It’s been years since I’ve seen Americans so united by grief and fury. The grief is for the 19 children and 2 teachers murdered at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. The fury is against the police officers who waited—minute after agonizing minute—while the killer hid behind a locked classroom door.

The facts are almost too painful to recount. According to the latest timelines, at 11:33 a.m. on Tuesday, May 24, the Uvalde mass shooter (I’ve adopted a practice of refusing to name spree killers) entered the school and began shooting into classroom 111 or 112. Two minutes later, at 11:35 a.m., three Uvalde officers arrived at the closed classroom door. Two were lightly wounded by gunfire from the shooter. Four more officers arrived.

Let’s pause right here. According to Uvalde police training documents obtained by Mike Baker and Dana Goldstein at the New York Times, this moment should have led to an immediate, sustained, and sacrificial engagement with the shooter. Police, including Uvalde police, are taught to engage a police shooter and not to stop, even if it means taking casualties. Here are some key quotes:

First responders to the active shooter scene will usually be required to place themselves in harm’s way and display uncommon acts of courage to save the innocent.

More:

As first responders we must recognize that innocent life must be defended. A first responder unwilling to place the lives of the innocent above their own safety should consider another career field.

When a man or woman puts on a uniform and straps on a gun—whether they’re a police officer or a soldier—they should be making a profound declaration. They’re willing to die to protect their community and their nation. They don’t want to die, of course. But they’re willing to pay the “last full measure of devotion” if that moment arrives.

That’s why we respect men and women in uniform. In some cultures, the uniform is a symbol of authority, not sacrifice, and those who wear uniforms are feared far more than they’re respected. In our culture, we thank soldiers for their service and “back the blue” because, in theory, they’ve placed our lives above their own.

And so, at 11:35 a.m. the seven officers present had but one choice—fight to the death to protect and save as many children as they could. They were to emerge from that school with their shield or on it. There was no other moral choice.

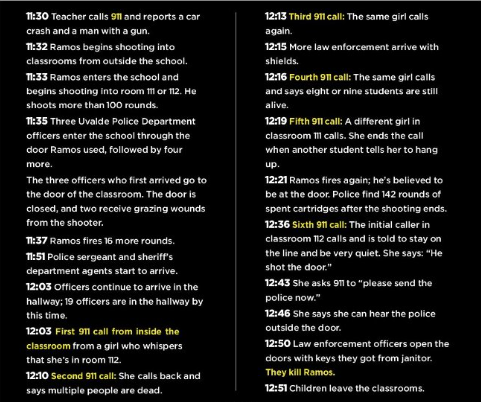

But they waited. And waited. And waited. Two different girls called 911, begging for help. Their classmates were dead and dying all around them. They were in mortal danger. The first call came at 12:03. That same girl called back at 12:10, at 12:13, and 12:16. A different girl called at 12:19. The final call came at 12:36.

At this same time, families were rushing to the school. Police blocked them from trying to reach their children. The result was ultimate anguish. The videos are hard to watch.

At 12:50 p.m. the police finally opened the door with a key, charged into the room, and killed the shooter. That was one hour and 15 minutes after the first police contact in the school. This timeline from the Dallas Morning News tells the story with devastating simplicity:

Police initially attempted to explain this delay by saying they believed “there were no kids at risk,” but they now acknowledge they made the “wrong decision.”

This horrific police failure occurred four years after a similar police failure in Parkland, Florida. Sheriff’s deputy Scot Peterson notoriously stayed outside as a killer rampaged through the halls and classrooms of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, but “seven other sheriff’s deputies who raced to the school and heard gunshots also stayed outside the building.”

We can and should investigate failures in command and control. We should re-examine police training. But we also need to acknowledge that what happened on the ground was that men were afraid, and in that moment, their courage failed.

Had the first seven officers pressed in, even as one or more of them fell, we’d still mourn the children who died, and we’d still be torn apart by debates over guns, but in our cultural crisis we’d know a degree of cultural comfort. Great courage would have confronted great evil, and we’d be reminded again about what the uniform is supposed to mean.

As I wrote after the Parkland school massacre, cultivating courage is a complex and difficult task. Some cultures are better at it than others, and absolutely no sane nation or institution relies on the inherent goodness or bravery of their police or military to sustain their civilization.

It’s a simple fact that when men or women face mortal danger, every single molecule in their bodies screams at them to seek shelter and safety. It takes immense effort to overcome the desire for self-preservation. Training can help, but it isn’t enough. What’s required is a fundamental, deeply embedded ethos—a core understanding that love may require their lives.

Parents possess this ethos almost as a matter of instinct. Intelligent armies construct this ethos by building bonds between brothers-in-arms. Dying for a nation is an abstract concept when the bullets fly. Risking everything for the brother beside you? That makes immediate, visceral sense. I won’t say that everyone I served with in Iraq was brave, but I cannot imagine my brothers failing me in a moment of crisis, and I pray that I would never fail them.

At the root of a failure of courage is often a failure of love. C.S. Lewis wrote that courage is “not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point.” Jesus said, “No one has greater love than this: to lay down his life for his friends.” What we witnessed from the police in Uvalde was the triumph of self-love over love of others, including of the young kids bleeding in that room.

At the testing point, the officers were confronted with a question, “Whom do you love?”

“I love me,” they responded, and they stood down.

That declaration, “I love me,” is endemic in our nation, and it’s not just endemic when lives are on the line. It’s dreadful to read the comprehensive report on the Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee’s response to abuse allegations and understand exactly how much of the misconduct was driven by the desire for self-preservation. Preserve the assets of the ministry. Preserve the power of the leaders.

As my wife Nancy continued her tireless investigation of Kanakuk Kamp in Missouri, writing most recently in USA Today about decades of abuse involving multiple predators, you see the same desires in play. Protect the leaders. Protect the camp. Justice is secondary. Accountability is a threat.

At the testing point, these institutions were confronted with a question, “Whom do you love?”

“We love us,” they responded, and they covered up abuse.

The cross utterly rebukes this ethos. Jesus could not be more clear. “If anyone wants to follow after me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me.” And with this command comes a warning and a promise, “For whoever wants to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life because of me will find it.”

It’s a terrible irony the police failure in Uvalde occurred less than one week before Memorial Day. I hope that we can pause for just a moment on Monday and remember those who did not stand down. I’m remembering men like my friend Mike Medders, who died directly confronting a suicide bomber in Iraq. I’m remembering my friend Torre Mallard, who always led from the front—until an IED claimed his life and the life of three other brothers in a Humvee in 2008.

Our nation still produces such men and women, and one way to continue to cultivate courage is to remember them, honor them, and teach the next generation to emulate them. Yes, condemn cowardice, but also celebrate valor. Remind our nation that its heroes made a better choice.

At the testing point, they were confronted with a question, “Whom do you love?”

“We love you,” they responded, and they went in.

Our nation is sustained by sacrifice. It is strained and stained by cowardice. May the shame of Uvalde shake us from our national malaise. May the memory of our fallen call us back to our highest ideals. And may God have mercy on us all.

One more thing …

This week Curtis and I talked to my wife Nancy about her two years-long Kanakuk investigation. She walks us through the story from the first tip from former Fox anchor Gretchen Carlson to the thousands of conversations with hundreds of witnesses. Warning: it’s a hard, emotional conversation, but it’s very much worth your time.

One last thing …

At the end of a week that once again shakes our faith in people and the institutions we build, I’m ending with this beautiful song, which reminds us where we place our hope—in life and death:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.