than many experts predicted—which explains why some automakers are hedging their bets, cutting prices and recalibrating their strategies.” In fact, just this week these issues—along with politics and (maybe) the UAW negotiations—pushed Ford to mothball a massive new battery plant in Michigan.

So, thanks to a fast—maybe too fast—subsidy-and-mandate-fueled EV rollout timeline, you have nervous car companies plowing cash into a not-quite-ready EV market and facing off against a nervous unionized workforce (and leadership) that wants to maintain, if not expand, a shrinking slice of the pie. It’s a recipe for a major conflict with no winners, and that appears to be what’s in the baking (heh). Adding insult to injury, the mess also appears to have made the Biden administration nervous about 2024: According to CNN, they’re providing as much as $15 billion in additional subsidies for automakers to convert old plants into “advanced vehicle” facilities—subsidies that the UAW had a hand in crafting and which were reportedly intended by the White House to win the union’s 2024 endorsement.

Gross cronyism aside, none of this is smart and good for the U.S. industry’s long-term competitiveness.

Forgetting History

How this all works out is anyone’s guess, but it sure sounds familiar, and not in a good way. For starters, costly, inflexible labor contracts—weighed down by especially generous benefits, pensions, and other things negotiated during boom years—were one of the main things that doomed Detroit automakers (and necessitated a government bailout) during the Great Recession:

According to GM’s 2008 tax filing, its operating costs in 2007 were $179 billion, of which $53 billion were fixed costs. Included in those fixed costs are “manufacturing labor, pension and other post retirement employee benefits (OPEB) costs, engineering expenses and marketing related costs.” The bulk of those costs is the product of labor‐management negotiations.

Those perks were trimmed during the bailout negotiations, but now the UAW wants much of this stuff back:

But requests to get paid to work 40 hours while only clocking in for 32 and calls for an essential revival of the “jobs bank” employment guarantee program that came in for particular scrutiny at the automakers during the financial crisis are unlikely to garner much support from the broader public in the event of a strike — particularly as the dollar impact starts to add up.

This also wouldn’t be the first time that union demands and conflicts disproportionately harmed the Rust Belt over the long term—a conclusion confirmed in a new paper from economists Simeon Alder, David Lagakos, and Lee Ohanian.

They first summarize previous “microeconomic” (firm- and industry-level) studies showing that “conflicted labor relations significantly depressed Rust Belt competitiveness and productivity,” and citing “strikes—and the threat of strikes—as important channels depressing Rust Belt productivity.” Then, they go further and conduct a novel examination of how labor conflict in the Rust Belt is connected to the region’s share of U.S. economic activity. They find that 20th century U.S. labor market conflicts (strikes, lockouts, etc.) occurred far more often at unionized manufacturing industries, including automotive, located in the industrial Midwest—about seven times as often as manufacturing in the rest of the country. This conflict, in turn, did generate a significant wage premium for the unionized workers involved (though it declined substantially from 1950 to 2000), controlling for education and experience. However, union conflicts also lead to less investment in the industries involved, lower productivity growth, and the long-term shrinking of Rust Belt industries and movement of workers moving out of the region.

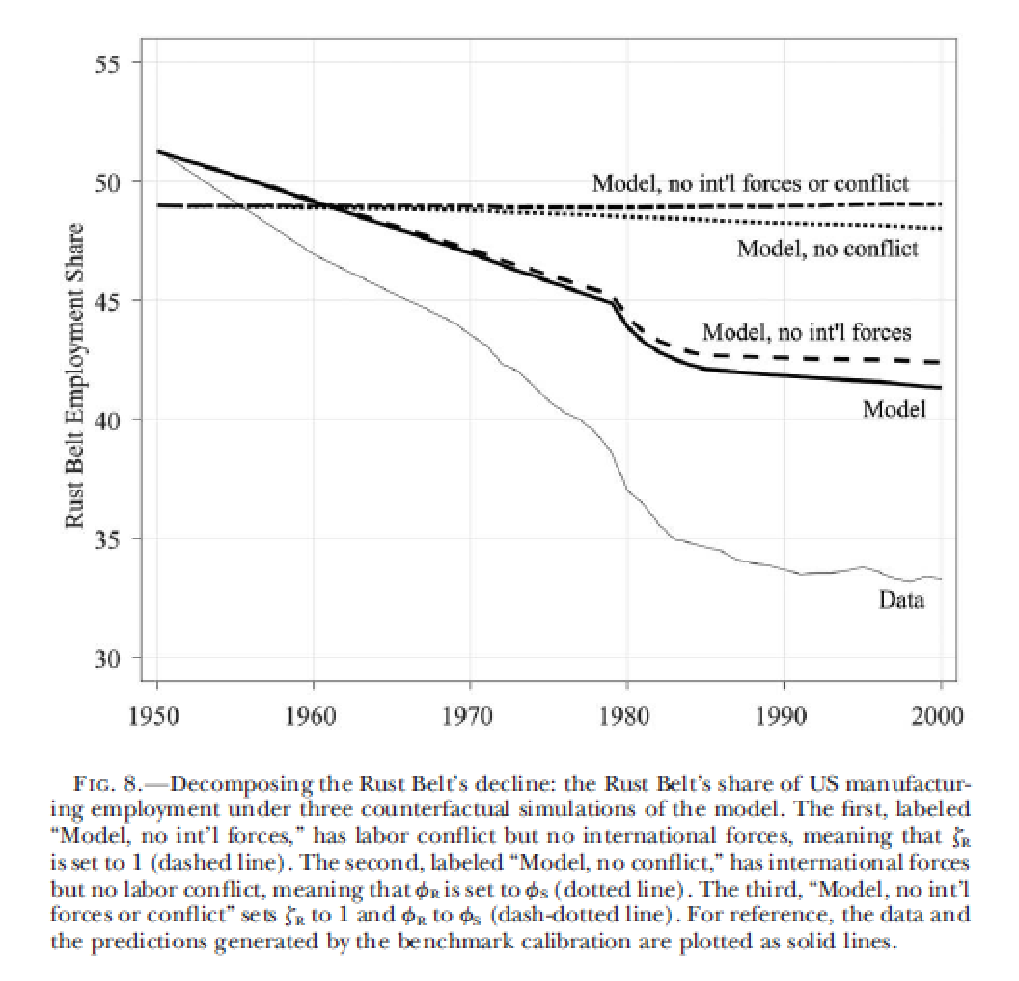

Overall, Alder, Lagakos, and Ohanian find that Rust Belt labor conflict, mainly before 1980, “accounts for half of the decline in the region’s share of manufacturing employment.” By contrast, the oft-scapegoated import competition “plays a smaller role, and its effects are concentrated after most of the region’s decline had already occurred,” as shown in the following chart:

The chart also shows that, following “legal and political shifts that substantially reduced union bargaining power in the 1980s, labor conflict declined, leading to higher rates of productivity growth and the region’s stabilization, albeit at a much lower level than before.” In short, union losses in the Rust Belt “were in large part self-inflicted.”

Will they happen again?

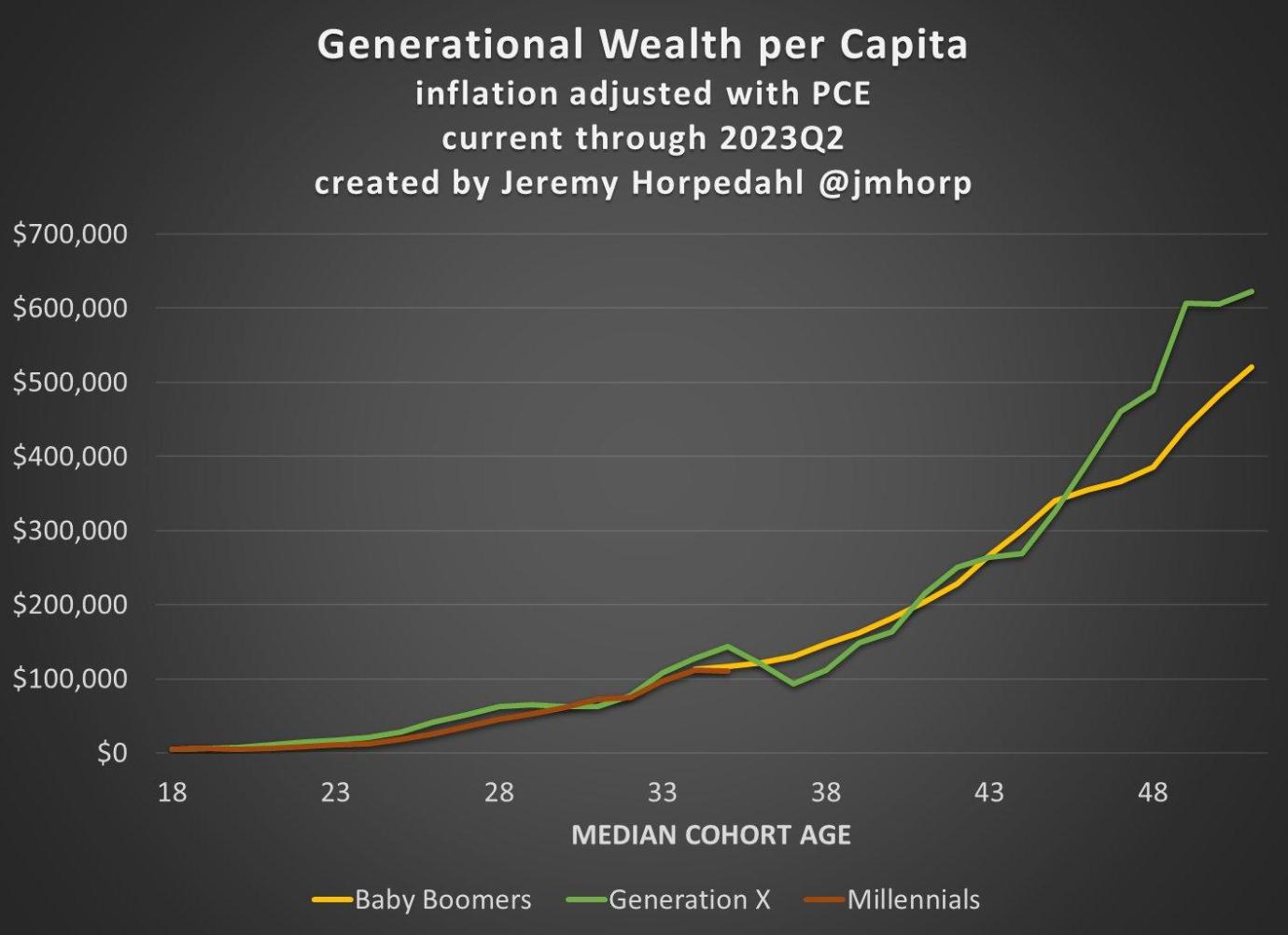

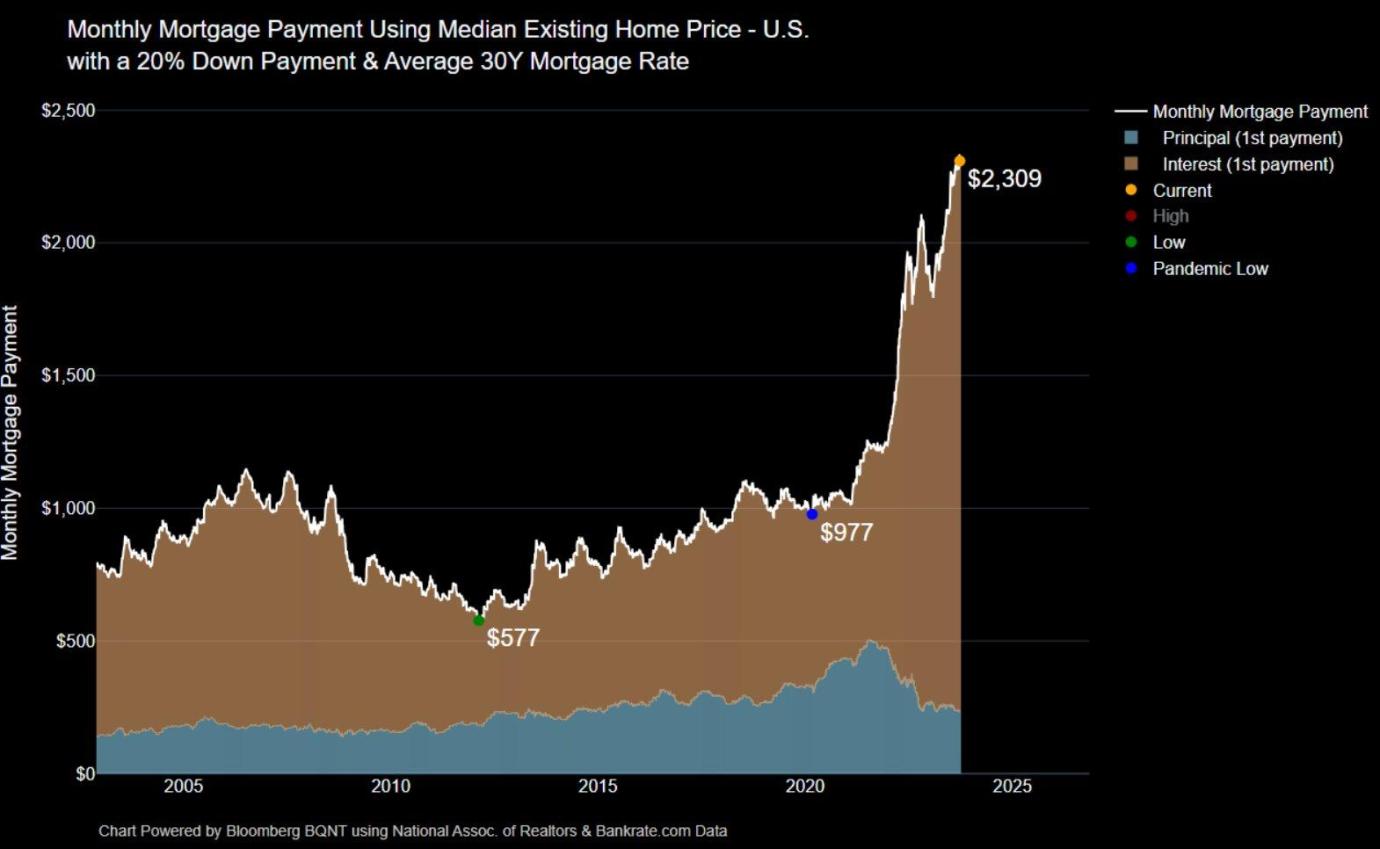

Chart of the Week

The Links

New Defending Globalization essays on the World Trade Organization, digital trade, and the “American System” of tariffs.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.