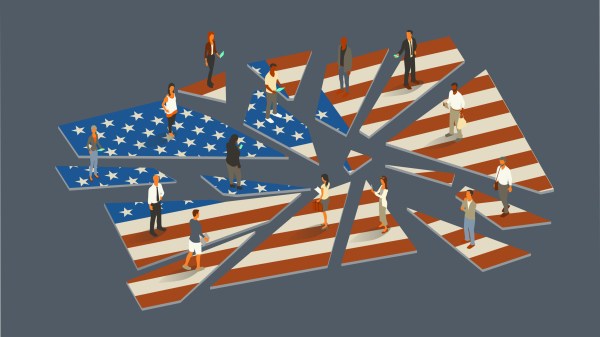

Hello, and happy Sunday. That the United States’ religious makeup is changing is well known by now. We certainly see evidence of it in clashes in the public square and even political realignments, evidenced in this month’s elections.

But along with conflict, the changes can offer new opportunities for cooperation, which is what scholar Asma Uddin addresses in today’s Dispatch Faith. Often when scholars encourage cooperation among different faith groups, it’s done in a way that flattens out important theological differences. But sometimes competing claims about the truth—who is God, for example—cannot be reconciled with one another. And a religious pluralism that tries to erase those distinctions really is no pluralism at all. But as Uddin writes today, groups that disagree on such ultimate questions can still work toward common goals, even as the landscape around them continues to change.

Asma T. Uddin: Now Is the Time for New Interfaith Connections

Over the past few decades, the religious landscape of America has transformed in ways we couldn’t have imagined. Historically, Christian groups—particularly white evangelical Protestants—wielded significant influence in public life. Leaders like Jerry Falwell Sr., for instance, helped shape social policy through the Moral Majority movement in the late 1970s and 1980s. Their churches often served as de facto community centers, and their leaders’ endorsements were actively sought by political candidates.

Today, Christianity is no longer the cultural powerhouse it used to be. While white evangelical Christians remain politically significant and played a crucial role in both Donald Trump’s 2016 victory and last week (coming in at more than 80 percent each time), their ability to shape broader cultural narratives and social norms has diminished significantly, particularly among younger generations and in major urban centers.

According to the Pew Research Center, in the 1990s, almost 90 percent of Americans identified as Christian. Today, that number has dropped to below 65 percent. Even more striking is the decline among white Christians, who now make up just 42 percent of the population. At the same time, the number of people who don’t affiliate with any religion has skyrocketed, and minority faiths are growing in both numbers and visibility.

This demographic transformation demands new approaches to religious cooperation and civic engagement. Faith groups now face a critical question: How can they maintain authentic religious identity while participating meaningfully in an increasingly pluralistic public square?

The Harvard Pluralism Project, founded in 1991 by Diana Eck, offers a framework for understanding this challenge. According to the project, true pluralism involves five essential components. First, pluralism requires more than just acknowledging diversity—it demands active participation and exchange between different groups and traditions. Second, while tolerance is important, pluralism pushes beyond it to require deeper understanding and substantive knowledge of different beliefs and practices. Third, pluralism supports strong individual religious and philosophical commitments, rejecting the notion that embracing diversity means watering down one’s own beliefs. Fourth, American pluralism is grounded in First Amendment principles, creating space for ongoing discussion rather than demanding agreement on matters of faith. Finally, pluralism depends on fostering meaningful dialogue that illuminates both shared values and fundamental differences, with all parties willing to engage while maintaining their distinct perspectives. This framework envisions a dynamic society built on engagement across differences, rather than mere coexistence.

Though there are plenty of examples in American history, interfaith cooperation has evolved over time. Early efforts, such as the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions and mid-20th century ecumenical movements, often sought to minimize religious differences or find theological common ground. The National Conference of Christians and Jews (now the National Conference for Community and Justice) initially focused on finding theological similarities between faiths, while the World Council of Churches emphasized doctrinal reconciliation.

Modern coalitions take a markedly different approach, one that aligns with what the Pluralism Project at Harvard University describes as “the encounter of commitments.” Instead of trying to reconcile theological differences, they focus on shared civic goals while respecting each group’s unique religious identity. The Shoulder to Shoulder Campaign exemplifies this evolution, bringing together Christian, Jewish, and Muslim organizations to combat anti-Muslim bigotry while explicitly recognizing theological differences. This represents a fundamental shift from unity through theological compromise to unity through shared civic purpose.

The International Religious Freedom Roundtable illustrates another dimension of this new model. Its monthly meetings bring together diverse faith groups, secular organizations, and policy experts to coordinate advocacy efforts on religious freedom. And again, rather than seeking consensus on theological matters, the roundtable focuses on practical policy solutions, with each group contributing insights from its unique experiences and perspectives.

A 2020 report from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding reveals how this approach enables religious communities to transcend traditional political categories. American Muslims exemplify this complexity: They show the highest support among religious groups (65 percent) for partnerships with Black Lives Matter, for example, while also maintaining significant support (49 percent) for coalitions with political conservatives on religious liberty issues. This pattern demonstrates how communities can maintain distinctive identities while building strategic partnerships on specific issues.

The Multi-Faith Network for Climate Action further illustrates this sophisticated approach to coalition-building. When evangelical Christians, Orthodox Jews, and traditional Muslims come together around environmental stewardship, each group draws on its own theological resources—whether it’s the Christian concept of creation care, the Jewish principle of tikkun olam, or the Islamic concept of khalifah (stewardship). Rather than minimizing differences, the network leverages them to create a richer, more nuanced approach to environmental advocacy.

This evolving landscape must also account for America’s growing secular population. While religious groups remain politically significant, they must now engage with an increasingly visible group of religiously unaffiliated Americans, or “nones.” According to The Pew Research Center, most of these unaffiliated Americans still believe in God or a higher power, even while rejecting organized religion. This creates opportunities for new forms of collaboration that honor both religious and secular frameworks for ethical action.

The “nones” represent a diverse constituency with varying levels of civic engagement. Atheists and agnostics often demonstrate high levels of political and community involvement, making them natural partners in coalition-building efforts. Those who identify as “nothing in particular,” while less likely to participate in traditional civic activities, might be reached through new forms of engagement that speak to their spiritual interests without requiring religious affiliation.

As these collaborations evolve, religious literacy becomes increasingly vital for effective civic engagement. Building on the Pluralism Project’s framework, religious literacy today means understanding not just what different communities believe but how they actively engage with contemporary issues. The Religious Literacy Project at Harvard Divinity School exemplifies this approach through its teacher education programs, which help educators move beyond superficial “world religions” approaches to explore how religious communities shape public life. The Pluralism Project’s Case Study Initiative provides concrete examples of religious diversity in American civic life, helping students understand the complex ways religious identity shapes public engagement.

Media coverage of religion also plays a crucial role in building public understanding, though mainstream outlets often fall short in their portrayal of even basic religious practices and beliefs. Common issues include oversimplifying complex theological concepts, misidentifying religious symbols and customs, and relying on outdated stereotypes. For example, news outlets frequently conflate Sikhism with Islam, oversimplify Jewish denominations, and portray Christianity as exclusively Western or white when it has massive and growing populations across Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Style guides and reporting standards continue to evolve to promote more accurate and nuanced coverage of religious topics. Organizations like the Freedom Forum provide practical training for professionals navigating religious diversity in their work.

Looking forward, successful faith-based organizing will likely continue to evolve in sophisticated ways. Religious communities may increasingly function as bridges between different sectors of society, drawing on their unique positions to facilitate dialogue and collaboration across various divides. Their ability to maintain distinct identities while building strategic partnerships could offer valuable lessons for addressing other forms of social polarization.

The key to this future lies not in minimizing religious differences but in developing frameworks for meaningful collaboration that honor both distinctiveness and shared purpose. In this way, America’s increasing religious diversity might become not just a demographic reality but a genuine civic strength, demonstrating how active engagement across differences can serve the common good.

Jeffrey Bilbro: How to Discern Truth in Our Chaotic Digital Milieu

One theme of professor and author Jeffrey Bilbro’s writing is to help his readers make sense of the messy cultural nooks we find ourselves in, whether that be as students in the higher education system, consumers of news media, or users of technology. In an essay today on our website, Bilbro introduces some new ways of thinking about the morass of media and tech but reminding us of some old metaphors—for the telegraph:

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, greeted the advent of the telegraph by calling it “a net-work of nerves of iron wire” that will unite the nation. This metaphor caused him to make the confident claim that “the infallible Telegraph will contradict [newspapers’] falsehoods as fast as they can publish them … so that fraud and deception will be next to impossible.” Henry David Thoreau disagreed and instead saw the telegraph as conveying an unhealthy mental diet that would cause intellectual bloating. Thus he warned that “not only individuals, but States, [may thus acquire] a confirmed dyspepsia, which expresses itself, you can imagine by what sort of eloquence.” These contrasting metaphors imply quite different ways of using the same technology.

Media ecologist Neil Postman gestures to the power of metaphor when he crucially revises Marshall McLuhan’s famous adage, “The medium is the message.” Postman expands on this claim in Amusing Ourselves to Death, arguing that “the forms of our media ... are rather like metaphors, working by unobtrusive but powerful implication to enforce their special definitions of reality.” Thus the media through which a culture conducts its conversations powerfully shape that culture’s imagination.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

For the last few months, I’ve been hosting religion-centric conversations with writers, thinkers, and journalists—many of whom have contributed to the Dispatch Faith newsletter. We’ve been posting those conversations on the Dispatch YouTube page, but beginning this week, they’ll now live on our members-only podcast feed, known as The Skiff.

This week’s guest is Jeff Bilbro, who joined me to talk about his essay this week and his take on the state of higher education.

More Sunday Reads

- In Plough, German journalist Katja Hoyer writes about her experience as an atheist—when she realized having no religious faith wasn’t a norm for most people around the world—and why atheism is so pervasive in the former East Germany. “My whole worldview was clearly unusual. Other people prayed to God for guidance and support. I knew I was on my own. Believers shared the notion that there is some form of life after death rewarding the good and punishing the bad, which gives meaning to their lives here and now. I, on the other hand, often wondered even as a child what the point of life was if all you did is grow up, work, die, and be erased. When I lost relatives, friends, and pets, I knew I had lost them forever, while others held out for some form of reunion in another life or at least the idea that souls continued to exist somewhere.” And later, of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), she writes: “Once the GDR was set up, its policies continued to undermine the weakened foundations of Christianity in eastern Germany. Its measures toward the churches varied in intensity and methods over the years but were ultimately aimed at a phasing out of religion. Like the Soviet Union, East Germany followed Karl Marx’s doctrine that religion was ‘the opium of the masses,’ effectively a means to keep people in their allocated place in society and endure exploitation in exchange for salvation in the afterlife. But the regime was also keenly aware that it had inherited a society deeply rooted in Christian traditions and tired of conflict. So, an attempt to abolish the Protestant and Catholic churches outright was deemed too abrasive. The plan was rather to bind them into the state structures where they could be observed, controlled, and hollowed out over time.”

- Sean Rowe took over as presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church at quite a moment. The mainline denomination has been on the numerical decline for years, but his term begins just as Donald Trump was elected again to the White House and as Justin Welby resigned as the archbishop of Canterbury and leader of the global Anglican Communion. Rowe spoke with Religion News Service’s Yonat Shimron about the challenges he and his denomination now face: “I think it gets worse before it gets better. Some of it is related to the changing culture around us. Much of it is institutional. What people sometimes call organized religion has earned its reputation as being untrustworthy or partisan or judgmental or out of touch. Our lack of ability to be authentic and to allow the brand of Christianity to be almost entirely identified with the Christian right. That’s a piece of it. Also, our own failures holding ourselves accountable and our own inability to live up to our own values has cost us deeply. People are just saying, we don’t want to be part of this at this point,” he said in an interview. “However, it is a powerful tradition that we’re a part of. If we can reclaim that piece of our heritage, and open people up to the wideness and the richness of faith, that is compelling. But it’s not gonna look like it did. The truth of the matter is we don’t know what it will look like. We don’t know what structures we need. We have to experiment. I think this is a season of experimentation. It’s an exciting time, frankly, but it’s going to require us to be honest with ourselves in ways we haven’t been.”

A Good Word

Historian Austin Reid has spent the last few years collecting stories from Jewish communities in the small towns of his native Ohio and now adopted home state of New York. What he found in the past, he says, is encouragement for the present and future. “Small-town synagogues often function not just as religious institutions but as unique centers for education and community engagement. In Lancaster, the B’nai Israel synagogue opened its doors to various groups seeking to learn about Judaism. Its book fund ensured that, even after the synagogue’s closure, locals could continue to conveniently access resources devoted to Jewish culture and history. Eighty miles to the south, in Portsmouth, Ohio, the Jewish community was also engaged in interfaith efforts from its earliest days. When Beneh Abraham, the local synagogue, was consecrated in 1858, Christian residents of the town supported the construction, and the First Presbyterian Church choir even sang during the dedication. Such partnerships went both ways, with Jews contributing to the building funds for nearby churches.The local rabbi, Judah Wechsler, taught in both English and German. Wechsler’s leadership helped Beneh Abraham function as more than a religious space — it became a center for community engagement in Portsmouth. Portsmouth’s first synagogue, like many other historic religious structures in America, no longer stands today, but this early story from the town’s Jewish community reminds us of how intertwined religious groups in small towns can be.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.