The annual inflation rate is creeping up, from 2.4 percent in May to 2.6 percent in June, holding well above the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. In normal times, that would worry Republicans facing midterm elections as the incumbent party with control of the White House, the House of Representatives, and the Senate.

But Republicans, being Republicans, are working hard to make things worse.

What is causing inflation to remain high and rise higher still? There are many factors at play. One of them is that Donald Trump and his Republican allies in Congress are pursuing pro-inflation policies, with the push-pull of tax cuts and tariffs putting more dollars into the marketplace to chase fewer goods, which is pretty much the classic formula for inflation.

Trump has inflated many things over the years—his assets on bank statements, his romantic résumé, his book sales—and inflation is the sort of thing that must come naturally to such a gasbag. Prices are already creeping up, with firms such as Adidas, Procter & Gamble, and Stanley Black & Decker announcing tariff-driven price increases. Groceries aren’t getting any cheaper, and neither is housing, the main driver of the late-summer uptick. But prices are getting higher across the marketplace, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics runs the numbers, finding higher prices for “household furnishings and operations, medical care, recreation, apparel, and personal care.” The few bright spots include used cars and airfares, which may indicate that people are simply putting off car purchases and skipping summer vacations under economic pressure.

Tariffs are a tax—let me emphasize here that Republicans’ key achievement in the Trump years has been the unconstitutional enactment of a national sales tax by the unilateral directive of president, without congressional authorization—and, as a tax, a big tariff should be anti-inflationary: The more money you pay in taxes, the less money you have to spend on cars and vacations and such.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Wanderland. You can read Kevin’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

But tariffs are an especially dumb and destructive kind of tax in that they do not produce a great deal of revenue in proportion to the economic distortion they introduce. Given that the tariffs are being implemented in parallel with what Republicans insist is “the largest tax cut in American history”—the cut-by-not-raising measure in their poorly conceived and idiotically named tax-and-spending bill—whatever counter-inflationary effect the tariffs might have had is likely to be overwhelmed by the inflationary effects of large cuts to other taxes, even if the extension of the 2017 cuts was far from unexpected. And here it is probably worth pointing out that Republicans are cutting taxes while running a deficit that is projected to be the third largest in American history.

So we end up with the inflationary effects from the tax cut with the supply-chain disruptions of the tariffs: more money chasing fewer goods.

Oof.

When we are trying to get a read on the health of the economy and on where it is going, one of the things we talk about is the real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate, meaning the GDP growth rate minus the inflation rate. If you have 3 percent nominal growth but 2.6 percent inflation, then you don’t have much growth at all; if you have 3 percent nominal growth and 3.5 percent inflation, then the economy is contracting in real terms. So inflation matters a great deal for how consumers feel in the here and now, but it also matters a great deal for how Americans are going to feel 30 years down the road. Today’s inflation is theft from tomorrow’s prosperity.

Let’s do some English-major math—as always, I encourage you to double-check my arithmetic and my sources, especially if you are skeptical of my conclusions.

From the turn of the century until the extraordinary COVID-19 period, inflation averaged 1.8 percent, just a smidge below the Fed’s 2 percent target. (The Fed likes 2 percent inflation on the theory that a tiny bit of inflation greases the economic wheels by giving consumers and businesses an economic disincentive to sit on their money forever and keeps us on the safe side of deflation, a hard-to-fix condition that can create powerful disincentives to consume or invest. I am enough of a cranky libertarian that I do not especially like the Fed’s theory of the case—I do not think that a policy of doubling prices every 36 years is harmless, and that is what 2 percent inflation does—but that is an argument for another time.) Our current inflation is not what it was in the immediate post-COVID period, but it is still high by historical standards: From January to June, it averaged 2.5 percent and was at 2.6 percent in June, the most recent month for which figures are available. Maybe 2.6 percent doesn’t look like a big increase relative to 2 percent, but it is 30 percent more.

In practical terms: If you invested $1 million today at a 7 percent nominal rate of return and 2 percent inflation, then you’d have a real return of 5 percent per year, giving you about $4.3 million at the end of 30 years. (I assumed annual compounding to keep it simple.) Raise the inflation rate to 2.6 percent and you lose about $700,000 in real returns over that same period, ending up with $3.6 million. (Moral of the story: Inflation stinks, but it is still pretty nice to have $1 million that you don’t need to touch for the next 30 years.) Inflation is a thief, but it is more like an embezzler than an armed robber: It steals more than many headline-generating economic crises do, but it steals quietly, without drama.

The math that holds true for personal investments also holds true for GDP growth. With 2.5 percent real GDP growth year-over-year, our $29 trillion economy becomes a $61 trillion economy in 30 years; at 2 percent, it is only a $53 trillion economy, meaning that we gave up $8 trillion in real GDP growth. Do you know what you could do with an extra $8 trillion a year in GDP? You could fund the entire federal government at 2024 levels with more than $1 trillion left over.

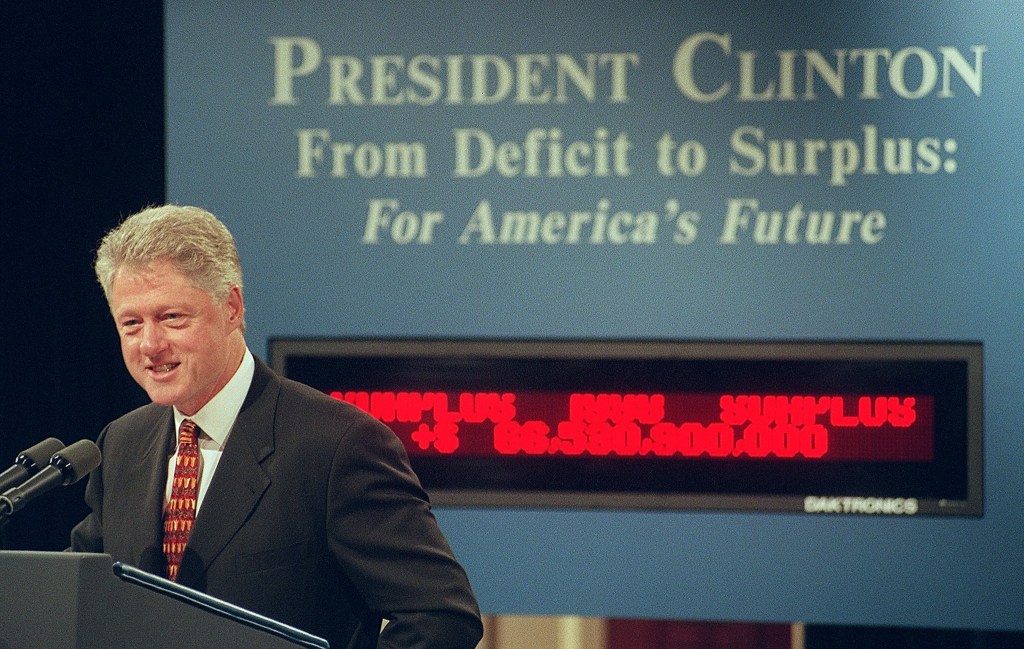

If you are a regular reader of this column, then you know I think the notion that presidents are somehow directly responsible for near-term economic performance is the real voodoo economics, but for illustration purposes, and since the politicians like to talk about it that way: If we started with today’s economy and had two choices—the real growth rate of the Clinton years (4 percent) or the real growth rate of the first Trump administration (2.6 percent)—the difference would be stark. At the Clinton rate, we’d have a $94 trillion economy in 30 years, but at the Trump rate, we’d have only a $57 trillion economy. The difference between the Clinton rate and the Trump rate would be $37 trillion in favor of Clinton.

Trump doesn’t like math like that: He just fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics because he didn’t like the jobs report, which is what you’d expect from the Walter Mitty of Joseph Stalins.

Caveats, caveats, caveats: Yes, the 1990s were awesome, and the unusually robust growth rate of the Clinton years was less the work of Bill Clinton than it was of Bill Gates, Marc Andreessen (he didn’t invent the internet, but his web browser made it usable), and a raft of entrepreneurs and venture capitalists who launched new firms and products that created immense wealth in that period. You’d think that some smart politician would be thinking to himself: “Hey, is there anything that we can do now to recapture some of that Clinton-era secret sauce?”

The 1990s were characterized by tons of investment, reasonably stable prices, expanding global trade and the integration of worldwide supply chains, relatively easy access to higher education and the consequent emergence of an educated work force with a reasonably high tolerance for risk, and, in politics, a mutual death grip that saw Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich cage-fighting their way to a small budget surplus produced by modest spending reforms and a significant but by no means radical tax increase. We cannot simply recreate the economic and political conditions of the 1990s afresh in 2025, but what Trump et al. are doing is trying to resurrect some of the worst economic ideas of the 19th century. I love John Quincy Adams, but if you’re producing a trade agenda in 2025 that he would more or less recognize, then you’re probably not thinking hard enough.

Words About Words

William F. Buckley Jr. once asked me for a vocabulary word, and I felt pretty good about that. The word in question was lapidary, which means “related to stonecutting” but is often used to describe a style of writing that is so lucid and precise that it seems like the sort of thing that ought to be engraved in stone.

I don’t suppose this hilariously illiterate marker put up by Eric Trump in tribute to his hilariously illiterate father qualifies as literally lapidary—I assume that is embossed metal, not engraved stone—but it is close enough. We could fairly call it monumentally stupid.

It is good to get a decent copy editor to look over your work before making it public, and that is especially important to do if you happen to be in the unfortunate situation of being stupid. The Trump boy packs a remarkable number of illiteracies into only a few words, among other things reporting that “it was his abiding love for Scotland – the ancestral home of his beloved mother, Mary Anne MacLeod – and the great game of golf, that inspired the team and I to build the New Course and complete what many believe to be The Greatest 36 Holes in the world,” moronic random capitalization and italics in the original.

That “inspired the team and I” boner is an example of overgeneralizing a common correction. When you are 3 years old, you might say, “Johnny and me went to the park,” and hear from your father, who cannot stop himself when it comes to that sort of thing, that what you meant to say is “Johnny and I went to the park.” And from that, many young people learn the wrong lesson, i.e., that the proper form is always “[name of other person] and I.” But it isn’t. “Me” is an objective pronoun, meaning a pronoun used to refer to someone to whom something is being done, whereas “I” is a subject pronoun, meaning the pronoun used to refer to someone who is doing something. You wouldn’t say, “Golf inspired I to take an interest in Scottish culture,” and, so, you also wouldn’t say “God inspired Johnny and I to take an interest in Scottish culture.” You’d say, “Golf inspired me [or inspired Johnny and me] to take an interest.”

I am always grateful to the editors who keep me from making dumb mistakes, which I do fairly often. Mistakes aren’t a big deal—if you write as much as I do, then you’re probably going to make some mistakes. (In years of editing Jay Nordlinger, I did not find a mistake in his grammar or usage, although I do remember having seen one ordinary typo. But Jay ain’t normal.) Making a mistake isn’t something to be embarrassed about: Making a plaque with your mistakes on it to display in a public area when you could have saved yourself some trouble by simply asking somebody with a better command of the language to look over your work before elevating your stupidity to monumental status—that’s something to be embarrassed by.

In Other Wordiness …

An eponym is someone or something after which something else is named. But sometimes an eponym has more than one association, which can lead to misunderstanding. For example, it is perfectly natural to read the words “German chocolate cake” and think that this is a formation like “Swiss cheese” or “Chinese checkers,” at which point you may start to wonder where exactly in Germany they are growing the coconuts that are the frosting’s defining ingredient. The dessert isn’t German at all—it is named for Samuel German, an English-American baker and the creator of German’s Sweet Chocolate, a baking chocolate. You may have heard someone correct you about “Canadian goose,” which is properly “Canada goose,” though it was not (as I had once assumed) named for a discoverer with the name “Canada,” like “Bell’s palsy” (for Charles Bell) or (Coenraad Jacob) Temminck’s tragopan, a kind of pheasant. The Canada goose is indeed named in honor of Canada, but the common name of Branta canadensis is Canada goose, not Canadian goose.

The Canada goose was catalogued by Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish naturalist who codified biology’s binomial nomenclature, the system by which species are designated by genus and species: Homo sapiens, Canis lupus, etc.

(If you have ever asked for a recommendation letter or book blurb, then you know how weird it can feel to ask people to write nice things about you. But people wrote some glowing things about Linnaeus: Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote of him, “I know no greater man on Earth”; Goethe judged, “With the exception of William Shakespeare and Baruch Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly.” Pretty good stuff as epitaphs go.)

It goes without saying that the false prince of all eponyms is English plumber Thomas Crapper, who did patent the floating ballcock associated with the modern flush toilet but whose name did not inspire the excretory word associated with it, a word that goes well back into Middle English.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here. My recent conversation with Adam Bellow is, I think, pretty fun.

In Closing

Today is the Feast of St. John Mary Vianney, who was known as the Curé d’Ars. He was a parish priest in Ars, France, and is the patron saint of parish priests. Parish priests are what Catholics call “secular” clergy, which may sound funny to the uninitiated ear—how could a priest be secular?—but the original meaning of secular is “in the world,” not, as we now sometimes use it, “irreligious.” A secular priest is a priest who belongs to a diocese, as opposed to a priest who belongs to a religious order such as the Society of Jesus or the Dominican Order.

One of the things for which the Curé d’Ars was known was his emphasis on confession and reconciliation, and I very much admire the fact that he (some of my Reformed friends may find the theology here a little hairy) constantly performed acts of penance on behalf of his parishioners, which is, from a certain point of view, probably the most literally Christian thing a man could do. We live in a time of relentless self-aggrandizement, from the president on down to every obscure social media poseur, and such a figure as St. John Vianney must seem increasingly strange to us. You will know that things are getting a little better when the Curé d’Ars seems a little less weird—and a lot better when he seems more like an example toward which to aspire.

I myself am not there yet—I do not exempt myself from any of the general criticism you’ll read in this column—and the most I could really say is not that I aspire to better things but that I aspire to aspire to better things.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.