Campaign Quick Hits

Follow Tuesday: If you read this newsletter, odds are you like getting into the weeds of campaigning. So Andrew, Chris, and I thought that for the next few weeks we would highlight some other folks y’all might be interested be reading and following this cycle in their areas of expertise. This week, we’re focused on redistricting, and when it comes to how maps are getting redrawn out there, our favorite people to turn to are:

Dave Wasserman (@redistrict)

Amy Walter (@AmyEWalter)

Patrick Ruffini (@PatrickRuffini)

Geoff Skelley (@geoffreyvs)

Kyle Kondik (@kkondik)

Nathan Gonzales (@nathanlgonzales)

J. Miles Coleman (@JMilesColeman)

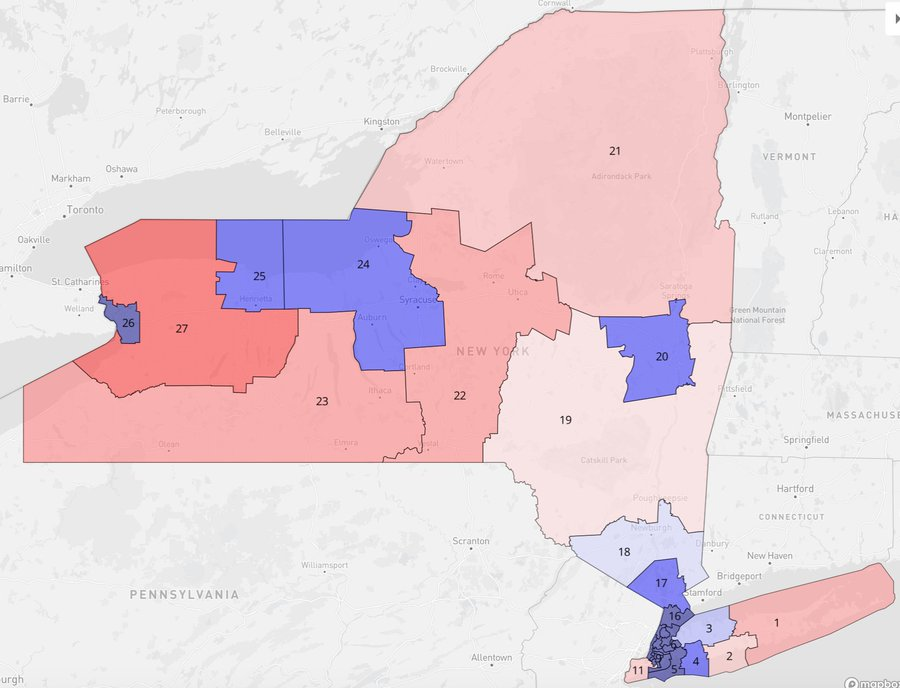

What Gerrymandering Looks Like: Speaking of which, Dave Wasserman, who edits the Cook Political Report, recently tweeted that “strategists I’ve spoken w/ tell me strong census numbers in NYC could help Dems purge as many as *five* of the eight GOP seats in the state.” This is another great reminder that when Biden-won states like New York and Illinois lose seats in the census, it actually translates into losses for Republicans—not Democrats. Yes, the blue state itself gets less representation in Congress, but the also-blue state legislature that draws the districts can use the opportunity to ensure that reliably Republican voters are smushed into as few districts as possible. Compare New York’s current map:

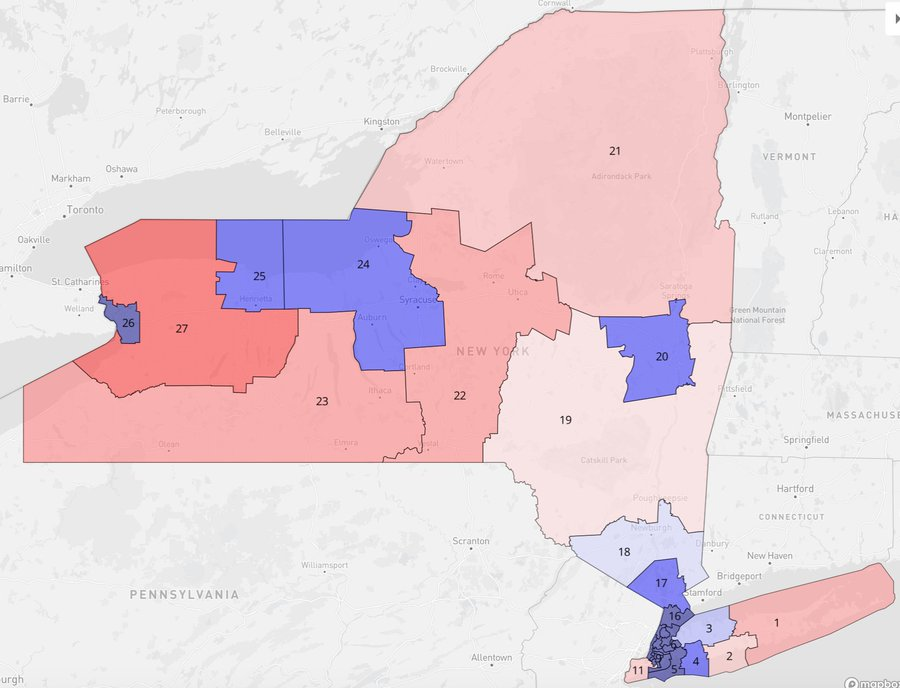

… with this hypothetical map drawn by Wasserman, using the latest census data:

Meet The Next Generation: Gen Z may account for less than 10 percent of the electorate these days, but the kids are our future, after all, and Alex Samuels at FiveThirtyEight has done a deep dive into how this new political bloc is shaping up. Once again, lazy operatives have used this upcoming generation as another card in the ‘Future Permanent Democratic Majority’ house. But despite breaking for Biden by 20 points in 2020, “some research suggests that Gen Zers are no more likely to identify as members of the Democratic Party than registered voters in the overall electorate, and a plurality is unwilling to identify with either political party.” And, not surprisingly, “there’s already some evidence that today’s younger liberals might get more conservative as they get older, and roughly one-third of Gen-Z voters who don’t identify as Republican said that they would consider voting for a moderate Republican candidate, according to a June 2020 survey by the Niskanen Center.” Republicans are not on the verge of winning over these youngest voters anytime soon, but Gen-Z may still just be in the hookup phase with the Democrats.

Quote of the Week: “Between 99 and 100 percent. I think he is definitely running in 2024.” —Trump campaign advisor Jason Miller on the chances of his boss running for president again.

The politics of abortion is back front and center. As Jeff Goldblum once said, “the pro-life movement was so preoccupied with whether they could get around Roe and Casey in the courts they didn’t stop to think about whether they should pass a bounty hunting abortion law.” Chris has thoughts:

GOP’s Litigious Streak Will Cost Seats

I’ll let the lawyers hash out the policy consequences of the new Republican enthusiasm for legal activism, but as a political matter, efforts to turn the courts into vehicles for right-wing social engineering will be no more popular with voters than the left-wing variety was.

It is perhaps an understandable byproduct of the Trump administration’s success in remaking America’s federal courts that Republicans would be so litigious lately. Believing they would now get a fair shake—maybe even quietly agreeing with Democrats who say the federal courts are now rigged for the red team—Republicans have gone from being the party of tort reform to becoming the party of legislation by litigation.

For instance, a great deal of what Republicans intend to do about what most in their party believe is a bias against them on news and social platforms involves making it easier to sue—more libel lawsuits against news outlets and a whole new cause of action to allow Americans to sue over being banned or restricted online. Republican state attorneys general have embraced the former role of their Democratic counterparts of playing Robin Hood for consumers on mass litigation and are developing some creative reads on antitrust suits.

While this is all also a reflection of the anti-business, anti-market bent in the increasingly populistic GOP, this new Erin Brockovich-style approach to public policy by litigation relies on a degree of confidence that Republican-backed causes will get a favorable hearing in court. With 226 Trump appointees on the bench—more than a quarter of all federal judges—Republicans have sound basis for their confidence. And with only one fewer appellate court confirmation than Barack Obama got in two terms, Donald Trump can certainly say that he and Mitch McConnell made the most of four short years. While they did not do as well as fellow one-termer Jimmy Carter (261 appointments), they certainly outperformed George H.W. Bush (187 appointments).

But the headwaters of the Republican love for legal activism—the same spring that fed the deep pool of Trump nominations—is in the pro-life movement. When the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision striking down state-level bans on elective abortions before the six-month mark was decided, social conservatives reasonably concluded that the federal bench was hostile toward their interests. For nearly 30 years under chief justices Earl Warren and Warren Berger, the Supreme Court embraced progressive social activism, placing itself on a plane above lowly lawmakers on such issues. Given the refusal of most lawmakers to take on challenging issues, maybe they’re the ones to blame. But whatever the causes, the courts came to be seen as the left’s most powerful bastion in the culture wars.

The Republican Party of the era joined defenders of economic liberty with defenders of traditional values—what has been called the “leave us alone” coalition. Their approach to the courts reflected that concept and was rooted in the knowledge that the legal system was hostile to conservatism. The idea was to stay out of court, but to be prepared to weather the legal activists’ storm surges when they did arise. As for fixing the problem in the long term, some on the right focused on changing the judiciary, while others focused on getting craftier in using the courts to achieve right-wing objectives. While the Federalist Society was building the more conservative, restrained judiciary of the future, religious law schools across the country started turning out lawyers trained to work around Roe v. Wade to restrict abortion. One part of the GOP legal team went to fight against legal activism. The other went to get good at it.

Those two projects reached a culmination last week when the Supreme Court majority, including three justices picked by the Federalist Society, let stand a Texas law that reflects the new GOP enthusiasm for civil litigation. While Texas’s new abortion law is described by its many opponents as a ban on abortions after six weeks, it’s really using the courts to crowdsource legal hassles for abortion providers. While other states have seen similar “heartbeat” bills either languish or be overturned, the attorneys in the Texas legislature figured out that if the state is relying on “citizen suits” to get around Roe, the court couldn’t say that Texas was restricting elective abortions in advance, only that it had created a new pathway for lawsuits. The pro-life majority on the court said as much in its decision letting the law stand. Texas Republicans found a loophole.

Now, abortion pales in comparison to economic and public health and safety issues when it comes to moving persuadable voters. Like foreign policy, the abortion fight strongly motivates activists but generally doesn’t move the folks in the middle—unless something serious happens. While the issue set for midterms continues to set Republicans up well to win back the House and possibly the Senate, this kind of legal activism on a hot-button issue cuts the other way. If Democrats succeed in making the Texas law a source of panic and other Republican states follow Texas’s tortuous path, it will cost the GOP seats next year.

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem is itching to throw her hat in the 2024 presidential ring, but navigating the politics of the “pre-candidate” phase can be a doozy—and all the more so for a governor in a one-party state. Over at the site today, Andrew has a piece breaking down a fight between Noem and her state’s Republican legislators over legislation to ban private vaccine mandates—which is worth a look here, given the backdrop of how Noem is trying to define her presidential-hopeful brand.

2024 Watch: Kristi Noem and The Vaccine Mandate Ban

The debate over vaccine mandates has been raging for months, but it has heated up in Gov. Kristi Noem’s backyard in recent months. South Dakota’s largest employer is Sanford Health, a hospital and health care system that employs nearly 10,000 people in the eastern half of the state. On July 22, Sanford, which operates in both Dakotas and Minnesota, announced it would begin requiring all its employees to get vaccinated for COVID by November 1.

Within weeks, two Republican members of the state House, Reps. Jon Hansen and Scott Odenbach, had introduced legislation punching back. The COVID-19 Vaccine Freedom of Conscience Act would give South Dakotans “the right to be exempt from any COVID-19 vaccination mandate, requirement, obligation, or demand on the basis that receiving a COVID-19 vaccination violates his or her conscience.”

…

The only problem: Noem doesn’t support the legislation.

It’s not that she’s the sort of Republican, a la Ohio’s Mike DeWine, who’s tried to keep her state COVID policies simpatico with the recommendations of the CDC throughout the pandemic—far from it. South Dakota never issued a stay-at-home order and was the only state that never required businesses to close last year. Although South Dakota weathered a heavy COVID surge relative to its neighbors, Noem’s supporters say her approach is responsible for helping the state rank among the best in the country in current economic performance relative to pre-pandemic levels.

Now, however, the laissez-faire approach that made Noem a conservative folk hero in last year’s fights has gotten her crosswise with her fellow Republicans on the issue of vaccine mandate bans.

“Frankly, I don’t think businesses should be mandating that their employees should be vaccinated,” she said in a video posted to Twitter last week. “And if they do mandate vaccines to their employees, they should be making religious and other exemptions available to them. But I don’t have the authority as governor to tell them what to do. And since the start of this pandemic, I have remained focused on what my authorities are and what they are not. Now South Dakota is in a strong position because I didn’t overstep my authority. I didn’t trample on the rights of my people, and I’m not going to start now.”

This response quickly ran afoul of some national conservative pundits. “I am done, and have been done for a long time, with these Republicans who are too afraid to use their power,” the Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh said on his podcast. “No use for these Republicans who have made themselves useless.”

But this flippant response obscures what is in truth an interesting and pressing divide in philosophy between two types of “small government” conservative. The basic issue dividing Noem from other Republicans in her state isn’t a silly matter of which leader has the will to seize the reins of power to bring about good policy. It’s a question of what it means for a state to preserve freedom among its citizens. Is it, as Republicans have long supposed, primarily the role of government to get out of the way and let its citizens form private relations as they see fit? When is it the role of the state to insert itself into private relationships, like those between employers and employees, to ensure the powerful are not limiting the liberty of the powerless?

Read the rest of Andrew’s piece here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.