Donald Trump’s favorite poem is arguably “The Snake.” Trump likes to read it at rallies.

“The Snake” isn’t a poem, it’s really a song, first written and recorded by Oscar Brown but made (relatively) famous by Al Wilson. The story in the song is basically a variant of Aesop’s tale of the scorpion and the frog. A woman finds a half-frozen snake. She takes it in and nurses it back to health. Spoiler alert, the snake bites her. Here’s a truncated excerpt:

Now she hurried home from work that night as soon as she arrived.

She found that pretty snake she’d taken in had been revived.

“Take me in, oh tender woman ,

“Take me in, for heaven’s sake,

“Take me in oh tender woman,” sighed the snake.

Now she clutched him to her bosom, “You’re so beautiful,” she cried.

“But if I hadn’t brought you in by now you might have died.”

Now she stroked his pretty skin and then she kissed and held him tight .

But instead of saying thanks, that snake gave her a vicious bite.

…“I saved you,” cried that woman.

“And you’ve bit me even, why?

“You know your bite is poisonous and now I’m going to die.”

“Oh shut up, silly woman,” said the reptile with a grin,

“You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in.”

Trump uses the poem to denounce immigration and, by extension, immigrants. That’s not my interpretation. Trump helpfully tells audiences: “Think of it in terms of immigration.”

Now, I think Trump’s usage of the poem is gross. But that’s not important right now.

“The Snake” came to mind yesterday with the news that Trump was unsatisfied with his previous attempts to kill Project 2025, a product of the Heritage Foundation, which bills it as an effort to “pave the way for an effective conservative administration.”

As our own fact check recounted, a lot of the caterwauling about Project 2025 is silly hysteria. It doesn’t call for a complete ban on abortion, contraception, no-fault divorce, or worker protections, just to name a few falsehoods pushed by Democrats. It does call for various longstanding conservative things, some of which I have no major problems with, like getting rid of the Department of Education and increasing oil and gas drilling in the Arctic.

What Project 2025 is—or was—was an attempt by Trump’s biggest supporters—many of them alumni of the Trump administration—to put meat on the bones of what Trumpism actually is.

The problem for the Trump campaign is that it has been working diligently on a Trump makeover. And, fairly or not, Project 2025 made Trump seem like he actually believes some of the things his biggest fans think he believes.

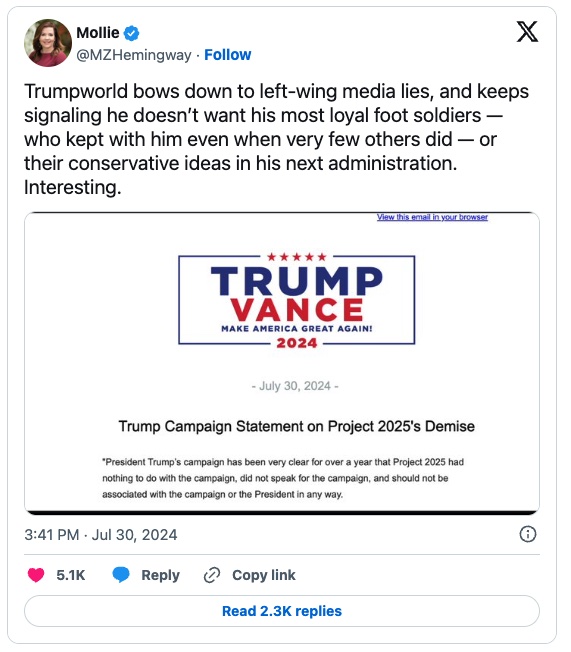

I don’t often agree with Mollie Hemingway these days, but she was basically right when she castigated Trumpworld.

Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation, is as loyal a foot soldier of Trump as you can get, short of wearing a suicide vest and charging into Alvin Bragg’s office. So is Paul Dans, a former Trump administration official, and—until yesterday —the director of Project 2025 and a Heritage fellow. He resigned from both positions under pressure from the Trump campaign. Rumors that he’s looking for a new think tank billet as senior scholar of Bus-Underside Studies could not be confirmed. Roberts declared that Project 2025 will endure, but will “conclude its policy drafting” at the conclusion of the Democratic National Convention. In short, he’s giving the Trump campaign a talking point about it closing while not actually disappearing.

Now, I actually think the idea behind Project 2025 was not stupid. Preparing a policy agenda and identifying qualified personnel for a new Trump administration—or any president’s administration—is a good idea. We can debate the specific merits of the proposed personnel or the policies, but such a project is perfectly in line with the Heritage Foundation’s historic role on the right, going back to the Reagan administration; they’ve published a “Mandate for Leadership” for every election cycle since 1981. It’s also, various legal and institutional caveats aside, what many think tanks do.

What was stupid—hilariously, incandescently, gloriously stupid—was the way the Heritage Foundation went about it. The organization could have worked quietly behind the scenes, developing ideas and staffing prospects. And then, when—or if—Trump won, it could have been ready to help with the transition.

But that is not how politics works in Trumpworld.

Unitary Trumpism.

Let me offer an analogy. As many have learned with the recent debates over presidential immunity, the executive branch’s authority resides in, and flows from, a single person. As a legal matter, the attorney general, the secretary of state, et al. have no authority, no power, to do anything, that isn’t derived from the president’s authority, because the president, under our Constitution, is the executive branch. That’s why it’s a legitimate question whether the Justice Department can prosecute the president because, in legal terms, the Justice Department is the president.

Trump’s political authority works in a similar fashion. If you are in good standing with Trump, you are in good standing with the party. If he hates you, declares you to be disloyal, or even inconvenient to him, you lose your political power. Obviously, this is somewhat overstated. I’m talking about the difference between formal and informal power. If you hold elected office, you still have some power and agency, but you’re going to lose a lot of your influence. And woe betide a Republican who tries to run in a primary when Trump unpersons you.

Now, if Trump loves you, you can say or do anything without paying much of a price—see Matt Gaetz, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, and the other Republican gargoyles. If he hates you, best to consult your financial planner about how you want to enjoy your retirement or your new chapter in the private sector.

The analogy extends further than that. When you’re in the executive branch, you have whatever authority you derive from the position and from the president’s support. But when you leave government, you leave your government badge and your power behind. That’s how republicanism works. Similarly, when you leave Trump’s good graces, you can’t take your influence with you. There’s no transitive Trump authority in Republican politics. In other words, he doesn’t have to hate you or denounce you. But if he doesn’t support what you’re doing—and Republicans know it—you’re on your own. Good luck with that.

When Trump shined his light on Roberts and Dans, they had all the authority they needed on the right. But when the Trumpian light goes out, you’re in the cold. In April 2022, Trump keynoted a Heritage dinner, saying: “This is a great group and they’re going to lay the groundwork and detail plans for exactly what our movement will do … when the American people give us a colossal mandate to save America.”

Roberts took that royal warrant and ran with it, raising scads of money as the head of Trump’s de facto brain trust. It was great while it lasted. Roberts got invited on all the right TV shows and podcasts. He got a book contract laying out his revolutionary agenda. People in the extended Project 2025 universe—the Steve Bannons and Stephen Millers—felt free to say scary and weird things about the “regime” and what they were going to do when they got unlimited power. They even got one of their own—J.D. Vance (who writes the foreword to Roberts’ book)—on the ticket.

There was just one problem. Other people were listening.

This is a perennial problem for a party and a movement that is organized around fan service. Project 2025 is just one facet of the whole disco ball of asininity. Self-styled radicals and revolutionaries tell the converted what they want to hear, but then are shocked that the unconverted are appalled or frightened by the same rhetoric when it is gleefully reported to the wider public. Vance’s “childless cat ladies” schtick sounded great to the already red-pilled. So did Roberts’ beer muscle boasting that the revolution will be “bloodless” if the left doesn’t resist. Every day, Steve Bannon—or whatever poltroon is subbing for him while he makes apple brown betty in the prison kitchen—spews garbage that is received as ambrosia by the basement-dwellers who hang on his every word. But there’s a reason MSNBC and the DNC probably have teams of interns transcribing every episode of Bannon’s War Room podcast.

Yesterday, I heard Fox News’ Jesse Watters recount that “the scientists” say that if a man votes for a woman he will “transition into a woman.” Now, I am sure there are dudes icing their recently tanned testicles, and maybe even a dozen Instagram “trad wives” who fist-pumped the air and shouted, “Hell yeah!” when they heard that. But for every one of them, how many dozens or thousands of people say, “That’s weird”?

(Oh and spare me the “you’re using Democratic talking points when you call them ‘weird’” crap. First of all, the party of Trump cannot, with a straight face, complain about “name calling” and insults. Second, a lot of the stuff these dudes say is weird. And, third, even if some of it isn’t—which is occasionally true—smart politicians avoid making it easy for their opponents to call them weird.)

I understand why acolytes of the Trump cult get confused about all of this. After all, Trump is constantly feeding red meat to his fan base, and he doesn’t pay a price for it. Why can’t they?

The answer gets us back to the challenge of unitary Trumpism. Many do get away with spouting nonsense for the most part. But the weirdness of the rhetoric isn’t dispositive. What matters is when the weirdness proves inconvenient for Trump. When that happens, Trump excommunicates them. What constitutes inconvenience can vary. Sometimes you can get defenestrated simply because you steal his limelight or mitigate his revenue stream. Criticizing him is obviously out of the question, but we’re not talking about critics—they were purged from Trumpworld a long time ago. But the surefire way to get anathematized is to hamstring him politically. Just scour the political graveyard, and you’ll find the careers of countless cabinet secretaries, congressional representatives, and senators who proved inconvenient to Trump.

And this gets to the real stupidity underlying Project 2025 and countless other efforts to take the crooked timber of Trump’s character and make it fit some straight-line theory of Trumpism, MAGA, America First, or conservative principles generally: He doesn’t care.

There is no ideology, no policy agenda, no definition of principle or character that Trump will ever subordinate himself to, because he considers himself above such things.

As the editors of the Wall Street Journal—who have some bruises and scars to remind them of such folly—noted, Roberts’ “mistake was thinking that Mr. Trump cares about anyone’s ideas other than his own. He governs on feral instinct, tactical opportunism, and what seems popular at a given moment.” I agree with this, but I’d add the proviso that he really doesn’t care all that much about his own ideas either, save his idea of himself as infallible and strong. If you want to call glandular impulses “ideas,” then, sure, he cares about some ideas.

A bit further on, the Journal offers some advice: “The lesson for Heritage, and other think tanks, is that it’s better to stick to your principles rather than court the political flavor of the day. And never trust a politician.” Obviously, I agree with that, too. But that advice should not be limited to think tanks alone. It’s good advice for the Republican Party, conservative media, donors, and voters, too.

Donald Trump is the snake. He does what he must.

And it has always been thus. To paraphrase the street peddler in Conan, 8 years ago, I thought it was just another snake cult—and I was right! That’s why I am incapable of being shocked by that behavior. But I am capable of being shocked—or at least amused—when his enablers are surprised to find themselves playing the role of the old woman.

In the heart of D.C., where ambitions brew,

The Heritage Foundation found a snake,

He promised to make America new,

They thought, “What a promising take.”“Oh, naive wonks,” the snake did cry,

“Won’t you give me shelter and care?

I’m Donald Trump, give me a try,

I’ll make the nation fair.”The Foundation, seeing dollars bright,

Brought him in from the storm,

“With our wisdom, you’ll lead the right,

And we’ll keep each other warm.”They showered him with strategy,

Plans to make the country strong.

He nodded and smiled, seemingly with glee,

As they helped him along.But once he’d gained a foothold, sure,

The snake began to twist.

His love of self remained so pure,

The Foundation’s dreams dismissed.He reveled in the spotlight’s glare,

His ego paved the way.

His positions showed that he didn’t care,

About anything they’d say.“Oh, snake!” they cried, “Why did you feign?

We trusted you with care!

You’ve left us out in the rain,

Your selfishness laid bare.”The snake just laughed, a selfish grin,

“You knew my nature well,

You forgot I must win,

Now you can go to Hell.”He left them there, ambitions crushed,

As he pursued his own acclaim.

The Foundation, feeling foolish, hushed,

Had only themselves to blame.

I’ll show myself out.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.