Hi,

There’s a hoary old thought experiment I want to fiddle with.

It goes something like this: Imagine if I showed you a button and said, “If you press this button I will give you $1 million, but one random person will die as a result. No one will know. You will probably never even know who it was you killed.”

You’ll be surprised—or maybe you won’t!—by how many people say “yes” to this offer. There’s even a website dedicated to an even starker version of the question; 10 random strangers will die. As of now, nearly two-thirds of the people who took the poll say they’d press the button. In the comments, you can see the rationalizations—posing as rank utilitarianism—flow:

“People die every day. At least something good may come from it.”

“Just use some of the money to save at least 11 people and it will be all good.”

“Those are strangers, i don’t give a f**k. Peoples die by thousands every days, 10 more or less, who cares?”

Here’s the thing. If I gave you a good sniper rifle and made you the exact same deal—but instead of a random person you won’t ever see I said, “Shoot one of the random people in that park across the street!”—the moral issues do not change in the slightest, but the psychological ones change a lot. My guess is fewer people would take the deal. But fewer is not zero.

Let’s be clear: The button-pushers are murderers every bit as much as the trigger-pullers. The only difference is that the trigger-pulling feels less murdery than the button-pushing. Murder for hire is murder for hire. The technology you use is entirely irrelevant.

Now, there are philosophers who passionately disagree. While ultra-utilitarians would reject murder for personal enrichment, if you used your proceeds to save the lives of, say, 1,000 children, they’d say killing one person would be worth it. The gross domestic benefit of society should be the ultimate consideration.

There have also been countless regimes—from Aztec human sacrificers, to medieval kings, to Nazi, communist, and Maoist rulers—who’ve made similar calculations in the name of the “greater good.” It’s not as neat and tidy as the thought experiments described above. The rewards were more ephemeral and the murders more numerous, but the utilitarianism is the same.

What is liberalism?

I bring this up to make what should be a really obvious point. You can’t give anyone the kind of unrestricted power to make these decisions. Liberalism, heavily influenced by Christian and Jewish notions of morality, is a system humans came up with to prevent decisions like this from being made. In practice, it hasn’t always succeeded. But in principle, liberalism looks at human beings as ends unto themselves, with innate dignity, who cannot be sacrificed arbitrarily in service to their rulers’ conception of the highest good. Monarchs and emperors, just like Bolsheviks and Nazis, often killed categories of people for the good of the realm or cause.

Not to beat a dead horse, but this is why I keep insisting that liberalism is not a system of “neutral rules.” It’s a profoundly moral system designed to constrain arbitrary power and protect citizens from those with the power—borrowing a phrase from the mob—to “push a button” on other people. The president has no more right to press a murder button than anyone else.

I started with all of this murder talk simply to illuminate the principle. But liberalism is far more morally ambitious than a simple system of murder prevention. The right to life is simply the first of many rights that liberalism is supposed to protect. It also protects the right to worship, speak, move, etc. as you like. It protects the right to be secure in your home and to own your property. Obviously, none of these rights are absolute, but their limitations are bounded by the sovereignty of the rights of others.. More practically, these limitations are delineated by the law. And the law derives its legitimacy not from the personal authority of any politician, but by the process we shorthand as “democracy” and its foundations, such as the Constitution.

The dual threat.

There are, broadly speaking, two perennial threats to this morally glorious system. One comes from “above” and one from “below.” The threat from above comes from elites—experts, technocrats, would-be oligarchs, etc.—who think they know better. They think they’re smarter than the market, don’t have time for the messiness of politics and the democratic process, and should just be allowed to impose “optimal policies” from above regardless of the rules.

The threat from below shares many of these same assumptions, but their complaints are couched in the language of grievance and entitlement. This is, of course, populism. Populists insist that the rules are unfair to them so the rules should be ignored.

Usually—but not always—the system can fend off either threat individually. But when the two combine, the system gives way. As I wrote the other week, “The worst form of elite agreement is usually the product of politicians pandering to populist sentiment. When both parties serve as vessels for popular passions, they ignore experts and the lessons of history, and they suspend their own critical faculties.”

I was writing about Biden’s “Buy American” blather. But the point is more universal. McCarthyism ultimately failed because it couldn’t find lasting purchase among elites, but plenty of damage was done from above and below before it petered out. The internment of the Japanese and the countless crimes against decency of the Wilson and Jim Crow eras are examples of elite factions exploiting popular passion in a pincer move against unpopular minorities and the laws intended to protect them.

I started talking about murder because murder is morally clarifying when talking about where to draw lines. Similarly, most reasonable people can see what I’m getting at when I’m talking about rounding up Japanese Americans or lynching black people. But our vision gets cloudy when we talk about “nice” things that don’t bluntly ping our moral intuitions.

I have little doubt that if you asked Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren, “Would you push a button that transferred 75 percent of the net worth of billionaires to the bottom quintile, even if it was indisputably illegal and unconstitutional?” that they would. And even if I’m wrong about them, I have no doubt many of their fans would take that deal in a heartbeat.

The illiberalness of debt cancellation.

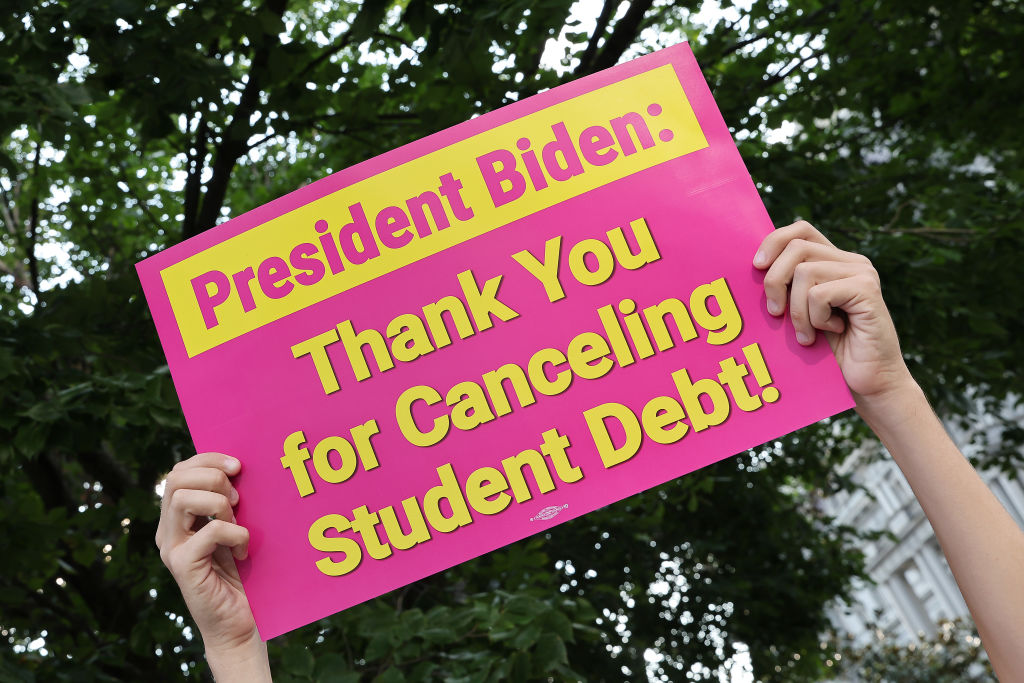

Which brings me to the “debate” over Joe Biden’s scheme to forgive—such a monarchical word!—the student loan debt of millions of people who just so happen to make up a big chunk of the Democratic coalition.

I believe the legal argument behind this scheme is a hot mess. I don’t think it’s close. He doesn’t have the power to do it under the HEROES Act or the Constitution. It is simply lawless. If then-President Donald Trump tried to unilaterally order the cancellation of vacation home mortgage debt, a lot more people would recognize the problem. But because young people, disproportionately people of color, are the intended beneficiaries of this abuse of power—and because they feel like it should happen—many in the press think it’s either complicated or entirely justifiable.

Note: If you disagree as a legal matter, that’s fine. Make the argument. If you think that the policy is right, that’s fine too. But I can list policies I think are right all day long that I nonetheless don’t think the president of the United States can implement by ukase. Liberalism is moral. But it’s a moral system with a defined process. Ignoring the process simply because the goal is “good” is illiberal.

This morning I heard my friend Steve Inskeep on NPR read from an Associated Press article about how some of the people in the courtroom were carrying a lot of student debt and they wanted the court to uphold Biden’s plan. The point of the article was that they were, in Inskeep’s words, “offended” by the legalisms being debated before the court. Heaven forbid a court of law get mired in the meaning of the law! “It just hurt my feelings a bit,” one of the observers said. “I just want better for us, you know?”

“They were focused on small, minuscule details,” another observer told the AP. “I even saw some of them laughing during the hearing, which was odd to me because people’s lives are being affected. It’s not a laughing matter to us, at least.”

I’m fully capable of sympathizing with struggling people who’ve had a life-changing windfall of debt cancellation dangled in front of their noses. But their feelings are utterly irrelevant.

You know what else is irrelevant? The fact that most of the justices are wealthy. Under the headline, “College debt relief program rests in the hands of nine wealthy and elite people,” Devan Cole at CNN (where I am a contributor) penned an “analysis” piece lamenting that the case would be decided by “a small group of jurists who are far from being representative of the borrowers that could benefit from the relief.” This piece would never have been written if the court majority were a bunch of rich liberals bent on approving Biden’s scheme.

This is the corrupting logic of populism. I mean, who cares? If you want a representative body to forgive student debt, we have this thing called “Congress” that is empowered to do just that. Most of its members are literally called “representatives.” The Supreme Court isn’t supposed to decide questions of law based upon the emotions or socioeconomic status of the affected parties—never mind the justices. It’s supposed to decide questions of law based upon—you could look it up—the law.

Justice Sotomayor argued that the claim that the HEROES Act (passed in 2003) was never intended or written to allow the cancellation of student debt for non-military personnel during a pandemic-related state of emergency nearly two decades later was simply a semantic quibble. Judges shouldn’t make this call, she said—we should leave it to the unelected bureaucrat who works for Joe Biden to make it:

And what you’re saying is now we’re going to give judges the right to decide how much aid to give them. Instead of the person with the expertise and the experience—the secretary of education—who’s been dealing with educational issues and the problems surrounding student loans, we’re going to take it upon ourselves, instead of leaving that decision in the hands of the person who has experience with these questions.

Why should the “experts” be left to make the call? Because “There are 50 million students who will benefit from this who will struggle …” if the experts can’t have their way. Let the experts push the button. They know best.

This is the corruption of elitism—married to the corruption of populism. I mean, we’re talking about a lot of people!

Again, I oppose the policy for reasons I’ve written about many times. But if you want the policy, pass a law (that can pass constitutional muster).

I’ve been inveighing against the cult of experts and the dangers of populism for 20 years. This used to qualify me as a fairly conventional conservative. But we now live in an age where populism and rulers who cater to them are good for me, but not for thee. I haven’t changed my views at all on this stuff, save in one regard.

I never fully appreciated that populists who claim to hate elites who arrogantly and arbitrarily wield power as they see fit, actually want elites to arrogantly and arbitrarily wield power, but just for them. Populists want kings, and kings want to claim they are tribunes of the people.

I want the law.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.