Campaign Quick Hits

For those who took up residence under a Wi-Fi-free rock over the weekend: The president tested positive for COVID-19 and was admitted to Walter Reed Hospital, where we are told by his doctors that he has steadily improved as of Sunday afternoon.

How it may affect the election: It’s still too early to know how voters will react to the president’s diagnosis and treatment (in part because we don’t know how the president will react to his diagnosis and treatment), but my gut says it won’t change things and early indications are consistent with that as well. According to the latest Survey Monkey daily tracking poll, Joe Biden maintains his steady national lead over Trump, 52 percent to 44 percent, and Trump’s job approval remains “underwater but unchanged” at 44 percent. Further, ABC’s latest poll showed “approval for the president’s handling of the pandemic remained steady” at 35 percent. Further evidence that these numbers are unlikely to change is that the partisan divide remains steady across these polls, with nine in 10 Republicans, for example, believing the president will “be able to effectively handle his duties as president if there is a military or national security crisis.”

My own personal focus group: I reached out to a half-dozen Trump voters this weekend from varying parts of the president’s base to see whether anything this week had or could change their votes. One had already voted early and didn’t regret her vote—just a reminder that the election is very much underway. But to a person, not one even considered changing their vote. So while you will see multiple polls showing large majorities who believe “if President Trump had taken coronavirus more seriously, he probably would not have been infected,” that doesn’t mean they are going to change their votes. The one undecided voter I spoke with said she still isn’t sure who she is going to vote for—she doesn’t like Trump’s personality but is concerned about how radical a Biden administration could end up being—but that the news from this weekend didn’t factor into her decision at this point.

Oh, right, there was a debate this week: It’s hard to remember back that far, but the first presidential debate happened less than a week ago. Tevi Troy sent me a fun historical fact: “There have been seven incumbents who have debated in the presidential debates since 1976. Six of those incumbents lost either the first debate or the debates as a whole. Clinton lost no debates and won re-election. The three who lost but then righted the ship after a loss (Obama, Reagan and Bush 43) won re-election. The other three (Ford, Carter, and Bush 41) lost to the challenger.” This, of course, doesn’t mean that those debates changed any votes; it’s just as likely to me that people’s vote preferences colored who they believed won those debates. So while a majority of people across the polls believed Biden won the first debate, more than 90 percent who said “they’d already decided on Trump or Biden planned to stick with their choice.” In a related focus group, these voters indicated that “there’s almost nothing that could change their minds between now and November.” Here was a telling response: “Dartavia P. said she was ‘irritated that [President Trump] kept talking over everybody and that he wouldn’t answer the questions,’ but plans to vote to re-elect him.”

What about the next debates: Assuming the debates continue, viewership will be a big question. About 73 million people tuned in to the first one, which was a 13 percent drop compared with 2016, but is likely due to the increase of people using streaming television services, which are not monitored the same way traditional viewing is tracked. At this point, the biggest purpose of the debate may be to increase turnout. (I know, I know, you’re sick of hearing about turnout from me … but it’s true!) From the last debate, “only 5% of Democrats said they were primarily excited after the debate, compared with 18% of Republicans.” But neither of those numbers is particularly stellar for either candidate at this point.

A billion here, a billion there and pretty soon we’re talking real money: Campaign spending this cycle is on pace nearly to double from four years ago to a projected $11 billion. Not surprisingly, that money isn’t going toward travel and event costs anymore and instead campaigns are spending more of their funds on television and digital advertising. For those interested in campaign finance 10 years after the Citizens United decision, I summarized the best arguments for whether allowing outside groups to spend money independently from campaigns has mattered to our electoral process and what might come next. Check out my write up here.

The Democrats are ruining my experiment: We were finally going to have a large-scale experiment about the efficacy of presidential ground games and door knocking operations. As of last week, the RNC was boasting that it had “knocked on the doors of 19 million voters they believe are likely Trump voters, either talking to the resident or leaving a piece of literature if no one answered” and the Biden team had hit zero. But now, the Democratic campaign is sending “several hundred newly trained volunteers to engage voters across Nevada, Michigan, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania” to contact “voters who are considered difficult to reach by phone.” Then again, if the Biden campaign sticks to these four states, the experiment could get even better because we will have Trump-only states to compare to Trump-Biden states. Lots to learn after 2020 is over!

Two counties to watch: A couple weeks ago, I wrote about the reliably red WOW counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, Washington) around Milwaukee that are always worth watching on election nights. Here are two more counties to add to your list: Hillsborough County, which contains Tampa, Florida; and Lehigh County, which contains Allentown, Pennsylvania.

In 2004, 2008, and 2012, Bush and Obama won Hillsborough County—the fourth largest county in the state—by 8 points. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the county by about 41,000 votes, but lost Florida by about 100,000 votes, or a little more than 1 point. Currently, polling in Hillsborough County shows Biden at 55 percent and Trump at 42 percent, which would be a whopping 13-point spread and would have increased Clinton’s vote share by 35,000 votes in the state. Something similar is happening in Lehigh County. Clinton famously lost Pennsylvania by fewer than 45,000 votes and won the 7th Congressional District, which contains all of Lehigh County, by only 1 point. Currently, Biden is up by 7 points in the latest poll.

Is there such a thing as a sympathy bounce?

Declan took a break from editing TMD to head over to do a little sweeping with us. Let’s see what he’s thinking about this morning …

In the days immediately following President Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis, the bulk of media coverage focused primarily on a) his health and b) piecing together how many other people in his orbit may have been exposed to the virus. We’ve got a pretty good rundown of both in today’s Morning Dispatch, but this is a campaigns newsletter (plus, Trump could be discharged from Walter Reed Medical Center as early as today if his doctor is to be believed), so let’s take a look at how his illness could play out over the final 29-day stretch.

We obviously don’t have much experience with a presidential candidate testing positive for a potentially deadly virus a month out from an election; these are uncharted waters. But on its face, the diagnosis is bad news for Trump. He’s currently trailing Joe Biden nationally by 8 percentage points. His numbers in potential tipping point states—Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Nevada, Florida—are better, but only slightly. Biden can afford to run out the clock from his basement; any day that Trump is not driving a positive message and making up ground—difficult to do from a hospital room—is a wasted one.

Even if the president is discharged from Walter Reed today, the Centers for Disease Control recommends people “severely ill with COVID-19” stay home and away from others 10 to 20 days after symptoms first appeared. Trump has flouted CDC guidance before—holding indoor campaign rallies with next-to-no distancing and no mask mandates—but he would (rightfully) take a pounding in the press if he went back on the road while still contagious. By the time his quarantine ends, he may well have lost ten days to two weeks of campaign time.

Some have suggested that Trump could receive a “sympathy” bounce in the polls to counteract this politicking hiatus, with voters’ views about the president softening as he battles the invisible enemy. “Were I managing Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden’s campaign,” Institute for Policy Innovation scholar and Trump supporter Merrill Matthews wrote in The Hill, “this would be my biggest fear.”

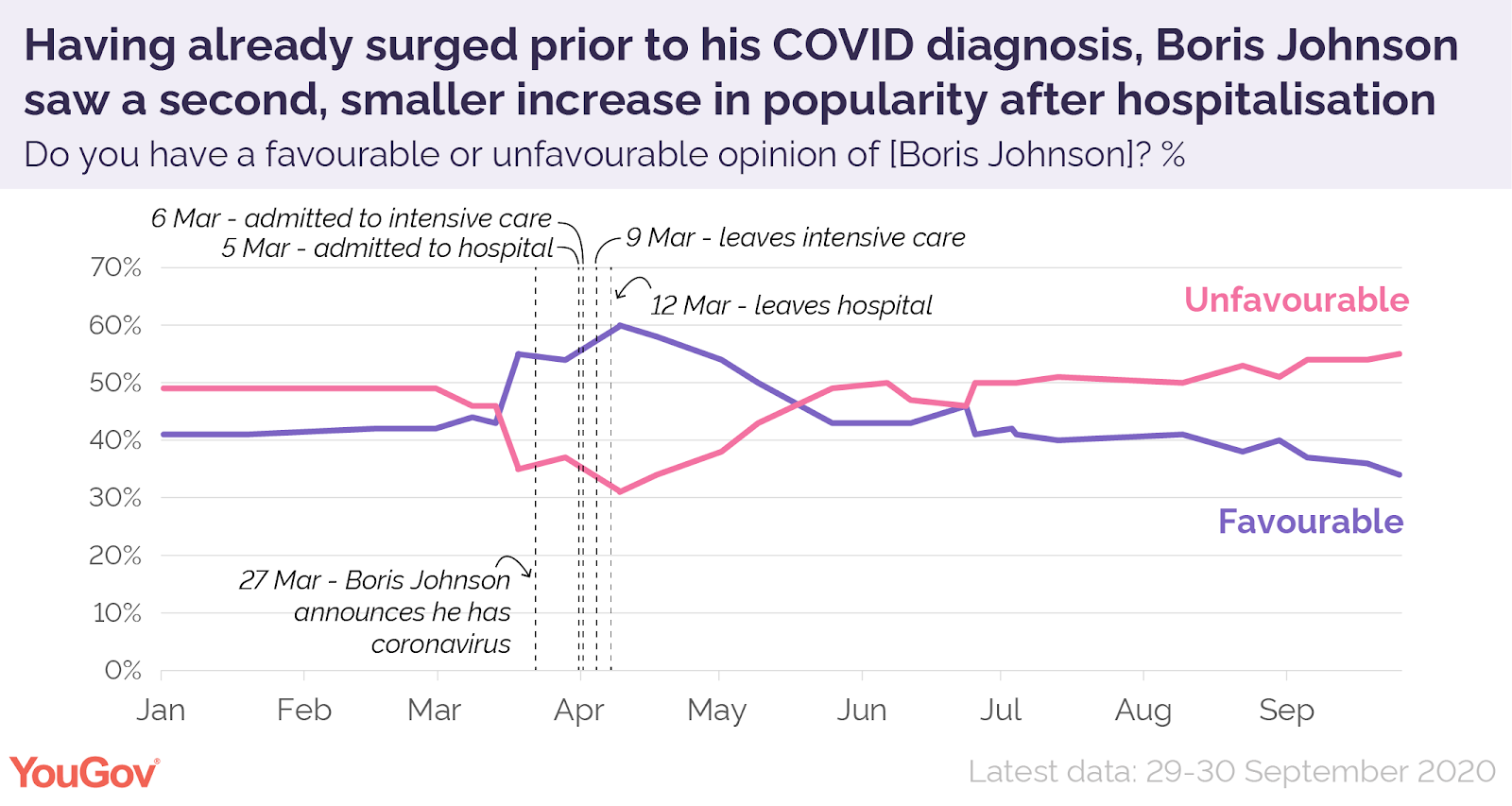

But is the sympathy bounce real? U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s coronavirus infection and subsequent hospitalization last spring provide perhaps the most analogous example. Johnson’s approval rating, per YouGov, jumped up in late March—prior to his own diagnosis—as COVID-19 enveloped Great Britain and the world. It ticked up a bit more, from 54 to 60 percent, when Johnson underwent his own struggle with the virus and was moved to intensive care. It’s impossible, of course, to know for sure whether that bump was entirely attributable to his hospitalization, but we do know this approval was back down to 54 percent in less than a month, and at 43 percent in a month-and-a-half. If he did get a “sympathy bounce,” it was both immediate and short-lived.

Trump only announced his COVID-19 diagnosis about 80 hours ago, but we already have some evidence that any sympathy bounce he might be receiving is not translating to additional electoral support. A Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted entirely after Trump’s positive test found Biden with a 10-point lead nationally, within the margin of error of the 9-point Biden lead from earlier in the week. Two Yahoo News/YouGov surveys—in the field the two days before Trump’s diagnosis and the two days after—unearthed identical results: A steady 8-point national lead for Biden.

Trump’s own rhetoric and actions the past seven months may have blunted his campaign’s ability to capitalize on voter pity. In that same Reuters/Ipsos poll, 65 percent of voters said Trump probably would not have been infected if he “had taken coronavirus more seriously.” A whopping 72 percent of respondents in an ABC News/Ipsos poll believe Donald Trump “has not taken the risk of contracting the coronavirus seriously enough” and did not take “the appropriate precautions when it came to his personal health.”

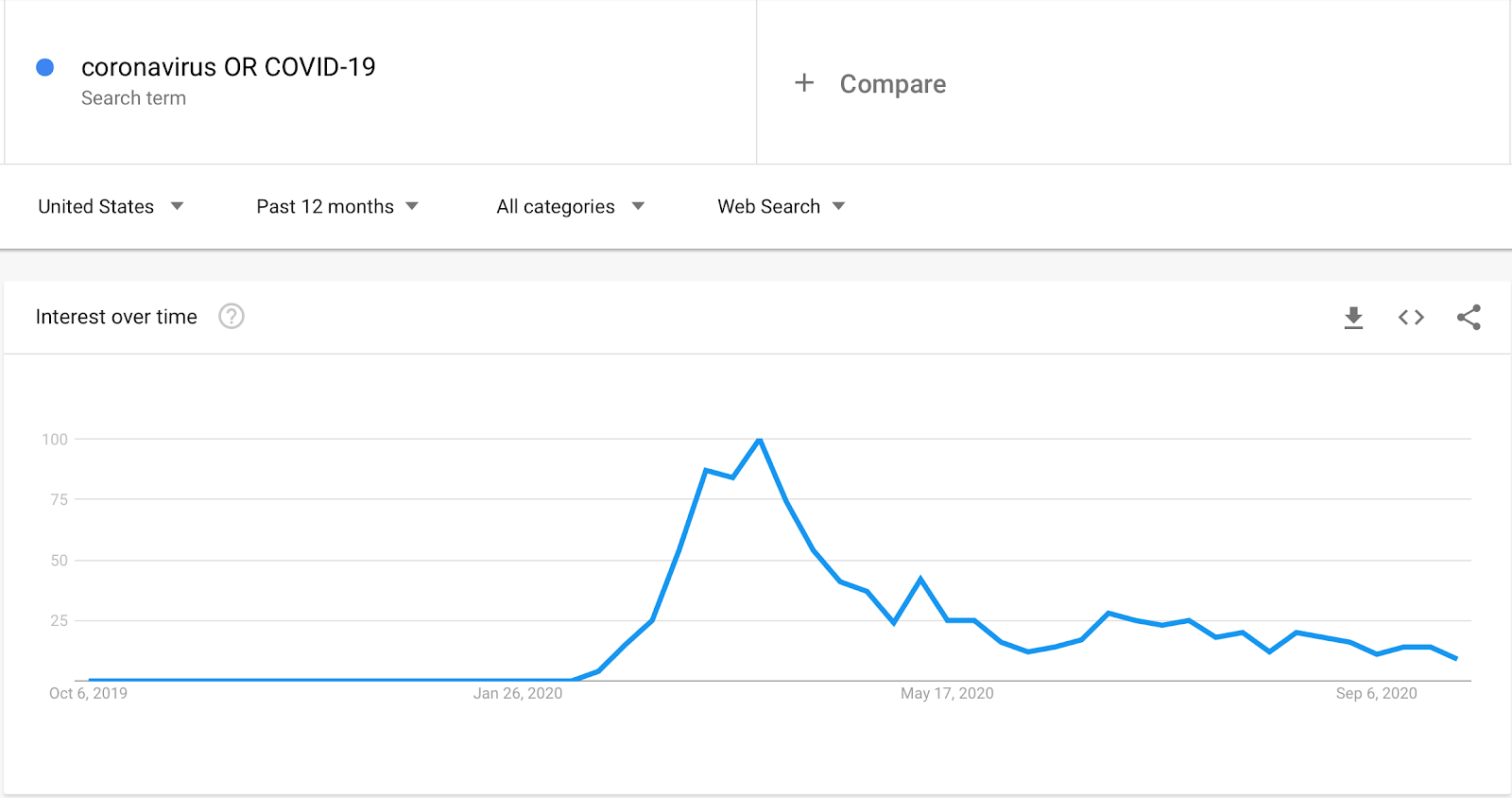

But the most politically damaging aspect of Trump’s case of COVID-19 is not the missed days on the trail or the lack of a sympathy bounce, but rather the shift in conversation it sparked. The coronavirus pandemic had faded from headlines in recent weeks—no longer front page news, but rather a steady drumbeat in the background—despite the fact that an average of nearly 800 additional deaths continue to be attributed to COVID-19 every single day. A Google Trends chart depicts Americans’ relative waning interest in the topic over time.

For Trump, that was a positive. Health care and the coronavirus routinely show up in polls as among the president’s worst issues with voters. Respondents in Sunday’s NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey believe Joe Biden would be better at dealing with the coronavirus 52 percent to 35 percent, and dealing with health care 53 percent to 34 percent. A FiveThirtyEight polling average shows Trump with a -16 net approval on responding to the pandemic. Trump is on much stronger footing when he’s talking about the economy, and slightly stronger footing (though still underwater) when he’s addressing crime and violence or his nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. Any day the main story relates to the former two and not the latter three is not one where Trump will be making up much ground.

The Trump campaign, then, has two options—both longshots—if it hopes to take a bite out of Biden’s lead over the next 29 days: Find ways to move the conversation back to ground friendlier to Trump (difficult to do while Trump’s condition dominates the airwaves), or improve public opinion around Trump’s handling of the coronavirus (difficult to do seven months into the pandemic).

A video of Trump released by the White House may hint at a coming pivot on the latter. “I’ve learned a lot about COVID,” Trump said, appearing to treat the virus with the seriousness it deserves. “I learned it by really going to school. This is the real school, this isn’t the let’s-read-the-book school. And I get it, and I understand it.”

But a short while later, he was riding around in the back of an SUV to wave at a crowd of supporters that had assembled outside of Walter Reed, needlessly putting multiple Secret Service agents at risk of contracting COVID-19.

Do Attack Ads Actually Persuade Undecided Voters?

Let’s go to Audrey with some analysis of the ad wars this week …

Joe Biden’s campaign decided on Friday to pull negative ads while President Trump is hospitalized at Walter Reed Medical Center, although it may take several days before the ads are officially taken off the air.

The Trump campaign did not reciprocate the move. “Joe Biden used his speech in Michigan today to attack the president repeatedly on Social Security, the economy, and job creation,” Trump campaign spokesman Tim Murtaugh told CNN Friday. “Now Biden wants credit for being magnanimous.”

Could the strategy hurt Biden? Some Democrats have suggested it’s an unnecessarily charitable move. “Why would Biden delay or suspend his campaign when we know Trump would’ve had ads up by noon today ridiculing Biden for testing positive?” tweeted Rep. Ilhan Omar on Friday. “Get it together.”

Yet there’s some reason to suspect that overreliance on anti-Trump ads could be counterproductive for Biden’s campaign anyway. “The scary, doom-and-gloom, negative campaign spots that you typically see in an election year not only aren’t working with people that we want, they’re causing backlash among the people we need,” Democratic strategist Jess McIntosh recently told Vanity Fair. “Trump is so saturated. You can make the case that you want to make without even saying his name.”

That assumes that there remains a trove of undecided voters out there who are theoretically open to persuasion from either the Trump or the Biden camp, and who theoretically could be repulsed by one campaign going too negative. In this particular election, that may not be the case.

“There are fewer and fewer persuadable voters,” David Kochel, a campaign consultant who has been in the trenches of GOP politics for three decades, told The Dispatch. “It didn’t start with President Trump, but his style of politics certainly puts it on steroids.”

On the one hand, even when there are fewer swing voters than ever out there, simply ignoring them still carries an electoral cost, particularly in battleground states. “I’m in Iowa right now, and we’ve got $150 million on the air between the two Senate candidates,” Kochel said. “And that’s aimed at 1.8 million voters, 95 percent of whom have already made up their minds. So you’re talking about a lot of money being aimed at a pretty small group of available persuadable voters, and I think for a lot of people it might seem like overkill, but the money is there to spend.”

But on the other, it’s easy to see why the presidential campaigns are primarily focused on turning out their bases this year. “Presidential elections for the last 20 years now have been base strategy elections, pretty much on both sides,” said GOP strategist Rob Stutzman, who served as deputy chief of staff for communications to Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. “[2016] was obviously the ultimate base election. Hillary’s didn’t like her, they didn’t vote, Trump wins. So what we see this year is the same thing.”

Photograph by Alex Edelman / Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.