Amid the decline of nearly all U.S. Protestant denominations, both liberal and conservative, the new Global Methodist Church (GMC) has emerged and last week convened its first governing general conference in Costa Rica. Although about 80 percent of its 4,733 congregations are in the U.S., the approximately 350 delegates met outside the U.S. to stress the new church’s international identity and to facilitate visas by African delegates.

The GMC’s creation in 2022 resulted from the schism of what was once America’s third largest religious body, the United Methodist Church. More than 7,900 congregations, with their property, have exited the denomination so far under a temporary process that officially ended in 2023, although several local regions allowed more exits this year (7,658 left by 2023, and 274 exited this year).

Of these exited U.S. United Methodist churches, roughly 3,700 so far have joined the new GMC. Why not more? Many churches, exhausted after the exit process, postponed any decisions about joining a new denomination. Another 1,000-2,000 U.S. churches ultimately will join the GMC. But hundreds of former United Methodist churches will stay independent or form informal networks.

Methodism historically is not congregationalist. Like Presbyterianism, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism, among others, it has a connectional ecclesiology (theology of church organization and governance). In the system originally established by 18th century Church of England evangelist John Wesley, the churches are owned by the denomination. And Methodist congregations traditionally are governed collectively by regular “conferences,” often officiated by bishops.

After decades of contentious debates over sexuality, many of those who left the United Methodist Church were disenchanted by their captivity to a divided and shrinking denomination. One long besieged Maryland pastor told Christianity Today that after years of fighting and having “ to go the microphone to fight. It’s hard to let go of that.”

But delegates at the GMC General Conference across six days seemed to feel joyful and hopeful.

First, they seemed to feel liberated. As clergy and laity, they had labored for decades in an increasingly theologically progressive denomination where traditionalists often felt stigmatized. Many had served as delegates to United Methodist general conferences. A Michigan pastor and counselor told Christianity Today that some of the GMC delegates evinced “post-traumatic stress.” The United Methodist Church this year removed bans on same-sex marriage and gay clergy. Global Methodism’s official standard is that “human sexuality is a gift of God that is to be affirmed as it is exercised within the legal and spiritual covenant of a loving and monogamous marriage between one man and one woman.”

During the conference, delegates rejoiced in exuberant worship and praise music, often with arms uplifted. This somewhat charismatic worship style is not typical even for most evangelical or conservative Methodist congregations. Most such churches are still fairly sedate and liturgically Mainline Protestant, with organ music and often solemn silence. But Global Methodist leaders when they gather are more freewheeling, somewhat reminiscent of early Methodism in Britain and America, in which revivals often included dramatic emotions and outbursts. The delegates in Costa Rica were fully united with many overseas delegates, especially from Africa, whose own worship style is likewise exuberant. The name “Global Methodist” is no accident. United Methodism’s global nature, with millions of church members in Africa, long kept it from liberalizing on sexuality issues, as other Mainline Protestant denominations did years ago. These battles built strong alliances and friendships between American evangelical United Methodists and their brethren in Africa.

United Methodist progressives resented the growing African influence in their denomination, which blocked their legislative agenda, especially on sexuality. When progressives lost at the 2019 United Methodist General Conference thanks to African votes, a bishop referred to the traditionalist agenda as a “virus.”

But Global Methodism sees Africa as central to its future. About 20 percent of Global Methodist churches are overseas, mostly in Africa but also including small numbers in Eastern Europe and the Philippines. There will be more.

In May the 1 million-member United Methodist church in the Ivory Coast quit the old denomination. In June, Nigeria Episcopal Area, with reportedly 600,000 members, also quit United Methodism, though dissenters pledged to remain in the old denomination. A smattering of other churches in Africa have quit the old denomination, with most others yet to decide. Many painful and divisive decisions lie ahead.

Ivory Coast had said it will remain independent, while Nigeria’s bishop has joined the Global Methodist denomination. Africa’s bishops are paid by the U.S. church and are inclined to stay in the old denomination. Clergy and laity, meanwhile, are overwhelmingly conservative, especially on sexuality.

The only real potential controversy at the Global Methodist General Conference was how to organize bishops. Some exited United Methodists, wary of some of the fights in the United Methodist Church, preferred no bishops. But GMC leadership preferred Methodist tradition, which dates to America’s first Methodist bishops in 1784, most notably the tireless circuit rider Francis Asbury. Under Asbury, Methodism became America’s largest religious movement in the early 19th century.

Two former U.S. United Methodist bishops were already full-time, overworked GMC bishops, and in July they were joined by the exiting Nigeria United Methodist bishop. To help these three bishops, the GMC at its general conference elected six part-time new interim bishops who will serve until the next general conference in 2026. They include two U.S. women, one black U.S. man, a white U.S. man, and two African men. The election of Kimba Everiste of the Democratic Republic of Congo was especially moving, as his friendship with U.S. evangelicals led to removal from ministry by his Congolese bishop, who’s aligned with U.S. progressives.

The GMC general conference also chose a new way to handle bishops. United Methodist bishops, as in most denominations, preside over geographic regions. GMC bishops will not administer local areas but serve as itinerants for the whole church as teachers and guardians of Methodist doctrine, with each bishop focused on five or six regions.

Local conferences will be administered by superintendents. This somewhat replicates U.S. Methodism prior to the 1939 merger of the northern and southern churches, which split in the 1840s over slavery.

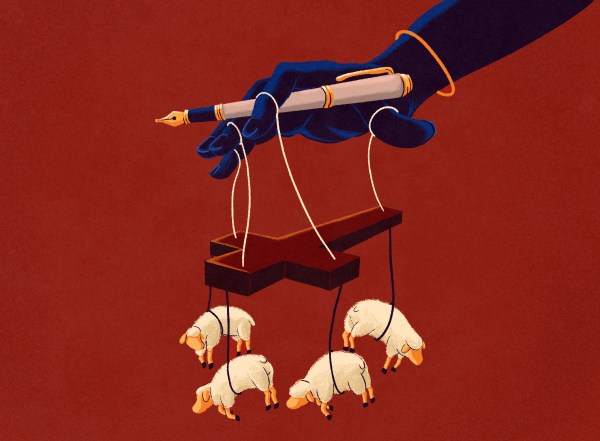

Under the reunification, the South had feared governance by northern bishops, and hence preferred its own bishops. But across decades, bishops with the power to appoint all clergy, sometimes with little say by local churches, often grew both theologically and politically progressive, occasionally at odds with more conservative laity and clergy who were in the minority. With bishops now specifically delegated to guard the church’s doctrine, the GMC hopes to avoid what it sees as Mainline Protestantism’s decline into heterodox theology that deemphasized salvation and personal holiness, which were historic Methodist emphases, in favor of social reform.

As exited United Methodist churches and regions around the world make decisions, the GMC will continue to grow. The bishop of Russia’s 80 Methodist churches, which quit the old denomination this year, said they will decide on GMC affiliation in April. Churches in Cuba and Costa Rica, which are independent, will remain so but have relations with the GMC, which is theologically more aligned with them than the United Methodist Church.

The 2026 general conference will be in Africa. But the GMC still faces the challenge of arguing for a denomination and a particular theological tradition at a time when U.S. Christianity is becoming generically evangelical and increasingly nondenominational. If nondenominational churches were collectively a denomination, they would now be America’s largest, comprising, according to one estimate, 13 percent of American churchgoers.

So, founding a new denomination with traditional ecclesiology is a move against the headwinds of current American religious preferences. Why should Christians be specifically Wesleyan and submit to the accountability of a formal denomination with doctrine and rules?

Having to make these arguments will be healthy for the GMC, because Methodism occupies its own spiritual niche. Methodism has traditionally emphasized that salvation, personal holiness, and sanctification are available to each person; that prevenient grace guides people even before they become Christians; and that all good things, including social renewal, are possible through God. Unlike Baptists and most nondenominational churches, the Methodist church baptizes babies, esteems liturgy, recites creeds, and ordains women. It’s open to, but does not mandate, charismatic worship. It tends to be egalitarian and optimistic.

Is there a significant place for Methodism in future U.S. Christianity? The GMC will help answer that question.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.