Hi all,

Longtime readers of mine might recall my argument that Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan was the most conservative movie of the 1990s. Then again, they might not. And at least some of you are newcomers, so I’ll recap.

A Simple Plan tells the story of three men in Middle America who find a bag of cash in the woods. One of the men, played by Bill Paxton, is a decent man with a pregnant wife and strong work ethic. He suggests turning the money in to the police. One of the other men, the town drunk, says they should keep the money: “It’s the American dream!” he yells.

Paxton replies, “You don’t find the American dream, you work for it.”

The drunk replies, “Well, then this is better!”

Once the trio steps outside the rules, lots of bad things happen, many of which are much worse than their original misdeed. But that’s sort of the point. Once you step outside the path of doing what’s right, then terrible and often unforeseeable things can happen.

I should note that this was hardly a novel plot device. From the scientist who bends the rules for a good cause to find himself suddenly beset by superintelligent sharks to the good man who just wants to provide for his family and finds himself to be a New Mexican drug lord and meth kingpin, the idea that moving outside the rules—of morality, law, or ethics—angers the gods, or God, is a staple of storytelling going back to the Bible and ancient Greece.

It should be obvious why this is a conservative message. I don’t mean politically conservative—although the line, “Don’t be too clever or cavalier about the rules, because the universe can bite back with unintended consequences,” covers a lot of my political worldview. Rather, I mean conservative in a more human, cosmic sense. I don’t buy the theological aspects of karma, but I think there is a very real version of karma.

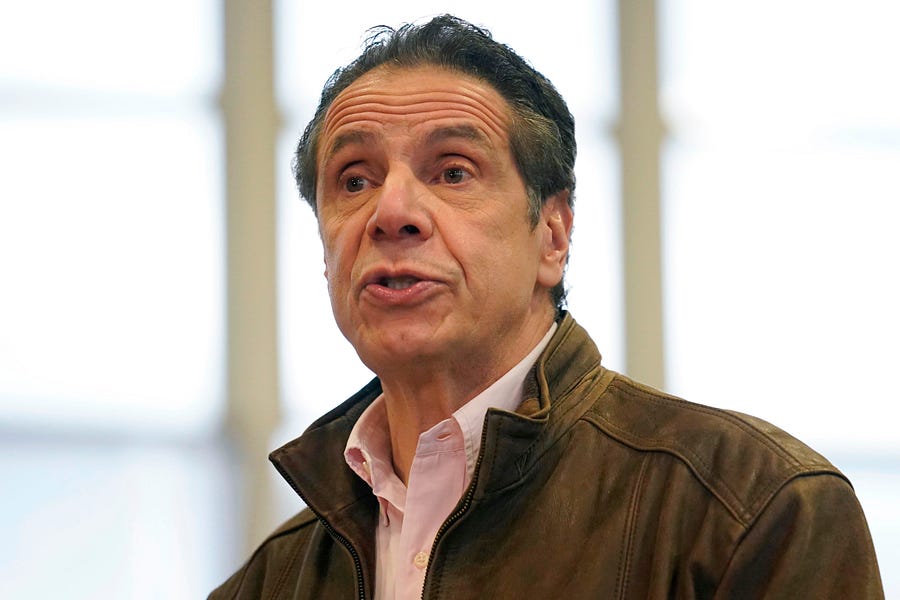

Let me offer some context: While recording the GLoP Culture podcast the other day, John Podhoretz asked whether it was wrong to feel a little cheated that Andrew Cuomo might go down for MeToo stuff rather than his handling of the pandemic.

I know what he means, but I disagree.

The perils of Cuomosexuality.

Here’s how I see it: The allegations of sexual impropriety leveled against Cuomo are bad. But to be honest, I’m not sure they merit the calls for his impeachment or resignation by themselves. Sure, they should—and almost surely will—end his political career going forward. Being a gross jerk is bad, but it’s not like he’s being accused of sexual violence. That said, the post-MeToo standards are real, and Cuomo and his party have been at the vanguard of the effort to establish them. One of the first rules of politics is that if you’re going to apply strict standards to others, you should adhere to them yourself. Craft that sword, wield that sword, live by that sword, and if necessary, die by it.

Regardless, even if you disagree with me and think these allegations are far more damning than I do, you’re going to have a hard time convincing me that they equate morally to what he allegedly did in the early days of the pandemic. We don’t need to get into the weeds of this. Suffice it to say that it looks like Cuomo made some very bad decisions that caused thousands of deaths—and then covered them up. Bad decisions made in good faith in a crisis are forgivable. Covering them up—particularly when public health experts desperately needed data on what was working and what wasn’t—is unforgivable.

Also—and this is where the karma stuff really kicks in—going around preening about your Solomonic wisdom and Churchillian leadership, literally at book length, is grotesque. Then there’s the fact that Cuomo was—and always has been—a nasty bully who browbeat and intimidated anyone who proved inconvenient to him. He might as well have been ringing a cowbell and wearing a sandwich board reading, “Come and Get Me, Karma!”

This scandal is a bit like the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man in Ghostbusters. It’s sad that Ray inadvertently thought of his beloved Stay-Puft when Gozer asked the Ghostbusters to choose the form of their destroyer. But karma, like Gozer, takes whatever form it pleases.

When I give career-advice talks to interns or college students, one of the things I always tell them is, “Don’t be a dick unnecessarily.” Obviously, this is a moral instruction, but it’s also practical advice. The person you permanently piss off in your 20s could be in a position who makes your life miserable in your 30s. Andrew Cuomo has been a jerk for decades, which is why so many New York politicians are racing to get their pound of flesh like sharks in a feeding frenzy.

Again, behaving decently to people is the right thing to do for its own sake. But it’s also an important way to accumulate social capital that you can draw on when you need it. Sure, this scandal would be rough on Cuomo no matter what, but it would be a lot easier to weather if he hadn’t spent his career belittling and berating people. It would be easier still, if he hadn’t handled this public health crisis badly and exploited it for political gain. In other words, karma isn’t a bitch, it’s your grandma—and grandma told you to be nice and don’t get a swelled head.

What are rules for?

But my point is much larger than “You should be nice” or “don’t lie.” There are other rules that fit into my understanding of conservative karma. Take Andrew Cuomo’s little brother, Chris. He’s a CNN anchor who spent much of the last year “interviewing” his brother in cutesy-wutesy fashion. He even used props.

It’s a fairly simple rule of journalism—whether written or unwritten—that (purportedly) straight journalists shouldn’t interview politicians they’re related to. Don’t get me wrong, I can see lots of exceptions if the point of the interview is their relationship. Chris Wallace interviewing his dad about his career in journalism is fine. But this was during an unfolding crisis and Andrew Cuomo was responsible for dealing with the worst outbreak in the country. This was schmaltz and pandering, nothing more.

But now that Andrew Cuomo is in trouble, Chris says he can’t cover his brother because there’s a conflict. He even manages to make this sound like some grand principle. I’m sorry (okay, not really), but this isn’t how rules work.

I’m sorely tempted to go into a long spiel about how rules evolve through a Hayekian process of trial and error and hence contain within them vast amounts of knowledge. For instance, the mom who says, “Wash your hands before you eat,” can be ignorant of the thousands of years of experience and knowledge accumulation that went into that rule and still benefit from it. Her kid can think he doesn’t need to wash his hands this time, and he might even be right, but the point is that simple rules are a way of dealing with risk.

Similarly, if you develop good habits of character, then you’re likely to be in fewer situations that require bad character. That’s the moral of A Simple Plan. If Paxton called the cops and handed over the money, he would never have to make horrible moral decisions.

If I’d been an executive at CNN, I wouldn’t have let Chris interview his brother for a host of reasons. It’s unserious. It conveys an insider-y—one might even say incestuous—attitude about journalism and politics at a moment when thousands of people are dying. But one of my top reasons would be: “What happens if, or when, your brother is in hot water?”

Following the rules, even when you don’t understand why they’re rules, isn’t a guarantee that karma will come for you. But it’s the best hedge you’ve got.

Karma chameleon.

Karma comes at you like water following the path of least resistance. I know lots of shady people in Washington. Some have gotten really rich and famous thanks to all of their corner-cutting. Some will go to their deathbeds without ever paying a just price for it (though one likes to think history will still render a judgment for some of them). But many ultimately pay some price, though perhaps not for the worst things they did. If you spend your life playing the odds that you can get away with being crooked or cruel, the odds will likely catch up with you.

Hillary Clinton arguably lost the election in 2016 because her husband’s record finally caught up with both of them when the karmic roulette wheel landed on MeToo and Donald Trump. I’m sure she thought it was unfair when Trump brought Bill’s alleged victims to that debate, and in one sense it was. But in the larger karmic sense, it was long overdue. Trump was her Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man.

Similarly, it bothers me that, as a political and legal matter, Donald Trump, Rudy Giuliani and others who lied about the election being stolen basically paid no price for their role in the Capitol riot. But if they end up being crushed in a lawsuit by Dominion Voting Systems, or if the ill will they’ve earned leads some opportunistic prosecutor to refuse a plea deal in some unrelated case, I’ll take it. It would have been better if Al Capone had gone to jail for murder rather than tax evasion, but at least he went to jail for something.

And in my view of how real-world karma works, the two things aren’t unrelated. If you think the rules against murder don’t apply to you, it shouldn’t shock anybody that you think the rules against paying taxes don’t apply either.

When you step off the path roped-off and well-lit by clear rules and take your chances in the jungle, making your own rules on the fly, you take your chances with whatever the jungle can throw at you. Maybe a tiger will get you. Maybe you’ll starve. Maybe you’ll get some disease. Or, maybe another traveler making his own morality will beat you at your own game.

You can cry, “No fair!” all you like. The thing is, “fair” has nothing to do with it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.