A little more than two years ago, Capitolism first looked with skepticism at claims that artificial intelligence would quickly put millions of Americans out of work and lead to heightened U.S. unemployment. Even today, with American unemployment still historically low despite far more and more advanced AI technologies, the possibility of mass joblessness continues to generate angst. Just last week, in fact, Bloomberg worried that recent hiring pauses at several major companies foreshadowed a coming AI jobpocalypse, while viral charts and politician’s tweets have expressed or evoked similar concerns.

At this point, I’d hope that enlightened Capitolism readers would understand the folly of such predictions, as history is littered with examples of adaptable Americans and our dynamic U.S. economy making similar claims looking silly in retrospect (though discrete churn and displacement is inevitable). In this case, however, recent news has me wondering whether AI—far from stealing all our jobs—might actually mean more of them in the near future, even in industries most affected by the technology.

More, but Different, Tasks

Thus far, AI’s effect on overall U.S. employment has been limited, but new research shows why the technology—at least in its currently foreseeable form—is less likely to replace humans entirely and more likely to supplement our existing work and maybe lead to more workers overall. According to one recent paper, many firms are using AI to perform tasks previously done by human workers, but “the impact on employment is modest” because few firms changed their overall employment levels. Of the firms that did hire or fire people, moreover, “a slightly higher fraction report an employment increase rather than a decrease,” and the authors expect similar trends in the future. Another new study shows that “AI chatbots have had no significant impact on earnings or recorded hours in any occupation” because tasks that AI eliminated were offset by new job tasks, including for some workers who weren’t using the tools themselves.

We see similar things in specific industries. As AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis just documented, for example, people predicted AI would replace medical imaging experts, but instead the opposite has happened:

At the Mayo Clinic, where radiologist numbers have jumped 55 percent since then, AI has become a powerful assistant rather than a job killer. The technology handles routine tasks while doctors retain decision-making authority. Though AI excels at spotting specific abnormalities, it can't replace radiologists' comprehensive role, such as consulting with other physicians, talking with patients, and applying experienced judgment.

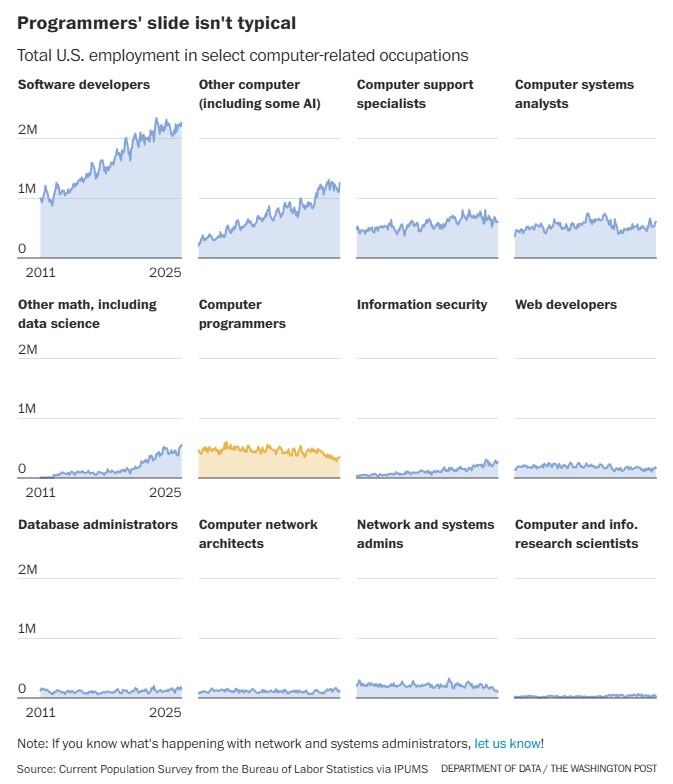

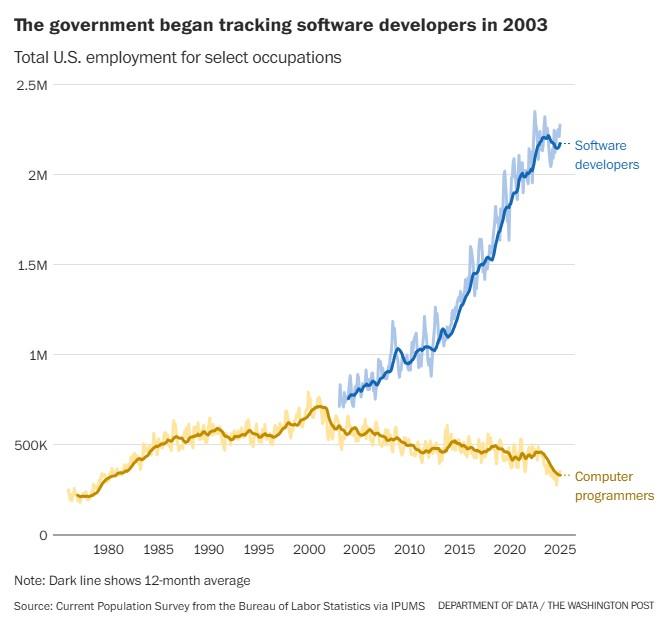

In other cases, certain jobs are eliminated entirely, but they’re more than offset by different job gains in the same industry. In tech, the Washington Post explains, AI seems to have replaced a lot of entry-level computer programmers (insert lame “don’t learn to code” joke here), but those losses were in the “minority” and were “dwarfed” by increases in software developers and workers in closely-related fields.

Here again we see a new division of labor like what emerged in radiology, with humans coming out on top:

[P]rogrammers do the grunt work while the much more numerous — and much faster-growing — software developers enjoy a broader remit. They figure out what clients need, design solutions and work with folks such as programmers and hardware engineers to implement them. Their pay reflects this gap in responsibilities. The median programmer earned $99,700 in 2023, compared with $132,270 for the median developer.

Heightened AI-related efficiency can also lead to more sales and expanding firms, increasing their need for workers:

Research from folks such as Northwestern University economist Dimitris Papanikolaou and his collaborators has found the job market effects of earlier generations of AI and machine learning to be quite muted. The tools make workers more efficient and perhaps even redundant, Papanikolaou told us, but that same efficiency boost also causes the firm to grow, and the growing firm hires more workers. (Not unlike how the laborsaving cotton gin counterintuitively increased demand for the work of enslaved Africans.)

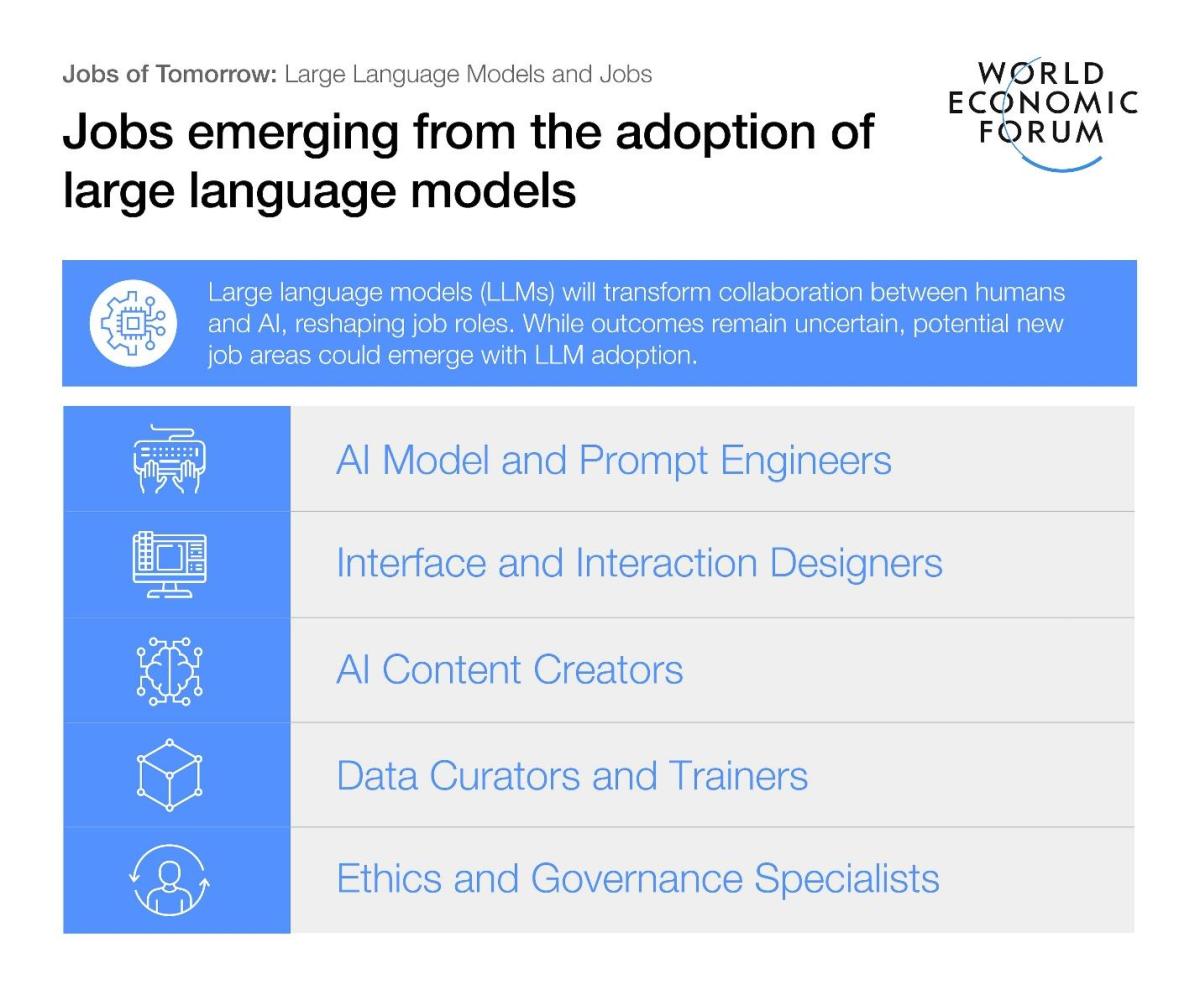

Finally, we could see new jobs in fields that support AI’s deployment. A recent World Economic Forum report, for example, finds three categories of workers that will be needed as AI proliferates: trainers (scientists, engineers, etc., who design AI and related hardware); explainers (people making AI easy to use for the public); and sustainers (people who use, improve, or monitor AI).

Other jobs—including in traditionally blue-collar fields like construction—will also be needed to build the infrastructure (data centers, cloud architecture, energy, etc.) that AI demands.

New, or Expanded, Markets

The second way that AI might increase demand for workers is through the expansion of services that—because of the massive cost (time, money, manpower, etc.) of acquiring certain skills or knowledge—were once available to only the wealthy, trained experts, or huge companies. My Cato colleague and tech policy expert Jen Huddleston calls this process “democratization” and says you can see it most clearly in how small-business owners are embracing AI to “outsource” tasks—data analysis, expense reports, image generation, customer service, cybersecurity, etc.—that used to take them hours each day or ones that they couldn’t do at all.

To see how this works in practice, consider a new AI-powered app called “Valuable” created by friend of mine that allows individuals (collectors, hobbyists, inheritors, etc.) or small businesses to quickly price, organize, and sell antiques, collectibles, furniture, and more by simply snapping a picture of the item at issue. A small-time collector of political memorabilia himself, my buddy was annoyed by how difficult it was for him—and basically anyone outside Sotheby’s or Antiques Roadshow—to know how much an item was worth and where to sell it. Enter the AI-powered Valuable App, which—among other things—trolls millions of disparate online listings and lets smartphone users quickly identify an item, know its market price and when/where best to sell it, and get other relevant information about the market at issue. He tells me that this kind of assistance was unavailable to normies before AI came along, because even simple searches would take rooms full of humans working 24-7 to make it work. (No, he’s not paying me to write this, though he did give me a free glass of wine at the app’s launch party.)

Other industries, such as book publishing and filmmaking, are seeing similar kinds of democratization. By allowing almost anyone to have access to new tools and services, AI will potentially mean more entrepreneurs, more products, and even entire business models that couldn’t exist just a couple years ago. And that, in turn, can mean not only more jobs running a small business but also demand for employees at these new firms to do the tasks AI can’t handle.

More, and Healthier, People

Finally, there’s the simple fact that, by processing vast amounts of data at incredible speeds, AI will improve human health and longevity in breathtaking ways. R Street’s Adam Thierer sets the stage:

No matter how it is quantified, it is clear that medical and health-related information is exploding. The only way to take full advantage of this growing body of knowledge is with the power of [AI and machine learning], specifically with machine-reading technologies that can more quickly sift through immense datasets to find meaningful signals in the noise. As the National Cancer Institute summarized, “[W]hat scientists are most excited about is the potential for AI to go beyond what humans can currently do themselves. AI can ‘see’ things that we humans can’t, and can find complex patterns and relationships between very different kinds of data.”

This technology has been around for just a few years now, and already it’s helping people with chronic, once-debilitating conditions participate more fully in the formal economy. It’s improving the ability of those with disabilities to live, work, go to school, and travel more fully and independently. It’s helping “speed up stroke detection and diagnosis and coordinate care teams to get patients the treatment they need sooner, saving millions of brain cells and improving patient outcomes.” And it’s helping people like Tom Rosenblatt, who at just 30 was sidelined by inexplicable chronic pain:

AI already is being used to read X-rays and help develop new drugs. I needed it to sort through a mountain of daily pain logs, sleep patterns and academic studies. Each morning, I would note whether migraines spiked after a midnight snack or if magnesium supplements helped. Claude’s pattern analysis spotted connections that time-crunched doctors simply aren’t equipped to see.

A study of 2008 data found that chronic pain costs today’s U.S. economy about $900 billion a year, adjusted for inflation. That’s more than heart disease and cancer combined, according to the National Academy of Medicine. One in 5 American adults—50 million people—live with chronic pain. Our healthcare system is great at treating broken bones but falters when dealing with lingering aches and fatigue. Who unifies the data from many specialists? Meanwhile, physicians—nearly half of whom report burnout—juggle thousands of patients. These doctors don’t have time to parse months of smart-watch logs during a 15-minute appointment.

Rosenblatt used AI to do the things doctors can’t—track treatments, uncover patterns, and suggest interventions—and he’s today able to think more clearly and get on with his life. Millions of other Americans, he adds, will eventually enjoy similar benefits, with corresponding gains for the U.S. economy along the way.

AI is also helping us live longer. It’s enabling earlier detection and diagnosis of fatal diseases. It’s using selfies—no, really!—to help people take better care of themselves or know when to see a doctor, and to help those doctors improve their patients’ treatments. It’s “dreaming up new drugs no one has ever seen” and using old drugs to create new “lifesaving regimens” that human doctors had never considered.

It’s miraculous stuff, and it might mean more American jobs, too. As we discussed with deportations, for example, humans are not just a source of labor supply but also a source of labor demand (thus explaining why deportations depressed economic activity in immigrant-heavy cities). More people able to live and work longer means more people able to buy local goods and services, which means more demand for people to work in related industries.

It also means, as we’ve discussed regarding our continued Superabundance, more potential for specialization and innovation—a big reason an increasing global population has accompanied increasing wealth and longevity and still plenty of jobs. “Even if only a small fraction of humans can generate a good idea,” Superabundance authors Gale Pooley and Marian Tupy write, “the number of good ideas will grow in proportion to population growth.” And AI, again, will mean more humans.

Summing It All Up

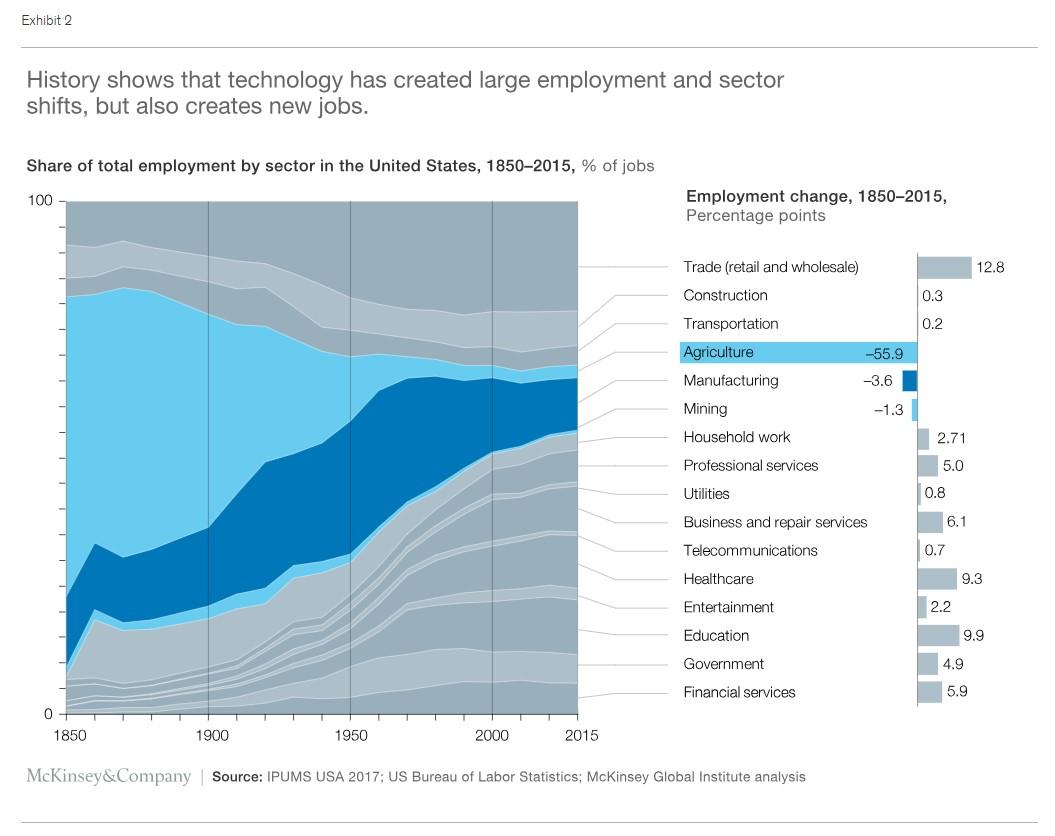

Worry about tech-driven joblessness is surely nothing new. As economist Tim Taylor reminds us, “just a few years ago, before we were concerned that AI would take all the jobs, we were worried that new robotics technologies would take all the jobs. And before that, we were worried that automation would take all the jobs.” Such fears, in fact, go back centuries and—as this killer chart from McKinsey shows—they keep being proven wrong:

As we discussed in early 2023, this history alone gave us reason to doubt that AI would usher in an era of mass unemployment, and the last two-plus years have proved such skepticism to be warranted. The technology will surely kill off certain tasks and even certain occupations, just as mechanized farming, industrial robots, computers, and the internet did in previous eras. But—as any decent wonk can tell you from experience—AI’s advances (and, thus, adoption) have been slower than the worriers assumed, and markets and people will likely adjust to the disruptions that do eventually come. That adjustment, in fact, is happening right now.

Even more interestingly, I think, is that far from boosting U.S. joblessness, AI might actually increase demand for workers in the years ahead, by supplementing our work, making us wealthier and more efficient, democratizing services once utilized by a privileged few (if at all), and helping us lead healthier and longer lives. If so, it’d also track past technological advances that have helped fuel today’s superabundance, thus making that future’s most likely impediment not some sort of economic dystopia but the people and governments that worry about it too much and thus want to stop progress in its tracks.

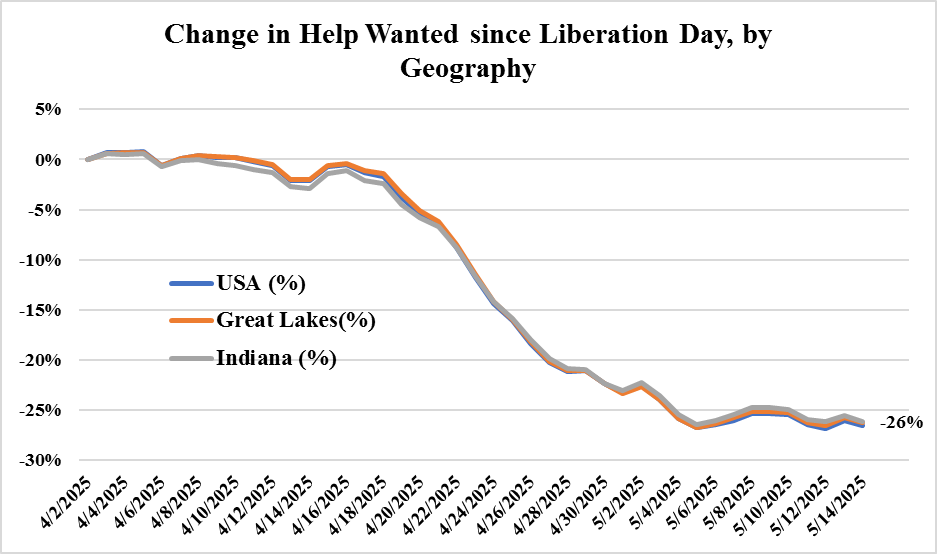

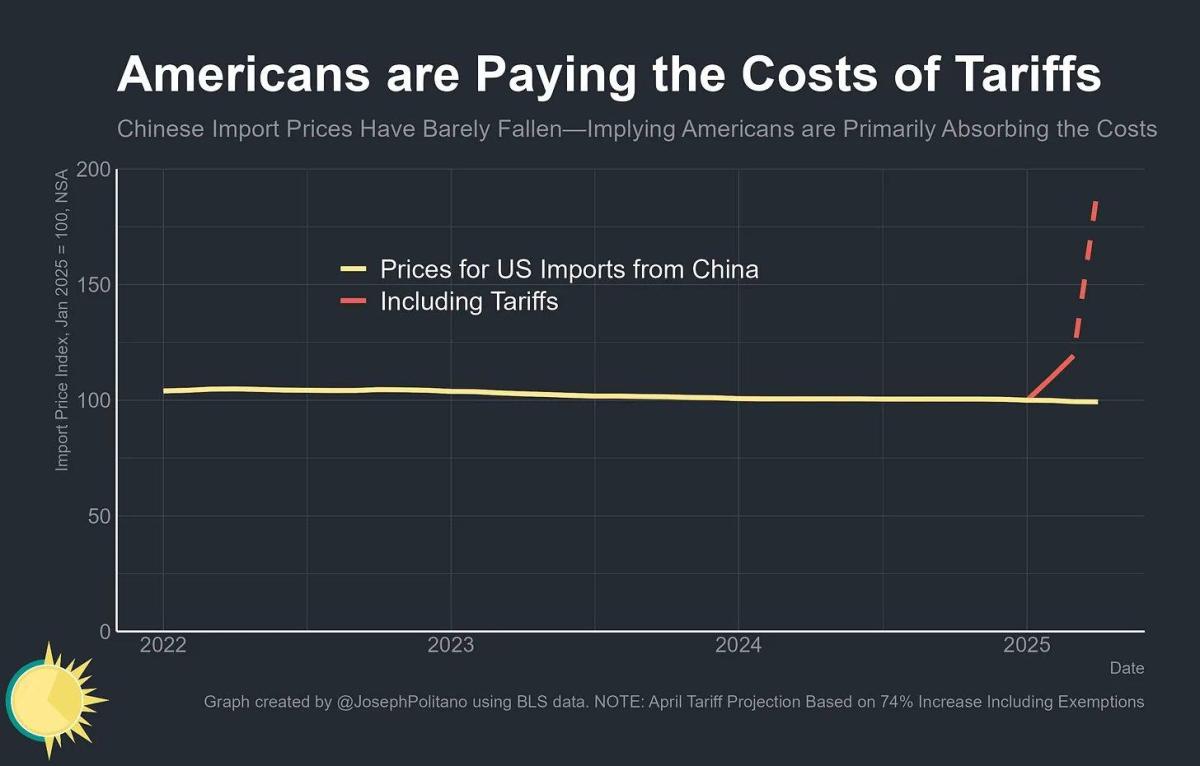

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.