January 6, 2021, was not a riot. It was not a protest, an insurrection, or a (failed) coup—at least, not exclusively so. None of those terms capture the exact nature of premeditated violence done for psychological effect to achieve political ends that characterized the violence at the U.S. Capitol that day. There is a better term, one that does precisely capture that mix: terrorism. January 6 was an attempted terrorist attack on the U.S. Congress. It is important that we call the attack by its rightful name to recognize the threat we face.

Americans seem uncertain about how to characterize January 6. In August, only 52 percent of Americans agreed it should be described as an act of terrorism, according to an NBC poll. That result is a decline from 57 percent in January, despite the additional information that has come to light since then about how many weapons the attackers carried and how much planning and premeditation took place before the attack. Most citizens are likely unaware of the new information and instead are responding emotionally: in January, it was fresh and seemed to merit a strong label; a year later, emotions have cooled.

Some leaders seem hesitant to name January 6 an attempted terrorist attack. In his inaugural address days after the attack, President Joe Biden warned of “a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat.” It took seven months, when recognizing the police who defended the Capitol, for him to unequivocally say that “a mob of extremists and terrorists launched a violent and deadly assault on the People’s House and the sacred ritual to certify a free and fair election.” Christopher Wray, the director of the FBI, called the attack domestic terrorism in testimony before Congress in June, but the FBI has not yet brought any terrorism charges against any of the more than 700 defendants currently standing trial—likely because of the difficulty of proving intent for any one specific defendant.

Some have been more straightforward. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi compared the January 6 attack to 9/11, saying both were attacks on U.S. democracy—one from within and one from without. Former President George W. Bush made a similar comparison on the anniversary of 9/11, suggesting an equivalence between jihadists and unnamed “violent extremists at home,” who share a “determination to defile national symbols.” Congress, for its part, seems to have no misconception. The Select Committee to Investigate the January 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol was created “to investigate and report upon the facts, circumstances, and causes relating to the January 6, 2021, domestic terrorist attack upon the United States Capitol Complex.”

Terrorism is, under U.S. law, “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” There is no question the January 6 attack, in which hundreds of people violently broke into the Capitol building to stop Congress from certifying the presidential election, fits that definition.

Some critics, like Wisconsin GOP Sen. Ron Johnson, insist January 6 was a “peaceful protest,” echoing 36 percent of Republicans who told pollsters in December that the event was “mostly peaceful.” That’s accurate only if we characterize the event by the actions of a numerical majority of people present on the National Mall. There may have been up to 120,000 people on the National Mall on January 6. A much smaller number—early estimates suggested about 8,000—converged on the Capitol complex around 1 p.m. Perhaps 1,200 entered the building illegally, of whom more than 700 have been identified and charged so far.

Most of the protesters on the Mall were peaceful, and even a majority of those at the Capitol did not illegally enter the building. But that is a little like saying 9/11 was mostly peaceful because a majority of New Yorkers were not murdered that day. It somehow misses what was distinctive and noteworthy that morning. Most people act peacefully and lawfully most of the time. But we’re rightly interested in what is unique and unusual behavior—which will be, by definition, a minority of people in a small amount of time—that has outsized influence and does disproportionate damage to public safety and democratic norms.

Nor was the attack on the Capitol a rally that accidentally got out of hand, an unplanned, spontaneous outpouring of frustration that went a little too far, as some have claimed. Though the full picture is still emerging, it is clear that law enforcement saw warnings, predictions, and threats of violence before January 6. A New York Times documentary shows how groups like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys seem to have played key roles instigating violence, coordinating movement, and spurring protesters to become rioters. Most of the protesters may not have intended to enter the building or engage in violence, but they allowed themselves to be used as cover for the leaders who did, and to be carried along by the mob mentality that took over.

And the attackers were armed. A small number carried guns; a much larger number carried “knives, axes, batons, tasers, bats, poles,” according to Politico, and pepper spray. “Others stole police shields and used metal barricades and furniture as makeshift weapons.” More than 150 Capitol police officers were wounded in the attack. By every piece of evidence that has come to light over the past year, January 6 was a premeditated violent attack by an armed group against the government. That is terrorism, plain and simple.

II.

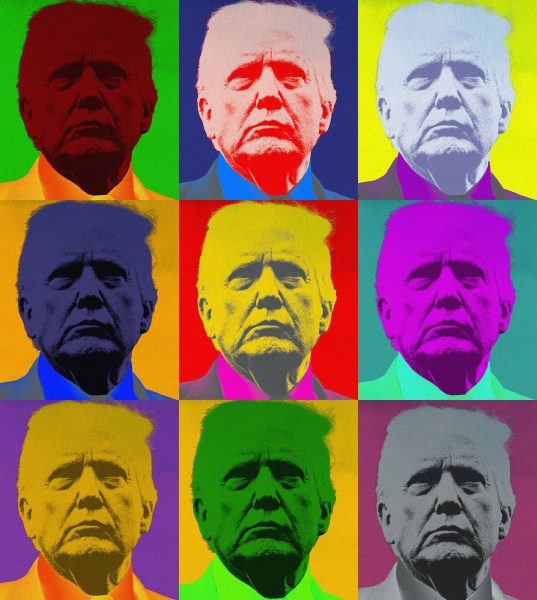

Why does it matter what we call the event? Because words matter, and because we have to recognize what Republicans are downplaying, mainstreaming, or ignoring. Seventy-eight percent of Democrats say the protesters who entered the Capitol were “mostly violent,” compared to 26 percent of Republicans, according to a Washington Post poll. The partisan divide tracks closely with views of former President Donald Trump and the 2020 election. Ninety-two percent of Democrats believe Trump bears “a great deal” or “a good amount” of responsibility for January 6, compared to 27 percent of Republicans. Eighty-eight percent of Democrats believe there is no evidence of widespread electoral irregularities in the 2020 election, compared to 62 percent of Republicans who believe there is. A similar number—almost 60 percent—of Republicans believe Biden was not legitimately elected.

Republicans and right-wing pundits have spent much of the past year downplaying January 6. Trump claimed that the “real insurrection” was November 3, 2020 (Election Day), and that January 6 was a day of justified protest against it. Tucker Carlson’s three-part Patriot Purge special on Fox Nation claimed the FBI’s arrests of January 6 attackers is a tyrannical manhunt akin to a “domestic war on terror.” In September, a small “Justice for J6” rally drew a small crowd of protesters who claimed the defendants had been arrested unjustly and were being treated unfairly.

The right is increasingly led by shills running cover for terrorists, sophists who fabricate ideological legitimacy for political violence so as to dangle the implied threat of its use in case the normal political process doesn’t go their way—all in the name of saving democracy. That prospect should frighten anyone familiar with the histories of Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Egypt—or any place in which sporadic political violence mixes with the political process.

Because the effort to excuse or justify terrorism in the name of democracy is not new. French Revolutionary leader Maximilian Robespierre told the French National Assembly in 1794:

If the mainspring of popular government in peacetime is virtue, amid revolution it is at the same time [both] virtue and terror: virtue, without which terror is fatal; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is nothing but prompt, severe, inflexible justice; it is therefore an emanation of virtue. It is less a special principle than a consequence of the general principle of democracy applied to our country’s most pressing needs.

Under the guise of “virtue” and “justice” violence that enforces the true will of the people is the legitimate servant of the common good. By such rhetorical gymnastics do terrorists claim violence serves democracy. No wonder January 6 apologists compare the day to the storming of the Bastille. No matter the merits of the specious analogy, it can hardly be considered conservative and almost certainly will not turn out well for democracy in America.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.