At 7:33 a.m. on November 9, 2016, I published a short post at National Review called “May God bless President Trump.” It caused a few readers to do a double-take. “Wait. Weren’t you Never Trump?” “Didn’t you oppose him so much that you almost launched a third-party run against him?” Yes and yes, but as a Christian believer, I also knew two things. First, God was sovereign over the presidential election. Second, it was my obligation to pray for our president.

On the first point, the book of Romans contains a sweeping statement about the power of God over human affairs: “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.”

The second point is just as clear. As Paul told Timothy, “I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people—for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness.”

The belief that God placed Trump in the Oval Office should lead to the same conclusion about Joe Biden. The same fervent Christian prayers for Trump should now be on behalf of the president-elect.

Critically, when we pray for a president and his administration, we do not acquiesce in injustice. Our prayers may well represent one of our most effective forms of activism. After all, the book of Proverbs declares that “the king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord, like the rivers of water.”

But beyond our prayers, as Trump’s term ends, the church has its own opportunity for a new beginning—and perhaps a renewed commitment both to humility and to biblical justice. Deep commitments to partisanship have hindered the church’s witness to the world. And so, as a new administration begins, I’ve been thinking through three uncomfortable truths.

Knowing God’s power is not the same thing as knowing God’s purpose. As I read through social media, I’m quite frankly appalled at the intensity of the Christian anger and fear at Trump’s loss. This is the fruit not just of a constant media diet that so often valorizes Trump and demonizes his opponents, but also of a burning sense in many Christians’ minds that Trump had a distinct and decisive role to play in American culture, and this loss frustrates his presumed purpose.

Yet throughout scripture we see a pattern—God chooses one leader, then another. One leader falls, another rises. There are times when a leader’s own sin necessitates a different choice. There are also times when God gives the people the man they want, but not for the purpose they hope.

A number of Christians have tried to compare Trump to King David—a flawed man who became a righteous king. But that comparison has long puzzled me. David was deeply repentant for his profound sin. There is, by contrast, no evidence for Trump’s remorse. Is a better comparison perhaps King Saul?

Saul’s story is told in the Book of 1 Samuel, and I discussed it in one of my very first Sunday French Press essays:

Boiled down to its essence, after a period of chaos and turmoil (which included the ultimate insult of the Philistines seizing the Ark of the Covenant), the Israelites approach the prophet Samuel and demand a king. God directs Samuel to grant their request: “Obey the voice of the people in relation to all that they say to you. For it is not you they have rejected, but Me they have rejected from reigning over them.”

Samuel warns the Israelites of the oppressions to come, but he follows God’s command and anoints Saul as the first king of Israel. Saul won initial victories, but he also defied God’s commands, God rejected him as king, and then Samuel anointed Saul’s successor—not one of Saul’s sons, but rather the most famous king in the Old Testament, David. Throughout Old Testament history, the pattern is clear—the status of serving as God’s ordained king of Israel (even in the line of David himself) does not relieve that king of the obligation of following God’s commands or the people from suffering the consequences of the king’s failures.

It’s perilous to compare any president to a biblical figure, but the procession from Saul to David does teach us a few profound truths—God’s ways are not our ways, and when he chooses one man, he can and will choose another, and each man is under the same obligations to seek and do justice for the people he leads.

God’s purposes will not precisely match our partisan interests. It would take the boldest and most shameless of partisans to declare that his party’s platform exactly matches God’s desires for the United States of America. The result is that a truly honest Christian sometimes must oppose the ideas and policies of allied politicians and support the efforts of even sometimes-bitter opponents.

But partisanship makes this incredibly difficult. If you ever break ranks with your own team, it sparks deep anger. Any weakness, any crumbling in the partisan wall, is seen as giving aid and comfort to the enemy.

And this leads us to the third uncomfortable truth. Our partisan interests sometimes oppose God’s purpose. This is the most humbling of realities. In fact, given our profoundly limited knowledge and wisdom, even Christians acting in the utmost good faith can find themselves arguing fervently and sincerely for the wrong policy, the wrong idea, or the wrong person. I’ve done it. I can tell you chapter and verse of when I’ve done it.

But there’s a darker side to the partisan pull. Join a team, and there is immense pressure to effectively enter into what’s best described as a version of a lawyer/client relationship. Once you have your “client” (your candidate), then at best you’ll often remain silent when your client is wrong. A worse response not only ignores your side’s flaws, it constantly redirects attention to sins on the other side.

The worst tactic of all is to defy the truth of Isaiah 5:20—“Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter.” How many times have we seen this grave error during Trump’s term, when civility has been despised and kindness scorned as weakness, as inadequate to the needs of the moment?

So here’s my simple prayer for President Biden: May God bless him and grant him the wisdom to know what’s just, the courage to do what’s just, and the stamina to withstand the rigors of the most difficult job in the world. May his virtuous plans prevail and may his unrighteous efforts fail. And may God protect him from all harm.

But there’s a prayer for believers as well. May we also have the wisdom to know what’s just and the courage to do what’s just—including supporting this president when he’s right and opposing him when we sincerely believe he’s wrong, regardless of the alleged partisan imperatives in play. May our own virtuous plans prevail and our own unrighteous efforts fail. And may we never put our trust in presidents, but instead in the God who sits upon an eternal throne.

One more thing …

Yesterday I tweeted the thought below, and a number of people responded immediately with a litany of Joe Biden’s faults and wrongs. Here’s the tweet:

I think that the critical responses are sad and sometimes cruel. One does not have to agree with Biden’s policies—and one can even still feel aggrieved at Biden’s sins—but it strikes me as terribly small not to acknowledge the immensity of the moment, the depth of his suffering, and the actual virtues he demonstrated in the campaign.

Joe Biden said some tough things about Mitt Romney in 2012, yet Mitt was right to say this:

No, Biden isn’t perfect. We disagree on many things. But since when do we require perfection or agreement to appreciate a good moment in a man’s life, especially when he has endured such terrible grief, including the recent death of his beloved son? Moreover, messages like Biden’s below are gracious and meaningful, and while we know there are political fights to come, these are the gestures (like Mitt’s above) that help sustain our republic:

One last thing …

Lots of readers really appreciated the Zach Williams song last week. You know what’s better than Zach Williams? Zach Williams and Dolly Parton. I love this song on its own merits, but every song is better when Dolly sings:

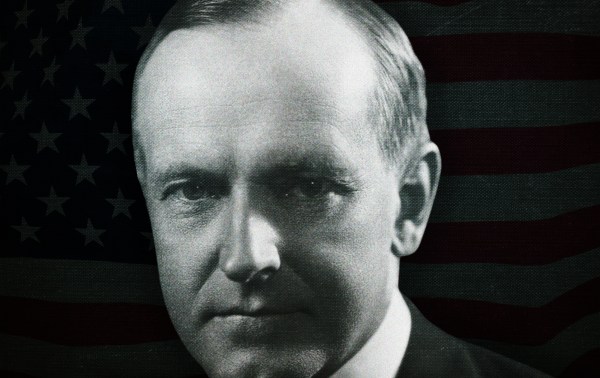

Photo by Andrew Harnik-Pool/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.