Four of the best—and often worst—words in the policy game are “I told you so.” They’re the best for obvious reasons: Seeing your advice and predictions proven right after having publicly gone out on a limb is always a great feeling—one certainly not limited to policy. Those words can sting, however, when bad things predictably happened because policymakers didn’t take your original advice.

Such is the case, alas, with Intel and U.S. industrial policy.

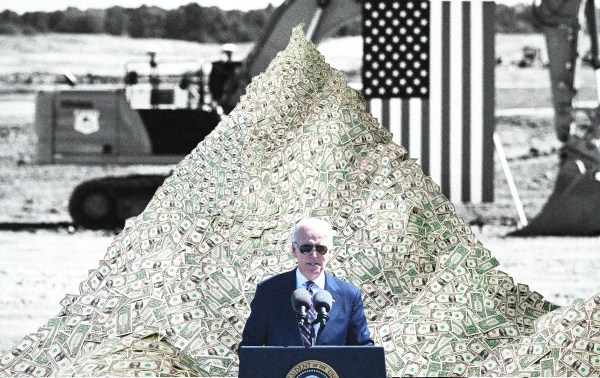

As you’ve surely heard by now, President Donald Trump announced last Friday that the U.S. government would be magically converting the billions in subsidies promised to Intel via the CHIPS Act and a separate defense-related program into a roughly 10 percent equity stake in the ailing U.S. chipmaker, thus making Uncle Sam its biggest shareholder. As you can imagine, I was not exactly a fan of this move and explained some of the reasons why in a short Washington Post piece published over the weekend. Since then, we’ve gotten more details about the deal, how it came together, and how markets are reacting—unfortunately all confirming, if not amplifying, my initial concerns.

And giving me a bittersweet opportunity to say those four little words.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Sigh, Where to Begin?

The most obvious and immediate problems with the Intel deal rest with the company itself, which—despite all those subsidies—has struggled even more since we dug into its many longstanding problems a year ago and briefly reviewed its current situation in July. As I wrote in the Post, there’s little reason to think this latest move will somehow reinvigorate the company:

With the U.S. government as its largest shareholder, Intel will face constant pressure to align corporate decisions with the goals of whatever political party is in power. Will Intel locate or continue facilities — such as its long-delayed “megafab” in Ohio — based on economic efficiency or government priorities? Will it hire and fire based on merit or political connections? Will research and development priorities reflect market demands or bureaucratic preferences? Will standard corporate finance decisions that are routinely (and mistakenly) pilloried in Washington, such as dividends or stock buybacks, suddenly become taboo?

The most common response to those concerns—including, quite depressingly, from some so-called “conservatives”—is that the government can’t possibly pressure Intel because its stake is passive: it must vote with the company’s board, has no board seats, etc. Yet, even at the time of the announcement, this claim looked silly. As I noted in the Post, for example, Intel’s board agreed to the deal only after Trump frog-marched its CEO, Lip-Bu Tan, into the Oval Office on bogus charges of Tan being compromised by China. The deal’s terms, meanwhile, showed that the government was already exerting real leverage over Intel before the ink was dry:

[The U.S.] purchased shares at $20.47 instead of Friday’s $24.80 closing price — a discount at current shareholders’ expense. Intel’s board green-lit the below-market transaction without shareholder approval, showing how management now prioritizes government interests over fiduciary duties. And the deal allows the government to purchase an additional 5 percent of the company at $20 per share if Intel sells part of its struggling foundry business, thus distorting government and management views of specific corporate restructuring decisions.

Since then, the Wall Street Journal’s behind-the-scenes tick-tock of the events leading up to the announcement confirmed that the 5 percent bump provision was forced on Intel to “dissuade the company from fully exiting the manufacturing segment.” The report also revealed that Intel’s “panicked” board of directors was effectively coerced into the deal because of Trump’s CEO threats, in a scene right out of The Sopranos: “In return for Trump’s support [for Intel’s CEO], the administration proposed taking an equity stake in the company.”

Nice company you have there …

This pressure, of course, came before the U.S. government had an actual stake in the company—and thus in its success (or failure). It’d be downright foolish to think the Trump administration’s leverage (and incentive/willingness to use it) won’t be even stronger now that Washington owns a big chunk of the company and Trump has put his own “businessman dealmaker” reputation on the line. No surprise, then, that Intel explained in a brand new SEC filing on the equity deal that the government’s stake “reduces the voting and other governance rights of stockholders and may limit potential future transactions that may be beneficial to stockholders.” It also says the government may vote “as it wishes” (and against the board) under certain express conditions, including if Intel ever tried to change or terminate “the Company’s or its subsidiaries’ relationship with the US Government.”

In other words, yes, Trump and the rest of the federal government will have influence and may even call some shots—at shareholders’ and/or Intel’s expense.

That incentive gets to the next clear problem that the equity stake raises: the potential to distort other U.S. companies and industries. As I wrote at the Post, for example, Intel’s competitors—not just chipmakers—could get less favorable treatment from the government, in terms of contracts, subsidies, tax or tariff relief, or regulatory approvals. Private investors might also shift toward Intel—and away from other, better semiconductor firms—not for market-based reasons but because “Uncle Sam now has a thumb on the scale.” With Intel’s long-suffering stock price having spiked 20 percent since news of the equity deal leaked in early August, these effects might already be taking root and reversing the market’s clear verdict about the company’s (and its competitors’) future:

Then there are the potential harms for Intel’s possible customers, who may suddenly look to buy from the company—not because it makes the best products but “to curry favor with or avoid being targeted by an administration that has a direct financial and political interest in Intel’s financial success.” This risk also appears to be materializing already: Minutes after I wrote my op-ed, we learned that Samsung was reportedly “exploring partnerships with American companies to ‘please’ the Trump administration and ensure that its regional operations aren’t affected by hefty tariffs.” And this “exploration” included “a deal with Intel [that] would allow the Korean giant to see an elevated status in the eyes of President Trump, mainly since Intel has become an important factor for the current US administration.”

Even outside of Intel’s orbit, I explained in the Post, corporate decision-making is bound to be distorted by the deal:

Will other companies that have received U.S. subsidies — trillions of dollars of which have been promised or paid since 2021 — alter their business practices to avoid or attract similar government intervention? … Will investors and entrepreneurs stay away from critical industries that might also see the U.S. government eager to get more involved? Will future presidents, Republican or Democrat, use this noncrisis precedent to carry out their own adventures into corporate ownership with their own economic and social priorities attached?

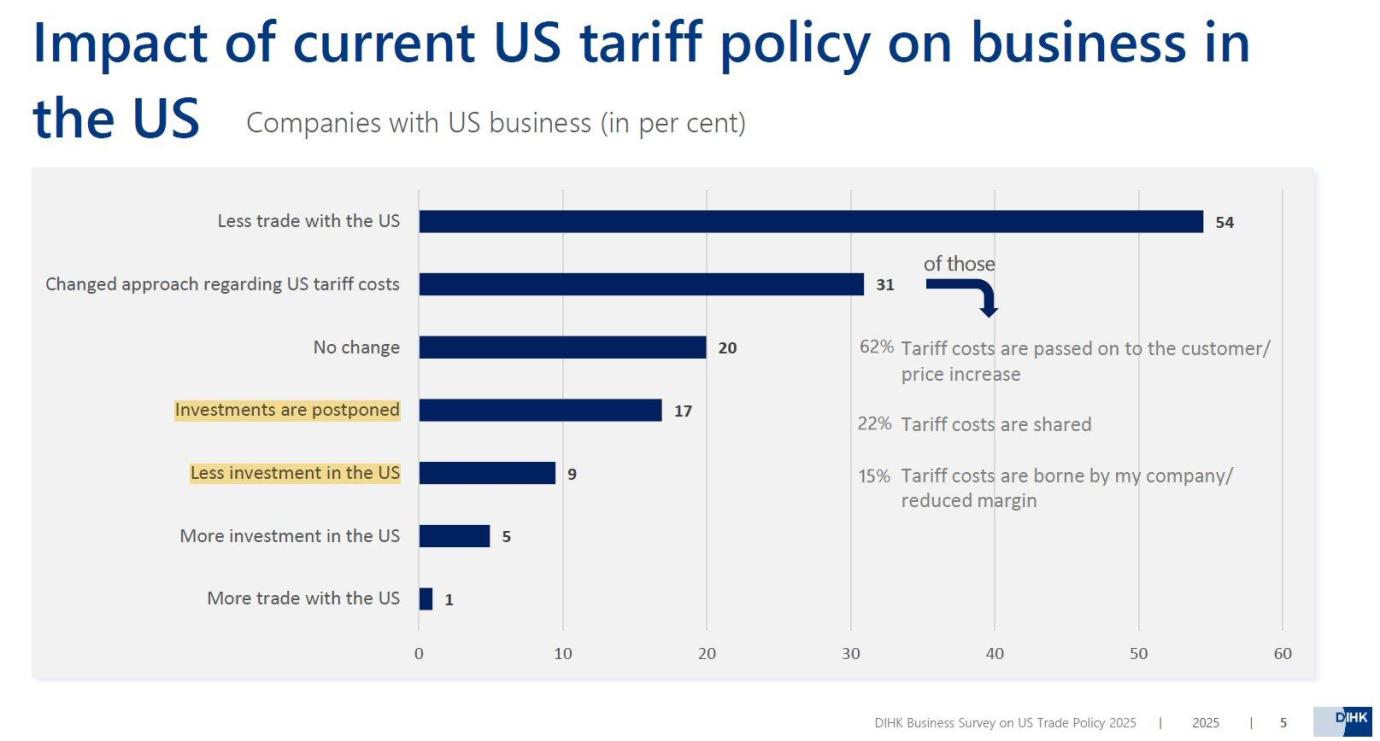

The Journal reported last week, in fact, that TSMC was already considering returning its CHIPS Act money because executives there didn’t want Trump to try to cajole them into an Intel-esque equity deal. Similar concerns are bound to proliferate now that both Trump and National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett bragged this week that they want to do more of these deals to reverse-engineer some sort of (legally and economically dubious!) sovereign wealth fund. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick followed with speculation about similar equity moves for defense firms like Lockheed Martin, Palantir, and Boeing. That kind of talk—along with the actual strong-arm moves for Intel, U.S. Steel, Nvidia, Apple, and other U.S.-based firms—will surely cause companies to think differently about how they do business in the U.S., or whether they do it at all.

Pandora’s Box, in other words, is now wide open.

And, as Tahra Hoops of the tech think tank Chamber of Progress smartly notes, these distortions don’t require any formal government action. Instead—

The danger here is institutionalizing “soft coercion.” It creates a shadow tax on non-Intel choices, companies must factor in political retaliation when deciding procurement. That’s a hidden subsidy for Intel, invisible on government books but real in cost to competitors and consumers.

And, in turn, to the U.S. economy and tech sector.

But, c’mon, this is Donald Trump we’re talking about here—the same guy who strong-armed Nippon Steel into granting him a “golden share” of U.S. Steel, who conditioned export licenses on getting a cut of Nvidia’s and AMD’s sales in China, and who has badgered countless private companies—in person, online, whatever—into following his orders or facing the full wrath of the government and his millions of devotees. It’s nothing short of a fantasy to think he’d just sit back and let Intel and other tech companies go about their business if Intel—and its very public stock price—continues to falter.

The more likely outcome in that case is more direct intervention by the government, whether it’s menacing threats and phone calls or even stuff like withholding tariff exemptions or export licenses until U.S.-based companies fall in line. As I noted in the Post, “Intel has expressly stated that its foundry business — the one in which the U.S. government is now extra invested — depends on finding customers, and now, Trump has a strong, and political, incentive to find them.” With Trump already bragging about Intel’s surging stock price, you’d have to be a fool to think he won’t meddle more in the months ahead, “ultimately weakening the United States’ long-standing tech dominance in global markets.”

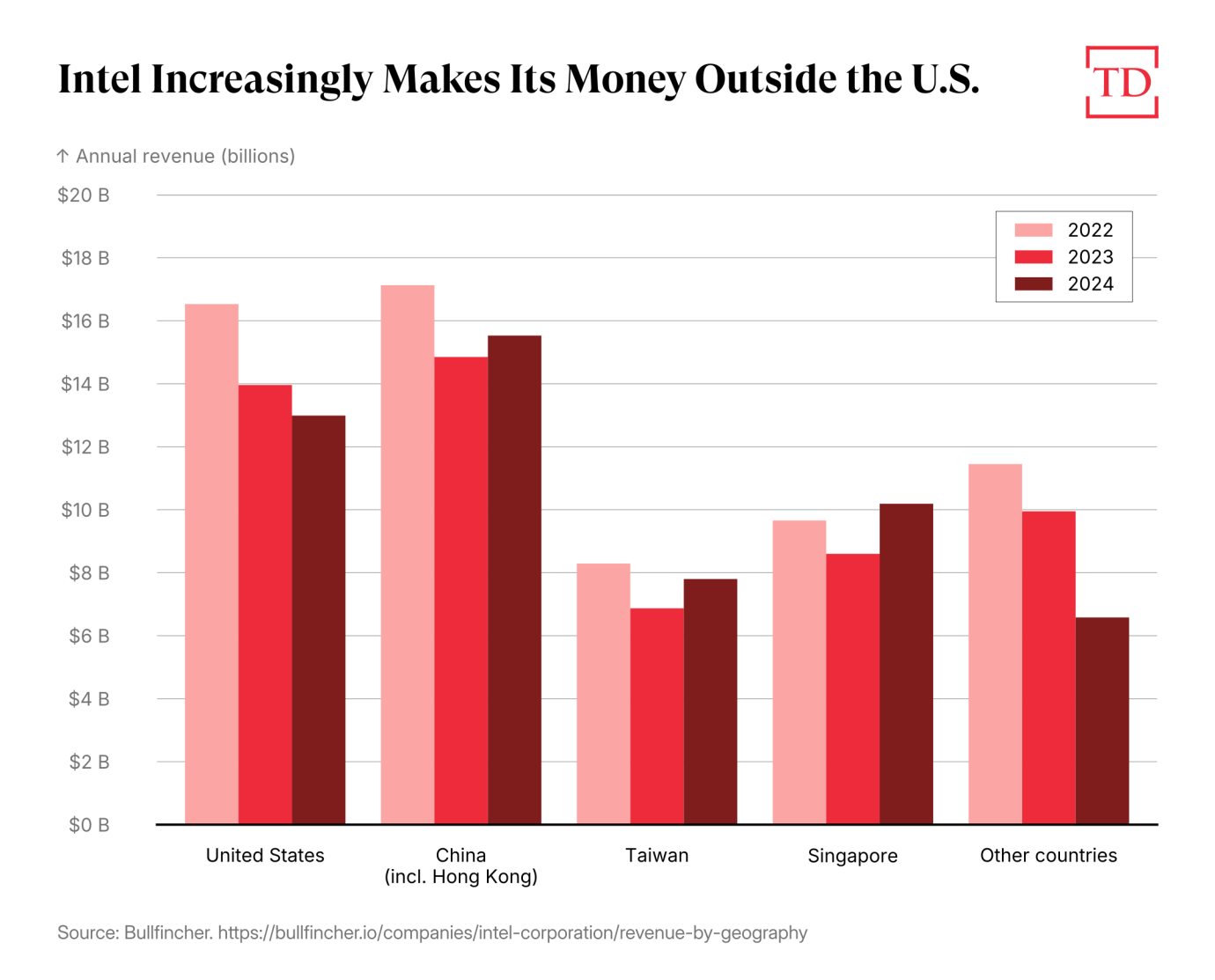

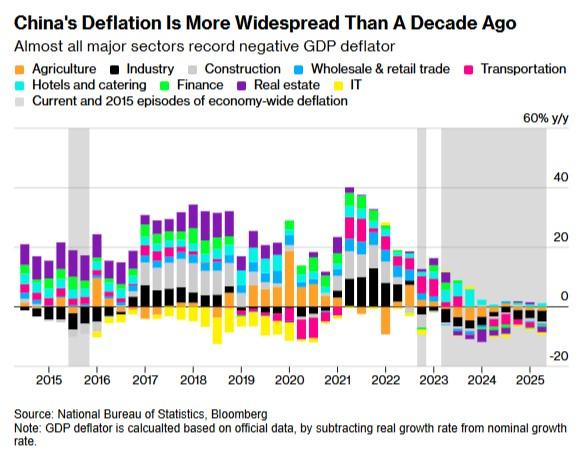

Finally, there are the trade and foreign policy risks that I didn’t cover in my Post piece. In particular, the Intel deal gives governments and companies abroad strong grounds to view the firm as an arm of the U.S. government rather than a private commercial entity, potentially limiting Intel’s revenues and global reach. Overseas customers for Intel’s foundry business, for example, might question whether their confidential intellectual property is safe from U.S. government prying. The Chinese government, meanwhile, could block Intel’s products, local business operations, or future M&A activity on national security grounds—a common CCP move. With a huge chunk of Intel’s profits coming from abroad, the equity deal risks hurting the firm’s bottom line—an “adverse reaction” its new SEC filing expressly mentions.

Governments might apply similar national security scrutiny to unaffiliated companies or goods that use Intel’s products (and not just chips). Or, as we discussed with U.S. Steel, they might start considering U.S. exports of these items to be “subsidized” indirectly by the U.S. government (e.g., because they contain Intel chips purchased at below-market prices), thereby justifying new trade restrictions (aka “countervailing duties”). That, too, would be bad for a globally successful U.S. tech sector.

These risks aren’t sure to materialize, but they’re now something U.S. companies using Intel’s products will need to consider (costing them more money on lawyers and lobbyists). And, ironically, governments that follow this approach would be mimicking Washington in doing so. The U.S. government has long treated state-invested enterprises as fundamentally different from, and more trade-distorting than, private companies and has codified this position in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement.

Overall, federal investment in Intel might paradoxically undermine the very economic and security objectives the equity deal purports to advance—and do so by Washington’s own standards. And, as is so often the case, there were many other ways to achieve the government’s economic and security objectives—market-based and government-backed—that don’t raise the risks that state investment raises.

Finally, a Quick Word About GM

One last defense of the Intel deal is that it’s not unprecedented because the U.S. government did something similar with General Motors (and Chrysler) in 2009—and, by the way, that turned out just fine. Yet this claim fails on multiple fronts. Yes, the auto bailouts were a brazen and legally dubious cramdown of ailing national champions that harmed existing shareholders and could’ve been handled in a more transparent and lawful—and less corrupt—way. But they also 1) occurred during a legitimate economic crisis; 2) were temporary; and 3) importantly involved a lot of government-demanded changes at the companies (new management, corporate restructuring, shedding assets, etc.). The Intel deal, of course, involves no such things and may, in fact, set the stage for more government entanglement in the months ahead.

Just as importantly, the auto bailouts were far from the economic success many partisans claim. As I summarized in a 2021 paper, in fact, they exhibited many of the seen and unseen costs about which U.S. industrial policy skeptics have long warned. Beyond the fact that the bailouts cost U.S. taxpayers 40 percent more than the Obama administration claimed ($14 billion once you adjust for interest), their hidden costs were even larger:

For instance, the $61 billion allocated to these corporations could have been spent on more productive initiatives, such as retraining autoworkers. The long-term competitiveness of GM and Chrysler was diminished because they were not reorganized via standard bankruptcy proceedings. Ford and other U.S.-based automakers who did not receive special treatment lost business, thus harming not only their finances but also American consumers and the economy, because these companies’ better products and business models were not rewarded. Moral hazards arose from encouraging the continuation of the companies’ and the United Auto Workers’ irresponsible practices. Bond holders and other investors suffered because they did not receive the fair value of their holdings, potentially short-circuiting U.S. bankruptcy law along the way. Then there are the political costs of protecting well-connected favorites (here, unions), and the cost of uncertainty about whether and when political actors would again decide to intervene in the market and legal system, citing the bailout as precedent.

That last cost has unfortunately materialized this week—and probably not for the last time.

Industrial Policy Chickens, Again

And that gets us back to the “I told you so” part of this column. As devoted Capitolism readers know well by now, none of this stuff—the ailing incumbent, the sunk cost-chasing, the “mission creep,” the cronyism, the unseen harms, and more—is the least bit surprising for anyone who knows the long and sordid history of U.S. industrial policy. As my colleague Ryan Bourne explained last week, in fact, the Intel deal is the next logical step: By boosting both the supply of and demand for government favoritism, the tariffs and subsidies embraced by both Trump and former President Joe Biden are the “gateway drug” to firm-specific cronyism:

Industrial policy and protectionism is itself a form of cronyism, but, at least in theory, it can be one grounded in clear rules and conditions, known in advance by all firms and limited in political discretion. In reality, what happens when you get a policy regime change that dishes out new privileges is a rush for favors or exemptions, breeding the bespoke, firm-level dealing that this President is only too willing to provide. As Tyler Cowen reminds us, Ludwig von Mises warned about this “interventionist ratchet.” A “middle-of-the-road” mixed economy isn’t a stable equilibrium, Mises thought, because one intervention begets the next and so we drift toward de facto state control or ownership.

…

Tariff walls and enormous subsidies furthered by both Trump and Biden cracked the door for cronyism and now we’re barging through. If we want to avoid state capitalism with American characteristics, we must recognize that the gateway drug was industrial policy itself.

Giving any president the power to pick winners and losers in the market is an open invitation to firm-specific cronyism like we’ve seen repeatedly this year. Sometimes, in fact, the government issues an actual open invitation, as it did recently with the massive expansion in U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs that also happened last week.

Yes, we “fundamentalists” warned of this exact thing. Now, unfortunately, we get to say “I told you so.”

Capitolism will be off next week.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.