There is something beyond broken about our nation’s discourse on masculinity when the most popular cable news host on the most popular cable network produces a special on American men in crisis and it features testicle-tanning. Yes, feast your eyes on a man on a pile of rocks, groin aglow with radiant red light:

The picture is rooted in two highly dubious assertions. First, that male testosterone levels are falling dramatically. And second, that exposing your genitals to red light can boost testosterone production.

The New York Times took a look at both assertions, and neither truly holds up. Turns out that we don’t really know how testosterone levels compare over time:

Studies examining changes in testosterone over time are challenging for several reasons, including difficulties in recruiting large populations of normal subjects, daily circadian changes in testosterone, and differences in testing methods over time, noted Dr. John Amory, an expert on male reproductive health at the University of Washington.

And how about the red light? Well, here’s the “evidence” that it works:

Scott Nelson, co-founder of Joovv [the company that makes the red-light device], said in an email, “The published data around light therapy and testosterone production is pretty light, but the limited evidence is fairly compelling.”

He provided a link to a study on the Joovv website, apparently unpublished, reporting that red light worked best to boost testosterone in four men who were also on a ketogenic diet.

I’m no scientist, but I’d say that calling the evidence “pretty light” is an understatement. But hang with me for a moment readers, I’m using Carlson’s hysterical nonsense as a launching pad for a different kind of conversation about masculinity—a conversation about stoicism. Or perhaps a better way of stating it is that we need a conversation about calm.

Ever since I’ve been alive, our culture has been in a conversation about male emotions. My entire adult life there have been voices urging men to “open up,” to be more emotional—to avoid the “toxic” male trait of emotional restraint.

In fact, in 2019 the American Psychological Association published guidelines declaring that “traditional masculinity is psychologically harmful and that socializing boys to suppress their emotions causes damage that echoes both inwardly and outwardly.” The report repeatedly condemned what it called “emotional stoicism” or “male stoicism.”

The APA connected stoicism with a number of other allegedly masculine traits such as “competitiveness” and “aggression” to paint a picture of the unhealthy man. A number of conservatives (including me) strongly objected to this formulation. Whether stoicism, competitiveness, or aggression are vices or virtues strongly depends on context. Each characteristic has its place. Each characteristic can be abused.

For example, competitiveness can consume a person, turning him into a monster who steamrolls everyone in his path. Or competitiveness can serve as a spur to creativity and profound achievement. Sometimes it does both at once.

Even aggression can be a virtue. Right now in the nation of Ukraine we’re watching aggression at its worst and best. There are times when evil has to be confronted head-on, with extreme violence.

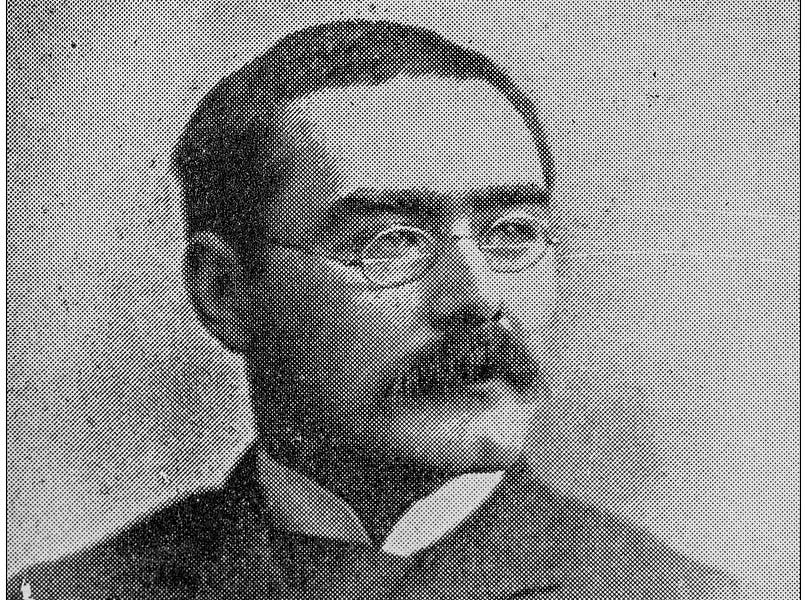

Stoicism also has value. In the legendary poem “If,” Rudyard Kipling begins his description of masculinity with stoicism as a virtue (“if you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs …”), and a sense of calm amid a storm is of undeniable value. Yes, there’s such a thing as too much repression, but there is also such a thing as too much emotion.

(And yes I know there is nothing uniquely masculine about any of the traits above. But they’ve been singled out in the masculinity debate, so bear with me.)

In moments of crisis or trouble, do you look to the people who are losing their minds? Or do you find yourself immediately gravitating to those who remain calm?

I’m reminded of an amusing moment shortly after I returned from Iraq. I was back with my reserve unit, and a young soldier called one of our veteran officers and declared that he was dealing with a “crisis.”

“A crisis?” The officer answered. “Are there body parts on the floor?”

The soldier paused, obviously confused. “No sir.”

“Well then, we’ve got a problem, not a crisis. Let’s deal with it.”

The point was made. Don’t automatically escalate the stakes of any given problem. Pause. Take a breath. Decide the proportionate response.

But here’s my concern. In the furious battle over masculinity, both sides have won in the worst way. The emotionalists have triumphed, but so have the aggressors. In other words, all too many modern men have indulged both their aggression and their emotion, and the result is our modern discourse, a discourse plagued by hysteria, threats, and malice.

This is the cardinal characteristic of much of the culture of the new right. It is considered a sign of strength to be constantly turning the volume to 11, constantly forecasting doom, and constantly chasing the latest fads to “fight back.”

Once you see the pattern you can’t unsee it, and in fact if you want to see many men on the new right get really emotional, argue that a problem isn’t a crisis. Listen to talk radio for just a few minutes. Hear the rage. Watch Tucker’s special. See the alarm.

But don’t for a moment think aggressive emotional hysteria is confined to the men of the new right. It’s a standard form of discourse in deep woke America. The only real distinction is that it’s not defended as distinctly masculine, but it’s present nonetheless.

Last week I had the pleasure of speaking to a room full of young men at Hampden-Sydney College, one of the last all-male colleges in America. I walked through the “traditionally masculine” characteristics that the APA condemned, and argued that the goal of a young man wasn’t to shun stoicism, competitiveness, or even aggression, but rather to intentionally shape these characteristics so that potential vices can become cardinal virtues.

And when we survey the American political and cultural landscape—a landscape that is awash with male emotion and male aggression—perhaps it’s time to rediscover a dash of male stoicism. Keep your head, strive for the proportionate response, and don’t let anyone blame you for refusing to lose your calm.

Otherwise you might just be intemperate enough to look at a man on a rock, tanning his testicles, and think, “He’s saving men.”

One last thing …

If you haven’t listened to Advisory Opinions recently, now’s the time to dive back into The Dispatch’s flagship podcast. Given the week’s headlines, I’d strongly urge you to listen to last Thursday’s episode. It contains everything you need to know about the merits of the federal court ruling enjoining the federal transportation mask mandate and the legal issues raised by Ron DeSantis’ war on Disney.

Give it a listen. You’ll be glad you did.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.