Late last week I was talking with a good friend, and he asked an excellent question. “Are these times really as hard as they seem? Or have we lost historical perspective? Does every generation face the challenges we face?” It’s a great question, and it immediately brought to my mind an offhand comment the New York Times’s Michelle Goldberg made in a podcast last spring.

I’ve referred to it before, but what she said was something like this. 2020 started out like 1974 (impeachment), became 1918 (pandemic), which led to 1929 (a stock market crash), and then transformed into 1968 (with massive urban unrest). Since that podcast, things only got worse. We moved into 1876 (a viciously disputed election), followed it up with another 1974 (second impeachment), and then experienced 1975 (a lost war and a panicked evacuation).

I haven’t even mentioned January 6, which was the closest we’ve come to 1861 in my lifetime.

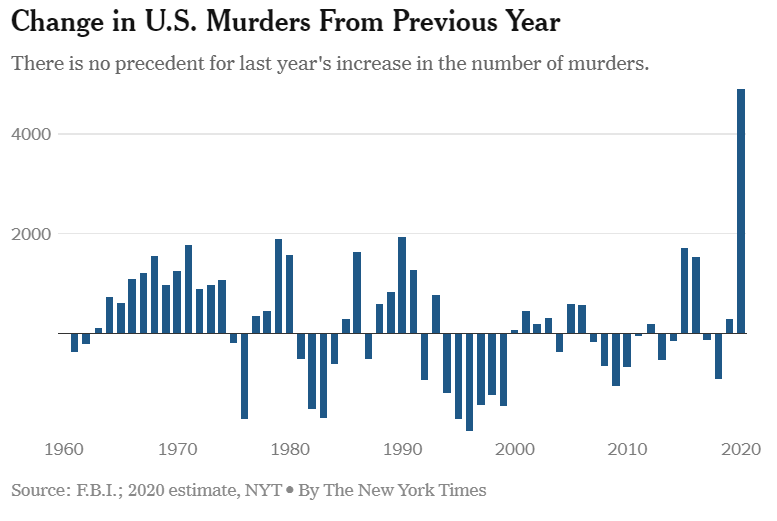

At the risk of further deepening the gloom, I’m going to add another date to the mix. Tomorrow the FBI is expected to release its Uniform Crime Report (UCR) for 2020. On Wednesday the New York Times published a preview. The 2020 murder rate is expected to have risen by a stunning 29 percent, the largest increase since 1968 (there’s that date again) and the largest one-year increase since the FBI has been keeping statistics.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Look at the scale on this chart:

None of this is really news. Media outlets have been tracking crime increases for months. Still, there’s something especially grim when the FBI makes it all “official” with the release of the UCR.

By now some readers might be a bit confused. Isn’t the Sunday essay the “faith essay”? Why are we talking about murder rates? The answer is pretty simple—if people of faith are to be concerned about justice (and they are!), then justice is rarely more immediate and important than when confronting both the scourge of crime and the tragedy of excess enforcement and mass incarceration.

Compounding the challenge, the class of Americans most engaged in politics (disproportionately white, educated, and well-off) are often the least impacted by crime. They’re less likely to feel either the effects of crime or the effects of stepped-up law enforcement. Thus we often find ourselves talking about communities rather than with communities and making mistakes accordingly.

Here is my fundamental concern. If we fail to fully understand what justice is—and to distinguish between justice and vengeance—then fears of crime and fears of law enforcement may cause us to amplify and repeat the profound injustices of the recent past.

It’s helpful to discern what justice is in part by describing what justice is not. Let’s start with three key concepts. Impunity is unjust. Vengeance is unjust. And justice, not vengeance, leads to deterrence.

Impunity is unjust. There are two forms of impunity I’m concerned about—criminals committing violent crime with impunity and law enforcement officers violating civil rights with impunity. Crime is oppressive, and state inaction that permits it to flourish contributes to social decay.

Last month, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf wrote an important essay arguing that “under-policing is a form of oppression too.” Combine criminal activity with absent or ineffective police, and you have a formula not just for death and destruction but for pervasive fear and economic decline.

In one of his most telling paragraphs, Friedersdorf noted how easy it is get away with murder in the United States of America, especially if the victim is black:

The Murder Accountability Project, a nonprofit watchdog group that tracks unsolved murders, found in 2019 that “declining homicide clearance rates for African-American victims accounted for all of the nation’s alarming decline in law enforcement’s ability to clear murders through the arrest of criminal offenders.” In Chicago, the public-radio station WBEZ’s analysis of 19 months of murder-investigation records showed that “when the victim was white, 47% of the cases were solved … For Hispanics, the rate was about 33%. When the victim was African American, it was less than 22%.” Another study in Indianapolis found the same kind of disparities.

These are stunning numbers. The failure to solve murders and hold murderers accountable not only breeds lawlessness, it creates a profound, independent moral injury. One of the first sins recorded in scripture is Cain’s murder of Abel, an act that caused God to say to Cain, “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground.”

And it’s not just murder that creates the cry for justice. Days ago we watched as America’s elite gymnasts cried out to Congress for justice in response to years of abuse and neglect—abuse at the hands of their team doctor, Larry Nassar, and neglect from the establishment, from USA Gymnastics to the FBI itself.

But the recognition of the awful consequence of crime brings me to the second concern—a culture of impunity is unjust if it comes through police absence or through police excess. And historically fear of crime has caused Americans to empower police beyond the rightful bounds of the law.

Previous crime waves brought forth the widespread use of militarized tactics (such as no-knock raids) and permissive doctrines (such as qualified immunity and other doctrines that protect police officers and police departments from liability even when they violate the civil rights of citizens) that often permit public officials to answer brutality and lawlessness with brutality and lawlessness all their own.

Extremists on competing sides constantly create false choices. We don’t have to choose between the diminished police forces desired by those adjacent to the defund the police movement and the militarized police aggression that has created its own injustices.

Better trained, more accountable police forces can help provide an answer to both problems of impunity. Last summer, when riots were sweeping American cities and the Defund the Police movement surged, I argued that we shouldn’t solve the problems of policing with fewer officers and diminished resources, but with better officers and improved tactics. Pay police more, train them better, and, crucially, expect more. Increased professionalism and increased accountability go hand-in-hand with increased competence and effectiveness.

Vengeance is unjust. Proportionality is an absolutely indispensable element of justice. The punishment should fit, not exceed, the crime. Even the much-maligned concept of lex talionis (think of the Old Testament concept of an “eye-for-an-eye”) represented a limitation on the human temptation to exact overwhelming retribution—vengeance—on your enemies.

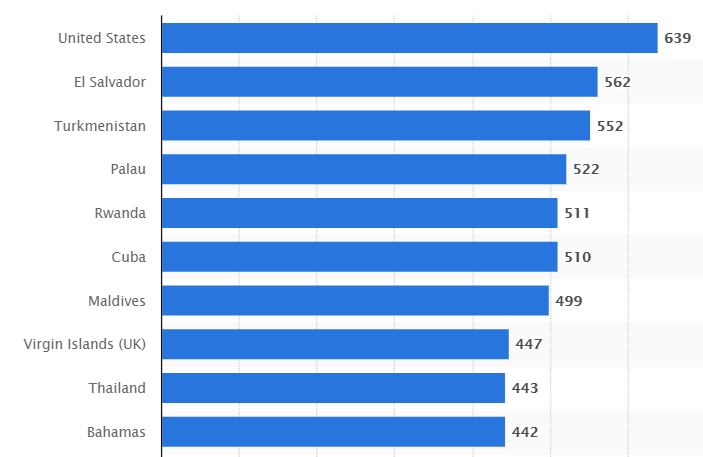

It is here where the American response to crime can be most alarming. When we look at the sheer scale of American incarceration and the sheer scale of American executions, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that in many ways we’ve created a vengeance system as much as a justice system. Indeed, the scope of American incarceration is difficult to comprehend. Courtesy of Statista, here are the top ten countries with the largest number of prisoners, per 100,000 people.

Let’s put aside for a moment the fact that I don’t trust, say, North Korea’s statistics. It remains true that we far, far outpace any other peer nation in the world with our sheer numbers of prisoners.

What’s another example of vengeance? Consider “three strikes” laws, which can hit habitual offenders with a life sentence after their third felony, even if that felony wouldn’t merit anything close to a similar sentence on its own. The hammer still falls, and the resulting injustices can sometimes boggle the mind. In 1980, for example, the Supreme Court upheld a lifetime prison sentence for a nonviolent felon whose three offenses involved a total of roughly $229.

And we should not think that such incredible punishments and incredible rates of imprisonment are necessary for public safety. The precipitous crime declines of the 1990s and early 2000s are among the most-studied and complex phenomena in public life, and to say that “getting tough” made the difference is to dramatically oversimplify the debate.

In fact, the smartest conclusions have determined that rapid increases in incarceration are not in fact principally or even significantly responsible for declines in American crime, and they have long passed the point of diminishing marginal returns. A 2012 Brennan Center for Justice paper found that “increased incarceration has been declining in its effectiveness as a crime control tactic for more than 30 years. Its effect on crime rates since 1990 has been limited, and has been non-existent since 2000.”

I don’t want to oversell this point. It’s not that increased incarceration has no effect on American crime, just that that effect has been increasingly marginal. At the same time, however, it has an immense impact on the millions of Americans who are caught up in the system itself, either as prisoners or as their children, spouses, or parents. The effects on family formation and lifetime earning potential are catastrophic, for example, and can lead to enduring cycles of poverty and inequality.

And that’s without even addressing the vast racial disparities in both incarceration and sentencing. There is no question that America has progressed past the worst days of an thoroughly and explicitly racialized justice system, but it is still true that not only are black and Hispanic men far more likely to be imprisoned than white men, there is a disturbing amount of evidence that they’re often charged with more severe crimes than similarly situated whites.

Justice, not vengeance, leads to deterrence. This last point is crucial. There are many millions of Americans who look aghast at American crime and say, I’m not interested in vengeance, but I do want deterrence. Life in prison, for example, doesn’t just lock up the offender and keep him from offending again, it also presents an object lesson that crime doesn’t pay. In other words, it’s not that harsh punishments necessarily fit the crime, it’s that harsh punishments prevent crime. Criminals are “scared straight.”

But the best evidence, summed up in this very handy and short National Institute for Justice publication is that neither the death penalty nor increasingly severe prison sentences deter crime. Criminals often don’t know the sanctions attached to crimes, and lengthy prison sentences don’t “chasten” prisoners and can in fact increase recidivism. Prison can often act like a crime academy, where prisoners make criminal contacts and learn criminal tactics.

So what does work? It turns out that increasing the certainty of punishment rather than the severity of punishment has a far greater deterrent effect. In other words, remove the sense of impunity and replace it with a probability of justice, and deterrence rises. Critically, this deterrence can often be accomplished merely by police presence. As the National Institute for Justice states, “Strategies that use the police as ‘sentinels,’ such as hot spots policing, are particularly effective. A criminal’s behavior is more likely to be influenced by seeing a police officer with handcuffs and a radio than by a new law increasing penalties.”

I think we can all agree that a police presence is infinitely preferable to prison as a guarantor of public safety—assuming, of course, the police officer is well-trained and accountable to the rule of law.

I’ll be honest, I’ve got a bit of a personal connection to this conversation, a connection that I’d never had before. In 2019 my wife was blessed to work with Alice Johnson on her autobiography, After Life. Johnson, readers may remember, was a first-time drug offender who was sentenced to life in prison at the height of the war on drugs. Donald Trump granted her clemency (and later pardoned her) after Kim Kardashian pleaded her case in the White House. It was one of Trump’s best moments in office.

Alice stayed at our house for a short time while she finished her book, and our conversations helped teach me that there is a tremendous need for an interfaith, cross-partisan coalition of Americans who can see that crime imposes real costs on communities, while also understanding that vengeance and mass incarceration is toxic to the culture and soul of a nation.

A coalition has to stand in the gap between “defund the police” and “lock them up,” between criminal rule and police impunity, and articulate a vision of justice that preserves public order, human dignity, and individual liberty.

And in fact, there are Americans who have been doing just that. They’ve set aside partisanship to create surprising coalitions. Trump was elected after one of the toughest law-and-order campaigns in modern memory, yet he also signed the First Step Act. The federal prison population declined on his watch. Texas, despite its long reputation for harsh law enforcement, has been a national leader in prison reform.

Yet now we face a challenge. In a single extraordinary year, the terrible scourge of violent crime came roaring back, oppressing and terrifying the citizens of countless communities across the nation. It’s a challenge we can face, using the knowledge gained from bitter experience, combined with the courage and good will of citizens who seek justice, but we cannot—we must not—allow fear to drive us to repeat and compound the national injustices of the very recent past.

One last thing …

There’s not much to say to introduce this song. It’s just great. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.