One of Capitolism’s frequent themes/laments is how President Donald Trump’s policies, especially but not only tariffs, have caused many Republicans to drift from their free market roots toward a more populist, interventionist (borderline Peronist) view of federal economic policy. Yet Trump’s rapid, unilateral imposition of new taxes on a wide range of imported goods also appears to have caused another metamorphosis: Many Democrats are suddenly sounding like libertarians. Once ardent defenders of corporate taxes, regulation, redistribution, and activist government, prominent people aligned with the Democratic Party—not just economists and Abundance wonks but politicians, staff, and pundits—are now hitting Trump’s tariffs with arguments that would feel right at home at a Cato Institute event or in the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal and which contradict longstanding Democratic positions on non-trade issues in fundamental ways.

On at least four issues, Trump’s tariffs have handed the American left a lesson in how bad economics begets bad outcomes—and how classical-liberal critiques of interventionist policies, long dismissed or demonized by populist Democrats, actually have merit.

And to that I say, welcome to the party, pals.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Corporations Don’t Pay Taxes. People Do.

In pushing for higher taxes on corporations and other American businesses, prominent Democrats have long portrayed the levies as being paid by the companies themselves. When former President Joe Biden proposed in 2024 to raise the corporate income tax rate from 21 to 28 percent, he repeatedly said the move would make “big corporations pay their fair share” and bashed the recent rate reduction as a “massive tax giveaway” to those same companies. Such views are neither new nor isolated to Biden. In 2019, for example, Sen. Bernie Sanders lamented that “Amazon, Netflix and dozens of major corporations, as a result of Trump’s tax bill, pay nothing in federal taxes,” while his populist Democratic colleague Sen. Elizabeth Warren campaigned on a real corporate profits tax specifically to ensure large companies “pay their fair share.”

Unmentioned in all this populist rhetoric is the fact that—as Capitolism and many others have repeatedly explained—companies don’t really pay taxes at all. Sure, they fire off virtual checks to the Treasury, but studies show that the actual burden of corporate taxation (aka the “incidence”) typically falls on some combination of shareholders, workers, and consumers. The literature adds that higher corporate taxes tend to stunt investment and growth (while the recent corporate tax cuts did the opposite), and that onerous new business taxes are typically associated with clever corporate moves to avoid them. Yet when free marketers cited this research to argue that corporate tax hikes would inevitably lead to higher prices, lower wages, and less domestic investment, progressives routinely dismissed them (us) as apologists for the dreaded “big business.”

Then came the 2025 tariff shock, and suddenly many of these same Democrats are dissecting tax incidence like they’re prepping for an Econ 101 exam.

Most obviously, Democrats have been vocal about American companies—which in most cases are the ones technically “paying” tariffs when an item is imported—passing on those new costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. On the Senate floor in April, for example, Warren explained that tariffs are “a tax on companies when they bring something from overseas to sell to use”—a tax that CEOs “are already lining up to pass along … to American families.” As a result, she predicted, Americans will “pay more for shoes or washer machines or anything else you buy.” Progressive Rep. Ro Khanna of California said much the same to CBS News, suggesting that Trump’s tariffs would make the price of an iPhone “go up to $1,700 or $2,000” when Apple passed on its new tax costs to American shoppers. Rep. Suzan Delbene of Washington, the chair of House Democrats’ campaign arm, put it bluntly in May: “Tariffs are a tax on imported goods paid by American businesses and often passed along to American consumers.” And their colleague Rep. Jamie Raskin even vowed to introduce the “Truth in Tariffs Act,” which would “requir[e] retailers to display product cost increases to customers caused by President Donald Trump’s tariff policies.” The list goes on and on.

Democrats have also complained—again, correctly!—that American companies unable to pass on higher tariff costs will reduce other spending to offset the new tax burden. Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, for example, warned that Trump’s tariffs would crimp corporate investment and noted several consumer-facing businesses in her state that might shut down entirely because of the higher costs. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer echoed these concerns in an April speech, highlighting a Long Island apparel company that may need to delay its expansion and hiring plans because tariffs increased the firm’s costs by 30 percent. He added, “This is now the story of so many businesses across New York and the nation, and it is a needless harbinger of what might come if the President’s tariff war wages on.” Schumer also co-signed an April letter from several Democratic senators to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick explaining that, thanks to the tariffs, “[b]usiness owners are forced to decide between absorbing the costs while risking staff layoffs and potential closure, or passing the increased costs along to their customers with whom they have built a relationship and who are already facing high prices due to inflation.”

Just like any other corporate tax.

These statements aren’t, of course, revelatory: As we’ve repeatedly discussed, studies show that a substantial portion of Trump-era tariffs technically paid by American corporations were passed on to American consumers in the form of higher prices (e.g., for washing machines or solar panels), or that they depressed hiring and investment in U.S. firms that use goods hit by the tariffs (e.g., steel and aluminum). Yet it’s still somewhat novel to hear Democrats acknowledge this tax incidence—at least when it comes to this kind of corporate tax.

Regulations Often Hurt Small Businesses More Than Big Ones

Libertarians have long noted that complicated taxes and regulations tend to entrench big players and squeeze out small ones because the former has far more resources—personnel, capital, locations, etc.—to comply with new rules and adjust as needed. Democrats, on the other hand, have traditionally seen regulation as a means of curbing corporate power and have viewed deregulation as a tool of powerful corporate interests. While paying lip service to claims that new red tape disproportionately hurts small businesses, moreover, they’ve definitely not prioritized this concern in their policymaking:

Democrats’ rhetoric has been similarly lopsided. Raskin in 2023, for example, credited regulation with improving almost every aspect of our lives—our air, food, water, workplaces, travel, banking, toys, and more—while also praising the Biden-Harris administration for using the administrative state to “ensure that corporate interests must act in the public good.” He also denounced “the corporate-dominated Republican Party” for opposing such policies and previously using deregulation to help “corporate CEO’s and industry lobbyists.” Years earlier, Warren denied community banks were struggling under Dodd-Frank financial regulation and suggested that “regulatory relief bills” supposedly helping small businesses were really being “pushed by ABA lobbyists for the big banks.” The New York Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin summarized the conventional wisdom well in 2021: “Business is aligned with Republicans when it comes to taxes and regulations because … well, profit.”

When it comes to tariffs, however, progressive Democrats are suddenly singing a different tune, emphasizing that new trade regulations and related paperwork disproportionately advantage larger businesses over smaller ones. In an April letter to several Trump administration Cabinet members, for example, Sen. Ed Markey explained, “The Trump Tariffs have put small businesses in an untenable situation that threatens their survival,” while “[b]ig businesses have tremendous advantages over their smaller competitors due to their enormous scale and deep capital reserves.” He therefore asked that the administration exempt small businesses from the tariffs entirely. Around the same time, 68 Democratic representatives sent a letter to a broader set of Trump appointees, noting that small businesses “operate on thinner margins and do not have the sophisticated supply chain management staff that larger firms do, putting them at a competitive disadvantage” and that they “also lack leverage in negotiating more favorable terms when they attempt to shift supply chains.”

These Democrats are again correct. As we’ve repeatedly discussed, modern U.S. tariffs—and especially Trump’s 2025 tariffs—are always accompanied by new bureaucracy, and both experience with previous Trump tariffs and recent news reports show that smaller American companies are being overwhelmed by new tariff-related regulatory burdens—customs paperwork, tariff classification codes, exemptions, rules of origin, and more. Larger firms, by contrast, have more supplier options, more capital, and even employ former customs officials to navigate the bureaucracy and streamline shipments. They’re not just coping with these new burdens but actively bragging to journalists and shareholders about their new competitive advantage:

In the 2020 election, Democrats seized on Trump’s first-term deregulation efforts to claim he was only looking out for “big business.” Five years later, many of them seem to better grasp that regulation—whether from tariffs or any other law—doesn’t often work that way.

Big Government Breeds Cronyism and Corruption

When government systems become too onerous and complex, those with the most resources are more easily able to not just accommodate but directly exploit (and profit from) them. This dynamic is right out of the public choice theory textbook—but it’s not something Democrats typically address when introducing new and complicated regulations, subsidies, or tax schemes. In fact, populist Democrats have defended past expansions of the federal bureaucracy, such as Dodd-Frank in 2010, as a necessary safeguard against cronyism, not something that might fuel it. And, once again, they’ve long claimed that deregulation does much the opposite.

Trump’s 2025 tariff regime has again changed their script. That Markey letter, for example, complained that the Trump administration has used tariff policy to “shower” big corporations with special treatment that they won because they can afford it:

Just like small businesses, companies such as Apple and Google knew that these tariffs would be catastrophic for their bottom line. But unlike small businesses, which can’t spend enormous sums on lobbyists in Washington, these multibillion-dollar companies were able to obtain an eleventh-hour carve out.

In another recent congressional letter, Warren and her fellow Senate Democrats noted that “Trump’s use of tariffs during his first term as president showed his willingness to wield import taxes as a tool for him to reward his political friends and punish his foes.” They also worried that “the administration is once again turning its tariffs policy into an underground market of exemptions in exchange for financial and political favors,” and that Trump’s tariffs “are inviting corruption not only through quid-pro-quo arrangements but also through officials’ personal investments” that could be boosted by frequently changing U.S. trade policy. Other recent statements echo these concerns, which former Democratic Treasury Secretary Larry Summers summed up well:

When you start giving an exemption here and an exemption there on tariffs, it’s introducing all kinds of corruption into the system. It’s introducing what economists call rent seeking, where it’s hugely advantageous for people to be friends of the first family and hugely advantageous for people to hire a lobbyists. So, the big boom that’s being created with tariffs is in a crony capitalism.

Once again, Democrats have good reason to worry in this regard. History is replete with examples of protectionist policies—tariffs, baby formula regulations, Buy American rules, the Jones Act, and so on—being influenced, if not entirely captured, by big corporate insiders. New research further shows that “lobbying for tariff reductions by large firms was hugely more effective than for small firms” during the first Trump trade war with China. And a recent Reason analysis finds that tariff-related lobbying was 277 percent higher in the first quarter of 2025 than in the same period last year.

Yet it’s still somewhat shocking (albeit welcome!) to see the Party of Bureaucracy quietly acknowledge the favoritism baked into it.

‘Trickle Down’ Economics Might Actually Have a Point

Finally, Democrats have long derided the idea that reducing taxes or other government burdens on the wealthiest Americans and biggest corporations might also help lower-income workers and the U.S. economy more broadly. President Biden routinely dismissed the 2017 GOP tax cuts, for example, as a failed example of “trickle-down economics,” pushing instead for “middle out” policies (whatever that means). Warren has repeatedly done the same, going so far in 2015 as to savage the theory and take “a swipe at President Ronald Reagan” for policies that helped “Wall Street” and “the wealthy” but “devastated U.S. workers”—a common trope among populist Democrats for decades now.

There are, of course, legitimate questions over the effects of certain tax cuts and whether Republicans have ever actually embraced “trickle-down economics” at all. Yet when tariffs crippled U.S. capital markets in the spring of 2025 and wealthier Americans started pulling back on spending, Democrats suddenly started sounding a lot more like Art Laffer than Robert Reich. Warren, for example, noted that tariff “chaos” would hurt the economy because, “Investors will not invest in the United States when Donald Trump is playing red light, green light with tariffs.” Jared Bernstein, former Biden adviser and then-chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, worried that Trump’s tariffs had “evaporated” around “$6 trillion of [stock market] wealth” in just a few days, with attendant harms for Main Street. Sen. Brian Schatz echoed those concerns on the Senate floor, while Rep. Marcy Kaptur explained that the stock market declines “are not just numbers, they represent people losing wealth they worked for, evaporating retirement savings, businesses losing capital, cars not being sold, rising unemployment that has started in industrial and agricultural America.”

Even the commies over at Jacobin—Jacobin!—worried that, because America’s wealthiest households drive so much investment and consumption in the United States, Trump’s tariffs and the related stock market selloff would disproportionately harm their working class comrades:

With the country’s fortunes tied to tech barons and high spenders in the upper classes, a contraction in the stock market and a pullback on consumer spending by the asset-owning class would be catastrophic for the bottom 80 percent — who would be stuck holding the bag.

The author laments, of course, that The Rich own so much wealth in the first place, but his concerns are nevertheless right out of the “trickle-down” playbook.

And, hey, good for them. As we’ve discussed, populists are wrong when they claim that Wall Street pain means Main Street gain, and—as we saw during the pandemic and earlier this year—the top earners in the United States really do drive a lot of economic activity. (By one recent estimate, “spending by the top 10% alone accounted for almost one-third of gross domestic product” last year.) None of that means U.S. policy should embrace “trickle-down economics”—whatever that means—or otherwise favor the wealthy over everyone else. But it’s still fascinating to see many on the left—folks who have championed things like taxing 401(k)s—notice that greedy capitalists’ spending and investment can be a major lifeline for middle- and lower-income workers, and that imperiling those transactions can do serious damage to the entire economy.

At least when it comes to Trump’s tariffs.

Summing It All Up

It’s certainly not the case that folks like Chuck Schumer and Elizabeth Warren have suddenly become Hayekian free traders, and I don’t for a second expect them and many other Democrats to start writing Cato essays on downsizing government. Nevertheless, as someone who watches this stuff way too closely, I’ve been struck by the shift in Democratic rhetoric on U.S. trade policy—and not just because the party abandoned its Clintonian views on the issue decades ago. Instead, prominent Democrats—including some of the most populist among them—are smacking Trump’s tariffs from decidedly libertarian angles and doing so in ways that implicitly contradict longstanding, fundamental views on taxes, regulations, and the government itself.

They’re explaining that taxes are ultimately borne by people, not faceless “corporations.” They’re highlighting how regulatory burdens—including complexity—often fuel big business and cronyism, rather than check them. And they’re noting that, while “soak the rich” might make for a great soundbite, it comes with real costs for millions of American workers and the real economy. It’s all very interesting, and these aren’t the only tariff-related epiphanies Democrats have (kinda, sorta) experienced. (I could devote separate columns to policy uncertainty and executive power alone.)

The big question now, of course, is whether these insights will last and whether Democrats will apply them beyond Trump-centric trade policy. Will they rethink antitrust, industrial policy, environmental regulation, and the administrative state with the same clarity? Or will they stick to the same old script when another Democrat is back in the Oval Office?

I can’t say I’m too optimistic—at least not yet—but I surely hope I’m proven wrong. Because while politics may shift, economics remains stubbornly consistent.

Note: Capitolism will be off next week.

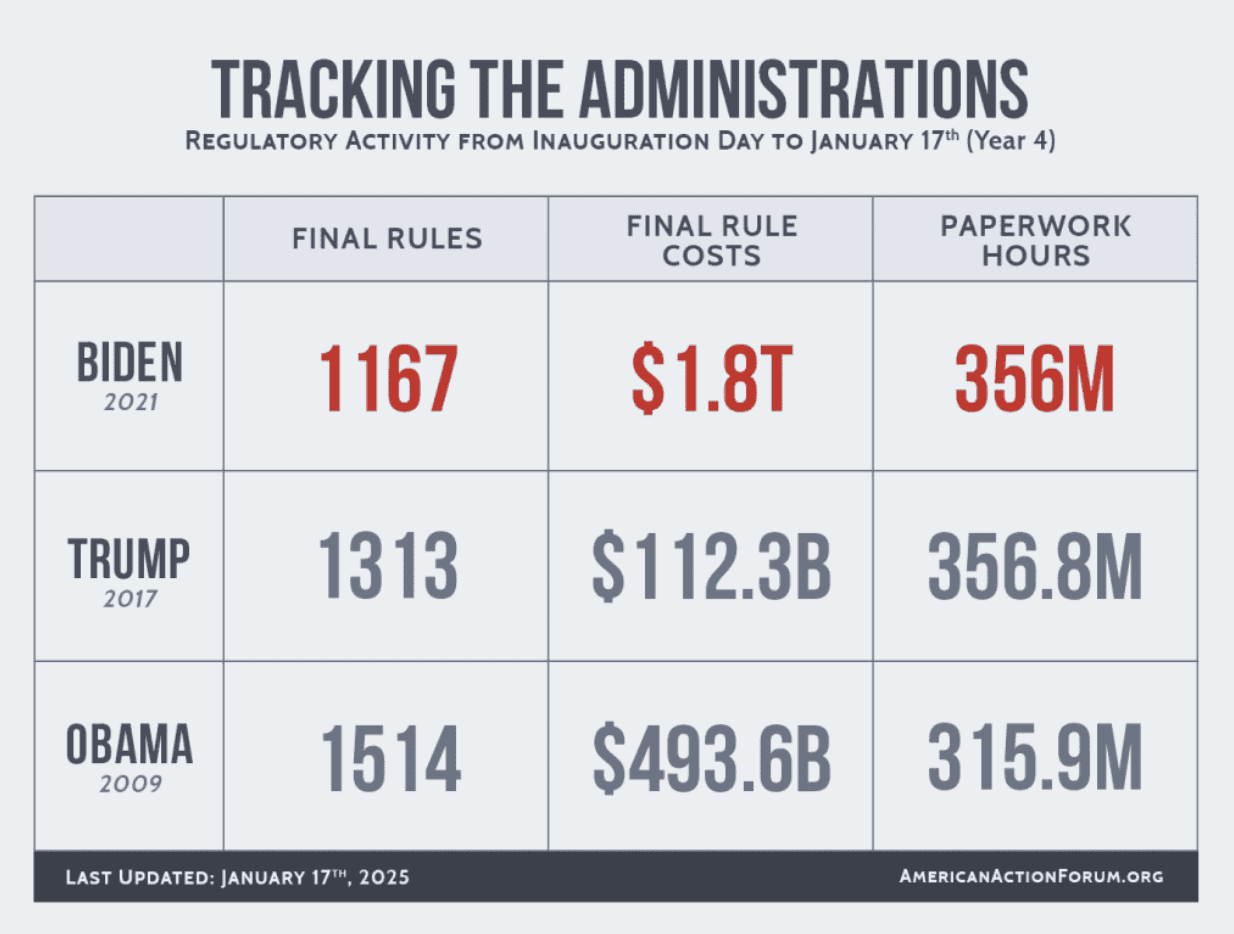

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.