Can federal judges be members of legal organizations and still uphold their duty to be impartial? That’s a question the Committee on Codes of Conduct for the U.S. Judicial Conference seeks to answer.

The committee sets the ethical rules for judges and provides them with guidance documents. This is a useful enterprise and the committee generally exercises its duties well. Recently, however, it released a draft opinion stating that judicial canons preclude judges from being members of the Federalist Society and the American Constitution Society, but do not preclude them from membership in the American Bar Association. The committee’s rationale for its preliminary ruling is misguided, to say the least.

The Federalist Society is an organization of lawyers and legal scholars who debate and discuss constitutional law. It was started in the 1980s by law students dissatisfied that their professors taught law through a progressive lens with a preference for using courts to achieve social change. They wanted more meaningful dialogue over things like the separation of powers, federalism, and the proper constitutional role of the federal judiciary. The Federalist Society grew quickly and has become a highly successful national association. Importantly, it never lobbies, never files briefs with courts, and never takes positions on cases or law. Instead, it pursues its ideas through debate and discussion, careful always to include all types of legal and judicial philosophies.

The American Constitution Society also seeks to bring lawyers and legal scholars together to discuss constitutional and legal issues. But it does so through a legal philosophy that is sympathetic to government power, that is less desirous of judicial federalism, and less formalistic in its interpretation of the constitution than the Federalist Society. The American Bar Association is the professional advocacy group for the nation’s lawyers. It seeks to “advocate for the profession,” broadly defined, and has as one of its primary goals to “eliminate bias and enhance diversity.”

The Committee on Codes of Conduct recently determined that federal judges cannot be members of the Federalist Society or the ACS—but that they can be members of the ABA. According to the committee, a reasonable person might believe a judge who is a member of the Federalist Society or ACS is biased and cannot deliver impartial justice.

The committee’s ruling violates the constitution, wrongly caricatures the Federalist Society, and ignores the ABA’s clear biases.

To begin with, the committee’s proposed rule likely violates the Constitution. In Republican Party of Minnesota v. White (2002), the Supreme Court held that the government cannot limit speech by candidates for state judicial elections simply because that speech might create an appearance of “bias.” Surely, if the Constitution permits candidates for judicial office to take positions on policy issues, it must allow judges to become members of legal organizations that publicly debate and discuss constitutional law.

Moreover, the committee’s ipsie dixit characterization of the Federalist Society is contrary to the facts and contains no empirical support.

Despite acknowledging that the Federalist Society is not a political organization under the Code of Judicial Conduct—which automatically would preclude judicial membership—the committee nevertheless determined that a judge’s membership in the Federalist Society evinces “a predisposition as to legal issues.”

To determine that such membership would evidence a bias, the committee undertook the non-scientific task of … looking at the Federalist Society’s website. There, the Federalist Society calls itself a “group of conservatives and libertarians dedicated to reforming the current legal order.” The committee found this statement enough for a reasonable and informed public to believe that a member-judge would be biased against litigants.

The committee presents no data to support its claim that “reasonable and informed people” would believe such bias exists. Nothing. If the committee truly seeks to examine the issue of perceived bias, it should have collected some data to support its policy decision.

The committee went on to muckrake that the Federalist Society’s “funding comes substantially from sources that support conservative political causes.” Presumably this funding also would lead a reasonable observer to question a judge-member’s impartiality. But again, no data to support the claim. (And even if the committee analyzed such data, the relevance of the Federalist Society’s funding would seem to be irrelevant—or at least take a back seat to its actual track record of behavior.)

What is clear is that the Federalist Society involves speakers of all stripes. It reaches out to audiences across the board. Just the other day I attended a talk on free speech by the liberal activist Nadine Strossen. Who sponsored her talk? That hotbed of left-leaning radicalism, the Federalist Society.

Even assuming the committee was correct about the Federalist Society (which it is not), it ought to have applied the same standard to the ABA. It did not. Instead, the committee elided the bias clearly shown by the American Bar Association. The committee privileges the ABA because “its goals are clearly oriented toward the improvement of the law as a whole.” How this differs from the ultimate goals of the Federalist Society or the ACS is unclear. After all, those groups also want to improve the law.

At any rate, the ABA is, in reality, more biased even than the wrong-headed caricature of the Federalist Society. The ABA has a track record of advocating for liberal causes. Over the last 10 years, the ABA filed 31 amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs on the merits of cases at the Supreme Court. It supported one of the parties in 26 of those cases, and in fully 77 percent (20 out of 26) of its briefs supported the liberal position in the case. Among the six cases in which it supported the conservative position, two were patent cases and two were judicial power cases. Not the stuff of high stakes ideology. The Federalist Society, on the other hand, never files briefs and takes no positions on public policy.

What’s more, a recent empirical legal study examined the ABA’s ratings of federal judicial nominees and found that it systematically biases its rating against Republican nominees. The authors matched the nominees such that Republican nominees were identical to Democratic nominees in terms of sex, age, years of experience, and similar factors. They created a control group and a treatment group that were as similar as possible but for the treatment effect (the party of the president who nominated them). They found that “nomination by a Democrat increases the probability of receiving a Well Qualified rating by approximately 15 percent.” In other words, the ABA is significantly less likely to give Republican judicial nominees its highest rating than otherwise identical nominees of Democratic presidents. At the very least, this suggests a political bias among the ABA, one that has not been established to exist among the Federalist Society.

The treatment of the Federalist Society (and the American Constitution Society) is an important issue. It appears to many that some are trying to use the apparatus of the federal government to quell speech and associational rights based on bogus fears and a political agenda. That may be wrong. Perhaps the committee is well-intentioned. But until it meets even a threshold showing that its policy change is necessary, we should remain highly skeptical and ask the committee to retract its draft opinion.

Ryan J. Owens is the George C. and Carmella P. Edwards professor of American politics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the director of the Tommy G. Thompson Center on Public Leadership.

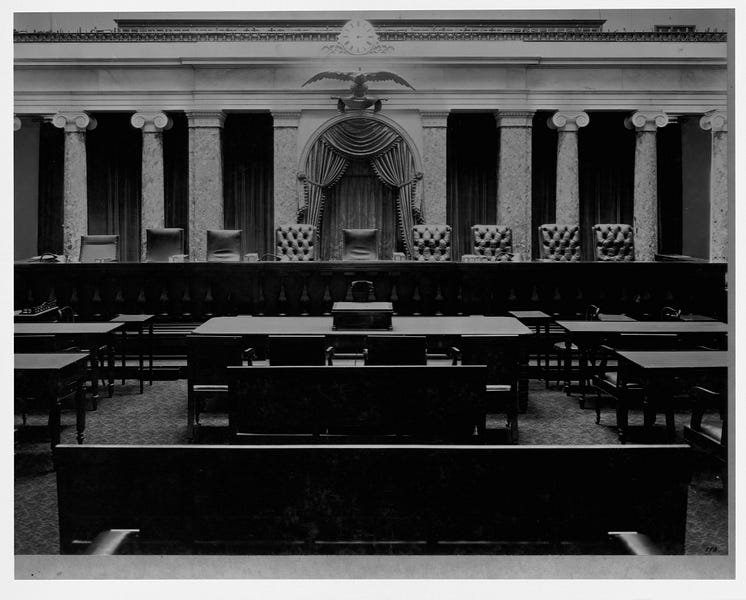

Photograph of the old Supreme Court room by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.