Good morning. The House is out this week, while senators continue to consider some of President Joe Biden’s Cabinet nominees.

The Senate approved former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen as Biden’s treasury secretary last night, with an 84-15 vote. Yellen is the first woman to lead the Treasury Department.

The Trial Kicks Off

The House impeachment managers delivered the article of impeachment accusing former President Donald Trump of inciting insurrection to the Senate last night, triggering the formal start of the trial. Still, arguments won’t begin until the week of February 8, as party leaders have agreed to delay proceedings to allow both sides more time to prepare.

It has become increasingly evident over the past several days that pulling together the requisite 17 Republican votes to convict Trump in the Senate will prove a tall order, if not impossible. It’s likely that several GOP senators will ultimately choose to convict Trump—people like Sens. Mitt Romney, Lisa Murkowski, Pat Toomey, and Ben Sasse—but the path to 17 votes within the Republican conference appears very narrow.

Some of my former CNN Hill team colleagues spoke with more than a dozen Republican senators last week, coming away with the impression that most Republicans will vote to acquit Trump unless even more damning evidence emerges “or the political dynamics within their party dramatically change.”

“The chances of getting a conviction are virtually nil,” Mississippi Republican Sen. Roger Wicker predicted.

There are a couple of forces at play here. First, the echo chamber: Every day that passes between January 6 and the beginning of trial arguments is another day Republican senators will be absorbing talking points against impeachment from conservative media sources and their constituents.

As my friend Matt Tait observed, “What folks don’t seem to get is that the Senate trial already started. It’s just playing out on Fox News[,] not on the Senate floor.”

Trump himself recognizes the delay works in his favor. The New York Times’ Maggie Haberman reported Sunday that Trump has started to believe there are fewer votes to convict today than there would have been if the trial and a vote had been held almost immediately after the attack on the Capitol.

The initial sense of urgency to hold Trump accountable and senators’ clarity about what they experienced that day both diminish as time passes and partisans spin the facts to try to cast Trump and his allies in a better light.

Some note that the additional time will allow the impeachment managers to present more robust evidence to the Senate, making a stronger case for conviction. That very well may be true. But with Republican senators largely lining up behind complaints about the process instead of the substance, and with many raising concerns about the merits of impeaching a president who has already left office, it’s not clear how many could actually be swayed even by new evidence.

The second dynamic is related: Since the House passed the article of impeachment two weeks ago, GOP senators have been able to observe the consequences the 10 House Republicans who voted for impeachment are now facing. None of it looks particularly appealing. Those lawmakers are contending with new primary challengers and backlash from constituents and local Republican Party leaders.

Per the New York Times, “Nearly all of the House Republicans who voted to impeach Mr. Trump have either already been formally censured by local branches of the G.O.P., face upcoming censure votes or have been publicly scolded by local party leaders.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s allies in the House have targeted Republican Conference Chair Liz Cheney, pushing to remove her from her leadership position in retaliation for her support for impeachment. The House Republicans who split with Trump are also dealing with heightened security concerns in the aftermath of the vote.

Some, like Michigan freshman Rep. Peter Meijer, have invested in safety gear and are taking other precautions to avoid being vulnerable to attack. “Many of us are altering our routines, working to get body armor, which is a reimbursable purchase that we can make,” Meijer said on MSNBC after voting for impeachment. “It’s sad we have to get to that point. But our expectation is that someone may try to kill us.”

Security risks around the Capitol complex itself haven’t disappeared now that Biden has been inaugurated, either. The Associated Press reported yesterday that federal law enforcement officials are examining threats aimed at lawmakers ahead of Trump’s impeachment trial. Their worries include “ominous chatter about killing legislators or attacking them outside of the U.S. Capitol.”

Thousands of National Guard troops will stay in Washington, D.C. to protect the Capitol as the Senate proceeds to the trial.

The Process

For the benefit of Uphill readers, the indefatigable Andrew Egger has spent some time digging into what the process will look like over the next couple of weeks:

In many ways, February’s impeachment trial will proceed along the same lines as Trump’s first session in the hot seat just over a year ago. The headache-inducing fight over “bifurcating” the schedule has been largely set aside, with key Republicans making clear they are opposed to dedicating any time to legislative business or Cabinet confirmations during the trial. Democrats will be able to confirm some of Biden’s nominees in the coming days, though, thanks to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s agreement with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell to delay the arguments until early February.

This may alleviate some of the time crunch, although the trial could still be dispatched in relatively short order: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi suggested late last week that Democrats may not deem it necessary to call witnesses, given that the acts for which the president was impeached took place in the public eye.

“We’re talking about two different things,” Pelosi told reporters Friday. With Trump’s first impeachment, she said, “we were talking about a phone call that the president had as one part of it, that people could say, ‘I need evidence.’ This year, the whole world bore witness to the president’s incitement, to the execution of his call to action, and the violence that was used.”

Trump has tapped South Carolina attorney Butch Bowers to lead his defense, and he will have the next two weeks to assemble arguments. Trump’s answer to the article of impeachment and the House impeachment managers’ pretrial brief are both due February 2, a week from today. Trump’s pretrial brief will follow on February 8, and the House managers will offer their rebuttal February 9.

The last time Trump was impeached, the presiding officer for the trial was Chief Justice John Roberts, but the Constitution makes that requirement only for trials of current presidents.

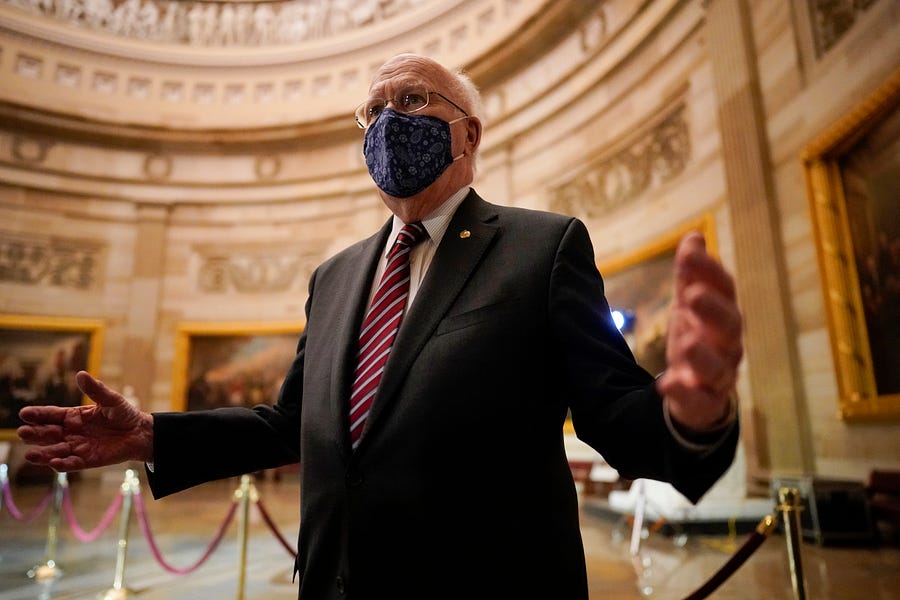

With Roberts out, that duty defaults to the president of the Senate, Vice President Kamala Harris. Since Democrats want to avoid the perception that Trump’s trial amounts to political revenge, Harris, too, is expected to step aside. The next person in line is the Senate’s president pro tempore—who by tradition is the longest-serving member of the majority party. When Republicans were in charge, that was Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley; as of last week, the role belongs to Vermont Sen. Patrick Leahy.

(Fun fact: Leahy has been in five Batman films.)

Ultimately, who presides over the trial is largely a symbolic matter: The Senate sets its own impeachment rules, and while the presiding officer is charged with interpreting those parameters, his pronouncements at the trial can be overruled by a majority vote. But just because the role is symbolic doesn’t mean the question of who occupies it will be unimportant at trial.

Republicans so far have signaled they are likely to couch their defenses of the former president in procedural terms rather than defending his conduct on the merits. In particular, some GOP senators have questioned whether it is constitutional for presidents to be impeached and tried after they have left office.

Trump’s legal team could lean into this skepticism by kicking the trial off with motions to replace Leahy with Roberts, experts tell The Dispatch.

“How I would expect this to play out is that the Senate will not ask the chief justice to preside, the trial will start, and one of the very first motions that the Trump defense team will make is a motion to require that the chief justice appear as the presiding officer,” said Keith Whittington, a constitutional law professor at Princeton University. Such a motion would have two goals: “to both delegitimize the trial on the grounds that it’s procedurally defective because it does not include the chief justice, and to try to maneuver the chief justice into issuing some kind of statement questioning the legitimacy of the trial.”

With a few exceptions, legal experts across the political spectrum are generally in agreement that impeaching and trying a former president is constitutional, as one of the two possible penalties for impeachment is disqualification from holding future office. What would be the point of such a power, they argue, if a president could escape that punishment simply by resigning?

On Monday, Schumer made that argument himself from the Senate floor.

“Some of my Republican colleagues have latched onto a fringe legal theory that the Senate does not have the constitutional power to hold a trial because Donald Trump is no longer in office,” he said.

“It makes no sense whatsoever that a president—or any official—could commit a heinous crime against our country and then defeat Congress’ impeachment powers by simply resigning, so as to avoid accountability and a vote to disqualify them from future office.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.