Hi,

There’s been a lot of commentary about two very different sociopaths: Jordan Neely and Donald Trump. I’m going to join in, but offer something different.

So let’s start with Friedrich Hayek. He considered common law superior to statutory law. Common law is just a fancy term for judge-made law. The benefit of judge-made law—historically—is that it was generated over time by specific cases, involving flesh-and-blood plaintiffs and defendants who were trying to work out real-world problems. The problem with statutory law—i.e. legislation from a central authority—is that it’s too abstract, too top-down, and too broad to account for all the complexity of real life. Judges built on a foundation of precedent by building on the rulings of judges before them and were constrained by a need to resolve the specific dispute in front of them as narrowly and efficiently as possible.

Hayek also preferred common law because he believed that law was largely a thing to be discovered through investigation and the application of reason, not constructed in the air of abstraction. Judges were law-discoverers, legislators (and monarchs) were lawmakers. Hayek wrote:

Until the discovery of Aristotle’s Politics in the thirteenth century and the reception of Justinian’s code in the fifteenth… Western Europe passed through… [an] epoch of nearly a thousand years when law was… regarded as something given independently of human will, something to be discovered, not made, and when the conception that law could be deliberately made or altered seemed almost sacrilegious.

Now, one can overdo all this. And I need to pull out of this rabbit hole. But the important distinction I want readers to take away from this is that when it comes to the law in general, and crime and punishment in particular, the facts matter more than the ideas.

Say you’ve been arrested for a heinous murder you didn’t commit. You might nod along to every law-and-order firebrand on TV: “Society cannot let wanton disregard for life go unpunished!” “The death of this innocent child is a shock to the conscience and the state must bring swift justice!” But none of those sentiments and pieties outweigh your response: “Yeah, but I didn’t do it!” The idea of justice is hugely important, but justice is just a word when disconnected from the facts.

In many illiberal societies—and not just pre-Enlightenment ones—“but I didn’t do it” is often not enough. Ancient kings and modern commissars alike believed that guilt was transferable to categories of people. It didn’t matter to Lenin what the specific kulaks he hanged did or didn’t do. Kulaks as a category were guilty. Tribal warfare, modern and ancient, is built on this logic. “They killed one of ours, so we’ll kill one of theirs.” Guilt is transitive. You don’t have to kill the specific person who murdered a member of your tribe. They’re all interchangeable.

This sort of thinking is deeply ingrained in human nature and it’s everywhere today.

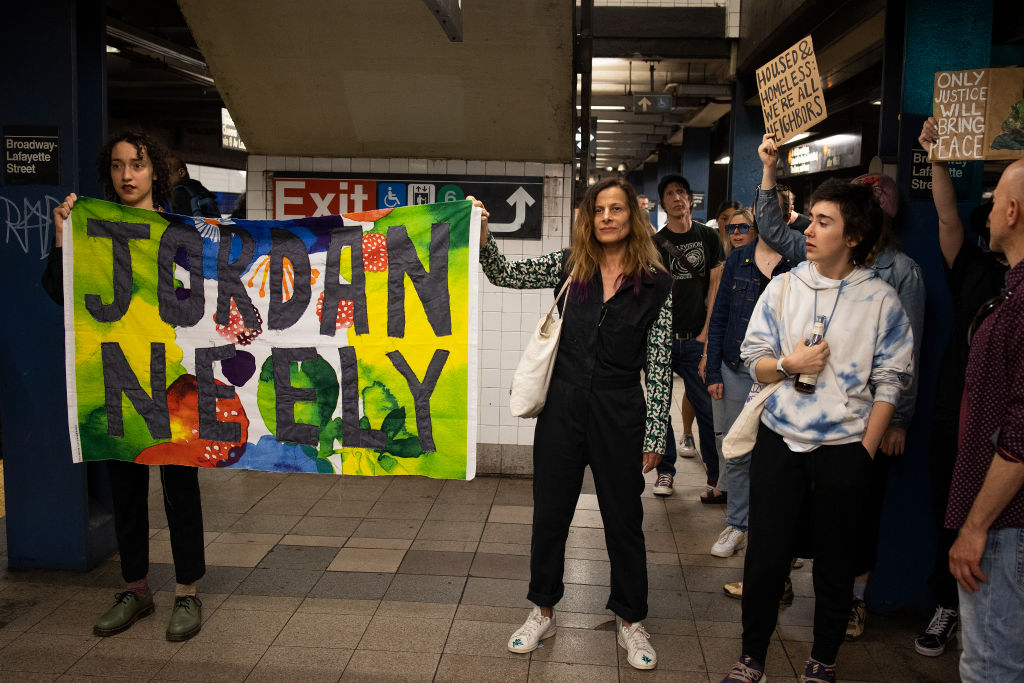

The tragedy of Jordan Neely.

Jordan Neely, a mentally ill homeless man, was killed last week on a New York City subway.

Neely’s death was tragic, but so was his life.

Neely had a history of mental illness, drug abuse and trauma. His mother was murdered by her boyfriend when he was 14. They found her body stuffed in a suitcase. He’d been arrested 40 times in just the last few years and was on the city’s “Top 50” list of homeless people most in need of intervention because they might be a threat to themselves or others. In 2021, he punched a 67-year-old woman in the face, breaking her nose and an orbital bone. He was sentenced to 15 months in a drug rehab facility. He fled in less than two weeks. There was a warrant for his arrest. Needless to say, the authorities did not prioritize apprehending this man on the “Top 50” list—despite the fact he had more than a few interactions with police and social workers. Last week, he was on the subway, shouting all manner of things and behaving in an allegedly threatening manner. Daniel Penny, a former Marine, put him in a chokehold for 15 minutes, and he died.

Neely did not deserve to die. And so far, there’s no plausible evidence that Penny intended to kill him. If that was the goal, there are faster ways for a Marine to kill a man. But that doesn’t mean Penny was in the right to maintain that chokehold for as long as he did. Unintentional homicide is bad enough. It certainly sounds like the police on the scene believed this was an unintentional and tragic accident, as they interviewed Penny and let him go—to the outrage of many.

Perhaps that was a mistake, perhaps not. The justice system is trying to determine that. And while I worry about criminal justice decisions made by politicians caving to popular pressure, I’m in no position to gainsay the process.

But it’s clear to me that Neely was not “murdered for being homeless” or “murdered for being black,” and it’s grotesque to confidently claim otherwise. If Penny wanted to kill homeless people, he had no shortage of more docile potential victims—black and white—to prey upon. Penny, rightly or wrongly, reacted to specific conditions initiated by a specific person, saying and doing specific things. Penny’s reaction may or may not be criminal based on his specific state of mind and his specific actions.

But to listen to “debate” about this tragic incident, you’d think this was an allegory written by modern day John Bunyans. In Bunyan’s foundational allegorical novel, Pilgrim’s Progress, all of the characters represent grand abstract categories. In Penny’s Perfidy, Daniel Penny represents everything from “sanism”(no, really) to “racism” (of course) to the “systemic violence of the state”:

Make no mistake; a white man lynched Neely because of his Blackness. White supremacy allows white people to function as extensions of settler-colonial state power. Neely was Black, so that was enough reason to lynch him rather than help him. It was enough for some bystanders to watch without intervention.

I’m not going to dwell much on this because I think its detachment from the facts as we know them—aka reality—speaks for itself.

Among the many galling things about this collective response, the most relevant here is that those claiming to be the most offended by Neely’s death are the ones commodifying his life. Commodities are interchangeable. A barrel of oil is valued like any other barrel of similar oil. For these people, Neely is a plug-and-play homeless black guy, interchangeable with any other. And of course, Penny is deprived of any specific humanity and rendered a generic white man, representing all white men.

But there is a sense in which this is state-sanctioned violence. I do not mean the decision by the police not to arrest Penny. I mean the collective decisions of the state and the city of New York to turn a blind eye to people who are dangerous to themselves and others in the name of “compassion.” If the police arrested Neely for fleeing rehab, or if social workers checked him into a hospital—as they should have—he’d be alive today. If Neely died of a drug overdose or from jumping in front of a train car, we’d never have heard of him, because Jordan Neelys die every day in New York City, and not because “late capitalist” New York—or America—doesn’t spend money on homelessness and the mentally ill. Billions are spent on these problems. Or, rather, billions are spent on the supposed problem solvers.

When my brother struggled with drugs and alcohol, my father was constantly worried that “something” terrible would happen to him. That “something” was a many-faced demon in my dad’s imagination—drug overdoses, getting murdered, getting arrested, contracting AIDS in jail, etc. That demon was waiting for Neely. He was on the demon’s “Top 50” list and “the system” knew it. But solely because it took a form superficially congenial to the social justice term paper rhetoric that defines the AOC left, they’re outraged. That outrage renders Neely a prop, not a tragic individual who spent years pressing his luck with a system that sees such troubled, often dangerous human beings as interchangeable commodities. Such thinking isn’t a product of capitalism, but of bureaucratic progressivism.

The tragedy of Donald Trump.

Donald Trump is, in almost literary fashion, the complete opposite of Jordan Neely. Of course, opposites are not as different as the word sometimes implies. Apples and oranges are both round fruits that people eat. Hot and cold are both temperatures. Night and day are different phases of the same cycle.

Donald Trump is a very successful sociopath. I feel guilty about using the word sociopath, but my guilt is reserved for Jordan Neely. His tantrums and threats were driven by hunger, by trauma, by mental illness, and by exhaustion with a system that ground him up. Donald Trump’s tantrums and threats stem entirely from a narcissistic grandiosity and sense of entitlement only possible for someone who has made a lifetime of immoral choices and has either come out the better for it or simply paid no discernable price. As Tim Carney wrote yesterday, “Today’s sexual abuse and defamation verdicts in Trump’s civil trial might be the first time he’s paid any serious price for living his life with total disregard for morality or for other people.”

Whatever you think of the merits of the trial and the verdict, it’s nonetheless obvious that he spent a lifetime preying on women. Do not bring any of that “what about Bill Clinton?” crap to me. I have three decades of consistency on such matters. But just so you know: If you ask, “What about Bill Clinton?” you are conceding that what Clinton did was bad. No legitimate moral code can hold that the allegations of Bill Clinton’s predations were bad but Trump’s are forgivable. Moreover, there’s more corroborating evidence arrayed against Trump than Clinton.

When the Access Hollywood tape came out, Trump reluctantly apologized for it in order to “reassure” Republicans. He later claimed that he thought the tape was a fake, which, if true, would make his apology cowardly. But in the Carroll case, he stood by his comments. He said it was true that “stars” like him could assault women for the last “million years”—“unfortunately or fortunately.” His proudest defense against the charges is that he wouldn’t rape E. Jean Carroll because, “She’s not my type.” At least rhetorically, he’s suggesting rape is understandable for stars if the victim is really hot.

But I should close the circle. There are many “defenses” of Trump that aren’t even defenses, they’re just rationalizations of power worship. But one of the most common takes the form of, “If they can do this to Trump, they can do this to you,” or, “they’re not coming after Trump, they’re coming after you and he’s just in their way.”

This is tribal logic kicking in again. And that’s the tragedy of Donald Trump. Barring some last-minute conversion, his soul is lost. But the compulsion to defend Trump is doing damage to the souls of his defenders.

They can’t come at you for trying to steal an election because you didn’t try to steal an election. They can’t come at you for business fraud, paying off a porn star, or assaulting a woman in a department store because you didn’t do any of those things. There’s an entire industry dedicated to turning Trump into a symbol and his travails into some grand allegory or morality tale that uses his specific misdeeds as plot devices. This is what the supposedly “opposite” hardcore anti-Trump and pro-Trump political factions have in common. (Admittedly, many otherwise decent and sane Republicans have a maddening habit of making the case easier for the anti-Trump faction by dismissing or downplaying Trump’s corruption.) When we turn Trump into some grand abstraction, we make “ideas” more important than the actual facts. And the actual fact is that Trump only cares about any ideas if they validate his narcissism or enable his personal gratification.

Jordan Neely lived a miserable life because we are too deferential to powerlessness. We wrap the powerless in righteous concepts of victimhood and use them as a political weapon against “the system.” We use the powerless as props for some larger abstract goal of social justice. Donald Trump has lived a lavish, grotesquely selfish, and corrupt life because we are too deferential to power and celebrity (or “stars”). The specifics get washed away into the undertow of various preferred narratives.

The common law approach—which utterly failed Neely but has, finally, started to catch up with Trump—declares such narratives inadmissible. What, specifically, did this specific person do? Why did he do it? What evidence is there to support or refute his explanation? Questions of “what will this mean?” for one side, or tribe, are irrelevant. That’s why Trump lost all of his dozens of substantive legal challenges to the election—because in a court of law the facts matter more than the bogus ideas peddled at Four Seasons Landscaping or Mar-a-Lago.

It’s true that in the past, powerful people—Trumpian “stars”—could get away with all kinds of depravity. Through a long process of discovery, the law—biblical law first, common law after—recognized that such depravities were unacceptable for the powerful and powerless alike. We’ve never perfected this ideal in practice, but we’ve gotten better. The rationalizations of Trump’s behavior—and to a certain extent Neely’s—are a reactionary rejection of this monumental human project that says individuals are only responsible for their own actions—and that this responsibility cannot be waived based on status.

I’ve written a lot about how frustrated I get when legalisms intrude on questions of politics and morality. But I’ll say this for the legal approach: It thinks the truth matters more than the legends.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.