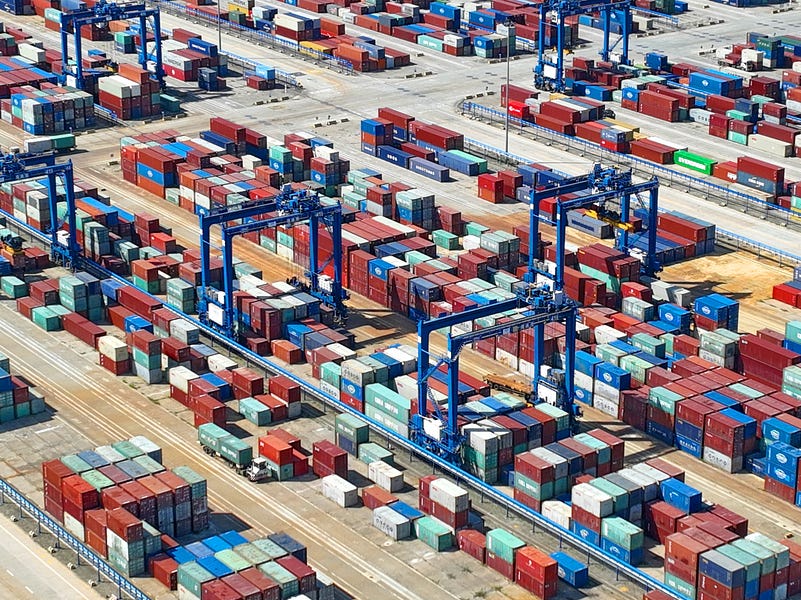

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act went into force just three months ago, and it has already had an effect. But Xinjiang’s role in the global economy is so immense—and the Chinese government’s transfers of ethnic minorities to other parts of China to work are so sweeping—that the American government still has a long way to go in stopping products made with forced labor from coming into the United States.

From October 1 of last year through mid-September of this year, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) targeted more than 3,600 shipments worth nearly $800 million from around the world for potential ties to forced labor, according to Eric Choy, acting executive director of CBP’s trade remedy law enforcement directorate. He told The Dispatch in an interview Monday that of those, around 1,500 were targeted under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, adding up to about $420 million.

“Targeting” in this case means identifying a shipment for further inspection, a CBP spokeswoman clarified. Choy’s numbers reflect those reviews, a subset of which ended in shipments being detained at ports of entry. In some instances, companies have decided to re-export targeted shipments to other countries rather than go through the CBP process under the new forced labor law. Those re-exports will not show up in the final fiscal year 2022 statistics on detentions, but they are included in the larger targeting number Choy shared.

Government officials and businesses will be watching closely in the coming weeks for new numbers from CBP on detentions, including the months since the new law went into effect. CBP detained a total of 1,469 shipments for forced labor concerns last fiscal year—before the Uyghur forced labor law passed—adding up to $486 million.

Experts believe those numbers will be significantly higher this year, although full implementation of the law is still a work in progress. In the interim, Choy’s estimates offer the clearest glimpse yet of how effective the law has been in its early stages.

“This is definitely a ball that is rolling and continues to roll fast,” said Choy.

The law, passed in December, presumes all items made in part or in whole in Xinjiang—a northwest region of China where the Chinese government is committing genocide against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz ethnic minorities—are tainted with forced labor. Members of Congress introduced the legislation to shore up America’s existing ban on forced labor imports and to encourage companies to leave the region.

None of the detained products have been released.

Choy said none of the shipments that have been detained under the Uyghur forced labor law thus far have been released into the U.S. market. While companies can apply for exceptions, CBP hasn’t yet received any of those requests. Firms seem to understand they face long odds.

Under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, exceptions will come only after companies provide “clear and convincing” evidence that forced labor is not present in their supply chains. This evidence is almost impossible to collect in Xinjiang, as independent audits cannot be accurately conducted given the scope of human rights abuses and likelihood that workers would be intimidated against speaking candidly by officials.

Rather than request exceptions to the law, Choy confirmed companies have been trying to make the case that CBP has detained goods not actually from Xinjiang nor touched by implicated entities. Inside U.S. Trade first reported this dynamic last month. CBP theoretically could slip up in some cases—mixing up companies with the same name, for instance—but the fact that every business contesting detained products has made that argument raises questions about what kind of evidence businesses are submitting.

“A lot of times they just don’t understand the depth that we look at within supply chains,” Choy explained. “Under the UFLPA, that is just a much stronger case that needs to be made."

Ana Hinojosa, who previously served as executive director of Choy’s team and departed the agency late last year, said she believes some businesses are pursuing the second option because those decisions would not have to be reported to Congress like exceptions would, and they appear easier to obtain.

“The reality is both of them are going to be very difficult to overcome because CBP isn’t stopping everything,” said Hinojosa. “They’re stopping shipments of goods that they have good information that they’re connected to Xinjiang.”

Companies want more transparency.

John Foote, an attorney who helps businesses comply with the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (and who has a newsletter dedicated to it), told The Dispatch that when CBP detains a shipment, the agency simply issues a notice citing the bill.

“You are left to guess everything else,” he said. Foote argued more information about which services CBP is using to identify forced labor ties would help companies know where to start in checking on their supply chains when they have shipments detained.

“Because customs does not want to tell the world if it has access to information other than import data or what information it has access to—it regards that as law enforcement activity and therefore regards it as a closely guarded secret—you don’t even know what you’re shooting against,” Foote added.

Others have prodded the government to provide new supply chain mapping tools to companies.

Choy said Monday he is aware of calls for CBP to “provide greater transparency of who and who not to do business with,” but it’s not necessarily “something the government could efficiently do.”

Major gaps remain, as Xinjiang still permeates supply chains.

American consumers can’t be certain yet that their money isn’t propping up slave labor. Inputs from Xinjiang can be found in supply chains around the globe, and recent reporting by human rights organizations and journalists has identified items hiding in plain sight that should have been stopped from entering American stores.

The Uyghur Human Rights Project published an investigation last month that found red dates connected to the region or the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a sanctioned paramilitary organization, in seven grocery stores in the D.C. area. They also identified e-commerce sites that were offering Xinjiang dates for shipping to the United States.

Perhaps some screening officials didn’t connect the name “Bingtuan” on the packaging with the XPCC. The companies selling them may have also submitted false paperwork about the products. Hinojosa, the former CBP official, believes the agency will be “better able to target” the dates going forward. Yet with that information now public, she said she would not be surprised if shipments begin to arrive with new labels less easily tied to Xinjiang and the XPCC.

Choy said reports like those about the red dates give his team insight and information to chase down, a “cat and mouse game that we have to play.”

It’s not clear how many products across all industries have come into the United States from Xinjiang since the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act went into effect. The South China Morning Post reported Monday that Chinese data shows exports from Xinjiang to America in August were at a surprising 10-month high of $56.8 million.

“I think there’s a little bit of an information campaign ongoing from the PRC to potentially marginalize the UFLPA or even the EU’s new legislative efforts that are ongoing,” Choy said, referring to recent European Union debate about an anti-forced labor trade law. “But certainly our data just doesn’t mirror up with what that’s showing.”

Officials look to the next stage.

Some industries have not yet been affected by the forced labor law, but everyone is watching the next phase of the bill’s implementation: An expansion of the government’s entity list targeting companies and organizations involved in forced labor transfers.

All products touched by the Xinjiang region are banned under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act—as are all products touched by businesses or entities that have accepted Uyghur workers or other ethnic minorities through the Chinese government’s forced labor transfer schemes.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute found that more than 80,000 Uyghurs were transferred out of Xinjiang to other parts of China to work between 2017 and 2019. The think tank identified more than two dozen factories across the country that were using transferred Uyghur labor, touching the supply chains of 82 global brands. And Xinjiang’s labor transfers have likely continued at a volume comparable to previous years, according to a recent paper by German researcher Adrian Zenz, who also found that the Chinese authorities have made such moves more difficult to track.

Frederic Rocafort, an attorney at Harris Bricken, said companies he works with are starting to more fully grasp the potential for exposure throughout China. But he said filling out the entity list will be a tall order for the government: “I think they themselves have a certain trepidation about what that could potentially mean.”

Choy described potential additions to the entity list as a “target-rich environment.”

Congress has focused on this aspect of enforcement. In July, a group of Democratic lawmakers wrote a letter to the administration asking why several solar companies that had been implicated in forced labor transfers were not included on the list.

Those companies are still not on the entity list. Choy said Monday the letter is being reviewed and responses are being drafted.

In its communications with Congress, CBP has emphasized a need to hire more personnel to fully enforce the law.

“We’re talking about new CBP officers, import specialists, lawyers,” Choy said. “There’s a broad kind of general growth across the agency, because really when it comes to the forced labor enforcement, this has been an all-hands-on-deck kind of enforcement requirement for us.”

On the Floor

Both chambers will work to pass a short-term government funding package this week. Proposed legislation released Tuesday morning would give negotiators through mid-December to agree on a larger spending bill. It includes more than $12 billion in aid to Ukraine and a controversial permitting package sponsored by Sen. Joe Manchin. The details may change throughout the week.

The House may also consider a bill barring lawmakers from trading individual stocks.

Key Hearings

The Senate Judiciary Committee will meet Wednesday morning for a hearing on accountability for war crimes, including in Ukraine. Information and livestream here.

Administration officials will appear before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Wednesday morning to testify about the U.S. response to Russia’s war in Ukraine and how America could pressure Russia more. Information and livestream here.

The January 6 investigative committee is slated to hold a public hearing Wednesday afternoon. Information and livestream here.

The House Veterans’ Affairs Committee will meet Thursday for a hearing on veteran suicide prevention. Information and livestream here.

The Senate banking panel will examine outbound investment in a hearing Thursday morning. Senators are likely to focus on China and national security concerns. Information and livestream here.

A House Science, Space, and Technology subcommittee will examine managing the risks of artificial intelligence during a hearing Thursday morning. Information and livestream here.

The House Natural Resources Committee will meet Friday morning for a hearing on Puerto Rico’s disaster recovery and power grid. Information and livestream here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.