When the history of 2020 is written decades from now, the COVID-19 pandemic will of course loom large for its effects on the health and wellbeing of civilians around the work. But that’s not the only reason. The health crisis has also further exposed the fault lines in the so-called “great power competition” between the U.S. and China.

Among the most pressing issues: The ability to control—or at least steer—global institutions to advance national interests. It’s a battle that China, for a variety of reasons, is currently fighting, presenting the Trump administration with an important dilemma. Does the United States continue to work within the framework of existing global institutions, however flawed or corrupt, to extend its influence around the world? Or does the U.S. instead decide to abandon institutions it sees as hopelessly problematic?

President Trump is often dismissive, if not outright contemptuous, of alliances and international institutions. Some of his critiques have merit, even if the way he expresses his misgivings can be objectionable. But it’s one thing to argue that the prevailing institutions are inadequate and quite another to establish alternatives.

Since 2017, I’ve spoken with several senior administration officials who have independently come to the same conclusion: Trump has a short-term, transactional view of foreign affairs, one that is not conducive to developing long-term institutions or solutions. You could easily come to this same conclusion by observing the president’s public behavior.

The Chinese government, dominated by Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is quite obviously thinking long-term. Many of the CCP’s plans will probably not work out, but Xi’s subordinates are attempting to shift the global board in their favor. So even if most of their plans fail, the communist party will have enough pieces to continue playing. Despite its own obvious shortcomings in handling COVID-19, Xi’s lieutenants are using the crisis aggressively to cast their regime as a responsible world leader.

The U.S. government has been resisting the CCP’s machinations, but recent events reveal just how much work lays ahead. The wrangling over the World Health Organization (WHO) and its performance during the pandemic offers one clear example.

Trump halts funding for the World Health Organization.

On Tuesday, President Trump announced that the U.S. is halting funding for the WHO while his administration reviews its performance. The move comes after WHO officials regurgitated the Chinese line on coronavirus for weeks. One WHO tweet on January 14 has come to symbolize all that is wrong with the organization’s leadership, stating that “Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission” with respect to the coronavirus. There were many reasons to doubt the veracity of the Chinese claims. Taiwanese officials told the Financial Timesthat they’d warned the WHO about human-to-human transmission more than two weeks earlier, back in late December.

Of course, President Trump himself praised China and President Xi’s performance repeatedly as the threat from the virus grew. “China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus,” Trump tweeted on January 24. “The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency. It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American People, I want to thank President Xi!” Trump also praised Xi on February 7, saying: “Great discipline is taking place in China, as President Xi strongly leads what will be a very successful operation. We are working closely with China to help!” And on February 18, Trump said: “Look, I know this: President Xi loves the people of China. He loves his country. And he’s doing a very good job with a very, very tough situation.”

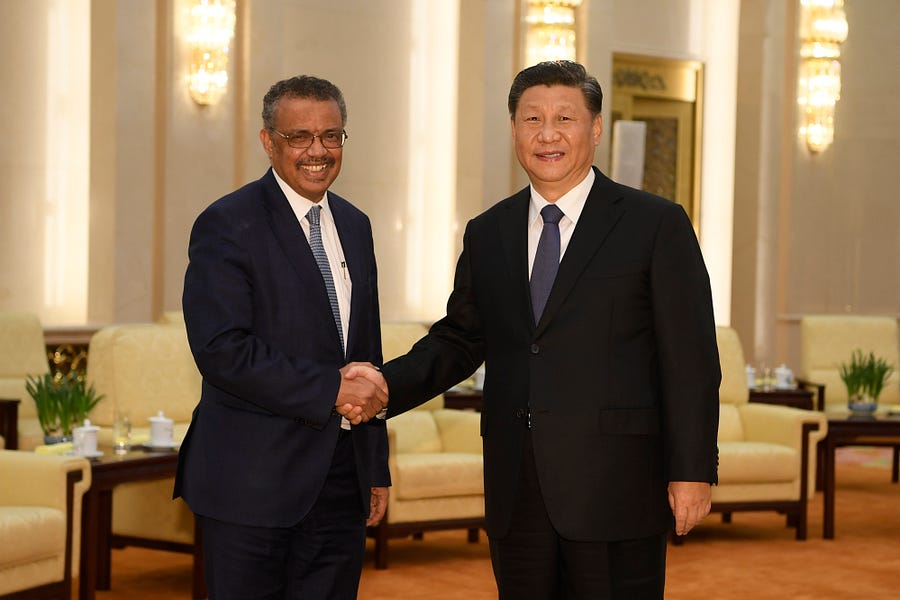

So, the WHO and its director, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, weren’t the only ones who accepted the CCP’s assurances at face value. Don’t get me wrong, the WHO director’s performance deserves significant public scrutiny. He has been especially deferential to the CCP. But he wasn’t the sole, gullible victim of China’s disinformation campaign. And Trump’s decision to blame the WHO is certainly self-serving, as he clearly mishandled the first weeks of the crisis himself.

Still, the U.S. has reasonable concerns about China’s role in the WHO now. The U.S. government already has leverage to mitigate the CCP’s nefarious influence at the WHO, but the Trump administration hasn’t used it. The U.S. is the “single largest contributor to the WHO,” according to a summary by the Kaiser Family Foundation. The U.S. government makes both voluntary and assessed contributions to the WHO each year. These donations totaled $513 million in 2017 alone. But it seems clear that the Trump administration hasn’t been exercising the influence these funds should command.

The WHO’s board consists of 34 members representing nations around the globe—from smaller countries to powerhouses such as China. The WHO’s website shows that 33 of these seats are filled. The sole vacancy? America’s chair. The entry for the United States of America from 2018 onward says only that the named representative is “To be communicated.” The Kingdom of Eswatini in Southern Africa, with an estimated population of just more than 1 million people, has successfully filled its chair during the Trump years. It wasn’t until mid-March 2020—in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic—that President Trump nominated Brett Giroir, a senior official at the Department for Health and Human Services (HHS), to serve on the WHO’s board. Why did it take so long? That’s not entirely clear. But at the very least, the long vacancy suggests that the Trump administration felt little to no urgency in the matter—that is, until the coronavirus pandemic swept the globe.

It is totally appropriate for Americans to question what their government has been paying for at the WHO. The U.S. government can and sometimes does reassess aid, even in times of relative calm. But the bigger question here is simple: To what end? Either the U.S. embraces its role as a global leader, and then demands accountability from itself and others, or it risks ceding the field to the CCP and other bad actors. Without an American-led WHO, you can bet there will be a Chinese-led WHO, which will only further the CCP’s soft power campaign around the globe. So, while cutting off aid to the WHO may feel like the right decision in the short-term, there are downsides to the move. And the bigger question is: How does the U.S. want the WHO, or something like it, to function going forward?

Russians defend China-WHO relationship.

The fight over the WHO doesn’t just pit the U.S. vs. China. One of the subplots in the coronavirus pandemic centers on the relationship between Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China. With some minor exceptions, Russian authorities have rhetorically backed their Chinese counterparts throughout the controversy—as has the Russian media. On April 12, the Russian Foreign Ministry released a statement decrying “attempts of some states to shift responsibility to others for the worsening epidemiological situation within their borders.” The statement didn’t take long to clear up any ambiguity about its meaning. “We believe that this is how the recent high-profile accusations by the US leadership against the World Health Organization should be assessed,” the statement continued. The Russian Foreign Ministry defended the WHO’s performance, arguing the organization “acted within its mandate, in strict accordance with the guidelines of member states and based on available scientific data.”

It’s hard to imagine that anyone with access to abundant public reporting on the WHO and coronavirus could really believe that. But the statement was intended to provide cover for the Chinese—not to accurately assess the WHO’s reported shortcomings.

The CCP was pleased with the Russian Foreign Ministry’s proactive defense of the WHO, which was shared on Facebook and other social media channels. During a press conference with China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian on April 13, Chinese television led off the questioning with a softball—reading directly from the Russians’ statement.

“Russia has expressed an objective and fair position. China commends that,” Zhao responded. Zhao went on to portray China as the true international leader, chastising the U.S. for allegedly “politicizing anti-pandemic cooperation and shifting blame to others.” He claimed that the WHO “has upheld an objective, scientific and just position, actively performed its duties, and played an important role in assisting countries in responding to the pandemic and promoting international anti-pandemic cooperation.” China “will continue to work with the international community, including Russia, to support WHO’s continued leadership in global anti-pandemic cooperation,” Zhao declared. (Zhao, it’s worth noting, is the same high-ranking Chinese official who floated conspiracy theories that the U.S. Army brought the virus to China.)

That, at least, is how China wants its efforts to be perceived. And the CCP is attempting to parry the Trump administration’s attack on the WHO’s credibility during the COVID-19 pandemic to position itself as the supposedly responsible global leader—facts be damned. Again, the question arises: How does the U.S. want the WHO, or something like it, to function in the future?

United Nations secretary-general criticizes decision to withdraw WHO funding.

The United Nations has decried the Trump administration’s decision as well. This is unsurprising given the WHO’s place within the United Nations’ system. “It is my belief that the World Health Organization must be supported, as it is absolutely critical to the world’s efforts to win the war against COVID-19,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said in a statement on April 14. Guterres at least left the door open for some accountability in the future—possibly—regarding how the virus first broke out in China. But the U.N. secretary-general had nothing to say about the WHO’s missteps, many of which can traced back to CCP mis-or-disinformation.

The U.N. and WHO also released a talking points memo that is intended to defend the WHO’s role during this time of crisis. The memo makes some valid points about the organization’s work on the ground, of course, but it also trumpets the WHO’s role in “providing accurate information” and “busting dangerous myths.” This is more than a little tone deaf. The biggest myth about the coronavirus thus far was that it couldn’t be transferred human-to-human. This CCP myth was endorsed and amplified by the WHO at a time when lives were on the line and could’ve been saved.

U.S. senators object to appointment of Chinese official to U.N. Human Rights Council.

Meanwhile, the U.N. has another China-related crisis brewing. On April 8, seven Republican sent a letter to Guterres decrying the appointment of Jiang Duan to the U.N. Human Rights Council Consultative Group. Jiang is currently the Minister of the Chinese Mission in Geneva. The Republican senators objected on the grounds that the CCP misled the world during the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak and has committed various human rights abuses, including in Xinjiang province, where the Uighur Muslim community lives under the constant surveillance of Xi’s authoritarian minders. More than 1 million Uighurs and others have been held in Maoist-style re-education camps. The senators point out that as a member of the human rights council, Jiang will have a say in “picking at least 17 human rights investigators, including those who look at freedom of speech, enforced disappearance, and arbitrary detention, rights abuses which the Chinese regime routinely perpetrates.”

The human rights council has a long history of enabling authoritarian governments, which have repeatedly held positions within the body. In June 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley announced that America was withdrawing from the council. Haley offered a compelling explanation for why this move was justified, especially after her efforts to reform the council had failed. Just as with America’s reassessment of its support for the WHO, the decision to withdraw from the U.N.’s human rights council was justifiable and even necessary given that body’s various pathologies. Both Pompeo and Haley emphasized that the U.S. would continue to play a leadership role with respect to human rights. But in practice, the administration hasn’t implemented an effective alternative or articulated a vision for one in the future.

Naturally, the CCP denies all wrongdoing. Zhao deflected this week, claiming that the U.S. withdrew from the council because of its own supposedly “notorious human rights record.” He then recounted a laundry list of America’s societal ills, blasting the “anti-China US lawmakers” for “poking their nose into the election rules of the UN agency.” Zhao also dismissed reports that Africans living Guangdong and elsewhere have been discriminated against, especially with respect to medical care during the pandemic. The U.S. State Department had highlighted such reports as part of the war of words between the two nations.

“China: Undercover” disproves China’s denials.

China’s denials on human rights are self-serving and not credible. Earlier this month, PBS’s Frontline aired its investigation into the treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang. “China: Undercover” is a chilling exposé, which opens with the scene of a man trying to contact his wife, who has been detained by authorities. The man, who lives outside of China, travels to the country’s border, where he then contacts a liaison via a burner cellphone. Speaking in code, the middleman quickly makes it clear that the man’s wife is still under the CCP’s thumb. The terse conversation ends with little hope of a reunion anytime soon.

One unnerving detail after another is revealed as the documentary unfolds from there. The homes of Uighurs are adorned with digital barcodes, which the authorities use to track potential dissidents or families deemed security liabilities. Men and women are graded according to their supposed fealty to the system. Indeed, Xinjiang is a laboratory for the CCP’s notorious social credit system, which is used to enforce obedience and codes of conduct, with surveillance technology monitoring virtually every step taken by the province’s citizens.

The CCP’s denials simply don’t square with the raw footage and firsthand testimony given in “China: Undercover.” But don’t expect the U.N.’s Human Rights Council to get to the bottom of the matter—with or without Jiang reserving a seat.

China has made clear that coopting international institutions is a key part of its strategy to expand its power. If the Trump administration doesn’t want to fight China’s growing influence inside those global bureaucracies, it’ll have to devise a strategy for building a new system of international institutions to thwart China’s ambitions and advance U.S. interests. That’ll require the kind of long-term thinking that, to be generous, hasn’t been a hallmark of the Trump presidency thus far.

Photograph of Xi Jinping and Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus by Naohiko Hatta, Pool/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.