Happy Monday. We hope your weekend was great (as possible). Lots to get to today. Let’s do the news.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

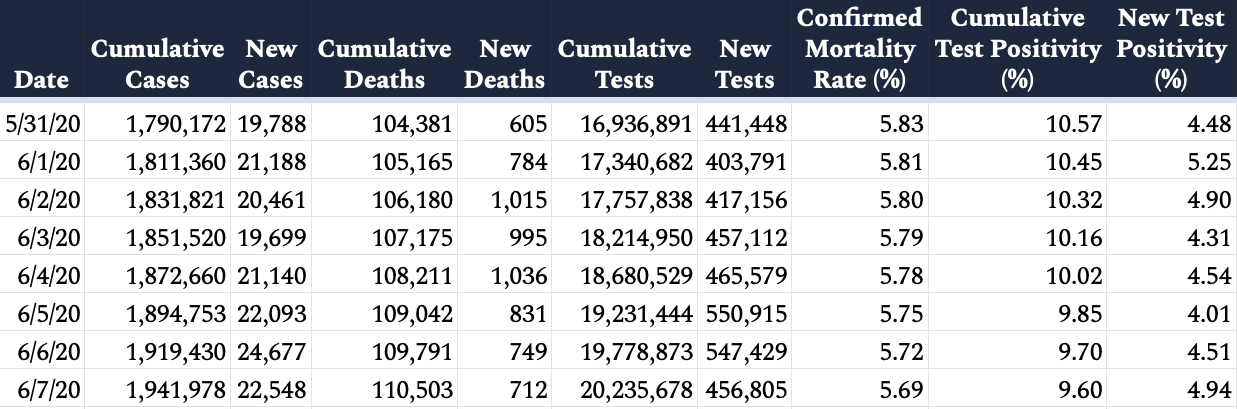

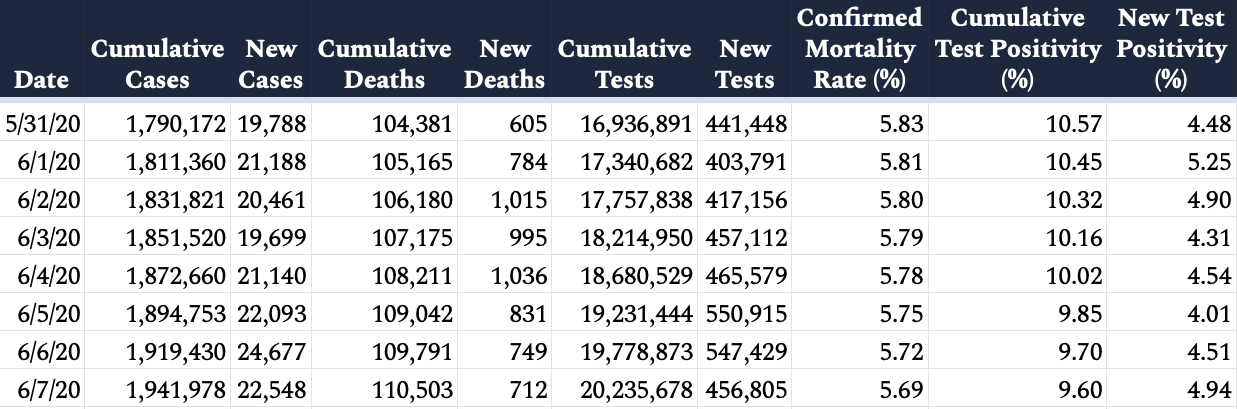

As of Sunday night, 1,941,978 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States (an increase of 22,548 from yesterday) and 110,503 deaths have been attributed to the virus (an increase of 712 from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 5.7 percent (the true mortality rate is likely much lower, between 0.4 percent and 1.4 percent, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 20,235,678 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (456,805 conducted since yesterday), 9.6 percent have come back positive.

-

Friday’s jobs report beat expectations. Rather than increase to near 20 percent, as many economists worried, the unemployment rate actually declined in May, settling in at 13.3 percent as economic activity gradually picks up.

-

Nine members of Minneapolis’s City Council—a veto-proof majority—announced their intention to “disband” the city’s police department, vowing to replace it with a “new model of public safety.” Details of the proposal remain fuzzy, however. “The idea of having no police department is certainly not in the short term,” City Council President Lisa Bender said.

-

On Friday, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said the organization was “wrong in not listening to players” like Colin Kaepernick who protested racism and police brutality. Goodell’s apology was posted a day after the release of a different video in which a number of prominent black football players called on the NFL to take a stronger stance against racism.

-

At least a dozen Texas county GOP chairs have shared bigoted conspiracies about the death of George Floyd and the protests that have followed, including claims that Floyd’s death was staged to hurt Donald Trump’s re-election prospects, according to a report in the Texas Tribune. Gov. Greg Abbott and some other state Republican leaders have denounced the claims.

-

A new NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll sheds some light on the national mood: Eight out of 10 American voters believe that “things are out of control in the nation.” Meanwhile, 59 percent are more concerned about police brutality and George Floyd’s death than they are about protests becoming violent, compared with 27 percent who say the opposite.

What Does ‘Defund the Police’ Mean?

On Saturday, protestors in D.C. added new words to the “Black Lives Matter” mural painted on 16th Street just north of the White House: Defund the Police.

So, what does it mean? The plain language of the proposal is breathtakingly radical. But many of its advocates have adopted a familiar line to downplay what would be on its face a rather extreme proposal: take us seriously, not literally. Some supporters want to increase the budgets of other community programs paid for out of money currently directed toward police budgets. Others want to replace core police functions with social workers and community representatives. And others still have described it as a larger project of restorative justice that would draw on “pre modern conceptions of conflict resolution—such as peace circles—as an alternative to police and prisons.”

By Sunday, however, many Democratic leaders were distancing themselves from the slogan. Rep. Karen Bass, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus who is set to announce legislation for police reform this coming week, said that she didn’t “believe you should be disbanding police departments” but also said that “part of the movement around defunding is really about how we spend resources in our country, and I think far more resources need to be spent in communities to address a number of problems.” Sen. Cory Booker said that “it’s not a slogan I’ll use,” but added that “we are overpoliced as a society … we are investing in police which is not solving problems, but making them worse.”

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey was booed and told to “go home” after he declined to support the idea, and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio echoed the same sentiment, saying “I do not believe it’s a good idea to reduce the budget of the agency that’s here to keep us safe.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, on the other hand, is advocating for a “reduction of our NYPD budget.” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said the city is considering cutting “$100 million to $150 million from its nearly $2 billion annual police budget to redirect to black communities.” And Minneapolis City Council President Lisa Bender told CNN that, despite the mayor’s reluctance, the council intend to “dismantl[e] policing as we know it in the city of Minneapolis and to rebuild with our community a new model of public safety that actually keeps our community safe.”

Joe Biden has yet to address the issue publicly, but his website includes a proposal in the opposite direction: Increasing funding for police departments “for the hiring of additional police officers and for training on how to undertake a community policing approach.”

So what would a more extreme version of “defunding the police” look like?

Few concrete examples of defunding programs exist, but a unique grassroots movement out of Durham, N.C., provides a possible blueprint for the diversion of police department capital to alternative community programs. Beyond Policing, a coalition of young activists formed to provide safety and wellness services outside of law enforcement, has gained significant traction in the Durham community over the past four years. The group formed in 2016 in opposition to the construction of a $70 million police headquarters and has since grown into a powerful lobbying force. Durham Beyond Policing has played a decisive role in the election of the current City Council, district attorney, sheriff, and three judges, all of whom support comprehensive law enforcement and incarceration reform. Last June, members of the organization successfully lobbied City Council members to reject the Durham Police Department’s request for $1.2 million to hire 18 new patrol officers.

To Durham’s mayor Pro Tempore Jillian Johnson, however, there is still work to be done to re-examine the city’s approach to public safety. In an interview with NPR, Johnson made an impassioned case for long-term investment in the city’s residents:

Our best chance for building a safety solution that puts people first, that puts communities first, that takes care of people rather than criminalizes, incarcerates and punishes them is by shifting resources that we use for policing into other systems, alternative systems, alternative institutions rather than the institutions that we know are causing us harm.

Johnson rejects proposals to reform the existing policing system as viable solutions, but next week House Speaker Nancy Pelosi will introduce a bill to do just that. House Democrats’ police reform legislation is expected to include a ban on chokeholds and more accountability for police departments, including “the review process for misconduct, demilitarizing the police force, requirements and resources for body cameras, the overhaul of police training, and making the use of deadly force a last resort.”

What Hath Qualified Immunity Wrought

As elected officials seek to turn protests into policing reforms, another frequently-mentioned proposal is ending qualified immunity.

The debate over qualified immunity reached Capitol Hill last Sunday with Rep. Ayanna Pressley and Rep. Justin Amash’s proposed legislation to abolish the legal doctrine entirely. At least 38 Democratic members of Congress, as well as six Democratic and independent senators, have now joined the call to end qualified immunity for state and local officials.

So, what exactly is qualified immunity and why is it controversial?

In essence, qualified immunity—as opposed to the absolute immunity given to legislators, judges, and prosecutors—is the legal principle responsible for shielding state and local officials like police, school administrators, and prison guards from civil liability when they violate a person’s civil rights. Critics of this selective protection argue there is no workable mechanism by which to sue and receive compensation for the violation of your civil and constitutional rights by these officials and in particular law enforcement. But this wasn’t always the case.

In 1871, Congress passed the Third Enforcement Act, now most often referred to as Section 1983 of the U.S. Code, which states that individuals whose rights have been infringed by government officials are entitled to legal recourse. According to Clark Neily, vice president for criminal justice at the Cato Institute, Congress deliberately chose to ignore the previous common law defense, which held that an official was immune from liability if he acted in good faith, and instead wanted a victim to receive compensation for the violation of his or her civil rights no matter what. Under the law as it was passed by Congress, he argues, any breach of one’s civil rights was intended to lead to financial redress in civil court, regardless of whether the official knew they were doing anything wrong at the time.

To those who want to get rid of the qualified immunity doctrine, the 1967 Supreme Court decision, Pierson v. Ray, which established qualified immunity, is a prime example of the dangers of judicial policymaking. William Baude, a law professor at the University of Chicago who has written extensively about qualified immunity, argues the decision was misguided and strayed outside both the text and the intent of the original law.

“Pierson took an element of the common law (“good faith”) and glued it on to a claim that was based in the Constitution. This was one of the most consequential misinterpretations of the statute, although it was made worse by the Court’s subsequent expansions of the doctrine.”

Most notable of those subsequent expansions came 15 years later in another Supreme Court case, Harlow v. Fitzgerald, which laid out the current standard for qualified immunity. Rather than receiving immunity if the official acted in “good faith”—as established by Pierson—state and local officials were now exempt from liability unless it could be proved not only that the victim’s rights had been violated but that those rights had been “clearly established” at the time. This increased the burden on the plaintiff, making it exponentially more difficult to win a civil case against law enforcement.

Opponents of qualified immunity have two options. The Supreme Court established the current doctrine of qualified immunity, and therefore, it could also get rid of it or, more likely, replace it with a more narrow standard. Right now, there are nine pending qualified immunity-related cases before the Supreme Court, which the court could choose to hear next term. Congress could also abolish it. Given the current surge in calls for police reform, either of these scenarios are well within the realm of possibility.

For more on qualified immunity, on the site today Brad Polumbo looks at Amash and Pressley’s proposed legislation and points out that experts believe qualified immunity gives police “a sense of impunity that increases recklessness and abuse.”

A Growing Chorus of Anti-Trump Republicans

Colin Powell—retired four-star Army general and former national security adviser, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and secretary of state—served under Reagan and both both Bushes but he hasn’t supported a Republican candidate for the nation’s highest office since 2004. That will not change in November.

“I couldn’t vote for him in [2016], and I certainly cannot in any way support President Trump this year,” Powell told CNN’s Jake Tapper on Sunday. That he is supporting Joe Biden—who he has worked with “for 35, 40 years”—should be no great surprise.

But the news comes just days after Gen. James Mattis’ denunciation of the president, and Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s subsequent waffling. Over the weekend, Jonathan Martin of the New York Times reported on the ranks of prominent Republicans either not supporting or on the fence about Trump’s re-election bid. Former President George W. Bush, Sen. Mitt Romney, and Cindy McCain are in the former camp. Jeb Bush, Paul Ryan, John Boehner, and former Trump Chief of Staff John Kelly are in the latter.

Trump won the 2016 Republican primary, of course, in part by running against these exact people and the politics they stand for. But it’s not just the skeptics of yesteryear who have qualms with the president. As we’ve reported before, many GOP elected officials “detest the president, disapprove of his conduct, and worry about the consequences of his presidency.”

Democratic Sen. Chris Coons told Martin he’s had “five conversations with [Republican] senators who tell me they are really struggling with supporting Trump.” Former Sen. Claire McCaskill said, “It’s easier to count the ones who are definitely voting for Trump.” Martin himself had a conversation with a GOP senator who is publicly supporting the president’s reelection, but said he might prefer a Biden victory—so long as Republicans keep the senate.

“There’s a lot of prominent Rs and national security types who are wrestling w[ith] how and when to say they won’t vote for Trump and whether to be openly for Biden,” Martin tweeted. “And that decision-making got accelerated this week.”

Worth Your Time

-

Coronavirus doesn’t discriminate based on one’s political preferences. But in our increasingly tribal political culture, the virus has become a partisan football. As Yuval Levin writes in an article for The New Atlantis, our political and cultural leaders have insisted on politicizing every aspect of the pandemic. Both partisan tribes are guilty of this: the right’s senseless resistance to mask-wearing and the left’s inconsistency on the lockdown in light of the recent anti-police brutality protests are both symptoms of our persistent tribalism. And in turn, Levin writes, this partisan “attitude inevitably makes it much harder for the public to assess scientific claims about the pandemic through anything other than a political lens.” If we are to defeat the coronavirus in the coming months, we need to be capable of seeing beyond our tribal commitments rather than maintaining that “there are left-wing and right-wing views on whether to wear masks, whether particular drugs are effective, or how to think about social distancing.”

-

Rep. Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin, a former Marine with two masters degrees in national security and a PhD in International Relations, argues in the Wall Street Journal that we’re in a cold war with China. It’s different than the Cold War, he says—“Communist China is a more formidable economic rival to the U.S. than Soviet Russia ever was, and America and China are more deeply connected than the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. were”—but we can still draw lessons from our long standoff with the Soviet Union. “Holding the line and deterring war will require more investments in hard power,” Gallagher writes. “But America must also compete in the ‘gray zone,’ leveraging allies and liberal values to wage ideological warfare and ensure countries don’t embrace the Communist Party’s authoritarian model.”

-

Gen. CQ Brown Jr., the commander of the Pacific Air Forces, has released an emotional video about the challenges of being black in the military and shares other thoughts he’s had in the wake of George Floyd’s death. “I’m thinking about wearing the same flight suit, with the same wings on my chest as my peers, and then being questioned by another military member, ‘Are you a pilot?’”

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

If you’re a paying member who tuned into last week’s latest Dispatch Live session, you probably remember David’s story about coming to grips with the persistent reality of racism in America when he adopted his youngest daughter from Ethiopia. If you missed David’s story—or want more of his thoughts on the subject—the latest French Press is a must-read.

-

Jonah’s longtime pal Vincent Cannato returns to the Remnant for a second time to debunk a wide range of popular history-related canards (reminder: history does not, in fact, repeat itself). Plus, in Jonah’s solo Saturday Ruminant, he talks about some potential problems with the ongoing national protest movements.

-

The latest episode of The Dispatch Podcast features Jane Coaston, a journalist who writes about conservatism and the far-right for Vox. Sarah, Steve and Jane talk about race, police brutality and the worldwide protests over the death of George Floyd, and discuss the unique challenges to policing reform in the United States.

-

Over the weekend, Alec Dent debunked a now-deleted tweet from the former chair of a major Democratic Super-PAC claiming that President Trump mocked “I can’t breathe.” And the latest Fact Check, up on our site today, takes on the president’s erroneous claim that Twitter censored a campaign video.

-

Ever wonder about the intricate politics of the American meat-processing industry? No? Either way, Blake Hurst has you covered. His new article, up on the site today, describes the troubles on the horizon for meat-packers throughout the country—and why those issues should matter to all of us.

Let Us Know

Over the last two weeks, our inaugural crew of Dispatch interns and fellows have come online, freeing your ordinary Morning Dispatchers up to spend more time pursuing their true passion: eating ice cream by the pint while bingeing old episodes of Pawn Stars. How are the new folks doing? (If you can’t tell which parts they wrote, that means it’s working!)

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Nate Hochman (@njhochman), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.