Happy Thursday. On this day 77 years ago, Soviet forces reached the Auschwitz concentration camp, liberating thousands of Jewish prisoners who had not already been evacuated by the Nazis and forced into a death march.

On this Holocaust Remembrance Day, take a moment to commemorate the millions upon millions of victims of Nazi hatred and reflect on the societal forces that allowed such atrocities to persist.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

NBC News reported Wednesday that Justice Stephen Breyer, 83, will retire from the Supreme Court at the end of the current term, paving the way for President Joe Biden to appoint a younger successor to the court. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer declared Biden’s nominee will “receive a prompt hearing” and be confirmed “with all deliberate speed.”

-

Secretary of State Antony Blinken told reporters on Wednesday the Biden administration had delivered a written response to Moscow that responds to Russia’s recent demands surrounding NATO and Ukraine. “We’re open to dialogue, we prefer diplomacy, and we’re prepared to move forward where there is the possibility of communication and cooperation if Russia de-escalates its aggression toward Ukraine, stops the inflammatory rhetoric, and approaches discussions about the future of security in Europe in a spirit of reciprocity,” Blinken said.

-

The United States’ embassy in Ukraine sent a message to American citizens in the country on Wednesday urging them to “consider departing now” using commercial transportation due the “increased threat of Russian military action.”

-

The Federal Reserve concluded its January Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) meeting on Wednesday, with Chair Jerome Powell announcing the central bank remains on track to wrap up its monthly asset purchases in March, when it will likely begin raising interest rates.

-

The Census Bureau reported yesterday the United States’ international trade deficit in goods reached a record high in December, increasing 3 percent month-over-month to cross the $100 billion monthly threshold—and $1 trillion annual threshold—for the first time.

For months, we’ve been hearing about the “Great Resignation” sweeping across the country as workers—emboldened by labor shortages and higher wages—quit their jobs at record rates in search of greener pastures. Yesterday, the phenomenon hit the highest court in the land.

Just before noon on Wednesday, NBC News’ Pete Williams went live with a story that, within minutes, had turned Washington on its head: Justice Stephen Breyer, the oldest member of the Supreme Court, plans to step down at the end of the court’s current term. The 83-year-old justice has yet to publicly confirm the news—which was attributed to “people familiar with his thinking”—but CNN reported he will do so at a White House event with President Biden later today.

Any change to the composition of the court is inherently big news given its limited size and its current centrality to our politics, but Breyer’s retirement is hardly unexpected. Having sat on the bench for nearly 28 years, Breyer could only guarantee he’d be succeeded by a philosophically aligned justice if he stepped down before the 2022 midterm elections. Progressive activists—still reeling from Republicans’ confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to replace the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020—had been calling on Breyer to take this step for more than a year.

“It is a relief that President Biden will get the opportunity to choose the next justice on the Supreme Court while the Senate is in Democratic hands,” said Brian Fallon, executive director of Demand Justice, adding that Breyer’s decision came “not a moment too soon.” In April 2021, Fallon’s judicial advocacy group rented a billboard truck to circle the Supreme Court while displaying “Breyer, Retire” in big, bold lettering.

For months, Breyer bristled at these calls. Last July, he told CNN he was enjoying his role as the senior liberal justice and hadn’t yet decided when to step down. One month later, he disclosed to The New York Times that, although he didn’t think he would stay on the bench until he died, he was struggling to make up his mind on retirement. But he admitted concerns about a successor reversing his legacy would “inevitably be in the psychology.”

There were some conflicting reports yesterday as to whether Breyer intended the news to leak when it did—he reportedly told the White House of his plans last week—but by all accounts, the decision to retire was ultimately his alone. “He’d fully made the decision, never felt pressured by this,” said Fox News chief legal correspondent Shannon Bream. “It was going to happen very, very soon, but not today.”

Within minutes of the news breaking, the Biden administration sought to dispel any notions it had been involved in Breyer’s deliberations. “It has always been the decision of any Supreme Court Justice if and when they decide to retire, and how they want to announce it, and that remains the case today,” press secretary Jen Psaki tweeted. Biden later told reporters he wouldn’t talk about the news until Breyer announced it himself.

But the White House’s reticence did not carry over to Capitol Hill, where Democrats began gearing up for what will likely be an anticlimactic confirmation process. “President Biden’s nominee will receive a prompt hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee, and will be considered and confirmed by the full United States Senate with all deliberate speed,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said. Sen. Patty Murray, a Democrat from Washington, was out with a statement almost immediately calling on Biden to stand by his February 2020 campaign pledge to nominate the first black woman to the Supreme Court, which Psaki later confirmed he would do.

Despite approximately 11,430 jokes being made to this effect yesterday, Biden is unlikely to foist Kamala Harris upon the Supreme Court as a means of ridding himself of her lagging approval numbers ahead of a 2024 campaign. Instead, he will likely be picking between DC Circuit Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, and South Carolina U.S. District Judge J. Michelle Childs.

Jackson, who clerked for Breyer a little over two decades ago, served on the U.S. Sentencing Commission from 2010 to 2014 and spent eight years as a district court judge before Biden elevated her last summer to succeed Merrick Garland on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. (Fun fact: Jackson is married to the twin brother of former House Speaker Paul Ryan’s brother-in-law, and the Wisconsin Republican testified on her behalf in a 2012 confirmation hearing.) Kruger, meanwhile, clerked for the late Justice John Paul Stevens before working in the U.S. Solicitor General’s office, and was nominated to California’s Supreme Court in 2014 at the age of 38. Childs was a circuit court judge in South Carolina before then-President Barack Obama appointed her to the state’s federal district court in 2010.

Any of these candidates, if selected, should be able to work her way through the confirmation process with relative ease. Senate Democrats triggered the body’s “nuclear option” in 2013 to do away with the filibuster for most presidential nominees, and—in an effort to confirm Neil Gorsuch—Senate Republicans did the same for Supreme Court nominees in 2017. As a result, Biden’s pick will require the support of just 50 senators—plus Harris’ tie-breaking vote—to be seated on the high court.

Because Democrats have had such a difficult time getting to 50 votes in recent months, you’d be forgiven for assuming Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema could be a thorn in Biden’s side here. With such a thin majority, one single Democratic defector could doom the potential justice. But don’t count on it: The two moderates have voted for every Biden judicial nominee thus far, including Jackson last June. Republican Sens. Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and Lindsey Graham voted in favor of Jackson’s confirmation as well, and Collins and Graham supported both of Obama’s Supreme Court nominees, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

In a recent analysis, political scientists Lee Epstein, Andrew Martin, and Kevin Quinn estimated Kruger’s jurisprudence to be more or less in line with Breyer’s, while Jackson and Childs were considered closer to the center. “Because all the potential nominees are ideologically fairly close to Breyer and Kagan, none are well-positioned (at least in the short term) to move the Court’s center of power to the left,” they write. “The implication, in turn, is that there are no implications of Breyer’s departure.”

The GOP reaction to Wednesday’s news was relatively muted, in part because swapping Breyer out for another liberal justice does nothing to change the court’s current 6-3 conservative majority and in part because there’s little the party can do to stop a confirmation even if it wanted to. “If all Democrats hang together—which I expect they will—they have the power to replace Justice Breyer in 2022 without one Republican vote in support,” Graham said yesterday.

The details remain up in the air, but Biden reportedly plans to unveil his nominee shortly after Breyer makes his retirement official. Not only would the quick turnaround change the subject from a string of legislative defeats and pump some energy into an increasingly demoralized Democratic base, but it would allow the Senate to jumpstart the confirmation process, which—if all goes according to plan—would wrap up before the current Supreme Court term ends in late June or early July. The new justice wouldn’t be sworn in until Breyer officially retires.

“We want to be deliberate,” Schumer said yesterday. “We want to move quickly. We want to get this done as soon as possible.”

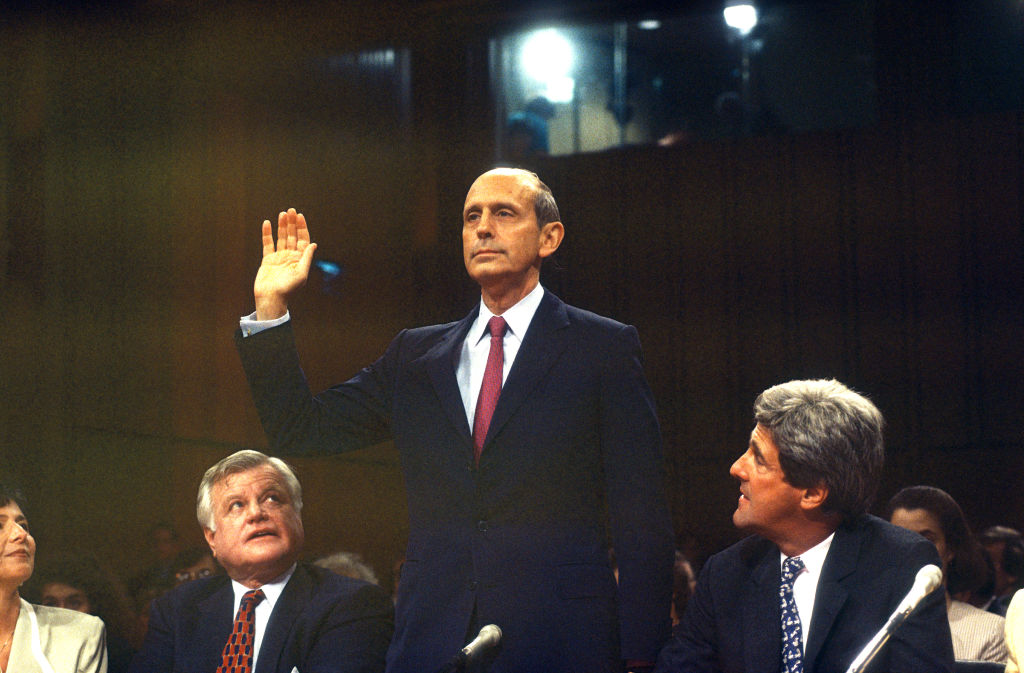

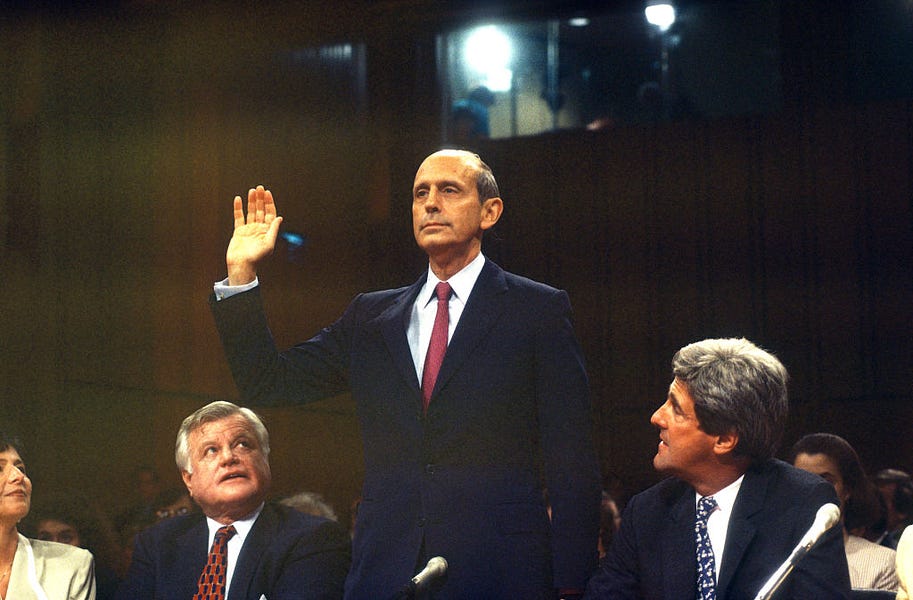

When Breyer steps down from the court in a few months—likely soon after it issues a ruling in the landmark abortion case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—he will take with him the last vestiges of a different era of liberal judicial tradition. Nominated by President Bill Clinton in May 1994 and confirmed by the Senate in an 87-to-9 vote two months later, Breyer—who was the least well-known justice in a recent Marquette Law School poll—spent his 27-plus years on the bench as a reliably center-left vote who relied on long-winded hypothetical questions in oral arguments, sought to build consensus when possible, and cared deeply about the institution where he served.

“A judge’s loyalty is to the rule of law, not the political party that helped to secure his or her appointment,” he wrote in his latest book, which warned of eroding the Supreme Court’s legitimacy through overtly partisan reforms. Last April, he delivered a speech at Harvard Law School encouraging progressive proponents of packing the court to “think long and hard” about making that structural change.

“When I or others dissent, naturally I think the majority is wrong, and sometimes I think they are very wrong,” Breyer said. “But discussion of institutional change should include discussion of certain background matters, such as the trust that the court has gradually built, the long period of time needed to build that trust, the importance of that trust in a nation that values—indeed depends upon—a rule of law.”

This line of reasoning from Breyer was on display last month in the Dobbs v. Jackson oral argument. “The problem with a super case like this, the rare case, the watershed case, where people are really opposed on both sides and they really fight each other, is they’re going to be ready to say, ‘No, you’re just political, you’re just politicians,’” he said. “And that’s what kills us as an American institution.”

Worth Your Time

-

Tyler Cowen’s latest Bloomberg column focuses on recency bias, humans’ tendency to overweight events of the recent past and assume current trends will continue. “For instance, starting in 2008 the U.S. Federal Reserve increased the money supply sharply, and the rate of price inflation did not rise correspondingly. One result of this recent episode of expansionary monetary policy is that America became less vigilant about inflation—and it is now living with the consequences,” he writes. “The plan for overcoming recency bias is pretty straightforward. Spend less time scrolling through news sites and more time reading books and non-news sites about how your issues of concern have played out in the distant past. If you are young, spend more time talking to older people about what things were like when they were growing up. If you had applied those techniques, Russia’s interest in taking over more parts of Ukraine would not be very surprising.”

-

In The Washington Post, former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul recounts a 2011 meeting between Vladimir Putin and then-Vice President Joe Biden. “At one point, Putin told Biden (and I’m paraphrasing from memory), ‘You look at us and you see our skin and then assume we think like you. But we don’t,’” McFaul writes, explaining why a realist analytical framework doesn’t necessarily explain Russia’s behavior. “[Putin] has his own analytic framework, his own ideas and his own ideology—only some of which comport with Western rational realism.” Because the Russian president believes the West unfairly dictated the terms of peace at the Cold War’s end and that geopolitics is a never-ending struggle between democracy and autocracy, he won’t be satiated even by a pledge to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO. “He will press on to undo the liberal international order for as long as he remains in power,” McFaul argues. “Normalizing annexation, denying sovereignty to neighbors, undermining liberal ideas and democratic societies, and dissolving NATO are future goals.”

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

On Wednesday’s Dispatch Podcast, Sarah, Steve, Jonah, and David discuss the worsening situation in Ukraine before turning to two issues not getting enough attention in the lead up to the midterms: immigration and crime.

-

Jonah’s Wednesday G-File (🔒) focuses on Breyer’s retirement and Biden’s pledge to appoint a black woman as his successor. “The African American women in contention may be eminently qualified,” he writes. But by preemptively limiting himself to one group of people, Jonah argues Biden has attached a “stigma” to the eventual appointee, even if it’s undeserved. “All of the likely nominees would be in a better position today if Biden hadn’t made the promise in the first place.”

-

In yesterday’s Capitolism (🔒), Scott Lincicome checked in on how the Biden administration has handled trade policy thus far. “No one actually paying attention to Biden’s long history, the longstanding protectionism of congressional Democrats (especially those in charge), and the Biden campaign’s clear rhetoric expected much on trade from this administration,” he writes. “So it’s just that much more disappointing that he couldn’t even clear our very low bar.”

Let Us Know

In Breyer’s aforementioned Harvard Law School speech, he contends that, while the American public generally views Supreme Court justices as “primarily political officials,” the justices themselves tend to think their differences “reflect not politics but jurisprudential differences.” He added: “We all try to avoid deciding a case on the basis of ideology rather than law.”

Is he right?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@lawsonreports), Audrey Fahlberg (@AudreyFahlberg), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), Harvest Prude (@HarvestPrude), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.