Welcome to our year-end edition of The Collision! We’re going to close out 2023 with a quiet, thoughtful reflection on all the fun moments we had this year documenting the collision of law and—just kidding. Given the times in which we live, of course we’re turning things up to 11 just as everyone is trying to wind down the year with some holiday cheer.

We’ll dive deep on the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to remove Donald Trump from the state’s primary ballot on 14th Amendment grounds, as well as what we can expect from the U.S. Supreme Court in response. Meanwhile, Trump’s legal team has responded to the government’s petition to have the Supreme Court review the presidential immunity question. And we’ll also examine some upcoming developments with Hunter Biden and his refusal to comply with congressional subpoenas.

One programming note: We’ll be taking next week off for the Christmas holiday. To all our readers who celebrate, Merry Christmas. Thanks for reading, and we’ll be back in your inboxes in 2024.

The Docket

- Our actual newsletter this week is too full, so let’s consider the docket cleared for now.

The Problems With the Colorado Election Decision

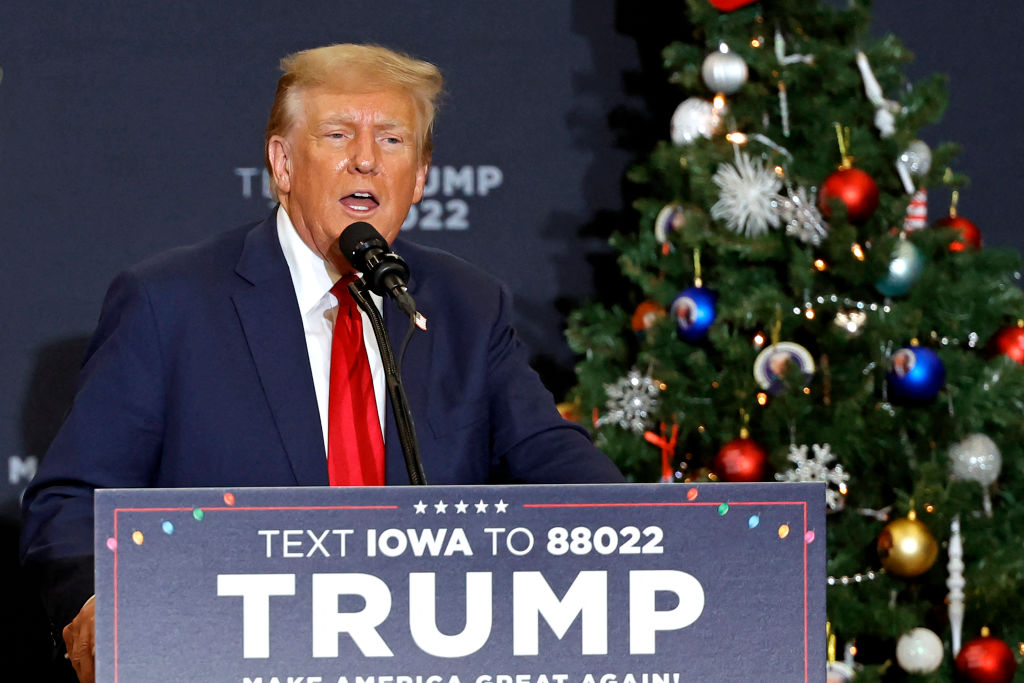

In a 4-3 decision released on Tuesday, the Colorado Supreme Court held that Donald Trump could not appear on the Republican primary ballot in the state because he was disqualified to serve as president by Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. The seven justices comprised the fourth court to consider this question in the context of January 6, but the only one that has decided to keep a candidate from appearing on the ballot. Notably, the court stayed its decision pending review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

First, let’s start with the Colorado Supreme Court. Each justice is appointed by the state’s governor, which means all seven justices are Democratic appointees—making the narrow split all the more interesting. Second, let’s remind ourselves what the text of this part of the 14th Amendment actually says (with the parts we’re debating these days in bold):

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The purpose of this 1868 amendment wasn’t to prevent anyone who had fought for the Confederacy from holding office, but specifically to target those who had broken their word, i.e. a member of Congress who had sworn to defend the U.S. Constitution but then turned around and fought to dismantle it. That person can’t come back and take the same oath again with any credibility.

In this case, four Colorado justices held that Trump was ineligible from becoming president again because he neglected his presidential oath to support the Constitution when he gave a speech inciting an insurrection on January 6.

The argument supporting this conclusion should be pretty obvious if you accept that the violence at the Capitol on January 6 was an insurrection. But there are compelling arguments on the other side—some of which the dissenters point out and some of which Sarah will get into below.

For starters, the text of the amendment never says anything about the president. In fact, it lists a lot of other offices specifically—including electors of the president or vice president—but not the president or vice president themselves. An earlier draft of this section of the amendment did specifically list the president, but that reference was taken out, which might lead one to conclude that the amendment’s authors did not intend to include presidents for whatever reason. (There’s no surviving record of why it was removed.) But a senator brought up this very point during the debate over the 14th Amendment in 1866, and another senator said the catchall “office under the United States” included the presidency.

But a side conversation between two senators more than 150 years ago doesn’t necessarily have the binding force of law. The phrase “officer of the United States” appears several other times in the Constitution, and the instance with the biggest implication for the Colorado decision comes in Article II, stating the president “shall Commission all the Officers of the United States” (emphasis added). One interpretation would be that the president doesn’t commission himself, therefore he must not be an officer of the United States.

The next problem with applying this section of the 14th Amendment is what to do about the insurrection or rebellion stuff. The Colorado decision held that Donald Trump “engaged” in an “insurrection” during his speech that day. Trump, obviously, hasn’t been convicted of—or even charged with—participating in an insurrection under the legal definition of the word. So the Colorado Supreme Court had to find on its own both that January 6 was an insurrection under the law and that Trump engaged in it because his speech was inciting violence and therefore not protected by the First Amendment. To qualify as incitement under the Supreme Court’s Brandenburg test, a person’s words must a) encourage the use of violence, b) be intended to result in the use of violence, and c) likely result in violence.

All of this generates a number of questions, but one stands above the rest: Who gets to decide? The language of Section 3 doesn’t offer definitions of these terms (what is an insurrection versus a riot?) or explain what level of evidence is required. (Proof beyond a reasonable doubt? More likely than not? Clear and convincing evidence?) Nor does it say who should decide these questions. On the one hand, not every constitutional amendment requires congress to pass enabling legislation, including other parts of the 14th amendment.

But the 14th Amendment was meant to curtail states’ power. It was added to the Constitution in response to a civil war brought about by states and precipitated by a concept of “states rights,” after all. So the idea that each state court gets to decide its own standards for whether a federal candidate can be on the ballot would seem a little odd. But Section 5 of the 14th Amendment offers some clues to this question of who decides: “Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” Indeed Congress did so with the 1870 Enforcement Act, which created various ways to enforce the 14th Amendment. And there is, as the dissent in Colorado notes, “a federal statute that specifically criminalizes insurrection and requires that anyone convicted of engaging in such conduct be fined or imprisoned and be disqualified from holding public office.”

According to this argument, Section 5 makes clear that Congress is responsible for deciding these questions, Trump hasn’t been charged under the law Congress created, and the courts don’t get to do an end run around that law when it comes to telling the American people they can’t vote for their candidate of choice.

Sarah’s View

So how will this whole thing turn out? The U.S. Supreme Court will weigh in one way or another in the next few days. My best guess is that the justices will first issue an administrative stay barring this ruling from going into effect, which gives the Supreme Court more time to consider the question. The justices could also simply announce they are taking the case, which will have the same effect.

Most legal scholars agree the Supreme Court is likely to reverse the Colorado decision, but we might disagree on the hows and whys. I think this will be a per curiam opinion, meaning that it will be unsigned by any justice and that there will be no noted dissents. That doesn’t mean it was unanimous, but it will mean that we also won’t know if it was 6-3, 7-2, etc. The other option (the best case scenario, in my opinion) is that the court goes out of its way to ensure this is a 9-0 decision, finding that this section is not self-executing and it is not up to courts to define all of these terms and what evidence is required to prove them without congressional input.

Regardless, this is the biggest test of the court’s credibility since Bush v. Gore but at a time when Americans trust in our institutions is far lower and the security of our system of government feels far more tenuous. Godspeed to the nine.

Donald Trump Hits Back on Presidential Immunity

There’s an underlying theme to Donald Trump’s response to special counsel Jack Smith’s petition for the Supreme Court to take up the question of presidential immunity: Slow. It. Down.

Near the top of the 44-page document that was filed Wednesday, Trump’s lawyers argue that Smith is attempting to “bypass … ordinary procedures” by going straight to the Supreme Court while the D.C. Circuit Court has already expedited its review. Why force the highest court in the land to answer the question when the process is already at work in a lower court—and especially, the Trump team’s brief notes multiple times, when judgments at the district court level have already been in the special counsel’s favor?

The Trump team has an answer: It’s Smith’s “manifest partisan interest in ensuring that President Trump will be subjected to a months-long criminal trial at the height of a presidential campaign where he is the leading candidate and the only serious opponent of the current Administration.”

But there’s another, nonpartisan reason Smith may want to address questions like immunity quickly and get to a trial: His window for prosecuting Trump on the election-interference charges could very well close if Trump is elected president. Smith is a career prosecutor and has not said this outright, only stating in his brief that this is an “extraordinary request” for an “extraordinary case.” And, of course, Trump himself has his own partisan interest in making sure prosecutors face every procedural roadblock in order to delay the trial until, well, after his successful election.

Regardless, the Supreme Court will have to decide in the next few days whether to preempt the circuit court’s current plans for review, including oral argument set for January 9. And more broadly, whether the “winning side” ever gets to appeal is at the mercy of the losing side’s timetable.

We know where the Trump team comes out. Quoting a decision from an obscure mail fraud case, the Trump brief notes, “‘Haste makes waste’ is an old adage. It has survived because it is right so often.” In other words: Don’t let the government speed things along unnecessarily.

House GOP Looks Poised to Press Hunter Biden

When the House of Representatives gets back to work in early January, expect the Oversight and Judiciary committees to follow through quickly on their respective chairmen’s threats to hold Hunter Biden in contempt. That’s according to two sources on Capitol Hill with knowledge of those plans who spoke to The Collision. On their estimated timeline, we could be looking at the son of the president being held in contempt of Congress in less than a month.

A quick recap of how we got here: In November, the two committees leading the inquiry into impeaching President Joe Biden subpoenaed Hunter Biden, calling on him to sit for a private deposition and answer questions about his foreign business dealings and financial records. But Biden insisted on only testifying in a public hearing, a request House Republicans did not acquiesce to. So on December 13, Biden failed to show up, instead holding a press conference outside the U.S. Capitol denouncing congressional Republicans. Soon after, GOP Reps. James Comer and Jim Jordan, who chair Oversight and Judiciary, respectively, said they would pursue contempt procedures.

So what happens next? According to our sources, because both committees issued separate subpoenas of Biden, each will pursue its own report of contempt—likely, but not guaranteed, criminal in nature. A member of each committee will introduce a resolution, which will have to go through the standard practice of being marked up, with amendments to the language in the resolution considered. Then, the committees will vote on their resolutions. There seems to be little expectation that the Republican majority on each committee won’t be able to get its resolution passed. But per House rules, this whole committee process will take a minimum of three working days.

If the resolutions pass through their respective committees, House leadership will decide when to bring the resolutions for a vote on the floor. Again, don’t expect any surprises since House Speaker Mike Johnson has expressed and demonstrated support for the impeachment inquiry so far, which is probing whether Joe Biden improperly involved himself in Hunter Biden’s international business activities. But how will a vote on the floor go? This is where things could get complicated.

After former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy resigns on December 31, Republicans will have just a two-seat majority, barely able to afford any defections if Democrats are united in opposition. Things will get even tighter in the event of any unexpected GOP absences. While it’s almost certain no House Democrats will cross the aisle and vote to hold the Democratic president’s son in contempt, will any Republicans split from their conference? Perhaps. Several GOP members hail from districts Joe Biden won in 2020, and while they may have voted to move the impeachment inquiry forward, it’s possible their own political considerations back home could make a Hunter contempt vote a difficult one. But even the most moderate Republicans in the House may be institution-minded enough to believe that defying a congressional subpoena, no matter the reason, should not go unchecked.

Assuming Republicans can pass their contempt resolutions, we will finally reach the moment when the criminal justice system takes over. The Justice Department will receive the referrals and then … consider them. While the DOJ did not answer questions from The Dispatch about what contempt referrals may be coming, it’s of course up to it, not Congress, to decide whether to prosecute.

We know one thing: If the Justice Department takes its time—or declines—to prosecute Hunter Biden on contempt, Republicans in Congress will cry foul.

One More Thing

Don’t forget that more than two years ago Steve Bannon, the former White House aide and MAGA media impresario, defied a congressional subpoena from the House select committee investigating the riot at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Not only did the Justice Department prosecute Bannon, but the case went to trial and he was convicted in July 2022.

In October of that year, he was sentenced to four months in prison, but Bannon soon appealed both his conviction and sentence. A three-judge panel on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals finally heard his attorney’s case for appeal last month, all while Bannon has remained free and continues to host his daily pro-Trump broadcast. While the judges sounded skeptical of Bannon’s arguments, we’re still awaiting their decision.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.