Each year, the heads of America’s main intelligence and law enforcement agencies testify at “Worldwide Threat Assessment” hearings hosted by both the House and Senate Intelligence Committees. It is not often that the American public gets to hear from the men and women in charge of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), the CIA, the FBI, the National Security Agency (NSA) and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) in one forum. The annual hearings typically bring together those officials, as well as others, to testify about threats to U.S. security and how they plan to address them. However, this year’s hearings have been delayed, likely due to President Trump’s antagonistic relationship with parts of the intelligence bureaucracy—or, depending on how you look at it, the bureaucracy’s opposition to Trump and his policies.

Democrats in charge of the House Intelligence Committee requested that the hearings be held on Feb. 12. But the Intelligence Community (IC) heads were reluctant to testify this month. According to CBS News, officials complained that the open forum may subject them “to politicized inquiries from lawmakers and criticism from the president.” Indeed, the aftermath of last year’s hearings was especially contentious.

The ODNI’s written Worldwide Threat Assessment for 2019 critiqued President Trump’s America First policies, arguing that “some U.S. allies and partners are seeking greater independence from Washington in response to their perceptions of changing U.S. policies on security and trade.” Another passage in the analysis blamed the strengthening ties between China and Russia, in part, on American “unilateralism,” as well as “interventionism and Western promotion of democratic values and human rights.” In addition, Dan Coats, then the director of national intelligence, seemingly drew into question the efficacy of Trump’s policies with respect to both Iran and North Korea. On North Korea, Coats and the ODNI said it was unlikely Kim Jong-un would forsake his nuclear arsenal regardless of whatever concessions he extracted via diplomacy. Coats also suggested that the Iranian nuclear threat wasn’t as pressing as Trump claimed when he pulled out of President Obama’s nuclear accord with the Iranian regime.

President Trump noticed. On January 30, 2019, the day after the hearings, Trump harshly criticized the proceedings on Twitter, claiming that intelligence officials were being “extremely passive and naïve when it comes to the dangers of Iran.” He defended his decision to back out of Obama’s nuclear deal with the Iranians, arguing that the economic damage done to the regime by American sanctions and other measures were “the only thing holding them back” from being more aggressive throughout the Middle East and elsewhere.

Compounding these issues, especially during this year’s presidential election season, there’s the hotly contested intelligence on Russian interference in America’s elections. There’s already a bitter debate over the Russians’ intentions—whether they attempt to interfere on Trump’s behalf, or in favor of Bernie Sanders, or both. Or perhaps the Russians just want to add to the divisiveness that already exists in American politics. And there are also political disagreements over how effective Russia’s efforts really are. You can see how the 2020 hearings could quickly lead to another string of angry tweets from Trump. On top of all of that, there’s a new acting DNI, Richard Grenell, a Trump loyalist who has been on the job for only a matter of days.

Given the current poisonous climate, a friend in the intelligence world recently asked me if I think it really matters whether these sessions are held at all. I do—even if politics are likely to color the testimony. The American right and left should both care about oversight, even though they have competing agendas and different interpretations of what that means.

The ODNI’s budget request for fiscal year 2021 is $61.9 billion. While that figure pales in comparison to the more than $700 billion allocated for defense spending, those funds are enough to support a sprawling bureaucracy stretching across 16 intelligence agencies. Although imperfect, the Worldwide Threat Assessment hearings provide a measure of accountability—a rare opportunity for elected representatives to question the figures responsible for overseeing crucial functions of the U.S. government. That’s one reason the proceedings should still be held, regardless of any political squabbling.

Here is another reason: Close watchers will likely learn something new about China, Russia, the jihadist threat and other vital national security issues during the hearings.

Previous revelations concerning Osama bin Laden’s files, AQSL in Iran, and more.

I’ve been covering these proceedings for years and intended to do a write-up for Vital Interests. Alas, that will have to wait. But if the past is any guide, the testimony will contain some interesting revelations—including on topics that aren’t likely to garner much mainstream press.

For example, in 2013, the hearings revealed crucial details concerning Osama bin Laden’s library—that is, the hundreds of thousands of documents and files recovered during the May 2011 raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan. During the House Intelligence Committee’s Worldwide Threat Assessment hearing that year, then DNI James Clapper testified that the IC’s analysis of bin Laden’s cache led to “at least 400, over 400 intelligence reports … in the initial aftermath immediately after the raid.” These reports dealt primarily with the “immediate threats” that were identified in bin Laden’s files. In other words, Osama bin Laden was an active manager, a leader for thousands of terrorists across multiple countries.

Although few realized it at the time, Clapper’s testimony directly contradicted the words of other Obama officials, including then CIA Director John Brennan. Some Obama officials, including Brennan, sought to downplay bin Laden’s role in the months leading up to his death, arguing that he struggled to communicate with the outside world. This may seem curious, as the killing of bin Laden was arguably Obama’s greatest accomplishment as commander in chief. But in 2011 and 2012, the Obama administration was attempting to “end” the 9/11 wars. And the best way to do that, from their perspective, was to portray al-Qaeda and jihadism as a spent force. Obama’s argument hinged on the idea that nearly all of the jihadist groups fighting throughout the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia were really just “local” threats. These organizations, some of which were al-Qaeda “affiliates,” were supposedly disconnected from the al-Qaeda “core” leaders who attacked America on 9/11. This is same thinking that led to Obama’s flippant remark about ISIS being the “jayvee” of terrorism. The Obama administration’s theory of jihadism held that none of these other terrorists really required significant American attention, because they weren’t really part of a cohesive international organization or movement. Osama bin Laden was dead, General Motors was alive, and the 9/11 wars could be “ended.”

Properly assessed, Osama bin Laden’s files greatly complicated the Obama administration’s policy desires. Bin Laden wasn’t just watching Al Jazeera, as some commentators still claim. He was managing a worldwide network of terrorists, some of whom already threatened American interests at the time of his death. Again, the conventional wisdom in Obama’s DC held that there was a clear dividing line between al-Qaeda’s “core” (namely, Osama bin Laden and his lieutenants) and the “affiliates” outside of South Asia. In the years since Clapper’s testimony, we’ve been able to examine many of bin Laden’s files for ourselves. The documents include extensive communications between bin Laden and al-Qaeda groups in Iraq, Somalia, West Africa, and Yemen, as well as commanders in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He most certainly wasn’t “a lion in winter,” as the Obama White House led the Washington Post’s David Ignatius to believe.

In coming issues of Vital Interests, I hope to share with readers some additional observations on bin Laden’s library. As some readers likely already know, Steve Hayes and I advocated for the release of nearly all the files. In 2017, the CIA posted the overwhelming majority of them online. I’ve been combing through bin Laden’s memos and letters on and off since then. And I’ve been compiling a timeline of the last year of bin Laden’s life based on those same files. Hopefully, I’ll be able to share the fruits of this research in the future.

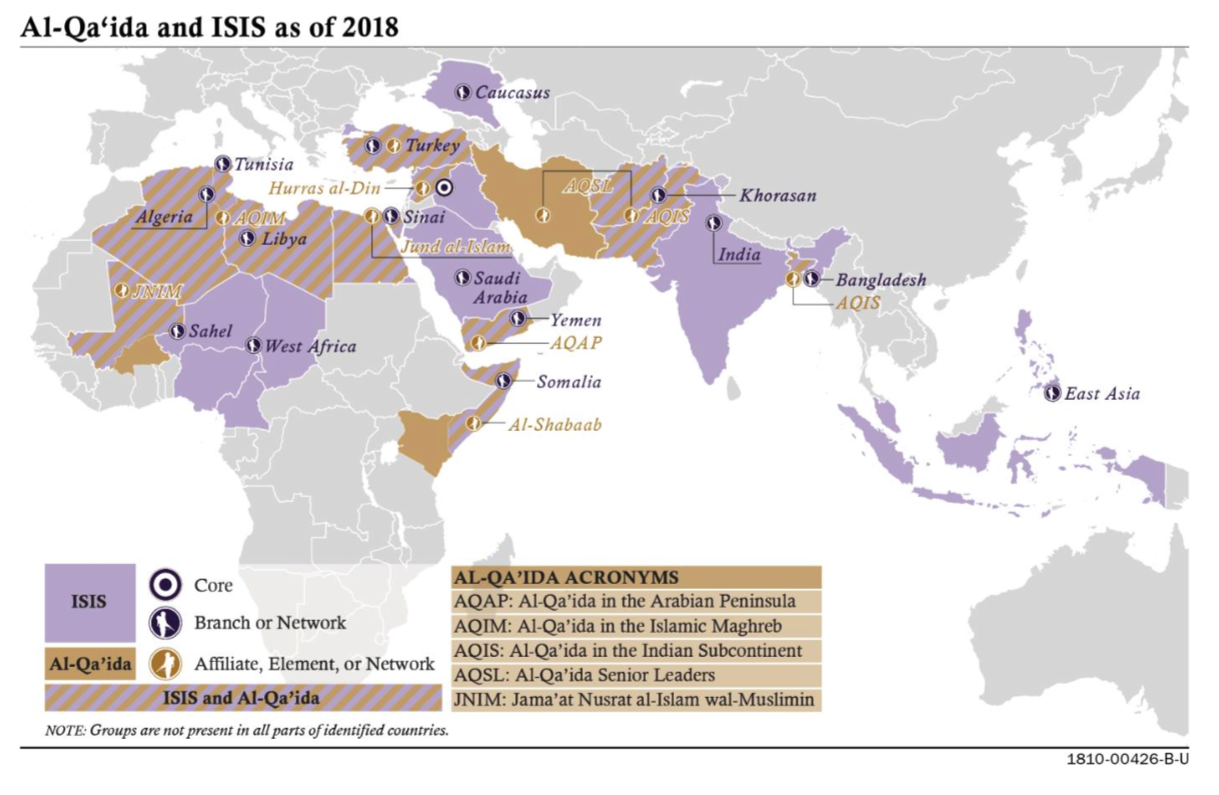

Back to the Worldwide Threat Assessment hearings—and the revelations contained therein. Last year, the ODNI produced an intriguing map showing the global footprint of both al-Qaeda and ISIS. The map is reproduced below:

If one is not careful, the map can be a bit misleading, because the jihadists don’t control or operate throughout the entirety of the countries that are shaded in. That’s the meaning behind the note in the bottom left hand corner of the map: “Groups are not present in all parts of identified countries.” For example, ISIS likely has some sort of presence in India, but it doesn’t have robust operations across all of the country, as the map could seem to indicate. The same goes for Saudi Arabia and the Caucasus, as well as other countries. But the map does underscore, in general, the scope of the jihadist threat.

Now, look carefully at Iran. You’ll notice the ODNI put in a bracket pointing to the presence of “AQSL” (that is, al-Qaeda’s senior leadership) in Afghanistan/Pakistan AND Iran. That’s significant.

For years, some in Clapper’s ODNI downplayed al-Qaeda’s presence in Iran. ODNI officials repeatedly told Steve and me that there was nothing to see here. But just last year, the ODNI itself recognized that “AQSL” has a contingent in Iran. The ODNI isn’t the only institution that has reported on AQSL’s Iran-based network. The United Nations has pointed to two senior al-Qaeda leaders, in particular, who are managing operations from inside the mullahs’ country. This is in addition to a series of terrorist designations and other official statements issued by the Obama administration’s Treasury and State Departments. Those Obama-era terrorist designations revealed that the Iranian regime hosts al-Qaeda’s “core facilitation pipeline.” Without the Worldwide Threat Assessment hearings, however, we may not have known that the ODNI itself now thinks AQSL’s operations in Iran are noteworthy.

Suggested questions for this year’s hearings:

Of course, AQSL in Iran was not the main focus of the ODNI’s written testimony last year. The map above included that nugget, but much of the testimony was devoted to other matters. Still, the bottom line for me is this: Without the Worldwide Threat Assessment hearings, we may not have the opportunity to learn what the U.S. IC thinks about al-Qaeda, ISIS and related topics—at least not in a formal way.

Consider three issues that should be covered at this year’s hearings.

Do the ODNI and CIA think the Taliban will truly break with al-Qaeda, as the State Department has promised?

Here’s a little tidbit I’ve learned in recent weeks: Senior U.S. intelligence analysts don’t think the State Department’s deal with the Taliban will lead to peace, or a true break between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

As readers of my work know, I’ve been critical of the State Department’s negotiations with the Taliban, mainly because America’s diplomats have been far too credulous, especially with respect to the Taliban’s supposed counterterrorism assurances. I get the American desire to leave Afghanistan behind. And true peace would be a blessing for the Afghans. But there’s no good reason to trust the Taliban. Even though the Taliban has been allied with al-Qaeda since the 1990s, the group has repeatedly lied about the relationship. Still, the State Department would have us believe that the Taliban is truly willing to break with al-Qaeda. This is supposed to be part of a bilateral withdrawal deal between the U.S. and Taliban that is slated to be signed at the end of the month.

But sources I trust say that official U.S. intelligence assessments undermine the rationale of the State Department’s proposed deal. There is considerable intelligence, I’m told, that no matter what the Taliban’s political office in Doha says, key Taliban personnel and leaders will remain al-Qaeda’s blood brothers. And they will seek to rebuild their Islamic emirate. Once again, take a look at the map produced by the ODNI for last year’s hearing. You’ll see that Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) is waging jihad on behalf of the Taliban, a fact that is also recognized elsewhere in the report. Lawmakers should be able to ask CIA director Gina Haspel what her agency has concluded regarding the Taliban’s willingness to forswear al-Qaeda. From what I’m hearing, the answers could cut against the State Department’s position.

What is the impact of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s death on ISIS’s cohesion?

President Trump approved the raid that led to Baghdadi’s demise in October 2019. Killing the terror chieftain was certainly an accomplishment for the U.S. Tens of thousands of men and women were loyal to Baghdadi. And his goons directed or inspired terrorism everywhere from the streets of Jakarta to Orlando. But it isn’t clear how much of an operational effect Baghdadi’s death has had on the one-time caliphate.

A report released by the Defense Department’s Inspector General office earlier this month suggests that the removal of Baghdadi from the battlefield may not have been all that damaging to his organization. U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) assesses that ISIS “remained cohesive, with an intact command and control structure, urban clandestine networks, and an insurgent presence in much of rural Syria” following Baghdadi’s death. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), which is usually represented at the Worldwide Threat Assessment hearings, came to a similar conclusion. Do the other intelligence agencies agree? And how robust is ISIS’s presence in not only Iraq and Syria, but also in jihadist hotspots such as Afghanistan?

Moreover, can the intelligence chiefs confirm the identity of Baghdadi’s successor? It has been widely reported that a veteran ideologue named Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla, also known as Hajji ‘Abdallah, has taken the reins of ISIS. I addressed the significance of those reports previously. Is the identification of Hajji ‘Abdallah accurate?

Was the terrorist responsible for the shooting at Naval Air Station Pensacola late last year really an AQAP sleeper agent?

On December 6, 2019, 2nd Lt. Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani (Al-Shamrani) of the Royal Saudi Air Force walked into a building at Naval Air Station Pensacola and opened fire. He murdered three U.S. sailors and wounded eight others before being shot and killed. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) quickly claimed “full responsibility” for the shooting, portraying Al-Shamrani as the group’s sleeper agent. What have the intelligence chiefs concluded regarding Al-Shamrani’s purported AQAP ties? Was he really a sleeper, implanted within America’s military bases to do AQAP’s bidding? Or was AQAP’s claim merely an opportunistic one?

Of course, there are many other topics to explore. China, Russia, the coronavirus, cyber threats—all of these and more will likely dominate the hearings.

Politics aside, the hearings offer a rare window into the thinking of America’s massive intelligence establishment. I know I’ll be watching if and when the sessions are finally held.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.