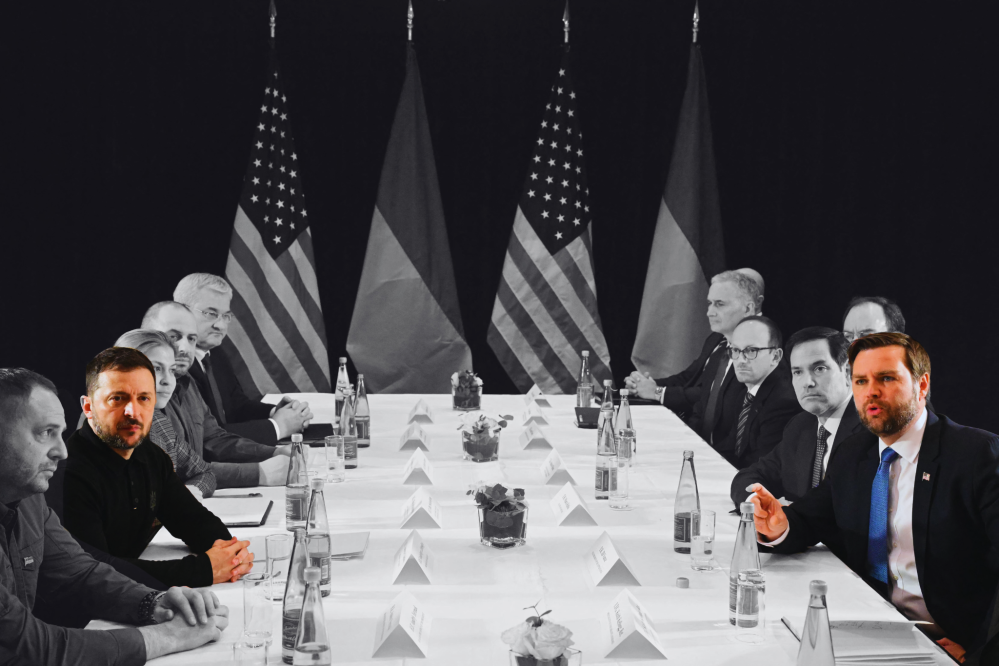

“I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or another,” J.D. Vance said in 2022 as he was running for the U.S. Senate. Now the vice president, he has been dispatched to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at Munich. And it just had to be Munich, didn’t it? Where better to surrender to a tyrant without a fight? Mnichovská zrada, the Czechs call it—the Betrayal at Munich.

But Donald Trump is no Neville Chamberlain—Chamberlain was an intelligent, accomplished, self-made man, and a patriot, albeit one who made a terrible error in judgment. He didn’t try to stage a coup when the British people voted him out in disgust.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who was possibly not drunk at the time, also weighed in earlier this week: Ukraine must hand over territory to the Russian invaders, NATO membership is off the table, and Ukraine cannot count on the United States for security guarantees. Zelensky knows what that means. “Security guarantees without America are not real security guarantees,” he told The Guardian in an interview. Hegseth is at the “clarifying” stage of this particular avalanche of baloney.

All of this is to say that Moscow is being rewarded for its brutality and aggression, while Ukraine is being punished for its petty and mulish insistence on surviving as a nation and a people. Vis-à-vis Moscow, the Trump administration is not even a paper tiger: A paper tiger might at least give you a papercut. Vance is also doing some clarifying and insisting that some of his earlier marks were misrepresented.

Ukraine is without very many friends in Republican politics now. Former Vice President Mike Pence—a knee-walking sycophant who believes that he should be forgiven for all he did to enable Trump for all those years because he grew a conscience in his last hours in power at precisely the moment doing so seemed most politically advantageous—managed to tweet: “Mr. President, Ukraine will only ‘be Russian someday’ if the United States abandons them to Putin’s brutal invasion. As you just said, ‘When America is Strong the World is at Peace.’ Stand Firm. If Ukraine falls, it will only be a matter of time until Russia invades a NATO ally our troops will be required to defend.”

Where to begin with this Mt. Everest of asininity?

Of course Ukraine will fail “if the United States abandons them to Putin’s brutal invasion”—what does the gentleman from Indiana believe is happening in front of his admittedly dim eyes? And the United States will be “required to defend” those NATO allies by a document that Trump holds in complete contempt. Everybody who has ever put his—or her—faith in Donald Trump knows what a promise is worth to him: There is no obligation, no matter how dutifully entered into, that he will not ignore. From every woman who has been stupid or greedy enough to marry him to a lot of small businesses that were foolish enough to do work or provide goods without payment in advance to practically every fool who ever lent him money, there is no excuse, at this point, for not knowing what Donald Trump is. And Pence knows—he just doesn’t have any attractive option other than pretending otherwise.

We should probably not look to Republicans to stand up for American interests here. The big energy right now among House Republicans is trying to put together bills providing, ex post facto, statutory justification for all of the illegal and unconstitutional stuff Trump is trying to do by means of executive fiat. Whether you think of that as trying to preserve the relevance of Article I or as providing window-dressing for a kind of soft administrative coup in progress will depend very strongly upon your assessment of House Republicans, who are … a mixed bunch. Expecting them to have the political skill and institutional will to change the president’s course on Ukraine would be to set yourself up for disappointment.

As admirable and courageous as the Ukrainians are, it is worth keeping in mind here that this is a question of American interests. The United States has critical national-security and economic interests that are threatened by an expansionist Russian empire, which, if Ukraine falls, will see Putin’s forces within spitting distance of Poland and invite similar aggression against the Baltics. Putin, like any other predator, will take the easiest route to his next meal. There’s a reason “Don’t Feed the Bears” is sound advice—and serious business—in bear country. And all of Europe is bear country now.

Economics for English Majors

The thing about Elon Musk and his blue-blazer clones taking a meat cleaver to the federal budget is that nobody is actually taking a meat cleaver to the federal budget. Republicans are getting ready to add about $4 trillion to the debt and are already resorting to parliamentary shenanigans—working on a nine-year budget baseline to avoid the Byrd rule, which places limits on long-term deficit increases. Republicans are planning to budget tax cuts for only eight years in order to understate their debt effect.

From the Committee for a Responsible Budget (CFRB):

The House Budget Committee released a proposed budget resolution for Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 today. The budget resolution includes reconciliation instructions that would allow up to $4.8 trillion in new spending and revenue reductions, at least $1.5 trillion in savings, and thus $3.3 trillion in new borrowing, or $4 trillion when accounting for interest. The budget also includes a non-binding policy statement setting a goal of $2 trillion of savings.

The budget resolution is through the 2034 budget window, which means that it would generally cover a nine-year period as opposed to the typical ten, and in order to comply with the Byrd rule prohibition on long-term deficit increases, it is likely lawmakers would enact most tax cuts for only 8 years. For these reasons, the annual allowed borrowing is larger than meets the eye.

The budget also assumes $2.6 trillion of savings from unrealistically high economic growth assumptions that are nearly certain not to materialize as a result of these policies and are well out of the range of outside estimates, which on average have found tax cut extensions would generate $213 billion of dynamic feedback, with the highest estimate being $581 billion.

As CFRB points out, we’re looking at spending nearly $90 trillion over the next decade, with another $20 trillion worth of goodies handed out indirectly through the tax code.

What Musk et al. are up to isn’t balancing the budget, or even putting the federal government on a more stable financial footing. It is pure Kulturkampf.

Words About Words

Check this out:

Half of all metro Bostonians now work at home via some digital link. 50% of all public education disseminated through accredited encoded pulses, absorb-able at home on couches. … One-third of those 50% of metro Bostonians who still leave home to work could work at home if they wished. And (get this) 94% of all … paid entertainment now absorbed at home ... an entertainment-market of sofas and eyes. Saying this is bad is like saying traffic is bad, or health-care surtaxes, or the hazards of annular fusion: nobody but Ludditic granola-crunching freaks would call bad what no one can imagine being without. But so very much private watching of customized screens behind drawn curtains in the dreamy familiarity of home. A floating no-space world of personal spectation.

A somewhat poetically rendered account of daily life in Anno Domini 2025? Yes, but it is from David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel, Infinite Jest.

In Other Wordiness ...

An accomplished military man of my acquaintance has for years quietly cringed every time someone says, “Thank you for your service.” It has become one of those rote, ritualistic things, and it is part of the post-9/11 militarization of American life and culture, something that actual soldiers and veterans have not always welcomed. But it is one thing when it is men and women who have faced death and danger on behalf of their country. It is another thing when—as in this recent advice column in Slate (a non-pornographic one, for a change of pace!)—an inquiry from a federal employee who may (or may not) lose his job received an answer that began with, I kid you not, “Thank you for your service.”

I am one of those odd-duck pro-bureaucracy libertarians. What I mean is that I do not want government to do much, but I want it to do what it does well, and that means having competent bureaucracy. Good bureaucracy instead of dysfunctional bureaucracy is a big important part of how you end up with a well-governed, orderly society. I don’t hate the bureaucrats, categorically. Goodness knows we need good ones, and the good ones should be treated with respect and compensated generously.

But they aren’t storming Omaha Beach. “Thank you for your service” seems like a lot.

And Furthermore …

You may know the Willi Schlamm line: “The problem with capitalism is capitalists. The problem with socialism is socialism.” True, true, true.

As I told a group of young journalists last week, the problem with journalism is journalists.

And the problem with poetry is poets. E.g.:

Poetry is not meant to be straightforward. Reading poetry is supposed to take effort. The problem is that we’ve become lazy readers and writers, and AI is profiting from that. The headaches of formality, connotation, meter, grammar, allusion and intention have caused us to discard our literary minds and trade them for convenience. But difficulty is the crux of poetry. ChatGPT will never be able to slyly admonish a critic mid-stanza, deliberate over the perfect phrasing with an editor or become struck with inspiration in the middle of personal tragedy.

Poets travel the nooks and crannies of their brains, negotiating their lived experiences, their sparks of inspiration and their heartfelt emotions. ChatGPT, on the other hand, is programmed to take the path of least resistance. It is a “stochastic parrot,” as some machine-learning researchers have put it. The words of ChatGPT don’t correspond to reality but to an algorithm linking words and phrases based on probability.

Poetry is meaningful because it is art created through adversity, from the unpredictable and unanticipated. We cannot expect to appreciate poetry without accepting that sometimes it leads us to places we don’t understand. Embracing the difficulty of the abstract—whether that’s through including T.S. Eliot in our curriculums or writing our own emails—is how we retain our humanity.

What an absolute crock, and a landslide of clichés and banality. Some poetry is cerebral and difficult; a great deal of great poetry was meant for people who can’t read and for societies that were largely illiterate—Homer, the psalms, Gilgamesh, etc. The work of turning poetry into a career, a kind of ersatz profession, is one of the reasons that books of poetry in our time are bought mainly by people who have written or are planning to write books of poetry of their own.

The aforementioned Mr. Eliot (“with his features of clerical cut”) had a job most of the time he was doing his main work, first at a bank and later in publishing. And one of the remarkable things about Eliot’s poetry, as it lurches between Dante and the Upanishads, is that readers cannot fail to notice how much the supposedly otherworldly Eliot lived in the world, in the smoke and smog and underground stations of London, in his memories of St. Louis, etc. His epigones, on the other hand, know about—what? MFA programs and the classrooms of third-rate colleges?

The problem with poetry is the poets. Once you have the idea in your head, you’ll keep seeing it proved and proved again.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

I’ve been in Texas for a talk at my alma (more or less) mater and some reporting and a few personal errands.

I’ve never been one of those yee-haw sentimental Texans, though I might get a little choked up if you ask me about San Jacinto or Sam Houston, and I might have more to say than you want to hear about Sonny Curtis or the Flatlanders. (Sonny Curtis wrote both “I Fought the Law” and “Love Is All Around”—that’s a man with some breadth.) I am very fond of my part of Texas, but it isn’t a hell of a lot different from eastern New Mexico or Oklahoma or southwestern Kansas. Texas exceptionalism is kind of a cult.

This is a happy time in my life, but the Llano Estacado is a place that also has a lot of less happy memories for me, but, still, driving across all that Big Empty is good for … I’m sure the Germans have a word for it: something that isn’t quite grief but probably ought to be and probably would be in someone who has a more normal emotional range than mine, something that would be regret if it weren’t so entirely pointless. And this is a good place for that—there’s enough room for it, whatever it is and whatever you call it.

I’m really suspicious of romantic notions about how we’re shaped by our youths and by the places we’re from, but all that real estate and that very low people-to-dirt ratio does leave an impression. There’s a great moment in Firefly when a space traveler talks about having been to the edge of the galaxy: “It just looked like … more space.” He tries to play it cool, but it is clear the memory is disturbing. (That character, Jayne, has the best lines, skillfully delivered with a nice balance of menace and charm by Adam Baldwin: “I’ll kill a man in a fair fight. Or if I think he’s gonna start a fair fight. Or if he bothers me. Or if there’s a woman. Or if I’m gettin’ paid. Mostly when I’m gettin’ paid.”)

If you want more space without actually going to space, take a drive through my corner of Texas—it’ll suit you. And if you have something you need to be alone with for a little bit, you could hardly do better.

The world and its doings will paint on any canvas that’s available, from Mayfair to Muleshoe, and these flat, empty places are wide open to receive their share of the historical record. None of these places will ever offer the fascination of Pompeii or a picturesque Greek ruin, but they attest to the passing of time—and consequential time at that—in their way. In a little Panhandle town I’ve driven through maybe a dozen times in the past ten years, there are a lot of shuttered businesses and vacant buildings—the brute force of modernity has hit some of these little places hard, but the COVID-19 pandemic hit them extra hard, wiping out a lot of retail and hospitality businesses.

For years, one boarded up storefront has had a handmade sign out front reading: “THIS TOO SHALL PASS.” And it’s still there, but somebody has painted a big red X over it. So, maybe it won’t pass. Maybe this is it. It is possible to lose faith in Stoicism, I suppose, or in the arc of history, or whatever it is people believe in that makes them put up signs like that.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.