Hello and happy Sunday. As Hurricane Helene and its remnants made their way into Florida and through the South, my neck of the woods in East Tennessee is hurting (as are nearby places like Boone and Asheville, North Carolina). Though my family and I are safe, we know folks who have lost their homes, some who have been forced to evacuate to escape floodwaters, and others who—as I write this—are totally cut off by rivers that haven’t been this high since records have been kept.

It’s heartening to see folks scrambling to do whatever they can to help their neighbors as emergency workers and civil servants risk their lives to help others. For you readers who are the praying sort: We’d appreciate your prayer.

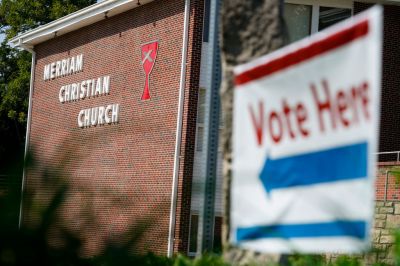

There’s really no smooth segue I can make into this week’s Dispatch Faith essay, but being neighborly in good times and bad—or perhaps one could say being a good citizen—is really at the heart of it. As we enter the final few weeks of this election season, author Jen Pollock Michel lays out why, especially in an election like this one with no truly good options for president (again), faithful ambivalence is entirely appropriate. And that to her, being a good citizen is about more than just being a voter.

Jen Pollock Michel: Is Lapsed Patriotism Lapsed Faith?

When the Nazis enacted the Aryan Paragraph in April 1933, the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer left for England and stayed nearly two years. In June 1939, he left Germany again, this time traveling to the United States to avoid military enlistment.

But just eight days after arriving in New York that summer, Bonhoeffer resolved to return and this time, remain in Germany. He boarded a ship, writing in his diary that his “inner ambiguity about the future has ceased.” Bonhoeffer came home, not simply because he was a Christian, but because he was a German Christian.

“His ache was the agony of responsibility,” Laura Fabrycky writes in her book, Keys to Bonhoeffer’s Haus. “He knew his actions mattered.”

To be clear, Bonhoeffer’s moment is not ours. Though we are facing a consequential election, we can compare neither presidential candidate to Hitler. Still, Bonhoeffer’s “inner ambiguity” when crossing the Atlantic in 1939 captures my orientation today as an American Christian, facing the 2024 electoral prospects and dire predictions about the fate of democracy. Indeed, it’s Bonhoeffer’s “inner ambiguity” that permits this public confession: While Bonhoeffer resolved his own “inner ambiguity” by returning to Germany and engaging in active political resistance, I have instead secured a Canadian passport and prepared for possible expatriation.

Is my lapsed patriotism lapsed faith?

To situate my own story a little, I am an evangelical Christian, born and raised in the United States, in various small towns and mid-sized cities across the American South and Midwest. In the pews of my (segregated) Southern Baptist churches growing up, I nursed on the story of American greatness, pledging allegiance to the flag that hung in every sanctuary in which we worshiped. I believed our country was great for where we’d laid our national trust, though I also learned that the gospel of Jesus Christ sends his disciples beyond the borders of home and country. Because for as much as Southern Baptists love America, the denomination is also fiercely committed to the Great Commission. This is what Christians call Jesus’ final parting injunction when, after his resurrection, he takes leave of his disciples. “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations.”

I met my husband at Wheaton College, a bastion of American evangelicalism, and he, too, had been raised with similar patriotic and missionary fervor. Although we weren’t going to the ends of the earth when we married, when a work opportunity was proposed in Canada in 2011, our family took it. We left the United States, Barack Obama still president, and never imagined how much would change in us and in the country during our absence, especially after the election of Donald Trump in 2016 with broad evangelical support.

Our expatriation was intended, at first, to be short-term. But three years became five, five years became eight, eight years became 11. We would likely have stayed in Toronto apart from the call to care for an aging family member in 2022, though when we made the decision to return to the United States, we ensured our right of return to Canada by beginning paperwork for Canadian citizenship.

By then, of course, our understanding of “Christian” political commitments had inevitably shifted. This might have been predicted, given that human beings are imitative creatures. Our behavior, as the late French academic René Girard argued, is mimetic, and our visions of the good life are influenced by others. Though 38 years in the United States had enshrined in me a sense of the obvious, unequivocal good of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” 11 years in Canada forced me to consider the Canadian ideals of “peace, order, and good government.” It’s true that I never longed for those three things more than on January 6, 2021, when, from my dining room table in Toronto, I watched news reports of the storming of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. This was not the America I’d once loved or the gospel I’d been taught.

To be clear, this isn’t a panegyric about Canada as an exemplar of moral government. Since 2015, when the Supreme Court of Canada legalized physician-assisted death, it has expanded beyond its original legal boundaries. The number of patients electing to die has grown year over year. Protection has been whittled for doctors with conscientious objection, substantiating some of the conservative sky-falling in the United States, where there is active worry over eroding moral commitments and the overreach of government.

No, my question isn’t about one nation’s superiority over another. Instead, it concerns the allegiance I owe as a Christian to any nation. How should I understand the rights and responsibilities of citizenship? And what is the consequence of a vote?

These aren’t questions explicitly answered in the Bible or in early Christian history, given the persecution of the growing sect. We do know, however, that political affiliation in the United States has grown into a too-easy measure of moral character. As David Zahl cites in his 2019 book Seculosity, fewer than 10 percent of American parents in the 1950s would have objected to their child marrying someone from another political party. In 2010, that number surged to nearly 40 percent. Today, entire church congregations are turning over, resorting themselves according to shared political ideals. This was certainly the divided landscape our family faced when we began looking for a church in Cincinnati in 2022. Where would we worship—and would we be welcome, given that MAGA politics was the new orthodoxy in many evangelical spaces?

I’m coming to believe that a degree of Bonhoeffer’s “inner ambiguity” may be the most reasonable orientation when people of faith face the prospect of political responsibility. We are citizens of Christ’s kingdom before we are citizens of any country. Insofar as Bonhoeffer’s moment speaks a political word, it would seem to caution against the “fanatical,” a word which, according to Fabrycky, shifted in meaning and came to connote the goodness of “one’s intense personal loyalty to Hilter and the Regime.” Part of the danger of fanaticism is its laziness, its unwillingness to grapple with moral complexity. Fanaticism is like the photo-negative vice of acedia, the deadly sin Fabrycky identifies in her book.

Acedia, as identified by the earliest monks, is defined as the failure to care. While a fanatic invests too much moral certainty and emotional investment in his choices and cannot stomach alternatives, a person suffering from the “noonday demon” flags in spirit. They can’t be bothered to give a damn—about their nation or their neighbor.

So to be politically ambivalent, as I have argued, isn’t to be politically indifferent. It is, however, to have any fanaticism chastened and to assume a sobered “two-mindedness.”

To be human is to choose with great freedom—and to choose with limited knowledge. In other writings, Bonhoeffer argued that a theology of human responsibility grants a complicated—and often contradicted—freedom. Freedom engenders risk. Lacking moral certainties (as we often do), our participation necessarily implicates us in ways we may never intend. It is to say that human life, and maybe especially political life, dirties our hands. In many cases, against our most earnest, even righteous desires, we choose wrongly and unwisely.

As a Christian, I’m inclined to think that voting for our next American president, while an important democratic freedom and one I intend to exercise, may not be the greatest civic good I can offer. A vote is invariably an expression of compromise, not conscience. It is certainly not the course of self-justification many insist it is, proving (or disproving) my personal probity. Indeed, if I see my responsibilities to neighbor as well as to nation, I am also to consider many forms of “civic housekeeping,” as Fabrycky vividly calls it in her book. As Jesus said, when distilling the essence of God’s law, to love God is also to love one’s neighbor.

It is to see in the face of the stranger the very face of God.

As an example, much like the city of Springfield, Ohio, has seen an influx of immigrants, our new city of Cincinnati has seen a dramatic uptick in Mauritanian asylum seekers. These men have arrived as the hungry, the lonely, the jobless, the traumatized—the kinds of marginalized people for whom Jesus always showed intense concern. I have heard stories from many of these men, whom our church has served through English classes, bike donations, and employment services. Their stories include liquidated assets, left-behind families, brutal beatings, and treks across hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles. Living as many as 10 in a single one-bedroom apartment, they seek hope and work and better lives for their families.

It’s these men I thought of when our congregation collectively prayed a prayer on the Sunday after Independence Day. Written by W. David O. Taylor in his book, Prayers for the Pilgrimage, the prayer expresses how Christians might rightly situate their loyalties. “O Lord, you whose kingdom is not of this world. Strengthen our allegiance to your kingdom, we pray, deepen our loyalties to your global body and increase our longing for a better country, so that in Jesus’ name, we might love our nation and our neighbors as pilgrims in a strange land.” As we prayed together, we were rehearsing our identities, first as Christians. We were calling upon God, not simply to bless our country, but to favor the world—indeed, the nations to which we, as Christians, had been sent and who were now at our doorstep.

As-salamu alykum, our new Mauritanian friends always say in response to our efforts to help. They fold their hands and cast their eyes to the sky. Yes, we tell them in reply. May God bless you.

When I enter the ballot box this November, I won’t be thinking of the claims of the nation—but the commitments of faith. And wherever I may choose in the future to live, I will remember that I am not a patriot or partisan—but a little Christ.

Mark Tooley: A New Methodist Denomination Emerges

This week in Costa Rica, the Global Methodist Church (GMC) held its first ever general conference. The new denomination formed in 2022, as a result of a split with the larger United Methodist Church (which you can read more about here), following years of internal conflict. On the website today, Mark Tooley explains the biggest decisions the Global Methodist Church made and how it will look very different from the United Methodist Church of old.

So, founding a new denomination with traditional ecclesiology is a move against the headwinds of current American religious preferences. Why should Christians be specifically Wesleyan and submit to the accountability of a formal denomination with doctrine and rules?

Having to make these arguments will be healthy for the GMC, because Methodism occupies its own spiritual niche. Methodism has traditionally emphasized that salvation, personal holiness, and sanctification are available to each person; that prevenient grace guides people even before they become Christians; and that all good things, including social renewal, are possible through God. Unlike Baptists and most nondenominational churches, the Methodist church baptizes babies, esteems liturgy, recites creeds, and ordains women. It’s open to, but does not mandate, charismatic worship. It tends to be egalitarian and optimistic.

Is there a significant place for Methodism in future U.S. Christianity? The GMC will help answer that question.

More Sunday Reads

- When it comes to religious demographics, the U.S. is experiencing something completely new, as Ruth Graham reports for the New York Times: “For the first time in modern American history, young men are now more religious than their female peers. They attend services more often and are more likely to identify as religious.‘We’ve never seen it before,’ Ryan Burge, an associate professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, said of the flip. Among Generation Z Christians, this dynamic is playing out in a stark way: The men are staying in church, while the women are leaving at a remarkable clip. Church membership has been dropping in the United States for years. But within Gen Z, almost 40 percent of women now describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated, compared with 34 percent of men, according to a survey last year of more than 5,000 Americans by the Survey Center on American Life at the American Enterprise Institute. In every other age group, men were more likely to be unaffiliated. That tracks with research that has shown that women have been consistently more religious than men, a finding so reliable that some scholars have characterized it as something like a universal human truth.”

- In vitro fertilization and other fertility treatments have been big topics of conversation in the U.S, but women freezing their eggs so they can have children later is becoming more common in Islamic countries as well, as Sonia Sarkar writes for Religion Unplugged: “Several factors have led to the rising trend of women in Islamic countries opting for social egg freezing: Increasing education among women, larger participation of women in the labor-market force who are keen to build a career for themselves, and the choice to delay marriages and raising children are some of them. The other important factor is increasing social acceptance. In 2021, for example, the [United Arab Emirates] introduced a law that allowed single women to freeze their eggs for both health and social reasons. As per the law, the initial cryopreservation period is five years and can be extended by another five. But these single women are permitted to use the frozen eggs solely for their own pregnancy after marriage with their husband’s sperm in an IVF procedure.”

A Good Word

The ties among religion, art, and food are intrinsic and often fascinating. A new exhibit in the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) looks to highlight those bonds in the Islamic world. “Of all of the exquisite pieces in ‘The Art of Dining: Food Culture in the Islamic World,’ which opened Sunday at the DIA, some of the most exquisite are also some of the smallest,” writes Khristi Zimmeth for the Detroit News. “It’s hard not to ogle items like the bird-headed spoon made of jade in India about 1600, inlaid with gold and set with rubies and emeralds, from a collection in Kuwait, or a delicate 4-inch glass bowl from 9th-century Egypt, on loan from London’s Victoria & Albert and marvel not only at the detailed work that must have gone into creating them but also the fact that they have been gathered from around the world for us to enjoy centuries later. Exploring and celebrating Islamic art through the lens of food and culinary culture, the exhibit includes approximately 230 works from the Middle East, Egypt, Central, South and East Asia and Europe. It illuminates connections between art and cuisine from ancient times to the present day, demonstrating how food transcends cultures, backgrounds and borders.” Veronica Esposito had another fun read about the exhibit for the Guardian that’s worth your time.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.