Dear Reader (Including those of you who get involved in a land war in Asia),

I don’t often say this, but good for Rachel Maddow.

“I feel like I’m going to have to rewire myself so that when I see someone out in the world who’s not wearing a mask, I don’t instantly think, ‘You are a threat,’” Maddow said last night. “Or you are selfish or you are a COVID denier and you definitely haven’t been vaccinated. I mean, we’re going to have to rewire the way that we look at each other.”

I definitely understand why she’s getting a lot of criticism from the right for this monologue. And I agree with some of the points people are making in response to it. But the fact is, she’s right.

Now, I don’t mean she was right to instantly think anyone without a mask was a selfish, COVID-denying threat. I mean she’s right that she and a great many of her viewers are going to have to get over that. And she’s right to say it to her audience. Alas, she clearly has more work to do:

A lot of the people dunking on Maddow seem to have forgotten that, when the pandemic began, there were plenty of people on the right who believed that mask-wearing was a window into your soul, too. My favorite entry in this crowded field remains Cheryl Chumley’s opus titled, “Coronavirus masks turning Americans into good Asian comrades.” According to Chumley, masks were the tip of the spear of a new Yellow Peril, driving Americans to “adopt an Asian cultural identity.” Masks, Chumley went on, are “kind of like the red belts worn by the communists when they want to show solidarity, when they want to make public expressions of party loyalty, when they want to display their sacrifice of self for the greater good.”

Chumley was hardly alone. Rush Limbaugh derided masks as a “symbol of fear,” and the Trump White House literally became a superspreader site by kowtowing (in Asian cultural fashion) to this obsession.

It would have been good if the Rachel Maddows of the right pushed back on this stuff more—or at all—at that time in the same way that Maddow is now.

Of course, Maddow is very late to the game, and even now she’s not admitting—or telling her audience—that it was wrong to make masks a cultural signifier in the first place. While I think Chumley’s argument was idiotic, it was obvious that the left’s embrace of the pandemic as a vehicle for the culture war would elicit a similar culture war response from the right.

Randolph Bourne, a liberal thinker who resisted the siren song of nationalism, progressivism, and social engineering that seduced so many in the lead up to World War I, noted how there was a “peculiar congeniality between the war and these men” who leapt at the opportunity to seize the crisis for their will-to-power. “It is,” he sadly observed, “as if the war and they had been waiting for each other.”

The pandemic played a similar role for a host of experts and the progressives who have an unscratchable itch for technocratic command-and-control governance from above. Again, I think the populist response to hectoring and mask fetishization was often an equally unhelpful counter-overreaction to the initial progressive overreaction. But the right-wingers had a kind of self-awareness that progressives didn’t, because the progressives assured themselves they were the data-driven devotees of science.

And that overreaction continues.

As Charlie Cooke notes, some seem to lament the CDC’s new mask rules precisely because they will no longer have the convenience of seeing masks as shorthand for “people I hate.” The debate now is “how can we tell if someone was vaccinated?” as if this were a hugely important question. “The next question is going to be, ‘How will we know if someone has been vaccinated?’” asked Dr. Michael Osterholm on Morning Joe. “If you’re sitting close to someone at a restaurant or … in a theater, how are you going to know that they’re not just kind of fibbing?”

My own response to this is, basically, I don’t care. I’m vaccinated. My family and friends are vaccinated. I’d like the people sitting next to me to be vaccinated too—for their sake. But I really don’t care very much, because even if they’re contagious, I’m extremely unlikely to get COVID. And if I do, the symptoms are going to be mild. That’s what the science says. And to borrow a phrase, I believe The Science.

On that note, let me change gears a bit.

Belief and faith.

“Belief” is a funny word.

It is very close to the word “faith,” but just different enough to be interesting.

If you google “faith versus belief,” you get a lot of websites teasing out the differences in the context of religion.

We can get to that, but in my own mind, I think the difference is that “faith” is the more honest word, because “faith” implies you know you’re making a kind of leap of, well, faith. You’re committing to a belief that you understand other people might not be able to adhere to or agree with. A “leap of belief” sounds funny, because “belief” suggests you’re opinion is supported by facts or an argument while faith acknowledges you’re putting your trust in something beyond the realm of the provable or obvious.

It’s the difference between hope and probability, I guess. “I have faith the Jets will make it to the Super Bowl” is the triumph of hope over experience. “I believe the Jets will make it to the Super Bowl” suggests you know something everyone else doesn’t. The faithful are less likely to take a bet than the believers.

The problem, however, is that a lot of people actually mean “faith” but use “belief.”

It seems to me that most of the time, when people say they “believe the science”—or even worse, when they say they “believe in science”—what they really mean is that they have faith in it. More specifically, they mean they have faith in a very narrow slice of “science” that comports with their political or cultural priors.

We’re all believers.

Before I go on, let me make something clear. Very few people don’t believe in the broad category of procedural inquiry known as science.

The Amish believe in science, they just keep it at a kind of cultural and religious distance.

Phrenologists, flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, global warming “deniers,” and creationists believe in science; first of all, they’ll all concede that science, well, exists as a human endeavor in the same way that economics, engineering, linguistics, and art exist. If you’ve ever read Michael Behe, who is the foremost advocate for intelligent design, it will have been clear to you that he believes science is on his side. I mean, he teaches biochemistry at Lehigh University, which is a pretty good school for that kind of thing.

I’m not saying I agree with him, but that’s irrelevant to my point. Virtually every person who falls into the category of “science denier,” among the sorts of people who use that phrase, doesn’t actually deny science. Rather, they simply disagree with, or are otherwise unpersuaded by, some scientific finding or claim. Calling someone a “science denier” is almost always a logical fallacy: the appeal to authority. It’s also often a form of intellectual or social bullying. Again, many of the people accused of denying science are wrong, and sometimes they’re dishonest, but very few of them dispute the existence or even the authority of science to settle certain claims.

The religion of humanity.

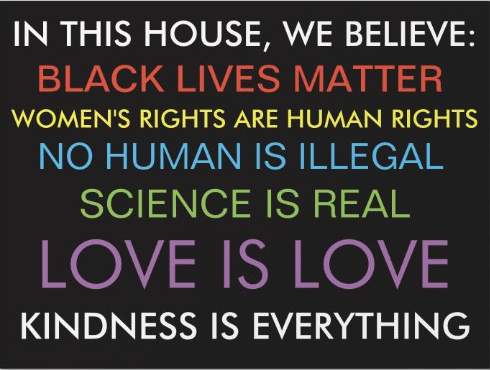

Which brings me back to faith. Every morning I pass at least one house with a yard sign that says something like the following:

What’s interesting about these declarations is that all of them are moral, cultural, political, and/or spiritual assertions, including the phrase “Science is real.” Again, taken literally, the phrase “Science is real” is a rebuttal to a straw man, because pretty much everybody believes science is real. But I think most people don’t mean it literally, or at least don’t realize that they don’t mean it literally. The whole thing is a declaration of faith.

There’s a really deep and long-running debate about whether science can or should be a source of morality. I have many opinions on the question, but I think it’s ultimately a distraction. Nobody actually wants to derive their moral system from science, including the people who believe or claim that’s exactly what they want to do. To put it more plainly, nobody can do that.

I’ve written countless times that the people who say “Believe the science” or invoke “settled science” are perfectly happy to reject the most authoritative conclusions of science when those conclusions run against their larger worldview. Climate change is an existential threat, but nuclear power istreyf regardless of what scientists say. Every decent medical textbook in the world (although this may have changed recently) says that sex is a category grounded in biological reality. Until recently, the most prominent anti-vaxxers, like Robert Kennedy Jr., were on the left.

But the most relevant example for the moment was what I called The Treason of the Epidemiologists. When the Black Lives Matter protests erupted, numerous people who’d been hectoring Americans about large social gatherings being dangerous and literally antisocial turned on a dime and said that protesting racial injustice was different—as if the virus would give the right kind of protests a wide berth.

My use of “treason” had nothing to do with them being unpatriotic. I was referencing Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals, a searing indictment of the intellectual classes at the beginning of the 20th century who forfeited their obligations to tell the truth out of loyalty to the pandemic of “isms”—socialism, nationalism, etc.—infecting the West.

When asked to choose between the dictates of their stated faith—“Science!”—and the tenets of the deeper faith, many of the high priests of science caved to the demands of their own acolytes. Of course, they had to rummage around in the hymnals to reconcile the contradiction, and claimed that racism is a greater public health threat than COVID. Maybe it is, although to my knowledge, 584,000 people haven’t died from racism over the last 14 months. But the idea that the Floyd protests would end racism was utter nonsense. And the revelation that epidemiologists—and all those countless Maddows and Hoggs among the Very Online hung on their every word—didn’t really “believe the science” when a more seductive narrative beckoned to them didn’t just erode trust, it signaled to millions of Americans that the disinterested experts had chosen a side in the culture war.

Longtime readers know that one of my favorite quotes comes from the philosopher Eric Voegelin: “[W]hen God is invisible behind the world, the contents of the world will become new gods; when the symbols of transcendent religiosity are banned, new symbols develop from the inner-worldly language of science to take their place.”

Science is good and hugely important. And while I don’t think it’s a source of morality, I do think it’s a source of truth, which is essential to morality. I don’t subscribe to the most extreme and literal interpretations of David Hume’s famous declaration that “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” I think reason is often directed by the passions, but passions can be informed and modified by reason. If that was not so, we would never stop being children, quick to anger or tears over reality’s refusal to bend to our immediate wants and desires.

But the belief that science always confirms our wants and desires is itself a form of childishness. It’s also an act of faith that is deeply unscientific. God doesn’t just tell us what we want to hear; that’s closer to the Devil’s schtick. When God didn’t ratify the Israelites’ desires on their timetable, they drafted a god they believed would indulge their childish tantrums. That’s what people do when they insist science is on their side. Science is not God and God is not science. You can try to be on their side, but it is childish folly to assume they’re always on yours.

Various & Sundry

Canine update: We’ve got to take Pippa to the vet. Years of spanielly exuberance are clearly catching up with her. She’s really not moving right these days, and she still refuses to fully understand her limits. A case in point: She and Zoë have recently figured out that they can work together to police rabbits in our neighborhood. We never walk Zoë off leash in the neighborhood because she’s not good with small dogs and she’s great at chasing varmints (although we do walk her on one of those long extendo-leashes). But we do keep Pip off leash for the most part because she follows commands and is no threat to humans or dogs. She’s also an amazingly good rabbit wrangler. She goes off into bushes or tall grass and flushes out rabbits expertly. And she’s now figured out how to steer them toward Zoë—or, perhaps Zoë has figured out how to pre-position herself.

It all happens so fast that it’s hard to figure out where the real expertise is. Either way, our neighborhood walks now require constant vigilance because the hoppiness of bunnies fills Zoë with intoxicating rage. She’ll still chase squirrels on occasion, even though it’s mostly pro-forma at this point. But bunnies? How dare they bounce around like that and refrain from running up trees. So far we’ve avoided any new kills. But it’s been close. And when we stop Zoë from delivering dingo justice, she comes back to the house muttering and arooing her resentment. I caught her writing an email to her union rep the other day complaining about it.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.