The push for schools to reopen seems to have reached critical mass. Conservative pundits have been banging this drum for months, but they’ve recently been joined by the likes of Jonathan Chait, Matt Bai, and even the New York Times and Washington Post editorial boards. President Biden has repeatedly pledged that “the majority” of schools should reopen during his first 100 days. Mike Bloomberg, former New York City mayor and Democratic presidential hopeful, insisted last week that “There’s no reason not to have schools open.” Truth is, Donald Trump’s departure seems to have sucked much of the partisanship out of the reopening debate.

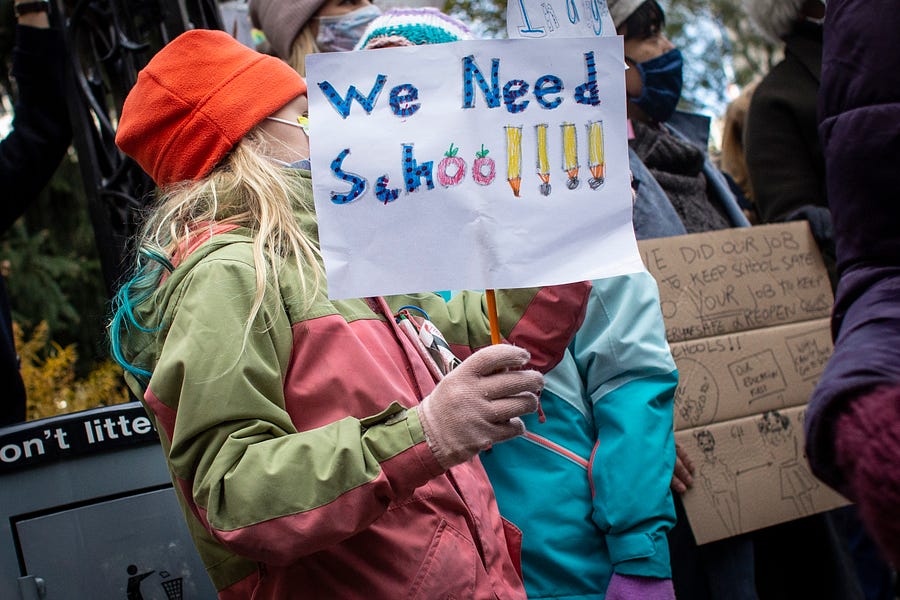

Meanwhile, tales of boiling parent frustration are legion. For months, communities have been dotted with signs urging local officials to “Reopen Our Schools.” Lately, the pleas are getting more aggressive. One recent viral video features a Virginia father railing that sanitation workers face more risk than anyone in the local schools and thundering to the Loudoun County board of education, “You’re a bunch of cowards hiding behind our children as an excuse to keep our schools closed.”

Indeed, the science is now pretty clear that the risks of reopening are modest. Two weeks ago, three CDC officials explained in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “As many schools have reopened for in-person instruction in some parts of the US … there has been little evidence that schools have contributed meaningfully to increased community transmission.” Dr. Anthony Fauci has noted, “The spread among children and from children is not really very big at all.” Biden’s new CDC director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, has said that “school settings do not result in rapid spread of COVID-19 when mitigation measures are followed” and even added that “vaccination of teachers is not a prerequisite for safely reopening schools.” And, of course, many private schools have been open since fall with little evidence of adverse impacts on public health. Meanwhile, the devastating social, emotional, academic, and economic costs of closure have become increasingly clear.

Yet, despite the diatribes and data, more than half of public school students remain fully remote. Worse, the Center on Reinventing Public Education reports, based on its school district tracker, that last fall’s gradual progress toward in-person learning has dissipated—with almost three-quarters of urban school districts once again shuttered. And, as the Associated Press reported Monday, plenty of local school boards and district officials are suggesting that schools may need to stay remote into fall or beyond.

What’s going on? After all, hardly anyone is saying, “We want schools to be closed!” Rather, they say, as National Education Association President Becky Pringle puts it: “No one wants to get back to in-person instruction more than educators—but we must do so safely.” Of course, that little word—“safely”—provides a lot of convenient wiggle room. If everyone is eager to reopen, though, and the science suggests that most schools can safely do so, what’s the issue?

Well, it’s something of a case study in Politics 101; the cost-benefit calculus for kids and communities may argue for reopening, but the calculus for public school officials looks quite different. For superintendents and school boards, reopening means angering teachers and staff, risking a high-profile COVID-19 infection, or being accused of racial insensitivity; right now, closure carries none of these risks. In short, whatever is in their hearts, public school leaders have institutional, professional reasons to slow-roll reopening. There are at least five key dynamics at work.

First, for all the op-eds and editorials urging schools to open and the growing frustration with virtual learning, most parents don’t appear to be angry with schools, teachers, or teachers unions. In fact, as of November, Education Next’s respected national survey of parents found that, even though 60 percent of parents say their children are learning less than they normally would, they seem generally content with their schools. The public continues to give schools high marks, with 61 percent giving schools in their community an A or B (up a bit from last year), and shows no evidence of turning on unions; in fact, Education Next reports that “parents seem to be viewing unions in a more favorable light.” Meanwhile, especially given that significant numbers of parents continue to say they’re nervous about sending their children back to school, the parental pressure to reopen is currently much less powerful than the punditry and science might lead one to expect.

Second, for many educators, returning to work is less appealing than the status quo. Right now, teachers working from home are earning the same salary and benefits as they would if schools were to reopen. Meanwhile, districts have shortened their workday, created asynchronous learning days that give teachers extra hours to plan and get things done, reduced formal supervision, eliminated commutes, and supplied technology, training, and troubleshooting to support teachers at home. Moreover, returning to in-person instruction may well entail teaching both students in the classroom and those viewing from home—a headache that no sane educator would relish. Practically speaking, from a teacher’s perspective, the status quo has a lot to recommend it, and gives teachers cause to support the unions even as they keep moving the goalposts for what constitutes a “safe” reopening.

Third, education officials have an appealing way to finesse this; they can stay closed while insisting they want to reopen by pleading poverty. That’s hardly out of character. (Heck, last May, New York City Chancellor Richard Carranza lamented his budget, telling city council members, “We are cutting the bone. There is no fat to cut, no meat to cut.” Carranza’s is one of the highest-spending school systems in the country — at $28,900 per student in 2019—and had added 340 positions to its bureaucracy the prior year.) Indeed, school leaders have an unlovely habit of suggesting that funding is in perpetual crisis. So, it’s no trick at all to explain that the $60-odd billion in 2020 federal COVID-19 aid wasn’t enough and that it’ll take much more to reopen safely. (As The Dispatch reported last week, much of this money has yet to be spent.) Here, superintendents stand shoulder-to-shoulder with NEA President Pringle, who’s said, “What we are trying to do is to make sure that the blame gets placed where it should be placed, and that is Congress that has failed to act.” For school district leaders, the choice between pressuring staff to return to work and explaining that they’d really, really like to reopen, but can’t do so safely until they get more money, is a no-brainer.

Fourth, district officials face enough practical headaches if they reopen that there’s a lot of incentive to “play it safe,” especially if the decision can be framed as careful rather than craven. These include ensuring adequate ventilation, crafting effective disinfectant policies, coordinating simultaneous in-person and remote learning, handling COVID-19 testing, figuring out how to address at-risk teachers and staff, planning for social distancing, and providing masks and PPE. It’s easy to understand why a district official might prefer not to have to manage all of that. And if reopening were to go awry, superintendents and school boards know there are union officials and reporters waiting to pounce. Thus, there’s a lot of incentive for school officials to keep issuing statements like this one, courtesy of the Memphis schools chief: “For those who say we need to get back to school, we say SCHOOL IS IN SESSION. Teachers are teaching their hearts out during live virtual instruction every day.”

Finally, given COVID-19’s disproportionate impact in minority communities amid searing debates about racial equity, there’s great incentive to avoid any action that could be portrayed as putting minority families at risk. Chicago Teachers Union official Stacy Davis Gates showed how this can work, critiquing the city’s reopening effort: “This makes no sense in a pandemic that continues to infect one in eight people in many of the Black and Brown Chicago neighborhoods that have already shouldered a disproportionate burden of COVID disease and death.” A teacher’s recent op-ed, complaining that parents who support reopening are disproportionately white, was headlined, “Are We Going to Let ‘Nice White Parents’ Kill Black and Brown Families?” No superintendent wants to risk being seen as an apologist for “white privilege,” fairly or no.

As if the asymmetries weren’t stark enough, the public narrative tends to emphasize the risks of reopening more than the costs of closure. While some teachers have complained during the pandemic that they’ve felt treated unfairly, the media has more typically depicted teachers as heroes at risk. One needn’t look further than Education Week’s “Educators We’ve Lost to the Coronavirus” tracker. The list, even though it’s heavily populated by retired educators, provokes a visceral sympathy. Nowhere is there a similar tally of the children lost to depression, abuse, and suicide due to closures.

In any political dispute, whether it concerns sugar subsidies or military base closures, decisions tend to favor organized interests and inertia tends to carry the day. Right now, that favors those who want schools closed. Changing this state of affairs requires more than impassioned pundits and a handful of frustrated parents (writes the pundit and parent). It requires changing the cost-benefit calculation for educational leaders. Parents and policymakers can do this by rewriting the narrative, or by altering the legal, financial, and professional stakes for public school officials.

Governors, who are better positioned than local school leaders to fully weigh the costs and benefits of closure, need to set clear expectations. Within hours of Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam saying last week that his state’s schools need to open in mid-March, districts that had spent five months dragging their heels suddenly announced that’s the plan. In Washington, Congress is on the verge of sending schools another $130 billion as part of Biden’s $1.9 trillion aid package. With these funds, Uncle Sam will have sent public schools an extra $200 billion this year, or triple what it typically provides. It’s time for Biden to flatly say, “Washington has done its part, public schools need to do theirs.” That kind of leadership can provide protective cover to fretful local school officials.

What else needs to be done? Public funds should be sent directly to families via vouchers or education savings accounts so that public schools can only pay expenses and salaries if families choose to enroll their students. (It’s no great surprise that private schools, which are dependent on attracting families, have been vastly more likely to remain open this year.) Some substantial portion of school aid should be conditioned on schools actually being open for in-person instruction. Parents should explore litigation charging unnecessarily shuttered districts with violating state constitutional provisions promising an adequate education. Frustrated parents need to organize and mobilize. Vulnerable kids need to be seen testifying before legislative committees and speaking on the steps of their shuttered schools.

Until the professional and political stakes change, the science will have a tough time carrying the day.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.