One Wednesday, Donald J. Trump used one of the world’s largest megaphones to announce his bold plan to end vast U.S. trade deficits, lower income taxes, and boost growth by taxing foreign nations that have cheated on trade to enjoy unprecedented surpluses at America’s expense.

The year was 1987.

Trump’s comments appeared in a full-page ad that ran in the September 2, 1987, print editions of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Boston Globe, but they could’ve been printed almost verbatim today. Back then, of course, Japan—not China (“CHYNAH”)—was the target of Trump’s trade ire, but the ad’s themes are almost identical to those on display at Trump’s now-infamous Rose Garden unveiling of his grand “reciprocal tariff” regime—the culmination (for now, at least) of two months of executive branch actions that would’ve increased the scope of U.S. tariffs by almost tenfold.

Since that announcement, markets have gyrated wildly, while dozens of White House officials, media surrogates, and online personalities have offered a wide range of reasons—often contradictory—for why Trump has done what he’s done (all without Congress, of course). Even Trump’s surprise decision today—pausing the worst of the new tariffs but keeping a 10 percent global one in place—is supposedly all part of the plan (whatever that may be).

In reality, however, the reason Trump’s doing this stuff is likely much simpler than what his defenders suggest: He just likes tariffs and always has, and everything else you read and hear about them is just reverse-engineered pabulum to fit (or hide) that singular motivation.

Trump’s Longstanding Love Affair with Tariffs

Trump’s views on immigration, health care, taxes, foreign interventionism, and many other things have changed since the 1980s, but his views on trade have never wavered: It’s a zero-sum game; trade balances tell you who’s winning and losing (surplus good, deficit bad); foreign governments are cheating to win; and tariffs—beautiful tariffs!—can turn the tide in America’s favor, boosting jobs, exports, and growth along the way. He said as much in that newspaper ad; he said it again three years later in a long interview with (lol) Playboy magazine; and he’s said it—in public and private—dozens of times since then, especially during his first term as president. Trump even went so far, Bob Woodward documented in his book, as to famously scribble “TRADE IS BAD” in the margins of a draft presidential speech:

These beliefs were not, moreover, mere rhetoric. They were central to many of Trump’s first-term trade policies. Beyond imposing tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum, washing machines, solar panels, and Chinese goods, Trump’s trade deals reeked of mercantilism (imports are bad; exports are good). His renegotiation of the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement, for example, expanded the South Korean government’s quota on American automobile exports and included new U.S. restrictions on Korean steel and pickup trucks. His mini-deal with Japan, meanwhile, reduced Japanese tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports but did almost nothing on the U.S. side (while maintaining U.S. metals tariffs). His NAFTA renegotiation included some modest trilateral trade liberalization but ignored most U.S. trade barriers and introduced new, protectionist regulations of Mexican labor and environmental practices and of Mexican automotive manufacturing. And his “Phase One” deal with China didn’t eliminate any U.S. (or Chinese) tariffs but instead focused on guaranteed Chinese purchases of U.S. exports to reduce the U.S.-China trade deficit.

These beliefs also motivated Trump’s new “reciprocal” tariffs. As the Washington Post reported last week, the president “personally selected” the new tariff regime, which includes both a 10 percent global tariff and now-paused higher tariffs on imports from countries with which the U.S. has a bilateral trade deficit—a reasonable proxy, Trump’s trade representative asserts, for unfair trading practices abroad. As one White House official put it in the New York Post, the higher tariff rates assume that "the trade deficit that we have with any given country is the sum of all unfair trade practices, the sum of all cheating." Trump himself said much the same aboard Air Force One over the weekend:

I spoke to a lot of leaders—European, Asian, from all over the world. They are dying to make a deal, but I said 'we're not gonna have deficits with your country' ... to me a deficit is a loss. We're gonna have surpluses or at worst we're gonna be breaking even.

The Post adds that, per various insiders, Trump has also been unmoved by the recent market chaos because “he is determined to listen to a single voice—his own—to secure what he views as his political legacy,” one centered on the view that sees “import duties as necessary to revive the U.S. economy.”

Why Trump thinks this way is anyone’s guess. Last week, the Wall Street Journal quoted former Trump officials as tying it all back to his years in Manhattan real estate, where deals were done in cutthroat, zero-sum terms and Japanese investment was a threat. (Many others have suggested the same.) According to Marc Short, chief of staff for former Vice President Mike Pence, “The way [Trump] would describe it is to say … the American marketplace is the greatest marketplace, and people should be charged to have access to it, like a real-estate fee. And we’re suckers not to be charging people not to have access to it.” Another former Trump adviser, Sam Nunberg, added that Trump honed his protectionist instincts by watching “protectionist television personalities, including the late Lou Dobbs on CNN and Fox Business, Laura Ingraham on Fox and the late Ed Schultz on MSNBC,” and that “Trump would remark on how much cheaper televisions were in the U.S. compared with other countries, a differential he blamed on bad trade deals.” His conversations with union construction workers, meanwhile, convinced him that “American workers were being victimized not just by offshoring but by illegal immigrants.” Short recalls that Trump’s economic advisers often tried to dissuade him of his trade “misconceptions,” such as who pays tariffs (spoiler: we do), but Trump would simply refuse to believe it.

Nobody Agrees—And It Doesn’t Matter

Those economic advisers may have failed, but they still had a point: Few, if any, reputable economists would agree with Trump’s core trade beliefs. Almost all trade is between people, not governments, and is positive sum (i.e., both parties benefit; that’s why they trade in the first place). Trade balances—overall but especially bilateral ones—tell us little about foreign trade barriers and “cheating,” because balances are affected by numerous economic and non-economic factors, not just tariffs and non-tariff measures. Foreign governments do impose tariffs and other restrictions on U.S. exports, but the United States is certainly no angel in this regard and the general trend—especially in the developed world—has been toward slowly liberalizing these impediments. And tariffs won’t fix trade balances but will reduce economic growth, exports, and perhaps jobs too on net. (For what international economists think about these issues, UC-San Diego professor and Cato Institute adjunct Kyle Handley has you covered.)

It's thus unsurprising that, in the days following Trump’s reciprocal tariff announcement, economists from across the political spectrum—at banks and corporations and think tanks and universities—pilloried the administration’s methodology, tariff rates, and overall approach. Not only were trade balances a terrible proxy for unfair trade practices, they explained, but the tariff rates themselves were unrealistic, if not absurd. Final “reciprocal” rates, for example, were often far higher than any reasonable estimate of foreign countries’ barriers; tariffs were carelessly slapped on uninhabited islands and U.S. military bases; and nations considered free trade exemplars—and current U.S. free trade agreement (FTA) partners!—were lumped in with notorious trade scofflaws. Small, poor nations ended up with some of the highest tariffs for the trade-crime of simply being too small or poor to buy much American stuff. Many economists further explained that the calculation used to assign the tariffs suffered from several basic—and glaring—errors, and that tariffs would be four times smaller if the proper terms were used (even if you granted their incorrect premise about trade deficits).

The backlash even extended to the economists the Trump administration itself cited to justify its tariff calculations, with many of them openly disagreeing with both the process and results. As one put it, “There’s not a lot of trained economists I know of, including myself, who would argue that trade imbalances are an important metric for policymaking. Yet the people who are setting policy have decided it’s a really important metric.” Another took to the New York Times to lambaste the White House’s efforts, saying that he disagreed with the general policy and that they got his research “very wrong” in multiple ways.

Trump clearly doesn’t care—and, with few (if any) staffers willing to object this time around, neither does anyone in the White House.

But It Still Matters

That Trump has maintained his trade views despite piles of evidence to the contrary and numerous attempts to convince him otherwise—and that those views are singlehandedly driving policy today—is a depressing dynamic for wonks like me, but it’s nevertheless important.

For starters, it should make us very skeptical of popular online theories that U.S. tariffs are part of some grand, multistep strategy instead of just clumsy and ill-justified protectionism (that also helpfully gives Republicans some money for tax cuts). You’ll hear, for example, that Team Trump is actually using the tariffs to engineer “true free trade” (whatever that means), to battle China, or to advance a brilliant and complex plan to rewire the global financial system. Yet, leaving aside some of the rather serious practical and technical holes in these theories, embracing them requires us to disregard decades of Trump’s public and private statements, years of actual Trump policy, the long-held views of Trump’s closest trade adviser (uber-protectionist Peter Navarro), the sidelining of the guy Wall Street thought would keep tariffs in check (Scott Bessent), the wildly contradictory messaging of Trump-whisperers inside and outside the White House, the latest tariff pause (which came after the tariffs hit and seemingly took everyone by surprise), and the not-insignificant fact that there’s been no evidence that the guy actually calling the shots actually wants to achieve any of these other, “strategic” objectives (if he’s even aware of them?). So, either these amazing 3D chess plans are the best kept secret in Washington—one chock-full of intentional feints and distractions—or good ol’ Occam’s Razor applies.

My money’s on Occam.

Coming to terms with Trump’s motivations also gives us clues as to where things on trade might be headed—not necessarily economic Armageddon but probably not great either. Because Trump’s tariffs have been justified on such vague and varied grounds, for example, trade deals with foreign governments (regardless of their substance) might allow for markets to settle, for some tariffs to dissolve, for Trump the dealmaker to claim total victory. And, as today’s pause shows, Trump can quickly enact future changes whenever he wants, regardless of their merits, and his team will have no trouble pretending they were a negotiating masterstroke.

Yet, because the results of all these moves must reflect what Trump already believes, they’ll still likely mean lots of new U.S. tariffs in place and maybe non-market mechanisms like guaranteed purchase agreements or “safeguard” mechanisms (in case trade deficits get too big). Indeed, markets spiked today because Trump suspended some tariffs, but a global 10 percent rate is still in place, as are others on automotive goods and steel and some Canadian and Mexican goods. Others still might be on the way for copper and lumber and maybe semiconductors and pharmaceuticals too. Yesterday, meanwhile, Trump officials said they’ll negotiate something with Japan but were also clear that these deals would still mean new tariffs—no surprise, really, given that many of Trump’s tariffs target U.S. FTA partners with which we have a trade surplus.

The “cheating,” you see, is fine when we do it.

Finally, Trump’s stubborn, peculiar views are a stark reminder as to why, in retrospect, Congress should never have put so much unchecked tariff power into the hands of the president—any president—and why, even after today’s short pause, it should act now to take some of that power back, by veto-proof majority if needed. As I explained last October, there were solid reasons for these delegations during much of the 20th century, and they rested on a then-reasonable assumption that the president—given his deep bench of top experts, national constituency, and foreign affairs responsibilities—would be the government official least likely to embrace crazy, economy-crippling, alliance-busting protectionism. Trump has turned those justifications on their head, in the process demonstrating how these laws can be abused and the economic and geopolitical havoc said abuse can inflict on the world. Politics ensures that passing any such reform will be a massive lift—another reason the power never should’ve been so broadly delegated—and Republicans are already making lame excuses for why their colleagues’ burgeoning trade reform movement should be abandoned. But, as my Cato colleague Matt Mittelsteadt just reminded us, even this GOP has overridden a Trump veto in recent memory, so all they really need is a reason and the proper motivation.

Trump gave them the former; maybe the markets and voters will provide the latter.

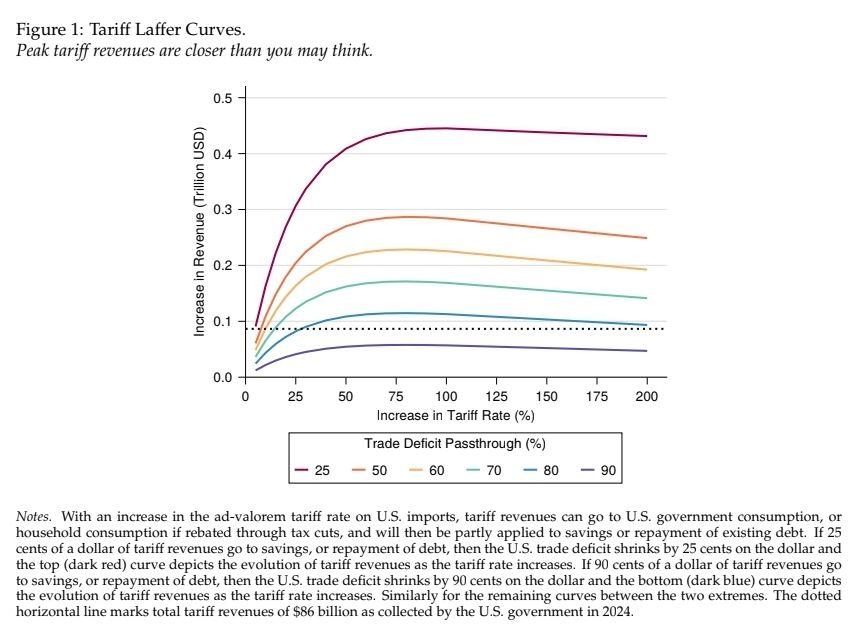

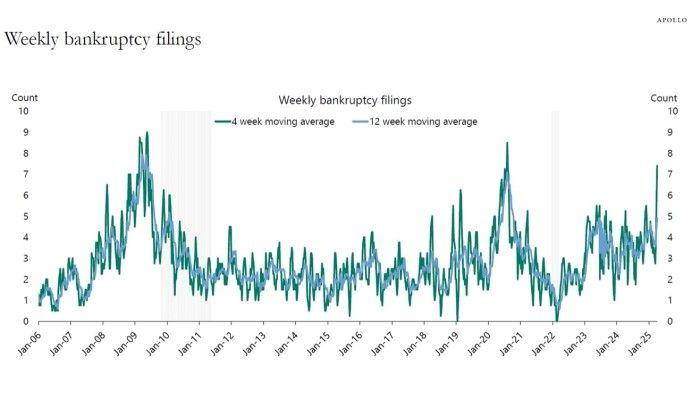

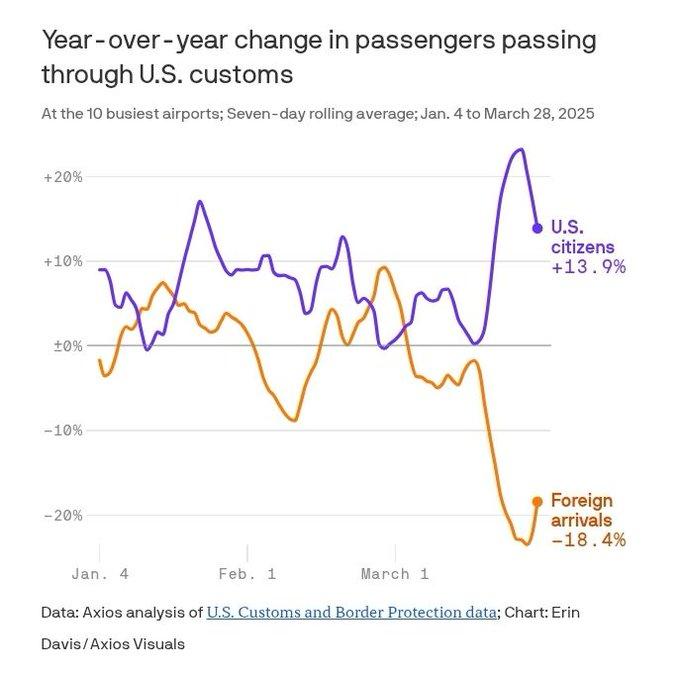

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.