Longtime readers of this newsletter may remember an essay from all the way back in March, at the onset of the COVID pandemic. It was called “Coronavirus and the Fog of War,” and in it I cautioned against the temptation to quickly form definitive opinions about fast-moving, complex and contentious events. In stressful situations, first reports are often flatly wrong, some reports are so incomplete as to be misleading, and bad faith actors often fill in the information gaps with hot takes and definitive declarations.

In those circumstances, conventional wisdom can harden into virtual concrete days (or even hours) before we learn anything close to the true story of any given event. And thanks to our transient attention spans, the true stories sometimes get a fraction of the attention of early, false narratives.

One of the worst examples of the phenomenon is so well-known in conservative circles that it’s simply condensed to a single school name—“Covington Catholic.” A highly misleading slice of a much larger video rocketed across the internet at lightning speed, resulting in a deluge of fundamentally false news stories. An avalanche of hatred buried a school, a small Catholic community, and the young boys at the center of the story.

(If you’ve forgotten the details of that dreadful day, I’d urge you to read Caitlin Flanagan’s powerful indictment of the media in The Atlantic. There was something deeply chilling about the hysterical rage unleashed on those kids.)

Fortunately for the Covington Catholic students, the backlash against the early reporting was so fierce and so sustained that they’ve largely been able to recover their reputations. The offending media outlets ultimately suffered the consequences of their own misconduct.

We should realize, however, the extent to which our ideas about complex and important stories are often shaped in the fog of political war, when misleading stories are most apt to spread. Yet unlike the aftermath of Covington Catholic, these stories aren’t followed by the same level of prominent correction. The misleading story lingers, especially when that story fits an ever-hardening existing narrative. Sometimes those narratives create momentum for misguided change.

Let’s take a closer look at two recent, deeply contentious news events: Amazon Web Service’s decision to terminate its web hosting agreement with the right-wing social media site Parler and Robinhood’s decision to stop certain trading activity during the Reddit revolt over GameStop.

Millions on the right viewed the Parler cancellation as all the evidence we need that Big Tech is out of control. You mean Trump supporters can’t even start their own social media network without progressive Big Tech’s permission? The market is broken. Cancel culture is out of control.

But what if there’s a different story? What if Parler had been warned about violent content and proved unable to respond effectively to known issues on the site? What if Parler breached its contract with Amazon? Does that change the analysis?

As many readers might know, a federal judge recently denied Parler’s request for an injunction that would force Amazon to resume hosting Parler. The judge’s opinion received little attention on the right, but the factual description of the case and Parler’s contract with AWS should. Here are two key segments:

In recent months, Parler’s popularity has grown rapidly, and around the time of the 2020 presidential election, according to Parler, millions of users were abandoning Twitter and migrating to the Parler platform. During this same time period, AWS claims that it received reports that Parler was failing to moderate posts that encouraged and incited violence, in violation of the terms of the [Customer Services Agreement] and AWS’s Acceptable Use Policy (“AUP”). The AUP proscribes, among other things, “illegal, harmful, or offensive” use or content, defined as content “that is defamatory, obscene, abusive, invasive of privacy, or otherwise objectionable.” AWS claims that in recent weeks, it repeatedly communicated with Parler its concerns about third-party content that violated the terms of the CSA and AUP, and that Parler failed to respond to those concerns in a timely or adequate manner. (Citations omitted.)

In plain English, this means that Parler was breaching its agreement with Amazon and knew it was in breach. What is Parler’s defense? Amazon should have given it more time to fix the problems. But that’s not what the contract mandated. Stick with me:

Parler has not denied that content posted on its platform violated the terms of the CSA and the AUP; it claims only that AWS failed to provide notice to Parler that Parler was in breach, and to give Parler 30 days to cure, as Parler claims is required per Section 7.2(b)(i). However, Parler fails to acknowledge, let alone dispute, that Section 7.2(b)(ii)—the provision immediately following—authorizes AWS to terminate the Agreement “immediately upon notice” and without providing any opportunity to cure “if [AWS has] the right to suspend under Section 6.” And Section 6 provides, in turn, that AWS may “suspend [Parler’s or its] End User’s right to access or use any portion or all of the Service Offerings immediately upon notice” for a number of reasons, including if AWS determines that Parler is “in breach of this Agreement.” In short, the CSA gives AWS the right either to suspend or to terminate, immediately upon notice, in the event Parler is in breach.

I’m sorry, but it’s not “cancel culture” when a company terminates a contract with a party that’s in breach, and the breaching party doesn’t even deny it violated the contract. And this was no benign violation. Parler was flooded with violent content, including content that helped precipitate the deadly attack on the Capitol.

But what about Robinhood? Didn’t it squelch a grassroots rebellion against short sellers and greedy hedge fund plutocrats? That was the claim, anyway, when it restricted trading on GameStop in the midst of the GameStop buying frenzy. Tech critics on the right and left were furious:

Political and social-media opportunists jumped in. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez deemed GameStop trading restrictions “unacceptable” and demanded an investigation. Rep. Rashida Tlaib of the Financial Services Committee accused Robinhood of “stealing millions of dollars from their users.” Sen. Ted Cruz took to Twitter to “fully agree” with AOC: “Let the people trade.” Elon Musk “absolutely” agreed that Robinhood should be investigated, and called for short selling to be banned as “a scam.” Dave Portnoy, Barstool Sports founder and frozen-pizza reviewer, said to Robinhood executives: “You deserve to be behind bars.”

So Big Tech was at it again, right? Not so fast. Here’s Derek Thompson, writing in The Atlantic:

But what really happened had little to do with manipulation or hedge funds. Robinhood just ran out of money. With the sudden explosion in price and volatility for stocks including GameStop and AMC, the brokerage had to fork over several billion dollars to a clearinghouse of stocks, the National Securities Clearing Corporation. But Robinhood didn’t have the cash. So the company restricted trades on high-flying “meme stocks” for a few hours, while it went out to raise several billion dollars from investors.

In addition, Robinhood had to act in part because (interestingly enough) it’s subject to more regulatory oversight than social media companies. As David Battan, a former senior counsel in the enforcement division of the Security and Exchange Commission explained, “Under federal anti-money-laundering regulations, [brokerage] firms must conduct ‘reasonable surveillance’ for client fraud or criminality.” They can be subject to “eye-watering fines” for their clients’ “manipulative activity.”

Once again, a simple story became much more complicated. But that hasn’t stopped some powerful voices from continuing to advance a false narrative. Writing in First Things, Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley falsely described Robinhood’s trading pause as “Big Tech” engaging in “content moderation.” No, really:

So when GameStop traders decided to call Wall Street’s bluff—when the elites’ stock options house of cards started tumbling down—Big Tech did what it does best: It shut down their Discord server and closed off the Robinhood purchases. This wasn’t market manipulation, of course. It was just content moderation.

I share these stories not because I believe that American tech companies always make the right calls. Hardly. They possess immense power, and they sometimes don’t exercise it responsibly. For example, I criticized Twitter for squelching the Hunter Biden laptop story in the run-up to the presidential election. But a Big Tech persecution complex is locking into the right-wing mind, and it’s not only leading to a misleading picture of widespread conservative censorship, it’s also spawning unconstitutional legislative initiatives.

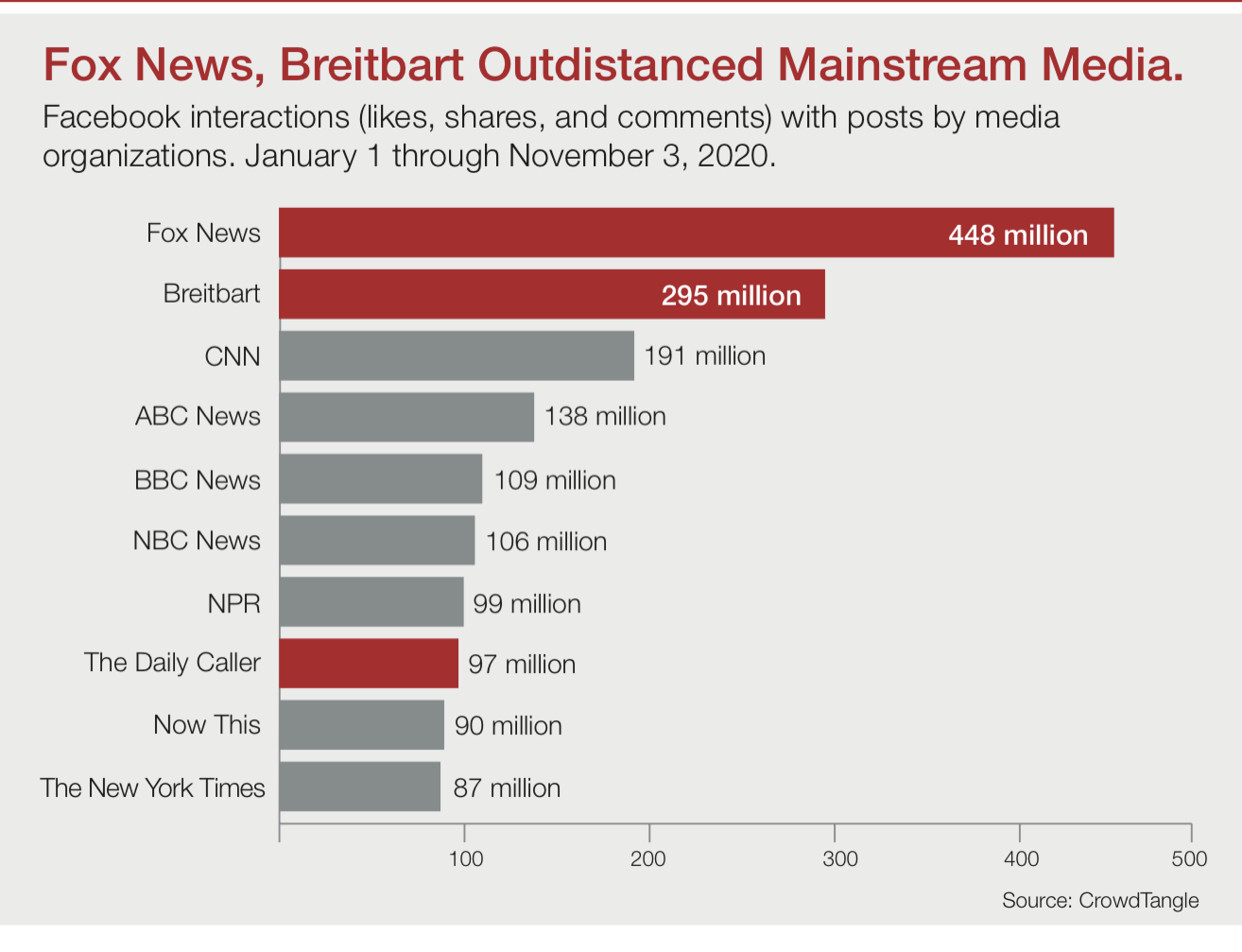

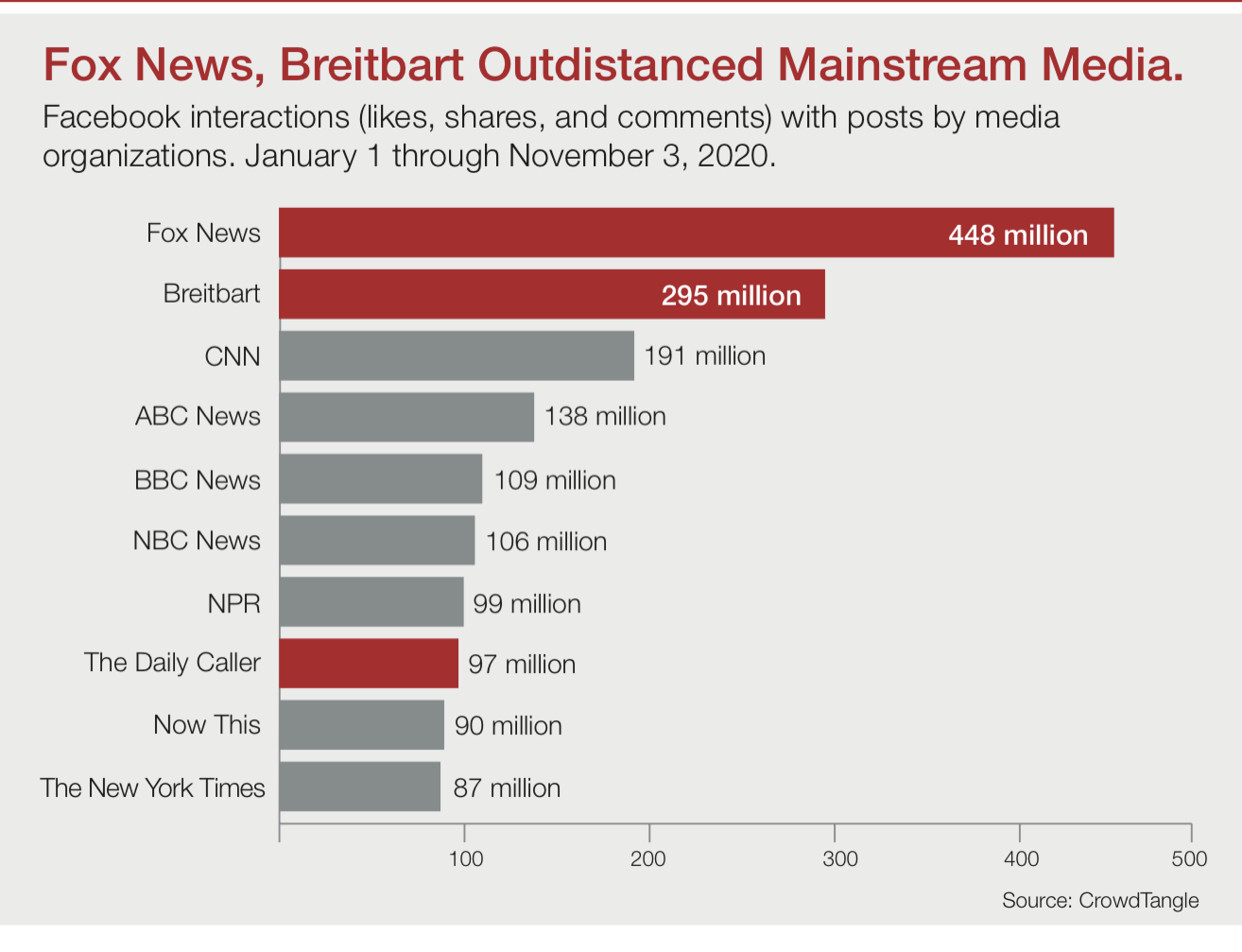

Earlier this week, Paul Barrett and J. Grant Sims released a study of social media censorship that found conservatives as a whole do quite well in Big Tech. In fact, there are key right-wing outlets that far outperform left-wing competitors. These charts are instructive:

And:

I don’t endorse all the study’s conclusions. As I noted above, individual moderation decisions are open to legitimate critique, and social media companies are often too opaque with their data and their decision-making processes. However, the bottom line reality is far less dire that right-wing tech critics claim. Conservatives do not have problems accessing social media, and they often outperform progressives on progressive-owned platforms.

Yet fury at Big Tech is leading to misguided measures like this, from the State of Florida:

Fining companies unless they host political speech against their will raises a host of constitutional questions. It’s a misguided solution in search of a problem. I know that Twitter and Facebook knocked Donald Trump off their platforms (a good decision, in my view), but are we really prepared to argue that candidates should be functionally immune from terms of service and that they should enjoy an extraordinarily privileged right of access to public spaces regardless of their speech or conduct?

In the fog of political war, false narratives are taking hold. False narratives contribute to needless outrage. Needless outrage creates bad policy. For all our sakes, it’s time for journalists and politicians to pause, to let the fog clear, and to think long and hard before drafting laws that create “cures” that are worse than the problem or may target problems that do not truly exist.

One last thing …

In our most recent Advisory Opinions podcast, Sarah and I had a spirited conversation about fonts. Yes, fonts. Trust me, it was fun. Or at least my lawyer-readers will think it’s fun. Anyway, that brought back to my mind one of my all-time favorite nerdy SNL skits. It’s just called “Papyrus.” Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.