Hey,

Some of you may recall this from my eulogy for my dad. When Roone Arledge, the longtime head of ABC Sports, died there was a remarkable outpouring of praise for his genius and outside-the-box creativity. Specifically, his invention of Monday Night Football and The Wide World of Sports.

My dad had a dry sense of humor, and he delivered it dryly when speaking. In email it was like ordering an extra-dry martini that was so dry you asked to hold not just the vermouth but the gin too: “Just give me a glass.”

He sent me an email: “Only now do I realize what a genius Roone Arledge was. Who else could have figured out that viewers would like to see more sports. As you know, ABC had been considering The Poetry Hour until Arledge stepped in with his groundbreaking sports idea.”

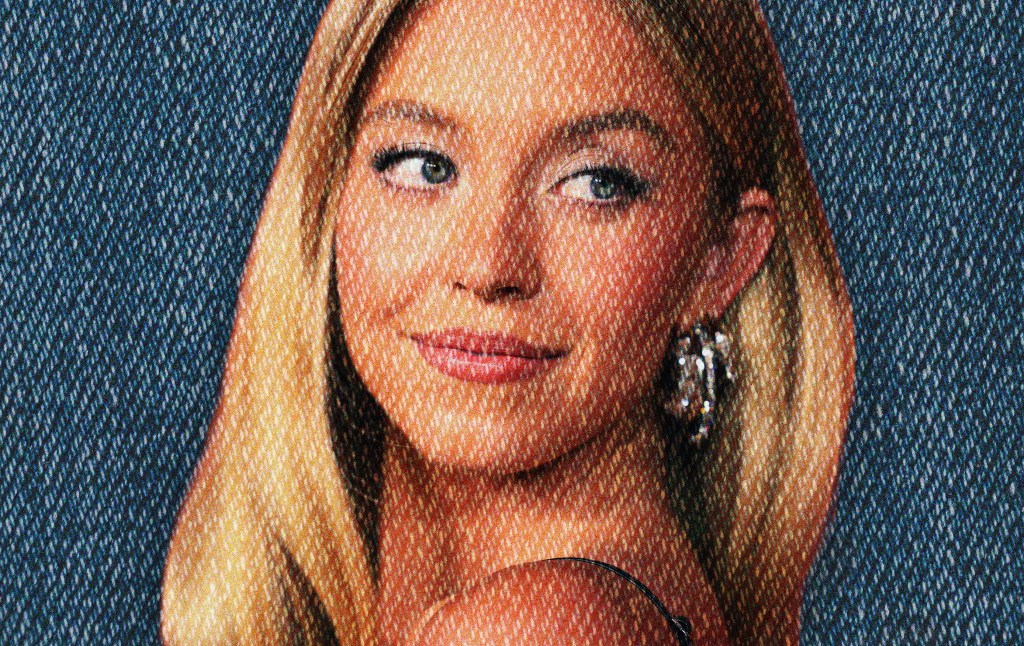

This is sort of how I feel about the Sydney Sweeney “controversy.”

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of The G-File. You can read Jonah’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

If you don’t know about it, good for you. But here’s the gist. Apparel retailer American Eagle hired Sweeney, a classically, uh, buxom? curvy? (I need tasteful adjectives to describe how she attracts the male gaze) blonde actress to pitch their jeans. They came up with some wordplay about how she has “good jeans.” But it’s a play on “good genes.” Indeed, in one viral ad she crosses out the word “genes” and replaces it with “jeans.”

Get it? Well, it doesn’t really matter, because when it comes to Sweeney, she’s a lot like the old Playboy magazine—the words aren’t really the point. I mean, she could have crossed out the words “hapax legomenon”—or an actual hapax legomenon—and it wouldn’t matter. No one is showing up to this class for the assigned reading.

In case there are a few of you who didn’t know, a hapax legomenon is a word of which there is only one recorded use.

But the reaction to the ad campaign is as if this is something like a hapax legomenon for advertising. The Mad Men who conceived of this campaign, in the minds of some critics, are madmen who have violated some taboo, crossed some Rubicon, trampled some norm, with this shocking scheme to hire a popular hot young blonde who can expertly fill out a sweater with plenty of room left over for a pair of Daisy Dukes, to sell jeans. Who was the evil Madison Avenue Roone Arledge who came up with this idea? Was Robert Reich unavailable?

Did Elena Kagan refuse to take the gig on some ethical grounds?

Now, I’m leaving out the pretext for the outrage. Apparently, the phrase “good genes” is a eugenics term that literally gave us Hitler. And given the fact that Sydney Sweeney is a blue-eyed blonde, the ad must be intended as a dog whistle—or foghorn—shouting “Nazism is awesome.”

Yes, I am sure that some 25-year-old incel has laid down his tiki torch and his copy of Mein Kampf, as he eased into his race car bed in his parents’ basement and asked an AI program to draw Sweeney in an SS uniform riding a winged horse like an updated Valkyrie in pursuit of Aryan onanism. The heart wants what the heart wants, and all that.

But come on. Amber Raiken, of The Independent, tells us that “the phrases ‘good genes’ and ‘great genes’ have historically been used in the language of eugenicists, who believe the human race can be improved genetically by selective breeding.” An MSNBC headline declares, “Sydney Sweeney’s ad shows an unbridled cultural shift toward whiteness.” The subhead provides crucial context, lest you had any doubt that “whiteness” qua “whiteness” is bad: “Advertisements are always mirrors of society, and sometimes what they reflect is ugly and startling.” Salon informs us that “Eugenics movements in the U.S. often promoted the idea of ‘good genes’ to encourage reproduction among white, able-bodied people while justifying the forced sterilization of others. Critics say those ideas still show up in modern advertising and influencer culture, often unexamined.”

A professor of something told an ABC morning show, “The pun ‘good jeans’ activates troubling historical associations for this country. The American eugenics movement, in its prime between 1900 and 1940, weaponized the idea of good genes just to justify White supremacism.”

Now, the American eugenics movement—an overwhelmingly progressive movement—is something I actually know quite a bit about. And it is absolutely true that the idea of “good genes”—though contrary to a lot of these critics, not necessarily that term—played a big part in the thinking of eugenicists. Progressive legal icon Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the opinion ordering the sterilization of Carrie Buck because he thought “three generations of imbeciles is enough.” While it’s obviously the case that many American eugenicists were white supremacists or racists, the eugenics movement began with, and largely focused on, the aim of cleaning up the white gene pool. Carrie Buck was not black, after all.

And while I loathe passing up on a good news peg to talk about eugenics, the simple fact is that this whole brouhaha is too stupid to take that argument seriously.

Yesterday, I was talking to Declan Garvey, The Dispatch’s executive editor, about our general policy to avoid clickbait-y topics just to get pageviews. I sheepishly said I was thinking about writing about this, and he chuckled about my intended violation of our policy. But then I mentioned that I had done an N-gram search for the term “good genes” and he said something like, “Well, if it includes an N-gram table, it’s probably okay.”

So here ya go. If you search for mentions of “good genes” in the Google book N-gram viewer, you’ll discover that there are basically no mentions of the term until the early 1970s. And it takes off like a rocket after that. I don’t want to get deep in the weeds here. But the American eugenics movement started to die in the 1940s, and the reckoning with its legacy began in earnest in the 1970s at the precise moment the term started taking off.

If you search Google for things like “good genes” and “ESPN,” you’ll find countless stories about athletes—including many, many black athletes—and how they have, you guessed it, “good genes.” You can do the same thing with “good genes” and “cancer,” “good genes” and almost anything and you’ll find scads, piles, heaps of usages that have no connection to Francis Galton (widely seen as the founder of eugenics) or, well, Hitler.

It’s particularly widely used in skin care discussions, for black people, white people, and every other kind of person found in the old Benetton ads. TMZ even had a recurring feature asking “Good Genes or Good Docs?” (as in good plastic surgeons). And of course, there’s a skin care product made by Sunday Riley called, “Good Genes.” We all know that Sunday Riley is just the Americanized name for “Joseph Mengele.”

The Washington Post has an explainer piece with the headline “How American Eagle’s Sydney Sweeney ‘good jeans’ ad went wrong.” It’d be nice if the paper had searched its own archives for the numerous times it has used the phrase. Eva Longoria, who will never be cast for a remake of Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, told the Post in 2015, “I’m lucky to have good genetics and great olive skin.” And she’s right! The New York Times has used the phrase countless times as well, without conjuring any troubling associations. Unless I’m missing something in the headline “Secret to a healthy, long life: Good genes, better exercise.”

Earlier I said that this whole kerfuffle was a pretext, because that’s what it is. If American Eagle had launched the campaign with Zendaya, Sweeney’s co-star in the TV series Euphoria, most of these critics wouldn’t care. And if they did, they would salute the transgressiveness of it.

Normal people use the phrase “good genes” to describe not intricate Nazi breeding programs, but the fact that they’re blessed with endowments or abilities they didn’t have to work for or didn’t have to work very hard at. Not one person in a thousand says, “I have good genes” to suggest that they are the culmination of a generations long breeding scheme like Paul Atreides in Dune (a movie Zendaya starred in, to the outrage of no one).

If I can an add a note of seriousness to this, if you have no problem with the term “good genes” when used by and about black or brown people, but suddenly become outraged when used for a white person and start spewing theories about the evil of “whiteness”—you’re the one with a racial prejudice problem.

There are a lot of people who need to justify their college majors by trotting out potted theories of “problematic” texts and symbols. They have audiences that love this crap, so the incentives are all there to lean into it. Their schtick then gives permission and similar incentives to the other team to mock it, which just encourages Team A to double down on the nonsense, and so it goes on.

And that’s what’s so annoying about this. This ad campaign didn’t go “wrong,” as the Post claims. It went better than American Eagle even dared to dream. I mean even The Dispatch is writing about it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.